Local-food-based complementary feeding for the nutritional status of children ages 6–36 months in rural areas of Indonesia

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to evaluate a pilot project of the Nursing Feeding Center “Posyandu Plus” (NFCPP) through local food-based complementary feeding (LFCF) program designed to improve the nutritional status of children aged 6–36 months at community health centers in Indonesia.

Methods

A quasi-experimental design was used to obtain data regarding the nutritional status of 109 children who participated in the project from 6 rural areas. The NFCPP was conducted for 9 weeks, comprising 2 weeks of preintervention, 6 weeks of intervention, and one week of postintervention. The LFCF intervention consisted of 12 sets of recipes to be made by mothers and given to their children 4 times daily over 6 weeks. The weight-for-age z score (WAZ), height-for-age z score (HAZ), weight-for-height z score (WHZ), and body mass index-for-age z score (BAZ) were calculated using World Health Organization Anthro Plus version 1.0.3.

Results

LFCF intervention significantly increased WHZ, WAZ, and BAZ scores but decreased HAZ scores (P<0.001). Average scores of WHZ (0.96±0.97) and WAZ (0.45±0.72) increased; BAZ increased (1.12±0.93) after 6 weeks of LFCF. WAZ scores postintervention were 50.5% of normal, and WHZ scores were 77.1% of normal. However, the HAZ score decreased by 0.53±0.52, which indicated 57.8% had short stature.

Conclusion

The NFCPP program with LFCF intervention can improve the nutritional status of children in rural areas. It should be implemented as a sustained program for better provision of complementary feeding during the period of lactation using local food made available at community health centers.

Introduction

Some children under 5 years of age are still malnourished, particularly in developing countries1). It is well documented that suffering from undernutrition during early childhood can increase the risk of infections, raise childhood mortality rates, and negatively impact the physical and mental development of children2). In children ages 6–23 months, undernutrition causes growth faltering, which is often accelerated when complementary feeding (CF) starts and breastfeeding is replaced by the feeding of low-nutrient-dense foods. Inadequate macronutrient and micronutrient intake also results from low meal frequency and a lack of diversity in dietary feeding3,4).

Low food intake is still the main cause of undernutrition among children under 5 years in developing countries, particularly those living in rural areas. The prevalences of stunting and underweight in rural areas are 38.1% and 21.7%, respectively, which are higher than those in urban areas (26.4% and 15.3%, respectively)5). Most of developing countries with children suffering undernutrition have enacted programs to overcome this problem6). In the context of Indonesia, programs such as Posyandu have been implemented across Indonesia by the government. To overcome the nutritional problems of young children, Posyandu provides anthropometrical observation, basic medical treatment, and, sometimes, additional CF and health education. However, current data show that a high rate of children are consuming macronutrients and micronutrients below the recommended dietary allowances; this tendency is worse in children in rural areas than in urban areas5,7). In addition, accessibility to food, the affordability of food, and the family's lack of knowledge/skill in preparing food could also be problems for families living in rural areas8).

A local approach to improving the nutritional status of children is needed. The World Health Organization (WHO)/United Nations Children's Fund Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding emphasizes the use of suitable locally available foods. Affordable, available, and locally contextual CF recommendations that take into account cultural diversity and food availability are more likely to result in long-term improvements in CF practices than are general recommendations9). In the Indonesian context, an Integrated Health Service Post (Posyandu) has become the central program for improving Maternal and Child Health10). Posyandu is a community-based effort; it must be carried out by, from, and for the community. Thus, community participation is essential for implementing the basic health effort11). In order to improve its function, Posyandu needed to be reformed as a Nursing Feeding Center (NFC) to facilitate localfood-based complementary feeding (LFCF) within the community.

NFCs in the Indonesian context have helped to encourage mothers to breastfeed exclusively and have provided a sufficient quantity and quality of LFCFs to infants and children ages 6–24 months12 based on the socio-economic status of the family8). The program has the potential to increase people's income through the sale of agricultural products and can be used as a tool in education or nutrition counseling 13). Regarding the importance of aspects of cultural and community development activities while providing CF in the local community, this study uses a LFCF program. Therefore, as recommended by WHO, a program of LFCF practices was implemented to be integrated with Posyandu using a nursing approach called “NFC Posyandu Plus.” This study aims to evaluate the effect of the Posyandu Plus program on the nutritional status of children.

Materials and methods

A quasi-experimental design was used to examine the effects of a 9-week Nursing Feeding Center “Posyandu Plus” (NFCPP) pilot project with local-food based complementary feeding (LFCF) intervention for children ages 6–36 months in six rural areas of East Java Province, Indonesia.

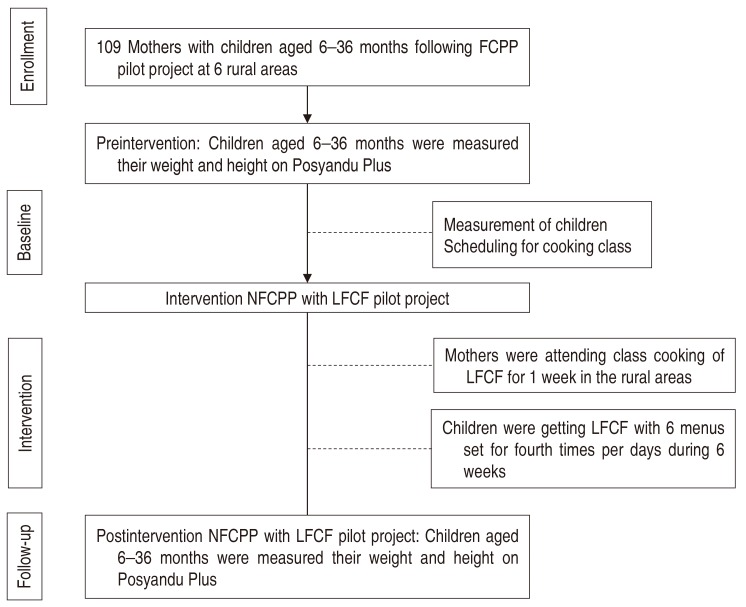

A total of 109 children ages 6–36 months participated in the study. The samples were recruited from 6 subdistricts in rural areas with public health centers. The samples were recruited through a flyer distributed by the public health center to the Posyandu in their working areas. The participants were children, ages 6–36 months, and their parents (mothers breastfeeding exclusively) who had been registered in Posyandu in 6 rural areas. Potential samples met with team members in private rooms at the study sites; appointments were made for group cooking sessions. Furthermore, the samples were divided into six groups in each Posyandu Plus for participating in the NFCPP with LFCF intervention located near the parents' homes (Fig. 1).

Research design of Nursing Feeding Center “Posyandu Plus” (NFCPP) with local food-based complementary feeding (LFCF) intervention in the study area.

The LFCF program used the protocols and measures outlined in the Indonesian Ministry of Health's 2006 National Guidelines for Complementary Breastfeeding (in Indonesian: Pedoman Umum Pemberian Makanan Pendamping Air Susu Ibu (MP-ASI) Lokal Tahun 2006)13). The NFC emphasizes the provision of local CF to increase the nutritional status of children ages 6–36 months. LFCF as the application of innovation in Posyandu Plus priorities should meet the following requirements: food ingredients are easy to obtain, easily processed, affordable, acceptable targets with good nutrient contents that meet the nutritional adequacy target, and with quality proteins that can offer a good return of physical growth (Protein Efficiency Ratio/PER greater than or equal to 70% of the quality of casein, equivalent to >1.75); the type of weaning is adjusted to the target age; is free of germs, preservatives, dyes, and poison; and meets social, economic, cultural, and religious values-that is, some local food made from rice, corn, cassava, sweet potatoes, green beans, and potatoes13). LFCF will feature varied recipes for soft, semisolid, and solid foods (Table 1).

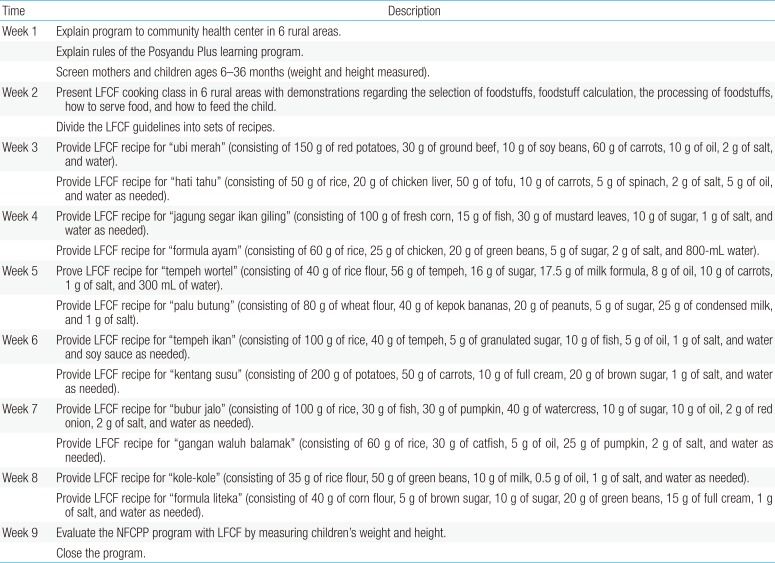

Schedule of Nursing Feeding Center “Posyandu Plus” (NFCPP) with a local-food-based complementary feeding (LFCF) intervention program in rural areas

The NFCPP program with LFCF was carried out in several planned, coordinated, and focused steps that included 8 weeks of activities divided into 6 groups in the rural areas. The NFCPP activities were outlined in the LFCF program guidebook manual. The manual contains the WHO growth chart standard for children and recipes based on local food as an addition to breast milk. The recipes are arranged based on the selection of foodstuffs, foodstuff calculation, the processing of foodstuffs, how to serve food, and how to feed the children. The book also comes with a logbook chart for monitoring the weight and height of the children.

Each group learned how to detect/identify growth in their children and how to set each day's recipe; every week, family homes were visited to obtain local nutritious groceries to be processed by the family independently and for a team of researchers to assess the supplementary feeding and developmental growth of children at participants' homes (Fig. 1). Each week, the family will receive a schedule of different foods to be processed and given to their children. The LFCF is prepared in accordance with the manual, which contains a several diet variations. The food recipes were varied for the six groups and adjusted for potential local foods; however, every diet contained energy density/density of not less than 0.8 calories per gram and protein of not less than 2 g per hundred calories and no more than 5.5 g per hundred calories; the protein quality was not less than 70% Casein standard energy values Proteins have a range between 10%–18%. The content of fat ranged between 1.5 and 4.5 g per 100 calories, given 4 times a day for 6 weeks (Table 1).

A sociodemographic questionnaire identified each participant's age, sex, and area. Anthropometric data were collected using digital weight scales and length boards (for under 24 months) or standing height scale (for 24 months to 36 months), and measurement techniques were based on WHO guidelines14). Both weight and height scales were calibrated to zero before every measurement. All data were collected by a team of well-trained nurses and a nutritionist. To measure the height of children under 24 months, we were lay the child on her back without a pillow (supination), straighten the knee until the stick on the table (the position of the extension), then align the top of the head and lower leg (foot perpendicular to the measuring table) then measure in accordance with the scale shown. Meanwhile, for measurement the height of children aged 24 months to 36 months, height is measured by the upright position, so that the heel of the meeting, while the buttocks, back and back of the head are in a vertical line and attached to the gauges. Then, determine the top of the head and foot sections using a plank with a horizontal position with the legs, then measure in accordance with the scale shown.

Then, height-for-age z score (HAZ), weight-for-age z score (WAZ), weight-for-height z score (WHZ), and body mass index-for-age z score (BAZ) were calculated using the WHO Anthro software version 1.0.315). To classify children's nutritional status, the criteria based on national research of the Ministry of Health of Indonesia were used16). A cutoff point score of <-2.00 standard become deviation for HAZ, WHZ, and WAZ was used to classify stunting, wasting, and underweight, respectively. A z score cutoff point −2.01 to −3.00 for HAZ, HAZ, and WAZ was used to classify severe stunting, severe wasting, and severe underweight, respectively.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee Review Board for Research Center and Community Engagement of the University of Jember No. 1206/UN25.3.2/PM/2013. Then, we obtained ethical and administrative approval from the Department of Political Unity for the Protection of the Public, the National Health Department of each district, and the public health centers. We interviewed and informed the public health centers about the study, and then informed the participants about the study in their area. After receiving permission from the participants, we designed a data collection plan.

This study employed descriptive and comparative data analyses. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were used to summarize categorical measures; means and standard deviation were used to summarize continuous measures. The independent t test was used to analyze: (1) differences in the WHZ, HAZ, WAZ, and BAZ levels preintervention and postintervention by the NFCPP program with LFCF over 6 weeks; and (2) differences in the level of weight per age, height per age, and weight per height preintervention and postintervention by the NFCPP program with LCF over 6 weeks. IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for the analyses. An alpha value of P<0.05 was used to determine the statistical significance.

Results

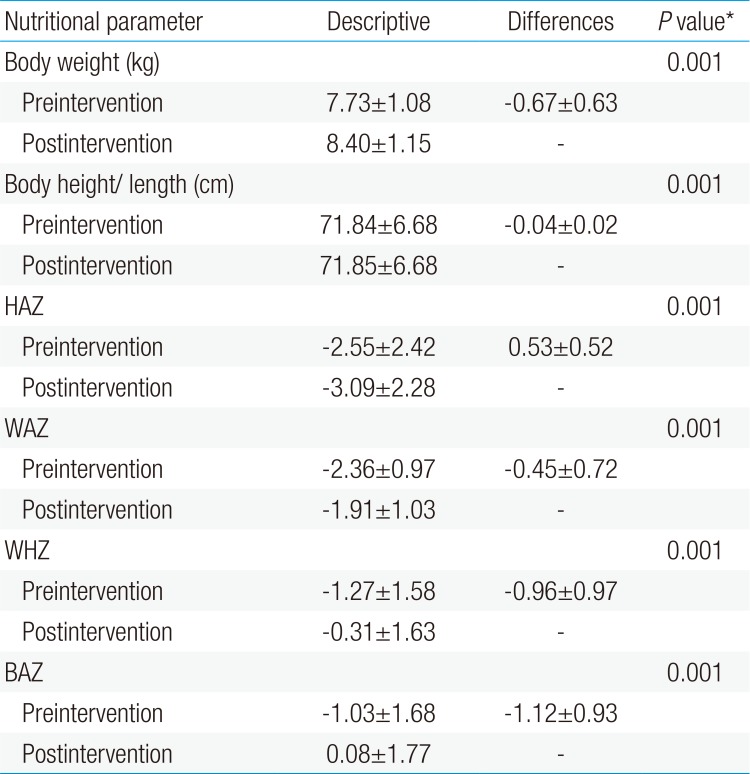

From the total sample of 109 participants, ranging in age from 5.8–28.7 months (15.8±5.24); 59 were boys, and 50 were girls. Table 2 indicates that the mean WAZ, WHZ, and BAZ values after intervention were significantly higher than the baseline data (–2.36±0.97 vs. –1.91±1.03, –1.27±1.58 vs. –0.31±1.63, and −1.03±1.68 vs. 0.08± 1.77, respectively). At the same time, the mean of HAZ after the intervention was found to be lower than the baseline data (–2.55± 2.42 vs. –3.09±2.28).

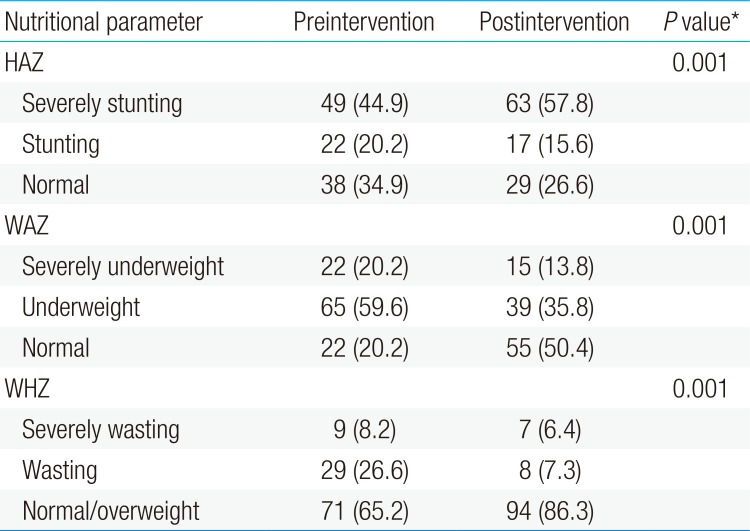

Table 3 shows that there are significant differences in the percentages of the children's nutritional status preintervention and postintervention. Prevalence of children severely underweight decreased from 20.2% to 13.8%, and the percentage of underweight children decreased from 59.6% to 35.8%. After the intervention, the percentages of children suffering severe wasting and wasting were lower than the baseline percentages (6.4% vs. 8.2% and 7.3% vs. 26.6%, respectively). The prevalence of stunting was decreased. However, the percentage of children suffering severe stunting increased from 44.9% to 57.8%, and children with normal body height decreased from 34.9% to 26.6%.

Discussion

The increase in children's anthropometrical parameters, except for HAZ, in this study indicates that LFCF program intervention effectively improves children's body weight. In general, the program was well executed by the Posyandu team (nurses, midwives, nutritionists, and their cadre) and additional nurses. The availability of the program's guidance and preimplementation workshop was mentioned as highly supporting the team's implementation of the program. Adequately skilled nurses and midwives were observed to simplify the training sessions. However, the team reported that weekly supervising families required considerable time due to geographical barriers in rural areas, i.e., teams had to travel great distances from one family's house to another. For further implementation, families could be targeted in small groups (approximately 8–12 families) under the supervision of a cadre; this has been confirmed by previous studies in Indonesia81117).

Families, particularly mothers, responded positively to the program by their attendance at the training and their willingness to implement the program. Mothers reported that they gained more knowledge and skill in cooking various local complementary agricultural foods. It gave mothers a lot of choice regarding recipes for their children. According to mothers, the variability of the recipes fed to children was observed to improve the children's appetites, which is also one factor causing low food intake among children1718). However, in the supervision activities, we found that mothers experienced several constraints, including limited infrastructure for cooking, the sometimes-unwelcome composition of the diet, and limitations in measuring the composition of the food. Mothers sometimes added sugar and flavoring to make the food taste better.

The addition of sugar and salt in the CF for infants due to social and cultural factors in Indonesian society1920). Although based on research results, the use of salt and sugar that is too early in children will lead to obesity or diabetes mellitus and increased blood pressure21), so it is advisable to carry out the addition of the 2 substances in the CF. This is because there occurs maturity taste sensation in the mouth of the baby, so the baby does not need any additional sweeteners or salt in the CF for infants2223). This requires a special approach in providing health education to mothers not to use sugar and salt, especially in children under 2 years and recommends the use of a standard the CF to change the parental perception24).

In general, the availability of cheap and easily accessible food that can be found in the local area increases families' positive feedback regarding the program. The recommendations emphasize that socially and culturally CF should be made of food that is cheap and easily available in the local area (indigenous foods). This is particularly relevant to the 12 recipes provided in the research program. For 6 weeks, the children received LFCF of 2 kinds of diet, given 4 times in a day. The main priority in this program was breast milk or exclusive breastfeeding, to which LFCF should be added.

The findings show that height per age (HAZ) did not increase after the LFCF program; this may be caused by the short time of the program's implementation. Actually, the LFCF program must be done for 90 days for the best results13). On the other hand, the age of the children was increasing, but the height did not increase significantly. These results may be caused in using of measurement for height, that confirmed, standard using a simple vernier capilers to measure of knee-heel length in baby25). However, in this study, we use a standard procedure that we mentioned in the method above to limit the error finding of measurement. The previous research showed that the prevalence of shortness nationally in 2013 was 37.2%, which means an increase over 2010 (35.6%) and 2007 (36.8%). The 37.2% prevalence of shortness includes 18% short and 19.2% very short16). Furthermore, giving local CF has several positive effects, including: mothers' increasing understanding and skill in making food for weaning from local food that fits with local cultural and social habits so that the mother can continue LFCF independently; increasing community participation and empowerment as well as Posyandu strengthening institutionally for health promotion program in Indonesia26); potentially increasing incomes through the sale of agricultural products and education or nutrition counseling.

Other related parameters are needed to evaluate the program comprehensively, such as food intake, biochemical measures, and cognitive development. However, this study has provided as initial evidence of the utilization of local food for CF among agricultural communities in Indonesia. The exploration of other parameters should be included in future studies.

The constraint of this program is related to its short duration, which should be continued for 90 days during the breastfeeding period for infants ages 6–24 months. However, this problem has been overcome by giving LFCF four times a day for 42 days, while the actual standard is 26 days each month with one administration per day. Another problem is that the socio-economic situation in rural areas is considerably lower than standards, meaning that limited funds threaten the program's sustainability. This requires a mutual commitment between the community health centers and Posyandu to provide operational funds for NFCPP activities.

In conclusion, giving local CF is good for improving the nutritional status of infants and children ages 6–36 months. It is one way to restore the proper nutritional status of infants and children from poor families. The giving of LFCF using local food ingredients is expected to have a positive impact on the knowledge and maternal skills for weaning independently, which will in turn improve the nutritional state of the target areas. Moreover, because these activities were carried out in Posyandu, they can also be part of the revitalization of the neighborhood health center and improve societal participation.

To successfully implement the provisions of LFCF will require the understanding of all parties involved, close cooperation between operators and managers, and the commitment of society and families to ensure local children are breastfed. If all components involved in the provision of LFCF function well, LFCF will contribute greatly to efforts to restore the nutritional status of infants and children from poor families. The appropriate implementation of the guidelines will generate optimal results. The regions are expected to implement the program in accordance with the LFCF guidelines.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank you for School of Nursing, University of Jember; Research Center and Community Engagement Department, University of Jember; Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of Indonesia (Kemenristek-Dikti) ad the funder research; Division of Health Science, Graduate Medical, Pharmaceutical and Health Science, Kanazawa University as doctoral study; and Community Health Center of Jember as the areas of research.

Notes

Conflict of interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.