Efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive perampanel treatment in children under 12 years of age with refractory epilepsy

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

There is limited data on the use of perampanel in children under 12 years of age. We evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of adjunctive perampanel treatment in children under 12 years of age with refractory epilepsy.

Methods

This retrospective observational study was performed in Kyungpook National University Hospital from July 2016 to March 2018. A responder was defined as a patient with ≥50% reduction in monthly seizure frequency compared with the baseline. Adverse events and discontinuation data were obtained to evaluate tolerability.

Results

Twenty-two patients (8 males, 14 females) aged 3.1–11.4 years (mean, 8.0±2.5 years) were included in this study. After an average of 9.2 months (range, 0.5–19 months) of follow-up, 15 patients (68%) showed a reduction in seizure frequency, including 5 patients (23%) with seizure freedom. The age at epilepsy onset was significantly lower (P=0.048), and the duration of epilepsy was significantly longer (P=0.019) in responders than in nonresponders. Nine patients (41%) experienced adverse events, including somnolence (23%), respiratory depression (9%), violence (4.5%), and seizure aggravation (4.5%). The most serious adverse event was respiratory depression, which required mechanical ventilation in 2 patients (9%). Eight patients (36%) discontinued perampanel due to lack of efficacy or adverse events. Three out of 4 patients (75%) who discontinued perampanel due to adverse events had an underlying medical condition.

Conclusion

Perampanel offers a treatment option for refractory epilepsy in children. Adjunctive treatment with perampanel requires special consideration in those with underlying medical conditions to prevent serious adverse events.

Introduction

Over the past 20 years, more than a dozen new antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) with different mechanisms of action have been developed. Yet these drugs have not led to a substantial improvement in patients with medically refractory epilepsy [1,2].

Therefore, pharmacoresistant patients require AEDs with novel mechanisms of action [3]. Perampanel, one of the latest AEDs, is the first α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor antagonist [4]. Perampanel inhibits AMPA-induced increases in intracellular Ca2+ and selectively blocks AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission, thus reducing neuronal excitation [5]. Perampanel is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 of the P450 enzyme system, and enzyme-inducing drugs such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin significantly increase the clearance of perampanel and decrease its plasma concentration [3,6].

In patients aged 12 years and older, perampanel is approved for partial-onset seizures with or without secondary generalization, and for primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures [7,8]. Although the adjunctive therapy of perampanel for refractory epilepsy is well established, there is limited data on the use of perampanel in children under 12 years of age, and there are no studies on the use of perampanel involving only children younger than 12 years of age. To evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of perampanel in children under 12 years of age with epilepsy, we performed a retrospective study.

Materials and methods

This retrospective observational study was performed in Kyungpook National University Hospital from July 2016 to March 2018. Medical records from 22 children younger than 12 years of age with various types of epilepsy who had add-on perampanel treatment were reviewed. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the protocol (KNUH-IRB-2018-08-034) and informed consent was waived because of the retrospective nature of the study.

The data collected included the following: sex, age when starting perampanel, age at epilepsy onset, duration of epilepsy, seizure types, etiology, number of concomitant AEDs, concomitant enzyme-inducing AEDs, seizure frequency per month. Seizure types were classified as focal, generalized, combined focal and generalized, and unknown. Epilepsy etiologies classified as structural, genetic, infectious, metabolic, immune, and unknown [9]. To assess efficacy, mean seizure frequency per month during 3 months before perampanel treatment was obtained. The mean starting dosage was 1.4 mg/day (range, 0.5–2.0 mg/day) given once in the evening and was increased every 2–4 weeks up to 1 to 12 mg/day (mean, 3.8 mg/ day) depending on clinical response and tolerability. The criterion for efficacy was based on the seizure frequency during the observation period, compared with baseline. Response was defined as a ≥50% reduction in monthly seizure frequency; seizure freedom was defined as a 100% reduction on a final maintenance dose of perampanel for at least 3 months.

Adverse events and discontinuation data were obtained to assess tolerability. Seizure aggravation was classified as an adverse event. For statistical comparison between responders and nonresponders, the Mann-Whitney test was used for continuous variables and the Fisher exact test was used for categorical variables. Continuous data were presented as means and standard deviations and categorical data as actual numbers and percentages. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

1. Patient population

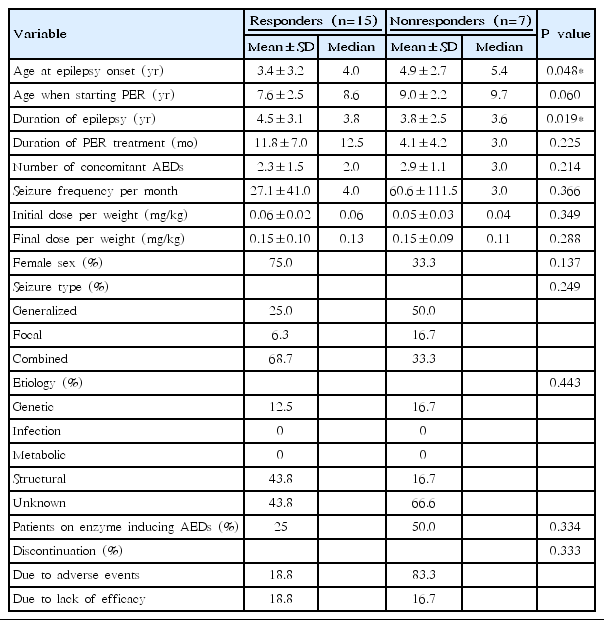

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of patients. We evaluated 22 patients (8 males, 14 females) aged 3.1 to 11.4 years (mean, 8.0±2.5 years). The mean observation period was 9.2 months (range, 0.5–19 months) after the introduction of perampanel. Eight patients (36%) attributed to a structural cause, 3 patients (14%) had a genetic etiology, and 11 patients (50%) had epilepsy of unknown cause. Two patients (9%) had focal seizures, 7 patients (32%) had generalized seizures, and 13 patients (59%) had combined focal and generalized seizures. The mean age at epilepsy onset was 3.9±3.1 years and the mean duration of epilepsy before perampanel treatment was 4.3±2.9 years. Seven patients (32%) were on enzyme-inducing AEDs. The mean final maintenance dose of perampanel was 3.8±2.5 mg.

2. Efficacy

Table 2 demonstrates comparison of demographics and outcomes between responders and nonresponders. Fifteen patients (68%), including 5 patients (23%) with seizure freedom, were responders and 7 patients (32%) were nonresponders. There was no statistical significance between responders and nonresponders in gsex, seizure type, etiology, presence of concomitant enzyme-inducing AEDs, discontinuation rate, age when starting perampanel, duration of perampanel treatment, number of concomitant AEDs, seizure frequency per month, and perampanel dose. Age at epilepsy onset was significantly younger in responders (P=0.048); duration of epilepsy was significantly longer in responders (P=0.019) than in nonresponders.

3. Tolerability

Nine patients (41%) experienced adverse events including somnolence (23%), respiratory depression (9%), violence (4.5%), and seizure aggravation (4.5%). One patient (11%) had severe somnolence when the patient was taking 4.0 mg of perampanel. Since the reduction of perampanel to 2.0 mg, the patient has not displayed any further somnolence. Eight patients (36%) discontinued perampanel due to lack of efficacy or adverse events. Three out of 4 patients (75%) who discontinued perampanel due to adverse events had an underlying medical condition: respiratory depression occurred in 2 bedridden patients previously diagnosed with compromised respiratory function; violence occurred in a patient who had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. One patient in nonresponders had seizure aggravation and discontinued perampanel. The most serious adverse event was respiratory depression which required mechanical ventilation in 2 patients (9%). All adverse events resolved after discontinuation of perampanel. The mean perampanel dose in those who discontinued perampanel due to adverse events was 1.5 mg. Among 7 patients (32%) who had lack of efficacy, 4 patients (57%) discontinued perampanel and the mean perampanel dose was 4.0 mg.

Discussion

Adjunctive treatment with perampanel in children under 12 years of age was efficacious and tolerated as in adults. Sixty-eight percent of the patients showed treatment response, and adverse events seen were generally well tolerated. Factors affecting treatment response were younger age at epilepsy onset and longer duration of epilepsy.

In a study on perampanel tolerability and effectiveness in 58 children and adolescents aged 2 to 17 years (mean age, 10.5 years), response rate after the first 3 months was 31%, which is similar to adult data [10]. In a study of 62 children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 year (mean age, 14.2 years) including 13% of patients aged <12 years, response rate was 50% with that children ≥12 years tended to have a better response (53.7%) than younger children (25.0%) [11]. In another study of 24 children and adolescents treated with perampanel aged 1.5 to 17 years (mean age, 10 year), response rate was 42% [12]. Our patients showed a better response (68%) compared to the previous studies.

Adverse events were reported in 30.6%–60.6% of children and adolescents in previous studies [11,12]. Although most adverse events were acceptable and resolved after dose reduction or discontinuation of perampanel, respiratory depression that required mechanical ventilation was potentially life-threatening. Seventy-five percent of those who discontinued perampanel due to adverse events had an underlying medical condition including compromised respiratory function and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Thus, adverse events should be carefully monitored along with responses especially in patients with underlying medical conditions.

Factors including sex, seizure type, etiology, presence of concomitant enzyme-inducing AEDs, discontinuation rate, age when starting perampanel, duration of perampanel treatment, number of concomitant AEDs, baseline seizure frequency, and perampanel dose did not significantly affect treatment response in our study. Theoretically, enzyme-inducing AEDs are thought to interfere with the metabolism of perampanel. The majority of previous studies, however, have reported that concomitant enzyme-inducing AEDs did not affect treatment response [13,14], which is consistent with our results. Younger age at diagnosis of epilepsy is one of the strongest predictors of intractability on univariate analysis [15]. As age at epilepsy onset was significantly younger in responders, our result suggests that perampanel offers a treatment option for refractory epilepsy in children as in adults.

The main limitations of the current study were the small patient population and the duration of follow-up. Even with the limitations, the difference from previous pediatric studies on perampanel treatment is that our study only includes children under 12 years of age. Further prospective large-scale studies in young children can possibly help lower the proportion of patients with refractory epilepsy.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.