Intravenous levetiracetam versus phenobarbital in children with status epilepticus or acute repetitive seizures

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study compared the efficacy and tolerability of intravenous (i.v.) phenobarbital (PHB) and i.v. levetiracetam (LEV) in children with status epilepticus (SE) or acute repetitive seizure (ARS).

Methods

The medical records of children (age range, 1 month to 15 years) treated with i.v. PHB or LEV for SE or ARS at our single tertiary center were retrospectively reviewed. Seizure termination was defined as seizure cessation within 30 minutes of infusion completion and no recurrence within 24 hours. Information on the demographic variables, electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging findings, previous antiepileptic medications, and adverse events after drug infusion was obtained.

Results

The records of 88 patients with SE or ARS (median age, 18 months; 50 treated with PHB and 38 with LEV) were reviewed. The median initial dose of i.v. PHB was 20 mg/kg (range, 10–20 mg/kg) and that of i.v. LEV was 30 mg/kg (range, 20–30 mg/kg). Seizure termination occurred in 57.9% of patients treated with i.v. LEV (22 of 38) and 74.0% treated with i.v. PHB (37 of 50) (P=0.111). The factor associated with seizure termination was the type of event (SE vs. ARS) in each group. Adverse effects were reported in 13.2% of patients treated with i.v. LEV (5 of 38; n=4, aggressive behavior and n=1, vomiting), and 28.0% of patients treated with i.v. PHB (14 of 50).

Conclusion

Intravenous LEV was efficacious and safe in children with ARS or SE. Further evaluation is needed to determine the most effective and best-tolerated loading dose of i.v. LEV.

Introduction

Status epilepticus (SE) and acute repetitive seizure (ARS) are the most common life-threatening neurological emergencies, and have high morbidity and mortality. Acute management of seizure is important to prevent irreversible neuronal damage. The ideal antiepileptic drug for acute seizure control should act rapidly, be delivered easily by intravenous (i.v.) formulation, and have a sustained duration without adverse effect. Among the widely accepted recommendation of treatment of SE and ARS, benzodiazepines, including lorazepam and diazepam are the first-line therapy123). If first-line therapy fails to control the seizure, phenobarbital (PHB) and phenytoin are commonly used as the second-line antiepileptic drug. However, the current treatment protocol in children is not evidence-based and these antiepileptic drugs have well known adverse effects including respiratory suppression, hypotension, deep sedation, and multiple complications in various organs. Therefore, new antiepileptic drugs that can stop seizures without serious adverse effects are needed.

Other antiepileptic drugs such as valproic acid, levetiracetam (LEV), and lacosamide have been introduced for the treatment of SE and ARS, but no randomized controlled trial has directly compared the efficacy of these antiepileptic drugs. Intravenous LEV has been suggested as an effective and safe treatment for acute seizure control in adult patients with SE or ARS4567), and has recently been approved as an adjuvant antiepileptic drug in patients aged 16 years and older when oral therapy is not tolerated. LEV has a different mechanism to preexisting antiepileptic drugs. It binds to synaptic vesicle protein SV2A and modulates synaptic vesicle exocytosis and neurotransmitter release. It also has fewer severe adverse effects such as respiratory depression and hemodynamic instability89). Furthermore, neuroprotective effects have been reported in animal models10). Intravenous LEV has rapid onset, minimal plasma protein binding (<10%), 100% bioavailability, and low drug-drug interaction with linear pharmacokinetics. The pharmacokinetic profile is consistent with that of oral LEV in adults9). Because of these favorable characteristics, i.v. LEV is useful in situations that require rapid administration, including traumatic injury, neurosurgery, and when undergoing chemotherapy. Despite increased use of i.v. LEV, there was no controlled study to compare the efficacy of i.v. LEV and i.v. PHB in pediatric patients with SE or ARS. The purpose of this study was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of i.v. LEV and i.v. PHB in children with benzodiazepine-refractory SE or ARS.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of children (aged 1 month to 15 years) who were treated with i.v. PHB or i.v. LEV for benzodiazepine-refractory SE or ARS at the Asan Medical Center, a single tertiary center in Korea. This study was approved by the Asan Medical Center's Institutional Review Board. We identified patients treated with i.v. PHB between April 2008 and March 2010, and patients treated with i.v. LEV between April 2010 and December 2013, after the introduction of i.v. LEV in our hospital. After the introduction of i.v. LEV at 2010, i.v. PHB and i.v. LEV were randomly given to the patients with ARS or SE. The loading dose of i.v. PHB was 10–20 mg/kg and that of i.v. LEV was 20–30 mg/kg. The loading dose of i.v. LEV was administered over 15 minutes and was followed by a maintenance dose of 10–15 mg/kg every 12 hours. Patients were excluded from analysis if they required immediate neurosurgery, or if they were alleged patients with refractory epilepsy who were treated with more than two antiepileptic drugs. SE was defined as continuous seizure activity for more than 5 minutes or recurrent seizures without recovery of consciousness within 30 minutes11). ARS was defined as seizures lasting less than 5 minutes within 30 minutes and occurring more than 2 times with recovery of consciousness between each seizure12). Termination of seizures was defined as clinical seizure cessation within 30 minutes of completion of the infusion without recurrence during the following 24 hours12).

We collected information by medical records including patients demographic data, the underlying neurologic disorder, seizure type, previous antiepileptic drug medication, provocation factors of SE or ARS. We also collected loading dose of each medication, success or failure of seizure termination and adverse events of the antiepileptic drugs. Seizure types and epilepsy syndromes were classified in accordance with the International League Against Epilepsy classification and revised concept and terminology of seizure and epilepsy13).

Efficacy was evaluated using seizure termination rate and tolerability was evaluated using acute adverse events after drug infusion. Efficacy and tolerability were compared between the two groups (i.v. PHB and i.v. LEV) using a Fisher exact test or Student t test. Baseline demographic and clinical categorical variables were compared between the 2 groups using Fisher exact test (categorical variables) or Student t test (continuous variables). PASW Statistics ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analysis. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

1. Patient characteristics

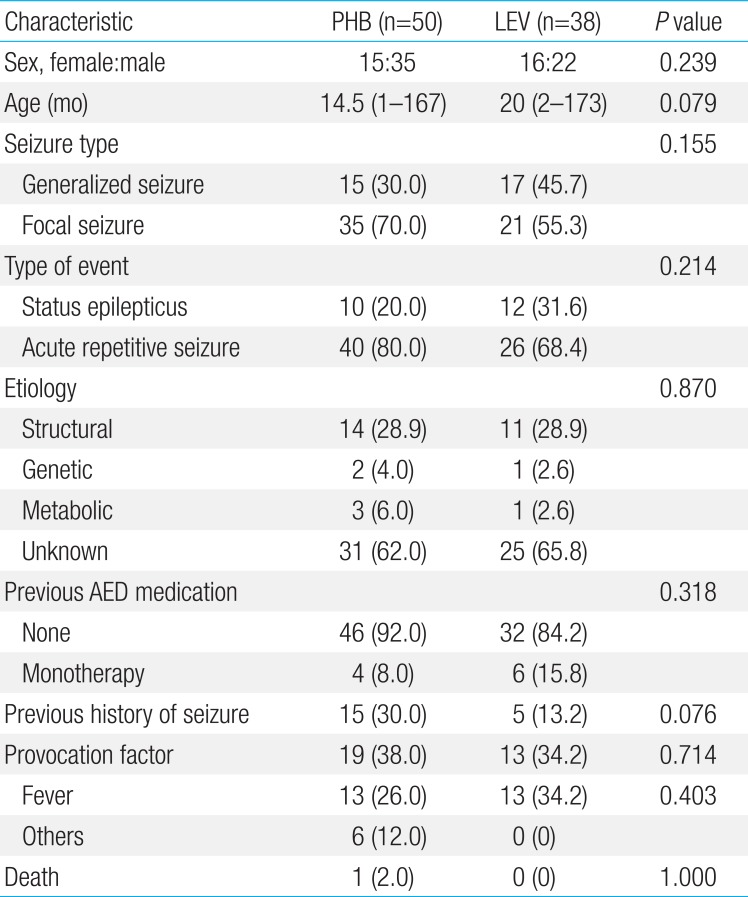

A total of 88 patients were identified who had been treated with i.v. PHB or i.v. LEV for SE or ARS (Table 1). Fifty patients had received i.v. PHB and 38 patients had received i.v. LEV. The PHB group included 15 females and 35 males, with a median age of 14.5 months (range, 1 month to 13.9 years). The LEV group included 16 females and 22 males, with a median age of 20 months (range, 2 months to 14.4 years). In both groups, the most common provocation factor of seizure was fever (n=26) followed by acute gastroenteritis (n=4), concussion (n=1), and hypoglycemia (n=1). We compared patient characteristics between the PHB group and the LEV group. Age, sex, seizure type, type of event, etiology, previous history of seizure, previous antiepileptic drug medication, presence or absence of the provocation factors, fever, and mortality were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1) showing the even distribution of patients in each group.

2. Efficacy of i.v. PHB and i.v. LEV

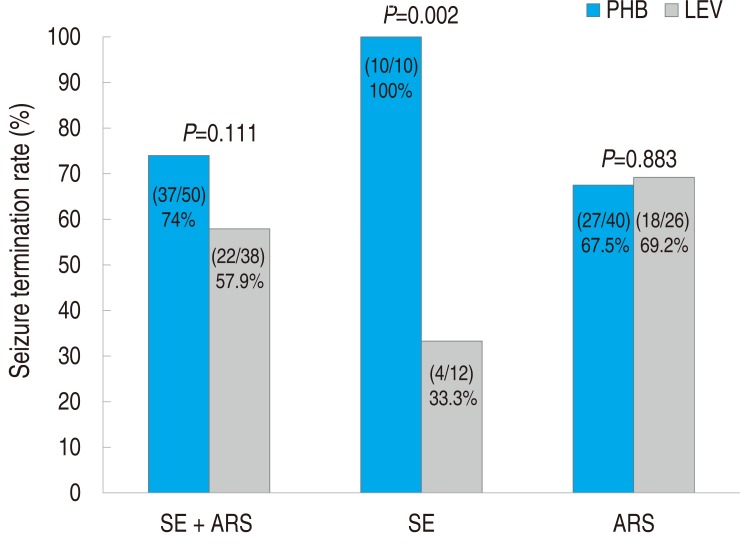

In the PHB group, 37 of 50 patients (74%) experienced seizure termination (i.e., seizures were controlled by 30 minutes after i.v. infusion of the loading dose and did not recur within 24 hours). In the LEV group, 22 of 38 patients (57.9%) experienced seizure termination. The overall seizure termination rate did not significantly differ between the two groups (P=0.111) (Fig. 1). However, among patients treated for SE, seizure termination rate was much higher in the PHB group than in the LEV group. In the PHB group, all ten patients with SE (100%) experienced seizure termination. By contrast, in the LEV group, only 4 of 12 patients (33.3%) with SE experienced seizure termination (P=0.002). Seizure termination rate in patients with ARS was not significantly different between the two groups (P=0.883).

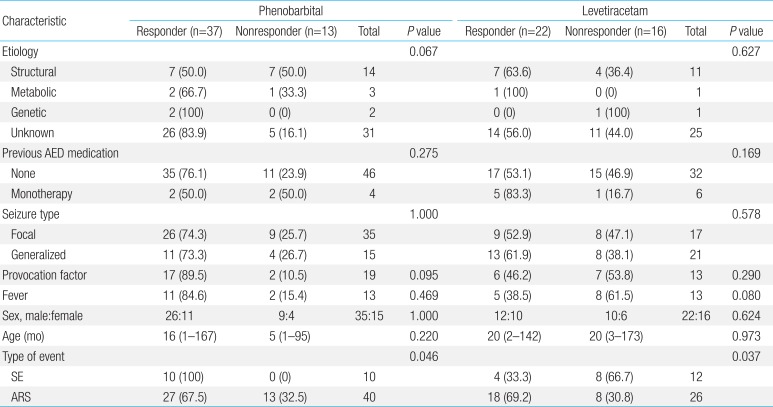

3. Comparison of responders and nonresponders in each group

Baseline characteristics were compared between responders and nonresponders to i.v. LEV and i.v. PHB, respectively (Table 2). In both groups, age, sex, seizure type, etiology, previous antiepileptic drug medication, presence of provocation factors were not significantly different between responders and nonresponders. The type of event (SE vs. ARS) did significantly differ between responders and nonresponders in both the LEV group and the PHB group. Efficacy of i.v. LEV was much higher in patients with ARS than in patients with SE (seizure termination rate: 69.2% [18 of 26] vs. 33.3% [4 of 12], P=0.037), while that of i.v. PHB was much higher in patients with SE than in patients with ARS (seizure termination rate: 67.5% [27 of 40] vs. 100% [10 of 10], P=0.046).

4. Tolerability of i.v. PHB and i.v. LEV

Adverse events were observed in 14 of 50 patients (28%) in the PHB group and 5 of 38 patients (13.2%) in the LEV group. The overall occurrence of adverse events was not significantly different between the 2 groups (P=0.094) (Table 3). Three patients discontinued PHB due to rash (n=1) or behavior change (n=2). Three patients discontinued LEV because of irritability or recurrent vomiting, but no patient experienced deep sedation or rash after i.v. LEV infusion. No patients in either group presented severe adverse events such as hypotension, cardiac arrhythmia, respiratory depression, or death.

Discussion

Our results show that i.v. LEV was as effective as i.v. PHB for the treatment of ARS in pediatric patients and did not result in any serious side effects. In recent years, the efficacy of i.v. LEV for SE has been shown in adult patients 4567). Eue et al.4) reported that refractory SE was controlled by i.v. LEV in 19 of 43 patients (44.2 %) without adverse effect. In another study, i.v. LEV was effective in 57.5% of 40 adult patients as an add-on treatment for SE5). However, there are limited data on the efficacy of i.v. LEV for SE and ARS in children12141516171819). McTague et al.12) reported that i.v. LEV terminated seizures in 23 of 39 children (59%) with ARS, 3 of 4 children (75%) with convulsive SE, and two children with non-convulsive SE. Kim et al.17) reported a seizure termination rate of 43% in 14 pediatric patients who received i.v. LEV for refractory SE. Isguder et al.18) reported a seizure termination rate of 78.2% in 133 children with ARS after i.v. LEV infusion. However, the retrospective design of these studies combined with the small number of patients, the variable definition of seizure termination, and the variable loading dose of i.v. LEV limits the conclusions that can be drawn regarding the efficacy of i.v. LEV for ARS or SE in children.

Thus, we tried to compare the efficacy of LEV in ARS or SE to that of PHB, which was used as the standardized second line therapy in ARS or SE. A recent meta-analysis in adults with benzodiazepine-refractory SE evaluated the efficacy of five antiepileptic drug (phenytoin, phenobaribtal, valproic acid, LEV, and lacosamide)20) and shows a similar efficacy of LEV (mean efficacy of 69%) compared to that of PHB (mean efficacy of 74%) and a low risk of side effects in LEV treated group. Similar to the meta-analysis, we suggest that i.v. LEV can be an alternative treatment of i.v. PHB in children with ARS or SE.

We also compared patient characteristics between responders and nonresponders to i.v. LEV and i.v. PHB. Except for the type of event (SE vs. ARS), no variables were significantly different between responders and nonresponders in each group. This includes etiology, previously used antiepileptic drugs, age, seizure subtype, fever, and presence of provocation factors.

Previous studies have reported inconsistent results about predictors of efficacy of i.v. LEV571618). Reiter et al.16) reported that the mean number of concomitant antiepileptic drugs predicted the effect of i.v. LEV in pediatric patients with acute seizure and did not find any significant effects of age, sex, or seizure classification (single seizure, serial seizure, SE) on seizure termination. Aiguabella et al.5) also suggested that the number of previously used antiepileptic drugs was related to the efficacy of i.v. LEV. By contrast, Isguder et al.18) detected no effect of the number of previously used antiepileptic drugs on the efficacy of i.v. LEV, but suggested that younger age at seizure onset, neurological abnormalities, and West syndrome had a negative influence on response to i.v. LEV in children with ARS. We did not find a relation between the number of previously used antiepileptic drugs and the efficacy of i.v. LEV. However, different inclusion and exclusion criteria and the small number of patients may explain these discrepancies.

In this study, patients treated with i.v. LEV had fewer adverse events than patients treated with i.v. PHB (13.2% vs. 28.0%), although there was no significant difference between the 2 groups. The major adverse event in the i.v. PHB group was lethargy, and this was not observed in the i.v. LEV group. Only mild adverse events such as irritability and vomiting were observed in the i.v. LEV group, which is consistent with previous reports89121621). This reduced sedative effect of i.v. LEV can be useful in patients with SE or encephalitis to allow their mental status to be checked or to shorten the duration of hospitalization.

There are limitations such as the retrospective design of our study. Moreover, we could not define nonconvulsive SE or electrographic seizure due to a lack of 24-hour electroencephalography monitoring after termination of clinical seizures. Despite these limitations, this is the first study to compare i.v. LEV and i.v. PHB in children with SE and ARS, and our results show the efficacy of i.v. LEV for acute seizure control.

Intravenous LEV can be used as an alternative antiepileptic drug to i.v. PHB without severe adverse effects in the acute treatment of ARS. Larger prospective studies are needed to further evaluate the efficacy of i.v. LEV in children with SE, and the pharmacokinetics and loading dose adjustment should be studied to identify the optimal protocol for i.v. LEV delivery.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant (14172MFDS178) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2014.

Notes

Conflicts of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.