Effectiveness and safety of seasonal influenza vaccination in children with underlying respiratory diseases and allergy

Article information

Abstract

Influenza causes acute respiratory infections and various complications. Children in the high-risk group have higher complication and hospitalization rates than high-risk elderly individuals. Influenza prevention in children is important, as they can be a source infection spread in their communities. Influenza vaccination is strongly recommended for high-risk children with chronic underlying circulatory and respiratory disease, immature infants, and children receiving long-term immunosuppressant treatment or aspirin. However, vaccination rates in these children are low because of concerns regarding the exacerbation of underlying diseases and vaccine efficacy. To address these concerns, many clinical studies on children with underlying respiratory diseases have been conducted since the 1970s. Most of these reported no differences in immunogenicity or adverse reactions between healthy children and those with underlying respiratory diseases and no adverse effects of the influenza vaccine on the disease course. Further to these studies, the inactivated split-virus influenza vaccine is recommended for children with underlying respiratory disease, in many countries. However, the live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) is not recommended for children younger than 5 years with asthma or recurrent wheezing. Influenza vaccination is contraindicated in patients with severe allergies to egg, chicken, or feathers, because egg-cultivated influenza vaccines may contain ovalbumin. There has been no recent report of serious adverse events after influenza vaccination in children with egg allergy. However, many experts recommend the trivalent influenza vaccine for patients with severe egg allergy, with close observation for 30 minutes after vaccination. LAIV is still not recommended for patients with asthma or egg allergy.

Characteristics and effects of influenza infection in children

Influenza frequently results in the development of acute respiratory infection in children younger than 2 years, with a higher admission rate than that caused by respiratory syncytial virus infection1). During an influenza epidemic, influenza-related morbidity increases significantly in children younger than 1 year, with the ratio of emergency department visits increasing to 237/100,0002) and an influenza-associated hospitalization rate of 120/100,0003). High admission rates have been reported for children younger than 1 year with underlying circulatory or respiratory disease. During an influenza epidemic, the influenza infection attack rate is approximately 40% and 30% in preschool children and school children, respectively, implying high infectivity4,5).

Clinically, influenza causes acute respiratory infections such as croup, bronchitis, and primary and viral pneumonitis. Consequently, it may lead to complications such as secondary bacterial otitis media, pneumonia, myositis, encephalitis, myocarditis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and Reye's syndrome, and multiorgan failure may develop6,7,8). These serious complications are not rare5,9). The rates of complication development and admission can be higher in children in the high-risk group than in the high-risk elderly population. In addition, infected children can be a source of infection spread in their family10,11,12,13). Therefore, preventing influenza infection in children is very important.

The importance of vaccination in the control of influenza infection

Prevention of influenza by vaccination is the most effective means of decreasing the socioeconomic burden of influenza14). Trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines containing two influenza A and one influenza B subtype are usually employed. The antigen type to be included in the vaccine is reviewed by the World Health Organization (WHO) annually, and this varies to match the strains most prevalent in the hemisphere. In general, available influenza vaccines limit disease severity and reduce serious complications associated with influenza infections. Clinically, the protective value of influenza vaccines is related to their immunogenicity. Additionally, there is a clear link between immunogenicity and vaccine effectiveness; however, it is difficult to accurately quantify this link due to several factors that cannot be accurately quantified. These factors include herd immunity due to high vaccination rates and mismatched types in circulation or resistance to recurring strains after considerable periods. Furthermore, the efficacy of influenza vaccines may be influenced by various factors including age, prior vaccination, prevaccination antibody titers, immune status of the vaccinee, and the concurrent use of drugs such as steroids or immunosuppressive agents15). However, influenza vaccination decreases influenza morbidity and mortality and reduces societal costs. Cost-effectiveness has also been confirmed in various studies on high-risk infants and children16,17,18). Vaccination is useful in preventing influenza in approximately 31%-91% of healthy children and children with asthma. In particular, vaccination significantly prevents hospitalization due to influenza-related complications.

General recommendations for the use of influenza vaccines in children

As described, children with influenza can be a source of disease spread in the community. Therefore, influenza vaccination is very important; if the vaccine is in short supply, children should be given priority. When vaccination was conducted proactively for children, influenza infection and death rates decreased in adults6,19,20,21). In particular, intensive vaccination of school children and infants aged 6-23 months is essential.

The modern influenza split vaccine was developed by the Pasteur Company in 1969, and the use of split or subunit influenza vaccines was widespread in the 1970s. Since 1981, each 0.5 mL of influenza vaccine is mixed with 15 µg of hemagglutinin antigen for use as the trivalent inactivated split vaccine (two types of A antigens and one type of B antigen)16,22).

For infants aged 6-35 months, a 0.25-mL dose of influenza vaccine should be administered. Children aged 6 months to 8 years, who are receiving the influenza vaccine for the first time require two doses, administered at an interval of more than 4 weeks; only a single dose is needed from the second year of vaccination23,24). The prefilled influenza vaccine was introduced in 1995, and the live-attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV) was developed for use in healthy children aged 2 years or older. However, the recombinant influenza vaccine and cell culture-based vaccine, which were developed later, have not yet been used in children.

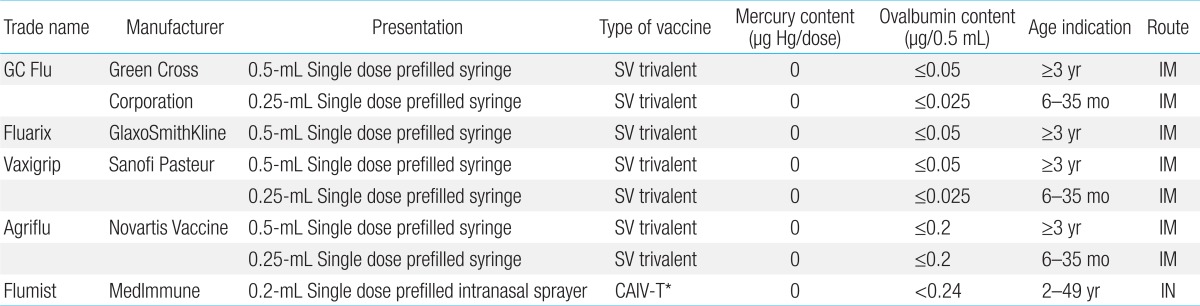

The WHO strongly recommends influenza vaccination for young children, and since 2011, vaccination has been recommended for all individuals older than 6 months. In 2012, the B antigen was mixed with one type of Victoria lineage antigen and one type of Yamagata lineage antigen as a quadrivalent influenza vaccine; this new formula has been used since 2013. Because of a 2-4 times higher risk of influenza infection, hospital admission, and the development of complications compared with healthy children, vaccination is strongly recommended for high-risk children with cancer, chronic circulatory or respiratory disease, or human immunodeficiency virus infection; immature infants; and children receiving long-term treatment with immunosuppressive agents or aspirin24). As a cocooning strategy, vaccination is recommended not only for these high-risk children but also for individuals who cannot avoid physical contact. To reduce the risk of infection, vaccination is strongly recommended for mothers of infants younger than 6 months25). Vaccination is also recommended for children in other high-risk groups, including children younger than 2 years, children in daycare centers, and children aged 5-17 with chronic diseases. In South Korea, elderly people aged 65 years or older are vaccinated as part of the national immunization program. This vaccine is also strongly recommended for children aged 6 months or older. Nevertheless, no detailed recommendations for children in the high-risk group with underlying diseases have been proposed yet, particularly in the case of children with underlying respiratory diseases or allergies such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), asthma, or egg allergy. Currently, five types of influenza vaccines are used in children (Table 1) in Korea.

Studies of the safety and efficacy of inactivated influenza vaccines in children with underlying respiratory diseases

Severe influenza infection is observed in all children; however, vaccination is essential for children with chronic respiratory disease, heart disease, and cancer, and for children receiving long-term immunosuppressant therapy. This is because of the risk for serious complications. More specifically, children with chronic respiratory diseases, including BPD and asthma, can experience deterioration of pulmonary function or have other complications after influenza infection, increasing the admission rate26,27,28). Therefore, vaccination is strongly recommended for these children as well29). Nevertheless, the actual vaccination rate is low because of concerns that the influenza vaccination exacerbates asthma and questions regarding its efficacy in patients receiving steroid treatment30). To help resolve these problems, many clinical studies have been conducted since the 1970s (Table 2).

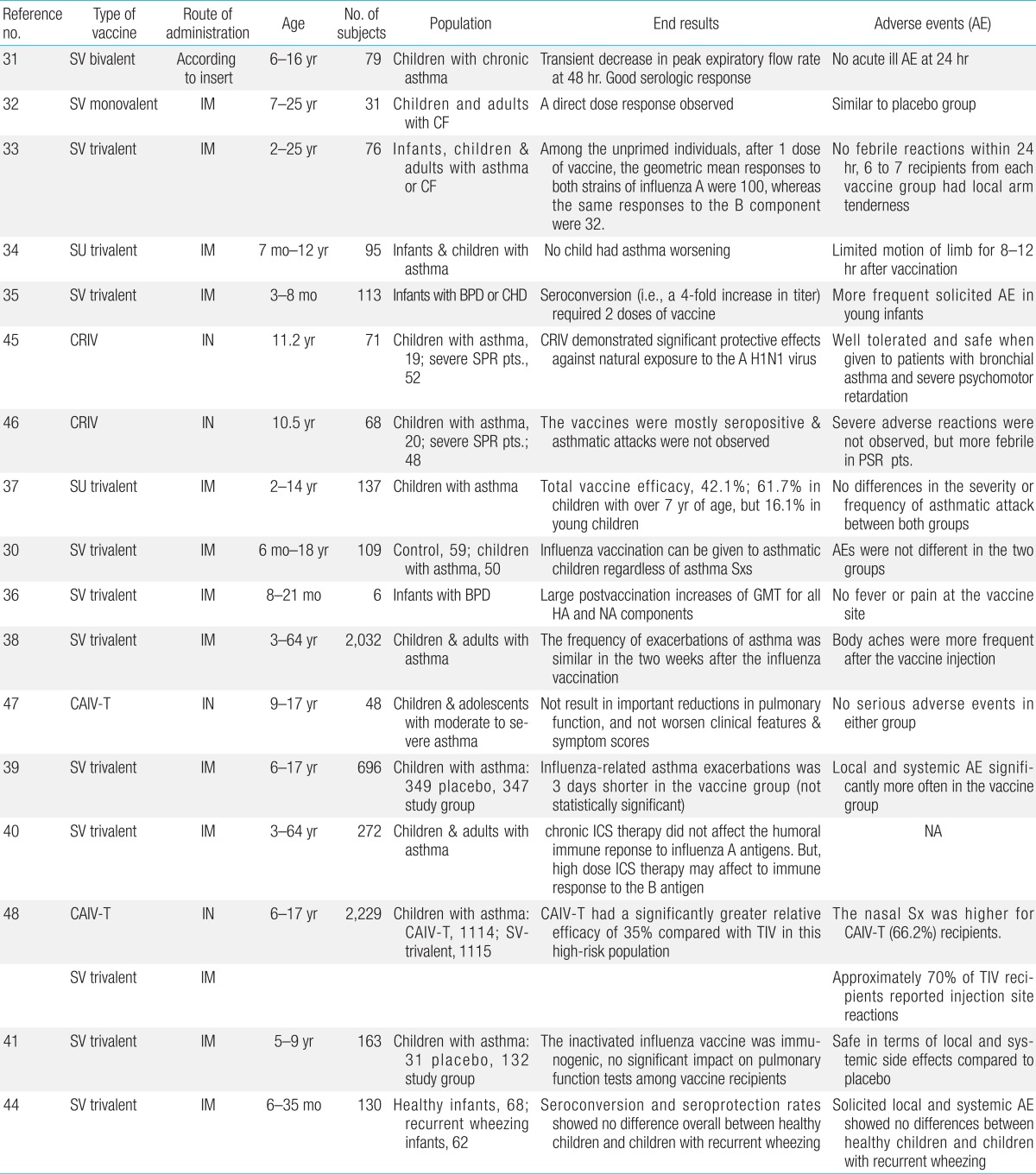

Characteristics and end results of clinical studies involving children with asthma and underlying respiratory diseases that evaluated efficacy and safety of seasonal influenza vaccines (inactivated or live attenuated)

In 1978, Bell et al.31) conducted the first study of the bivalent split influenza vaccine in 6- to 16-year-old children with chronic asthma. The authors found no differences in immunogenicity compared to healthy children, and no adverse reactions were observed within 24 hours. Forty-eight hours after vaccination, several children showed a temporary decrease in the peak expiratory flow rate and required the use of a bronchodilator. According to a study on 31 unprimed children and young adults with cystic fibrosis conducted by Gross et al.32) in 1980, a direct response was observed in a group of children who received the influenza vaccine, and there was no difference in adverse events compared to the placebo group. In another study on two types of the trivalent split influenza vaccine including 76 children and young adults with asthma or cystic fibrosis conducted in 1981, the same authors reported higher immune reactions against the A antigen than against the B antigen33). In 1991, Ghirga et al.34) conducted a study on the trivalent subunit influenza vaccine, which included 95 infants and children with moderate to severe asthma and reported that subjects showed no deterioration in asthma after vaccination, although three subjects experienced a temporary limitation in limb movements, without systemic reactions. In 1991, Groothuis et al.35) reported that, in 113 children with BPD or congenital heart disease aged 3-18 months, mild adverse reactions were reported in 6%-14% of cases, and two-dose vaccination was required in order to achieve four-fold seroconversion. In a 1998 clinical report, Brydak et al.36) reported that six infants with BPD aged 8-21 months who received two doses of 0.25 mL of the trivalent split influenza vaccine showed a high-fold increase in geometric mean titers. Since 1990, numerous studies on split or subunit influenza vaccines for children with asthma showed no difference in immunogenicity against A antigens between asthma patients and healthy children, whereas in the case of B antigens, asthma patients had slightly lower immunogenicity than healthy children37). In addition, some studies reported a temporary deterioration in asthma; however, most studies reported no adverse effect of the influenza vaccine on the course of asthma and no significant difference in adverse reactions between children with asthma and healthy children30,38,39,40,41,42,43). Considering these results, although short-term corticosteroid or alternative therapies affect antibody formation to a small extent, these treatments may not interfere with the influenza vaccine. However, in the case of high-dose administration at 2 mg/kg or 20 mg/day, a delay in vaccination is recommended6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21). However, vaccination guidelines for patients with persistent asthma who use inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) on a long-term basis have not yet been clearly established. According to a study of children and adults with persistent asthma conducted by Hanania et al.40) in 2004, antibody reactions against A antigens (H1N1, H3N2) were not affected in chronic ICS users; however, reactions against B antigens may be sluggish in high-dose ICS users. This outcome corresponded with those of previous studies. In association with directly linked B-cell function, the influenza vaccine usually shows antibody reactions; however, with decreased function of T helper cells, antibody reactions also declined43). Accordingly, these outcomes provide chronic ICS users with a basis for the recommendation of influenza vaccination. According to a recent study by Bae et al.44), infants with recurrent wheezing, even those who received steroids for a short period of time, developed immunogenicity against A and B antigens after influenza vaccination. In studies since the mid-1990s on cold-adapted live attenuated influenza vaccine targeting asthma patients aged 5 years or older45,46,47,48,49), immunogenicity was achieved without difficulty, and the level was even higher than that achieved with the inactivated split influenza vaccine, without adverse reactions other than nasal symptoms. Considering these outcomes, inactivated split-virus influenza vaccination is recommended for children with underlying respiratory diseases, including asthma, in many countries. However, LAIV is still not recommended for children younger than 5 years of age with asthma and recurrent wheezing49).

Guidelines for the use of influenza vaccines in children with egg allergy

Influenza vaccination is contraindicated in patients severely allergic to egg, chicken, or feathers, because ovalbumin may remain in egg-cultivated influenza vaccines. In previous studies, direct skin tests with the influenza vaccine or whole eggs were suggested for determining the feasibility of vaccination50,51,52). According to a study on 142 allergic children conducted by Bierman et al., an intradermal skin test using a 1:100 mixture of the influenza vaccine and normal saline was more objective in determining the feasibility of influenza vaccination than a history of egg allergy52).

In recent studies on trivalent influenza vaccination in children with a history of egg allergy53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60), no serious adverse reactions such as respiratory distress, hypotension, or shock were reported; however, minor adverse reactions such as hives and mild wheezing were reported, indicating that development of serious systemic adverse reactions is rare with trivalent influenza vaccination. Even in patients with severe allergic responses to egg ingestion, no serious adverse reactions were observed, and there were no differences in adverse reactions between patients with positive and negative skin test results. Accordingly, these skin tests were reported to be unnecessary for patients with egg allergy54,55,57,59,60). In addition, a study comparing a divided dose and single dose found no difference in adverse reactions56,57,59,60). The amount of ovalbumin present is usually less than 1 µg per 0.5 mL-dose, and the products currently in use have a lower amount of ovalbumin; thus, a severe adverse reaction may not occur, even in patients with serious egg allergy61,62). A small amount of ovalbumin is present in LAIV; however, the use of LAIV in patients with egg allergy has not been studied. Therefore, LAIV administration is not recommended for patients with egg allergy. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) in America recommends the trivalent influenza vaccine for patients with serious egg allergies, with close observation for 30 minutes after vaccination; however, the use of LAIV in patients with asthma or egg allergy is contraindicated63). In addition, the ACIP recommends that patients with circulatory symptoms such as hypotension and shock,; respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, or digestive symptoms such as severe nausea and vomiting and patients requiring epinephrine or emergency medical attention after ingesting eggs or egg foods consult with professionals prior to receiving vaccination64).

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.