Prevalence and associates of obesity and overweight among school-age children in a rural community of Thailand

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

Information about overweight and obesity among students in rural areas of Thailand is limited. Therefore, we aimed to determine overweight and obesity prevalences and associated factors among school-aged children in a rural community of Thailand.

Methods

We selected 9 public schools through cluster sampling in 2 provinces located in central Thailand in 2016. Anthropometric measurements were measured using standard techniques, classified as overweight (>1 standard deviation [SD]) and obese (>2 SD) with respect to their age and sex using 2007 World Health Organization reference charts. Standardized questionnaires on risk factors were sent to parents to be completed together with their child.

Results

Among 1,749 students, 8.98% had overweight and 7.26% had obesity. Mean age (range) was 11.5 years (5–18 years). Independent factors associated with overweight and obesity included primary school student (reference as secondary school) (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–4.08; P=0.07), mother’s body mass index (aOR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02–1.12; P=0.001), self-employed father (aOR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.12–3.55; P=0.018), number of siblings (aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.47–0.81; P=0.001), having sibling(s) with obesity (aOR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.20–2.77; P=0.005), more than one (aOR, 7.16; 95% CI, 2.40–21.32; P<0.001), consuming 2–3 ladles of rice/meal (aOR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.38–3.32; P=0.001), consuming >3 ladles of rice/meal (aOR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.11–6.46; P= 0.27), watching <2 hours of television/day (aOR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.19–4.01; P=0.012), and watching >2 hours of television/day (aOR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.36–4.96; P=0.004).

Conclusion

Many sociodemographic, dietary, and behavioral factors were related to overweight and obesity among school-aged children not only in urban but also rural communities of Thailand.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) described the prevalence of overweight and obesity as having increased substantially over the past three decades and now being considered one of the most serious health challenges of the early 21st century [1]. Overweight and obesity are major risk factors for noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorder, and some cancers. In addition to these risks, childhood obesity is associated with a high chance of obesity, premature death, and disability in adulthood as well as experiencing breathing difficulties, increased risk of fractures, hypertension, early markers of cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance and, psychological effects [2].

In Thailand, the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity has risen (4th Thailand Health Survey 2008–2009) to be 8.5% among those aged 1–5 years, 8.7% among those aged 6–11 years, and 11.9% among those aged 12–14 years, constituting the highest rate of all age groups [3]. Studies in many parts of the world have generally agreed that the factors contributing to increased childhood obesity are multiple interactions between genetic factors and the environment [4]. These associated factors include higher socioeconomic status [5,6], higher birth weight [7,8], dieting [9,10], skipping breakfast [11,12], physical inactivity including less active modes of transportation to and from school, lack of participation in sports activities at school or at home [9,13-15], as well as long hours spent watching TV and playing video games [7,9,16]. In contrast to the genetic factors, the relationship between lifestyle and other factors have been found to be inconclusive. These inconsistencies are likely to result from differences in methods and the cultural and social backgrounds of the studied populations. Better understanding of the factors associated with obesity would help general public healthcare providers and healthcare professionals to deal with the epidemic more efficiently.

Very little data is available concerning the prevalence of overweight and obesity among school children and adolescents in rural areas of Thailand. The present study aimed to assess the prevalence of overweight, obesity, and associated risk factors among school children and adolescents in rural areas of Chachoengsao and Sa Kaeo provinces, Eastern Thailand.

Materials and methods

1. Study design

This cross-sectional study was performed, from June to December 2016, to assess the prevalence and risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among school-aged children in rural area of Chachoengsao and Sa Kaeo provinces, Eastern Thailand, using a cluster sampling and a survey of 2,246 students in 9 schools located in Na Yao Community, Sanam Chai Khet District, Chachoengsao Province and Sai Thong Community, Khao Cha Kan District, Sa Kaeo Province in Thailand.

2. Study populations

Students aged 6 to 18 years first to twelfth grade who studied in 1 of the 9 schools who had with no mental health issues, and who were able to communicate and willing to participate with the consent of their guardians, were included in the research while students who did not meet these criteria were excluded.

3. Ethical statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Royal Thai Army, Medical Department (approval number: 1514/2559). The researchers informed subjects and their parents of the objective and asked for permission from each school’s principals and teachers to collect data from participants. Informed consent was obtained from enrolled participants for actions in which participants’ height and weight were measured and questionnaires were voluntarily answered.

4. Study procedures

The study comprised two sections, anthropometric measurement and the questionnaire. The questionnaires consisted of general information, parental information, and associated risk factors of overweight and obesity such as lifestyle, diet, and physical activities. To collect body mass index (BMI) from each participant, the school’s advisors were asked and taught to measure students’ weight and height properly. Body weight and height were measured with standardized 101 balance scales (DETECTO, St. Webb City, MO, USA) (to the nearest 0.1 kg) and stadiometer (DETECTO) (to the nearest 0.1 cm), respectively. Students’ weight and height were measured while students were wearing school uniforms without shoes and socks while waist circumference was not measured. BMI, the weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters, was calculated. Overweight, obesity, thinness, and severe thinness were defined using BMI reference (2007) for age and sex cutoff points developed by the WHO and using >2 SD to define obesity, >1 SD as overweight, -<2 SD as thinness, and -<3 SD as severe thinness [17]. Then questionnaires were distributed to participants without personal identification. The participants filled in the data with their parents or guardians voluntarily. The completed questionnaires were collected in sealed boxes placed in selected schools. After collection of the data, pamphlets with general information about obesity and overweight including healthy practices, were distributed to every student in the selected schools to educate the students regarding obesity and overweight.

5. Statistical analysis

The data was collected and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and STATA SE ver. 13 (StataCorp LP., College Station, TX, USA). The t test was used in quantitative indices and was expressed as mean±standard deviations. The relationship between each factor of interest and the students’ BMI group (severe thinness, thin, normal, and overweight or obesity) was explored with percentages (%) or chi-square tests (categorical variables). Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the strength of the relationship between overweight in students and each of those variables of interest. Variables with significant associations (P<0.05) with students’ BMI group in the chi-square tests were considered for logistic regression. Odds ratios (ORs) and the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated for each factor. Using a mixed method model of multivariate analysis with random effect of school type variable, adjustment was made for parental obesity to control for possible familial influences. A 2-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

From a total number of 2,246 students from 9 schools aged 6 to18 years from 9 schools (mean±SD, 11.8±3.6), 1,749 students participated in this study, because 497 did not complete questionnaires or did not agree to have their height and weight measured. Thus, the total response rate was 77.9%. Of the total respondents, 981 (56.1%) were females, and the number of primary school students (first through sixth grades) was 1,114 (63.7%), while the remaining 635 (36.3%) comprised secondary school students (seventh through twelfth grades).

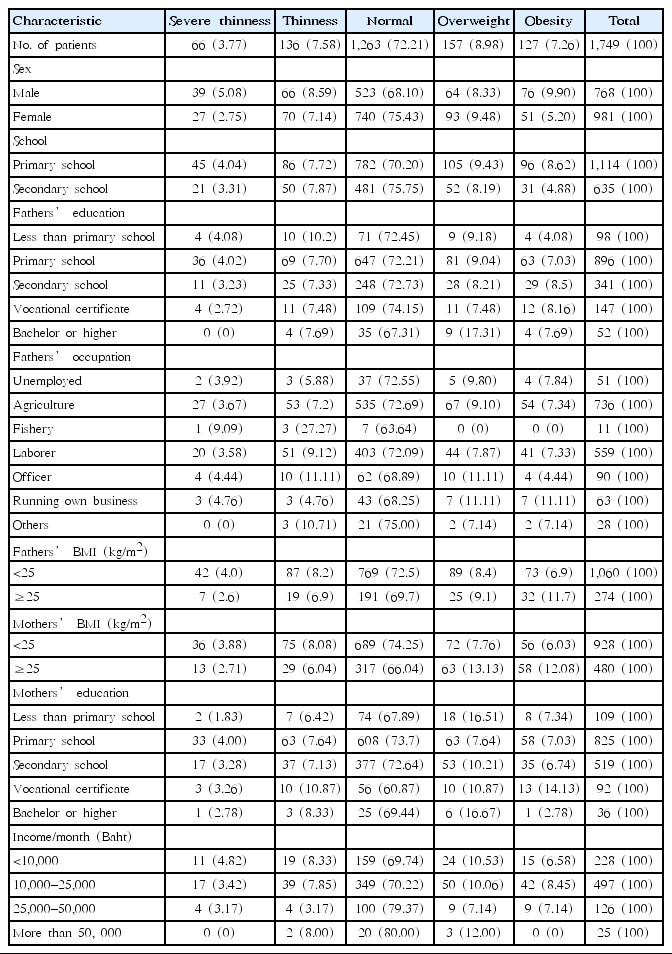

Table 1 show the background characteristics of children who participated in the study and their BMI. Of the 1,749 children who participated, 157 (8.9%) were overweight and 127 (7.3%) were obese. Among the boys, 64 (8.3%) were overweight and 76 (9.9%) were obese, while among the girls, 93 (9.5%) were overweight and 51 (5.2%) were obese. Prevalence of overweight and obesity significantly differed among primary school students and secondary school students.

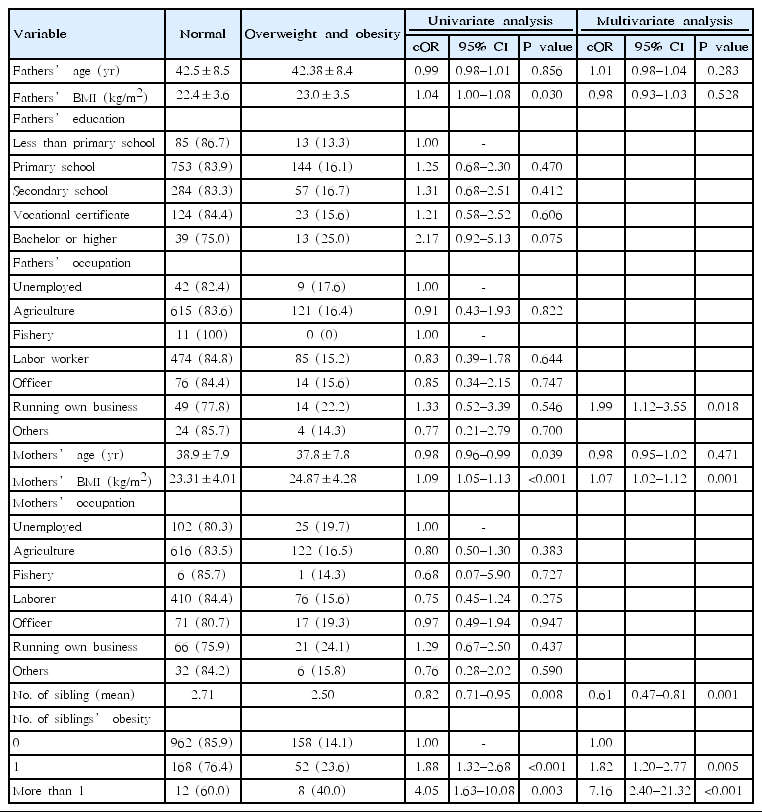

As shown in Table 2, after adjusting for the potential confounding factors, we found that these family-related factors were significantly associated with overweight and obesity, including maternal BMI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.07; 95% CI, 1.02–1.12; P=0.001) and parents’ running their own business (aOR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.12–3.55; P=0.018). In addition, in Table 3, after adjusting for the potential confounding factors, we found that these child behavioral factors were significantly associated with overweight and obesity, including students who were in primary school (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 2.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24–4.08; P=0.07), number of siblings (aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.47–0.81; P=0.001), obesity in one sibling (aOR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.20–2.77; P=0.005), obesity in more than one sibling (aOR, 7.16; 95% CI, 2.40–21.32; P<0.001), consuming two to three ladles of rice per meal (aOR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.38–3.32; P=0.001), consuming 2 to, 3 ladles of rice per meal (aOR, 2.69; 95% CI, 1.11–6.46; P=0.27), spending 2 hours or less per day with a television or smartphone (aOR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.19–4.01; P=0.012), spending 2 hours or more per day with a television or smartphone (aOR, 2.60; 95% CI, 1.36–4.96; P=0.004).

Univariate and multivariate analysis of family-related risk factors associated with overweight and obesity among school-aged children in a rural community in Thailand

Discussion

The prevalence of overweight and obesity among school-aged children in the current study were 8.98% and 7.26%, respectively, resulting in a prevalence of overweight and obesity together at 16.24%. From the 4th Thailand Health Survey 2008 to 2009, the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity increased to 8.5% among children aged 1–5 years, 8.7% among children aged 6–11 years, and 11.9% among children aged 12–14 years.

From the study of prevalence of overweight and obesity in Thai population: results of “the National Thai Food Consumption Survey” [18]. The data showed; overall, among children and adolescents aged 3 to 18 years, 9.1% were overweight and 6.5% were obese. Also, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in urban areas were 3.5% and 3.9%, respectively and in rural areas 5.6% and 2.6% respectively. Our findings on the prevalence of overweight and obesity among school-aged children were quite similar to these of these 2 studies. Although prevalence of overweight and obesity was commonly found in urban communities, there was no statistically significant difference in overweight and obesity rates between those who lived in urban areas and those who lived in rural areas. Our findings are in agreement that in both genders, the highest prevalence of overweight was found in school-aged children (6–11 years) and decreased with age.

The findings of the current study indicated that family history of obesity was obviously related, and maternal obesity was independently associated with overweight or obesity among school-aged children. Those having a positive maternal obesity had 1.07 times the risk of overweight or obesity. A similar finding was also reported in other studies in Hong Kong, China, and western India [8,19,20]. Also, having overweight or obese siblings made overweight or obesity more likely for subjects. Students with one overweight or obese sibling had 1.82 times the risk of being overweight or obese themselves and those who had more than one overweight or obese sibling had 7.16 times the risk. These findings may have resulted from many factors, including socioeconomic factors. As reported in studies conducted in rural areas of Thailand, the bond between children and their mothers in rural societies is unyielding. This affects children’s way of life, with children tending to have the same preferences, eating habits, and level of physical activities as their mothers. Thus, children with obese mothers tend to grow up to be overweight or obese, like their mothers, and this tendency extends to siblings living in the same family environment.

Students with more siblings had 0.61 times the risk of being overweight or obese than those with fewer siblings. Similar findings have been reported by studies conducted in Norway and Tanzania [21,22]. The explanation of this result is that it depends on the economic status of the family. A higher number of family members means more expenses affecting the quality of life of each family member, namely decreasing the total amount of food available for each family member at each meal

Overweight and obesity prevalence were also higher among students who spent more time doing sedentary activities such as watching TV, playing computer games, or using electronic devices. Students who spent less than 2 hours and at least 2 hours watching TV, playing computer games, or using electronic devices exhibited a risk of overweight or obesity that was 2.18 times and 2.60 times higher, respectively. Several studies have reported a positive association between increased BMI and decreased physical activity [7,9,16,23].

The relation between grade level and prevalence of obesity in this study indicated that primary school students (first through sixth grades) were 2.25 times more likely to develop overweight or obesity compared with those in secondary school (seventh through twelfth grades). This study was conducted in a rural area of Thailand where the major occupation of the community was in agriculture. Grown-up children tended to follow their parents’ path as farmers or were at least expected to help the family to farm. The outcomes included decreased sedentary activities and increased high energy consuming activities, relatively lowering their body weight. Hence, ways of livings impacted the obesity trends in the communities.

Our study also revealed that parents’ occupation was significantly associated with overweight and obesity. Children with parents who ran their own business had a risk that was 1.99 times higher than the risk in students whose parents had other occupations. Families running their own businesses tended to have higher incomes, meaning that their children had a greater potential to spend money on more food, to have better welfare, to use more sedentary transportation, to perform less housework, and to do less active work, which created a higher risk of developing childhood obesity. This was supported by other studies wherein higher socioeconomic status was associated with obesity and overweight [5,6].

Diet-related variables were also studied using multivariate analysis. Overweight and obesity were significantly associated with the amount of rice consumed at each meal, with rice measured in ladles at 70 g per ladle. The number of ladles was associated with students’ overweight or obesity: 2 to 3 ladles of rice per meal increased the risk of being overweight or obese by 2.14 times, and consuming more than three ladles of rice per meal increased the risk by as much as 2.69 times. Basically a higher energy intake coupled with the same daily living activities resulted in weight gain. In addition, the relationship between family income and number of ladles per meal was shown in the Table 3, but there was no association between these 2 variables. This might be explained by the relatively homogenous study population in terms of family incomes. The majority of the participants had relatively low economic statuses, as only 25 families had a reported income of more than 50,000 baht per month (about USD 1,500). In addition, as most of the participants were from farming families, there was more than enough rice for the whole family’s consuming. Therefore, the number of ladles per meal might not have been associated with the family income since every family had enough rice for their consumption

From the study, factors not associated with overweight and obesity in this population included skipping breakfast, similar to one study in Tianjin, China [19]. That study revealed that having breakfast, snacks, and carbonated drinks had no relationship with childhood obesity and overweight because the study population had been consuming these unhealthy foods previously. In addition, one study of other factors including physical activity, birth weight, and transportation to school found no significant association between these factors and obesity and overweight in these populations. This was in contrast to another study in China, where these factors were significantly associated with overweight or obesity.

Furthermore, this study showed that 198 school-aged children (11.28%) presented thinness or severe thinness. It suggested that some associated factors could be further studied. Moreover, interventions like nutrition education for patients, school cafeteria menu planning, and family member involvement would be helpful for this study population to develop a better nutrition status.

This study employed a cross-sectional design which had its own limitations. An obvious limitation stemmed from the fact that the nature of the study precluded statements of cause and effect and explanations of temporal relationships. Also, BMI calculation, from weight and height measurement, sometimes could not determine whether an increase in body weight was truly derived from an increase in fat because a body composition monitor device was not used. In addition, parent BMI data was collected using questionnaires, and not by actual measurement but by recall response. Moreover, data errors tended to occur because information for absent family members needed to be completed, so recall bias or missing data would have occurred when other family members could not remember or misremembered the absent individual’s information.

Using the WHO 2007 reference, the prevalence of overweight and obesity among school-aged children in Baan Na Yao, Chachoengsao Province and Baan Sai Thong, Sa Kaeo Province in Thailand was 8.98% and 7.26%, respectively, making the total prevalence of overweight and obesity 16.24%. Sociodemographic predictors related to overweight or obesity included maternal and sibling obesity, number of siblings, and parents’ occupation (running their own business), where the number of ladles of rice per meal was a significant diet-related variable, and sedentary activities such as watching TV, playing computer games, or using electronic devices were found to be significant predictors of overweight and obesity. Yet the prevalence of underweight was 11.28%. Household members, especially mothers and children, should be motivated to have sufficient healthy food and be physically active by limiting sedentary activities and enjoying outdoor activities with other family members. Good quality, healthy food should be regulated by school policy, and outdoor sports and related activities should be mandated as well.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our appreciation to all participants for their enthusiastic support in this study. In addition, I would also like to extend our sincere thanks to Thananan Nijjak, Nattanon Mekawanith, Bodin Chokdamrongsuk, Pasin Charnviboon, Pochong Uthaitas, Patcha Jeandejaporn, Ratchanon Buakhwan, Vutthikorn Khingmontri, Sirada Udombhakdibongse, Supphanut Sukkasem, Sinsup Wanikawetch, and Ruengwit Tantibhedhyangkul for their helpful suggestions and data collection.