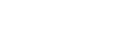

Graphical abstract. Factors that contribute to the unprecedented obesogenic environment during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a graphical abstract

Introduction

In December 2019, health authorities in the Hubei province of China identified a cluster of pneumonia cases of initially unknown etiology, linked to WuhanŌĆÖs South China Seafood Market [1]. Within days, an increasing number of patients presented to local hospitals with serious and, in some cases, fatal pneumonia, often including pyrexia, radiological signs of acute respiratory distress syndrome, lymphopenia, and failure to resolve infection over 3ŌĆō5 days of antibiotic treatment [1-3].

Subsequent investigations identified a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus [2], as the causative agent that originated in bats and was transmitted to humans through yet unknown intermediary animals in the Chinese city of Wuhan [1,4]. The number of deaths rose quickly, and on January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization officially declared the coronavirus epidemic a public health emergency of international concern [2,5]. The local Wuhan and national Chinese governments took unprecedented measures in response to this outbreak [6-8]. Schools remained closed and holidays were extended to allow people to stay away from their workplaces. Moreover, the local government promoted physical distancing, community containment, and the avoidance of crowded places [7,9]. The Chinese government additionally discouraged public activities to prevent the infectionŌĆÖs spread [10].

Public transportation, including trains and buses, within Wuhan was restricted and other prevention and control measures, such as isolation and quarantine, were gradually established in the city [9,11]. Wuhan, a key transport hub located 4 hours from Beijing by train, was shut down and its 11 million citizens were quarantined [1].

Quarantine

Quarantine is defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the separation and restriction of the movement of people who have been exposed to a contagious disease to ascertain if they become unwell [12], so as to reduce the risk of them infecting others [13]. Quarantine is considered an effective control measure when a disease is likely to result in a large number of secondary cases despite the isolation of symptomatic individuals [14,15]. On the other hand, quarantine is also frequently an unpleasant experience for those who undergo it [13]. The loss of freedom and control, a sense of being trapped, and ultimately the separation from loved ones may have dramatic effects [13,16]. including significant psychological and psychiatric disturbances [17]. Finally, quarantine may have long-term psychological effects that can prevail for months or years [18,19]. Regardless, the potential benefits of mandatory mass quarantine must be weighed carefully against its possible psychological costs [13,16]. Therefore, considering the significant secondary and tertiary effects introduced by quarantine is of paramount importance [20]. Specifically, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic will substantially impact another already threatening pandemic affecting most parts of the Western world and many developing countries: the childhood obesity epidemic.

Childhood obesity

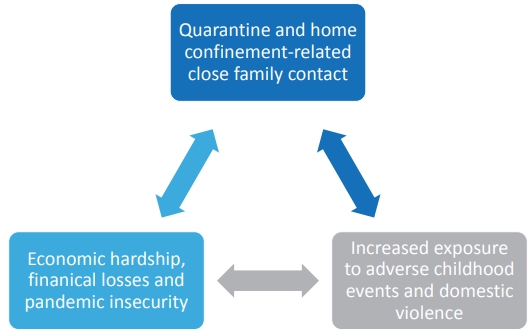

Obesity is a global public health challenge [21] whose incidence has increased worldwide over the past five decades [22], reaching pandemic levels [23]. Worldwide, more than 600 million people are obese and another 2 billion are overweight [22]. Children are at special risk of carrying excess weight, the prevalence of which has increased dramatically in recent decades [24-26]. Furthermore, obese children are likely to become obese adults [24,26,27]. Therefore, controlling the obesity epidemic has become a top priority for public health authorities, and community-based approaches are a cornerstone of many health interventions [28]. The current COVID-19 pandemic, however, may significantly impede the implementation of such interventions and constitute an unprecedented tragedy in the global battle against obesity. School closures and subsequent home confinement measures may negatively affect childrenŌĆÖs physical and mental health [10]. The COVID-19 pandemic will aggravate the epidemic of childhood obesity and lead to significant weight gain in school children by creating an unprecedented obesogenic environment. Psychosocial factors are the driving force behind this concern.

Unprecedented obesogenic environment

Quarantine and other types of traditional outbreak responses have been successfully employed in the past; however, they have never been executed on such a large scale [9]. School closures currently impact over 91% of the global student population [29]. Rundle et al. [30] anticipated that the COVID-19 pandemic could double out-of-school time for many children in the United States in 2020. Children are literally forced to stay at home and are now exposed to a different environment than usual.

This exceptional situation may carry a series of negative effects that warrant further investigation. Several studies suggested that when children are out of school, during the summer months for example, they are less physically active and experience unhealthy weight gain [10,30-32]. Moreover, children lose access to almost all forms of supervised sources of physical activity as a result of school closures [33]. Contrary to public opinion, results from an American longitudinal study suggested that the risk of obesity is higher when children are out of, rather than in, school [34].

Such weight gain in childhood is of long-term concern [30] since studies have shown that obesity that develops at early age (age 5 years) is associated with both significantly higher fat mass and a higher body mass index (BMI) at age 50 years [35]. In one study, Rundle et al. [35] emphasized that participants who were obese at 5 years of age had BMI scores at 50 years of age that were 6.51 units higher (95% confidence interval,3.67ŌĆō9.35) than those with a normal weight at 5 years of age.

According to Brazendale et al. [31], obesogenic behaviors such as sedentary behavior, increased screen time, a poor diet, and irregular sleep are beneficially regulated when children follow a structured day. Although some governments have rapidly implemented emergency home schooling plans [10], it is difficult to establish a clear structure for children during these unprecedented times. This may result in irregular sleep patterns and extensively prolonged screen times due to online class and lecture offerings (in addition to leisure screen time), leading to weight gain and reduced cardiorespiratory fitness levels [10]. Dunton et al. [36] recently raised the concern that the current negative short-term changes in sedentary behavior and physical activity may become permanently entrenched in children. Significantly increased screen time in particular may contribute to overweight and obesity in affected children [37-39]. According to Fang et al. [37], a screen time of Ōēź2 hours per day significantly increased the risk of overweight and obesity among children compared to a screen time of <2 hours per day. Current evidence suggests that increased screen media exposure leads to obesity in children in several ways, including increased eating while viewing [38].

It is reasonable to assume that children are exposed to less favorable diets during quarantine [40]. Given movement restrictions, people have limited access to fresh and unprocessed foods [41]. Instead, many rely on nonperishable and highly processed food options that contribute to food security [42]. However, these highly processed foods tend to be high in saturated fat, sugar, and salt [41,43]. Several large investigations have associated the consumption of such foods with adverse health outcomes, including obesity and metabolic syndrome [44-47]. A recently published Italian study found that the intakes of potato chips, red meat, and sugary drinks increased significantly during the lockdown [48]. Another recently published international investigation reported similar findings [49]. In contrast, one study also noted a positive trend: the extent to which parents supervise their childŌĆÖs eating increased as well [50].

Furthermore, quarantine may also have a negative psychological impact on children and their families [10,51-53]. A variety of unfamiliar stressors disrupt childrenŌĆÖs usual lifestyle, including a lack of in-person contact with classmates, friends, and teachers, feelings such as frustration and boredom, and a possible lack of personal space at home [10,13,32]. In this context, a 2013 study demonstrated that pandemic disasters and subsequent disease containment responses create traumatic conditions [54]. Such an unfamiliar and likely prolonged stressful situation could further promote unhealthy food intake through stress-related eating, thereby leading to obesity and other health problems [55,56]. Although studies of children are scarce in this particular field, one study showed that stress-related eating is highly prevalent among 16-year-old girls [57] and could be exacerbated by the current pandemic.

Many families are expected to experience financial losses or even existential threats as a consequence of the pandemic [10,58]. This might affect children in many ways; however, 2 specific aspects warrant further investigation. First, families experiencing reduced income and financial losses will encounter difficulty affording fresh and unprocessed whole foods. According to Headey and Alderman [59], low incomes constrain what and how much food poor households can buy. Parents on a tight budget might not be able to afford fresh and healthy plant-based food options; instead, their often dramatically reduced budgets will force them to feed their children calorie-dense processed foods that are often cheaper [59,60]. This, in turn, might increase the risk of obesity and other metabolic disorders as previously explained [45,47]. Second, families will have to cope emotionally with potential economic or job losses. The COVID-19 pandemic has already led to major increases in unemployment and job insecurity rates [61,62]. Family members spend more time in close contact and, according to the World Health Organization, the current crisis will likely lead to an increase in domestic violence [63,64]. Reports from several countries, including China, Germany, Italy, and Brazil, have indicated an increase in domestic violence since the COVID-19 outbreak began [63,65]. Women in abusive relationships and their children are at particularly high risk [66]. Regarding childhood obesity, the predicted increase in child abuse is the most worrisome.

Several years ago, an American study demonstrated that adverse childhood events (childhood sexual abuse) are associated with obesity and eating disorders [67]. Moreover, a 2013 meta-analysis by Danese and Tan [68] including 41 studies and more than 190000 participants revealed that childhood maltreatment was associated with an elevated risk of developing obesity over the lifespan (odds ratio, 1.36; 95% confidence interval, 1.26ŌĆō1.47). Ultimately, Hemmingsson et al. [69] found that adverse life experiences during childhood potentially contribute to obesity by inducing mental and emotional perturbations, maladaptive coping responses, metabolic disturbances, and stress. Fig. 1 displays the close interrelation between quarantine, pandemic-related economic hardship, and the increased risk of domestic violence.

Finally, the COVID-19 response measures, including social distancing, self-isolation, and community lockdowns, may severely limit access to health care services and preventive care in the primary care setting [70]. In many countries, social work staff have to self-isolate, which strains service delivery and stretches safeguarding teams [71]. This factor may not be underestimated in the battle against domestic violence and adverse childhood events.

Table 1 briefly summarizes the factors that contribute to the unprecedented obesogenic environment children face during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

During major infectious disease outbreaks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, quarantine can be a necessary preventive tool for infection control. This manuscript, including evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic will aggravate the childhood obesity epidemic, does not suggest that quarantine should not be used, as the psychological effects of not using quarantine and allowing the disease to spread further might be worse [13,74]. However, this manuscript presents several convincing arguments that the COVID-19 pandemic will aggravate the epidemic of childhood obesity by creating an unprecedented obesogenic environment.

While obesity has always been a problem in pandemic situations (for example, during the influenza A [H1N1] virus pandemic in 2009 and 2010), studies traditionally focused on obesity as a risk factor for an aggravated clinical course [75,76]. In contrast, studies pointing at quarantine during infectious disease pandemics as a risk factor for childhood obesity itself are scarce. On the contrary, some arguments presented in this review remain speculative.

Moreover, nobody can predict how long quarantine statuses will be maintained. Shorter quarantine periods may have only a modest effect on the physical and mental health of children compared to longer periods. However, nobody can reliably predict how long the COVID-19 pandemic will last. Thus, shorter quarantine periods might weaken the statements presented in this paper, whereas long-lasting infective control measures might strengthen them.

Finally, different countries worldwide manage the COVID-19 pandemic in different ways. There are various strategies for managing school closures and home confinement-related issues. Countries commanding large amounts of resources and an effective administrative system might be able to quickly establish emergency strategies and sustainable programs to reduce the physical and mental impact of the COVID-19 epidemic in children. In turn, this might counteract the creation of an unprecedented obesogenic environment for children.

Conclusion

This manuscript presented evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic will aggravate the childhood obesity epidemic and lead to significant weight gain in school children by creating an unprecedented obesogenic environment. It also described the physical, nutritional, and psychosocial factors that could promote obesity in children during this special situation.

The psychosocial aspects of quarantine, including new and unfamiliar stressors for children, will be the driving force that may worsen the childhood obesity epidemic. These factors include a lack of in-person contact with classmates, friends, and teachers; feelings such as frustration and boredom; and a potential lack of personal space at home. It is likely that adverse childhood events resulting from a significant increase in domestic violence within the next few months will significantly contribute to childhood obesity and eating disorders in the near future.

Physical, nutritional, and psychosocial aspects might complementarily contribute to the creation of an unprecedented obesogenic environment. Although some of the arguments in this manuscript are speculative, an increase in childhood obesity rates during the COVID-19 pandemic is a realistic scenario. One thing is for sure: children have limited ability to advocate for their needs and might suffer the most from the current pandemic.

Only the future will reveal the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic will affect childhood obesity. Nevertheless, pandemic planning must address this concerning scenario now, and involved stakeholders (including governments, schools, and families) must make all possible efforts to minimize the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on childhood obesity.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation