Comparison of diagnostic and treatment guidelines for undescended testis

Article information

Abstract

Cryptorchidism or undescended testis is the single most common genitourinary disease in male neonates. In most cases, the testes will descend spontaneously by 3 months of age. If the testes do not descend by 6 months of age, the probability of spontaneous descent thereafter is low. About 1%–2% of boys older than 6 months have undescended testes after their early postnatal descent. In some cases, a testis vanishes in the abdomen or reascends after birth which was present in the scrotum at birth. An inguinal undescended testis is sometimes mistaken for an inguinal hernia. A surgical specialist referral is recommended if descent does not occur by 6 months, undescended testis is newly diagnosed after 6 months of age, or testicular torsion is suspected. International guidelines do not recommend ultrasonography or other diagnostic imaging because they cannot add diagnostic accuracy or change treatment. Routine hormonal therapy is not recommended for undescended testis due to a lack of evidence. Orchiopexy is recommended between 6 and 18 months at the latest to protect the fertility potential and decrease the risk of malignant changes. Patients with unilateral undescended testis have an infertility rate of up to 10%. This rate is even higher in patients with bilateral undescended testes, with intra-abdominal undescended testis, or who underwent delayed orchiopexy. Patients with undescended testis have a threefold increased risk of testicular cancer later in life compared to the general population. Self-examination after puberty is recommended to facilitate early cancer detection. A timely referral to a surgical specialist and timely surgical correction are the most important factors for decreasing infertility and testicular cancer rates.

Key message

Primary caregivers should consider surgical specialist referral of patients with undescended testis if no descent occurs by 6 months, undescended testis is newly diagnosed after 6 months of age, or testicular torsion is suspected. Orchiopexy is recommended between 6 and 18 months at the latest. The original location of the testes and the age at orchiopexy are predictive factors for infertility and malignancy later in life.

Introduction

Cryptorchidism or undescended testis (a testis that is not in the scrotum) is the single most common genitourinary disease in male neonates [1]. Normal testicular descent to the scrotum usually occurs between 25 and 35 weeks of gestation [2]. Undescended testis is diagnosed at birth at a rate of 1%–4% in term infants and up to 45% in preterm infants [3]. Many cases of undescended testes will descend spontaneously to the scrotum by 3 months of age [4]. Testicular descent after 3 months of age is also possible, especially in preterm infants [5]. However, in some preterm infants, the testes do not descend until term age or vanish in the abdomen. In some cases, a testis that was present in the scrotum reascends after birth. The mechanisms of normal testicular descent, testicular reascent, and testicular regression have not been fully established yet. About 1%–2% of boys older than 6 months develop undescended testis after its early postnatal descent [6]. Undescended testis is known to be associated with decreased fertility and increased malignancy rates [7,8]. Timely referral to a surgical specialist and timely surgical correction may improve fertility rates and decrease malignancy rates related to undescended testis. Controversy persists about the effectiveness of hormonal therapy, timing of surgical therapy, and testicular outcomes of undescended testis. In this review, we discuss the diagnosis, differential diagnosis, hormonal therapy, and timing of surgical therapy of undescended testis based on international guidelines as well as fertility and the risk of testicular cancer of undescended testis.

Risk factors

Important risk factors of undescended testis are preterm birth (<37-week gestation), low birth weight (<2.5 kg), and intrauterine growth restriction [9]. A family history of undescended testis, associated hormonal disorders (such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia), associated penile abnormalities (such as hypospadias), slow fetal growth (such as Down syndrome), and disorders of sex development can increase the risk of undescended testis. A young maternal age is protective against the development of undescended testis [10]. Older maternal age is related to undescended testis [11]. The relative risk is 1.8 with a maternal age ≥30 years and 2.5 with a maternal age ≥40 years. However, controversy persists regarding the role of maternal old age and the development of undescended testis. Maternal smoking during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of undescended testis [12,13]. A history of previous surgery for inguinal hernia or orchiopexy can also increase the risk of undescended testis [14].

Classification

Testicular position is classified as intra-abdominal, inguinal, supra-scrotal, high scrotal, and scrotal according to the process of testicular descent [14,15]. Intra-abdominal testis is not palpable. Inguinal testis is sometimes palpable. Supra-scrotal and high scrotal testes are palpable. Scrotal testis is considered normal, as it lies in the bottom of the scrotum (Fig. 1).

Testicular position. Testicular position is classified as intra-abdominal, inguinal, supra-scrotal, high scrotal, and scrotal according to the process of testicular descent. Intra-abdominal testes are not palpable. Inguinal testes are sometimes palpable. Supra-scrotal and high scrotal testis is palpable. Scrotal testis is considered normal as it lies in the bottom of scrotum. UDT, undescended testis.

Undescended testis is classified according to its location and presence (Table 1). In palpable undescended testis, the testis may be palpable in the inguinal canal or ectopic area such as the inner thigh, femoral, pubic, and perineal regions. In impalpable undescended testis, the testis may be located in the abdomen, inguinal canal, or internal inguinal ring. It may also be absent. When the testis is found in the scrotum, sometimes in a suprascrotal position, it is called retractile testis and has finished its descent. It can be pulled gently to the bottom of the scrotum and may stay there for a while, which is often considered normal [16]. However, up to one-third of retractile testis can reascend and become undescended, which is not considered normal [3]. Reascended testis, which a previously descended testis ascends to a higher position, comprises some proportion of cases of undescended testis. An abnormally persistent fibrotic remnant of the processus vaginalis [17], patent processus vaginalis, and nonorthotopic gubernacular insertion (higher insertion) [18] are suggested causes of reascended testis.

Diagnosis

The external genitalia must be inspected thoroughly, especially in patients whose bilateral testes are not palpable. Bilateral impalpable testes can be associated with hormonal failure, conditions such as prune belly syndrome, a posterior urethral valve, abdominal wall defects, or neural tube defects [19]. The patient’s groin and scrotum must be palpated from the inguinal canal toward the pubis in a supine or frog-leg position with warm fingers. The inner thigh, femoral, pubic, perineal, and penile regions also must be palpated to find the ectopic testis. Testis can become palpable in a sitting or squatting position but not in a supine position [20].

Unilateral impalpable testis associated with contralateral compensatory hypertrophy suggests the absence of the ipsilateral testis, meaning vanishing testis or testicular regression [21,22]. Antenatal vascular accident [23] and underlying antenatal endocrinopathy are 2 suggested important pathogeneses of testicular regression. Antenatal vascular accident is caused by arrested endothelial cell migration and disturbed endothelial cell development rather than testicular torsion [24]. However, intrauterine torsion of the gonadal vessel and failure of the intrauterine testicular blood supply may also cause testicular agenesis or in utero infarction and atrophy of normal testis, resulting in vanishing testis or testicular regression [3,25]. The prevalence of monorchidism (unilateral absent testis) is up to 4%, while that of anorchidism (bilateral absent testes) is less than 1% among patients with undescended testis [3].

Female infants presenting with bilateral inguinal hernia may be androgen insensitivity syndrome male with inguinal undescended testis [26,27]. Inguinal hernia or mass in infancy is among the most common presentations of androgen insensitivity syndrome, although it is usually diagnosed at adolescence with primary amenorrhea. Some researchers recommend chromosomal analysis in female infants with bilateral inguinal masses to diagnose androgen insensitivity syndrome [27].

Transverse testicular ectopia is a rare condition in which both testes migrate through one inguinal canal caused by a disturbance in testicular descent [28,29]. Unilateral impalpable testis and contralateral inguinal hernia are common presentation of transverse testicular ectopia. Most of the patients are diagnosed during surgery for inguinal hernia, at which time the testes are placed in one hemiscrotum. Diagnostic exploratory laparoscopy is helpful for detecting associated anomalies [28].

Routine endocrine assessment of unilateral undescended testis is not recommended. However, an endocrine assessment for bilateral undescended testes is required based on guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA) [30], the British Association of Pediatric Surgeons/British Association of Urologic Surgeons (BAPS/BAUS) [31], the Canadian Urological Association (CUA) [32], and the European Association of Urology (EAU) [33] (Table 2). Diagnostic exploratory laparoscopy is recommended to identify impalpable undescended testis, which is the gold standard with great sensitivity and specificity [30-33].

Imaging studies

In a systemic review, ultrasonography could not determine whether a testis is present or localize impalpable testes. It also could not rule out an intra-abdominal testis [34]. Similarly, in cases of impalpable undescended testis, diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging is low to determine the presence of the testis or the absence of intra-abdominal testis [35-37]. The AUA [30], BAPS/BAUS [31], CUA [32], and EAU [33] guidelines do not recommend ultrasonography or other diagnostic imaging, although the former is not invasive, because it cannot add diagnostic accuracy or change treatment (Table 2).

Some practitioners perform ultrasonography to evaluate undescended testis before and after orchiopexy [38]. Practically, ultrasonography is used because of uncertainty of the diagnosis. According to the nationwide questionnaire detailing the practice patterns of undescended testis in Korea (distributed to 167 Korean urologists), most urologists performed diagnostic imaging studies for unilateral impalpable undescended testis [39]. Fifty-two percent performed ultrasonography alone, while 40% performed ultrasonography and other imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography. The suggested reasons for performing imaging studies were that they may add objective assessments of pre- and postoperative testicular size and help any legal problem following orchiopexy. Only 8% did not perform imaging studies, citing that imaging studies cannot change management and diagnostic exploratory laparoscopy is inevitable regardless of the results (Table 3).

Hormonal therapy

Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) stimulates testicular hormone synthesis and enables the testes to descend into the scrotum. Intramuscular hCG therapy was first introduced in 1930 to treat undescended testis. However, hCG therapy can cause germ cell apoptosis, penile growth, pubic hair, frequent erection, behavior problems, and injection site pain in up to 75% of patients [40-42]. There is a lack of documentation to prove the long-term efficacy of hCG therapy. A significant reascending rate after descending has been reported [43]. Thus, hCG therapy is not justified anymore for undescended testis [44]. Intranasal gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) analog was introduced in 1974. The success rate of testicular descent with intranasal luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) therapy was as low as about 20% in prescrotal or inguinal palpable undescended testis, but not in impalpable testis [41]. However, LHRH therapy can cause hydrocele requiring surgery, penile growth, pubic hair, frequent erection, and behavioral problems [41]. GnRH/LHRH therapy can also harm germ cells and suppress their numbers [45]. Long-term follow-up of GnRH/LHRH therapy has not been reported yet. Besides, the success rate of testicular descent with hormonal therapy is low and the risk of testicular reascending is high, although the testes descend with hormone therapy. On the other hand, in a small study of 10 boys, GnRH agonist therapy with orchiopexy improved impaired mini-puberty and spermatogonia in patients with bilateral undescended testes [46].

According to international guidelines, routine hormonal therapy with hCG or GnRH/LHRH for undescended testes. is not recommended due to the lack of evidence as previously described (Table 4) [30,32,33]. Consensus is developing that orchiopexy but not hormonal therapy is required in the first year of life [30,47,48]. In an identified hormonal defect in congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism or partial androgen insensitivity, hormonal therapy can be considered by a pediatric endocrinologist. However, debate persists over whether hormonal therapy is useful as an adjunct to orchiopexy to stimulate germ cell development, although hormonal therapy for undescended testes is ineffective.

Surgical therapy

If the testes do not descend at 6 months of age, the probability of spontaneous descent thereafter is low [49]. International guidelines recommend surgical specialist referral from primary caregivers if descent does not occur by 6 months [30-33], or if undescended testis is newly diagnosed after 6 months of age (Table 2) [30,32].

Undescended testis interferes with the differentiation of primitive germ cells that produce germ cells and finally spermatogenesis [44]. Thus, delayed orchiopexy decreases germ cell production, testicular volume, and fertility [50]. To enhance spermatogenesis and increase testicular volume, the recommended age of orchiopexy decreased from 48–72 months in 1986 to 18–24 months and recently 6–12 months of age [51,52]. However, large number of boys still undergo orchiopexy after 18 months of age. The median age for orchiopexy was 48 months between 1993 and 2000 and 36 months between 2000 and 2010 in 3784 orchiopexies over 22 years [51]. The most common age at orchiopexy was 12–18 months. The second most common age was 18–30 months between 1993 and 2014 [51]. Among patients undergoing orchiopexy, 77% were older than 1 year and 42% were older than 2 years at orchiopexy [6].

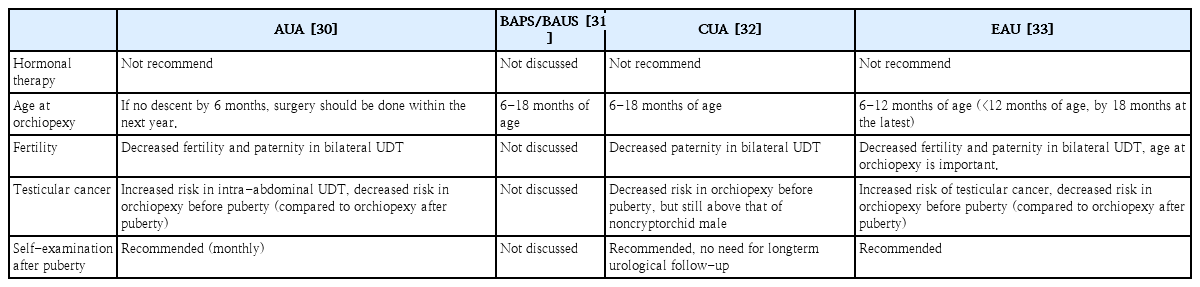

Histological evidence suggests that orchiopexy should be performed within the first year of life (no later than 2 years of age) to protect fertility [53]. A recent systematic review found no difference in testicular volume or spermatogonia in orchiopexy before versus after 1year of age, although better fertility potential with orchiopexy performed before 1year of age was found [54]. To protect fertility potential and decrease malignant changes, surgical exploration and orchiopexy are recommended between six and 18 months of age (Table 4).

Testicular torsion, a surgical emergency, is not common in neonates, and torsion of undescended testis does not present the typical painful swelling of the scrotum; rather, it appears as swelling of the groin. Therefore, torsion of undescended testis is not easy to recognize. Undescended testis and an ipsilateral inguinal mass with groin swelling must be suspected as torsion of undescended testis. Ultrasonography is not helpful to differentiate between incarcerated inguinal hernia and torsion of undescended testis; rather, urgent referral and surgical exploration are required [55].

Undescended testis and fertility

Hutson et al. [56] reported that gonocytes transform into spermatogenic stem cells at 3–9 months of age. This postnatal step is confused in cases of undescended testis. Arrested gonocytes in undescended testis can cause germ cell malignancies after puberty. Abnormalities in gonocyte transformation can cause infertility. Thus, the original location of the undescended testis is important in the risk of testicular cancer and fertility. Age at orchiopexy is also an important factor for predicting fertility [33].

Compared to fertility rate (number of offspring born per mating pair) in the general population, that in patients with undescended testis is decreased, although they underwent orchiopexy. Patients with bilateral undescended testes have an increased infertility rate compared to those with a unilateral undescended testis and the general population [57]. Infertility rates of patients with unilateral undescended testis are up to 10%, which is even higher in patients with bilateral undescended testes [58,59]. The paternity rate (actual potential of fatherhood) was reportedly 62% in bilateral undescended testes, 89% in unilateral undescended testis, and 94% in the general United States population [60]. The paternity rate among patients with bilateral undescended testes was as low as 33%–65% in Canada. In cases of unilateral undescended testis, it was similar to that in a general Canadian population (up to 90%) [32]. Testicular atrophy has been reported in less than one third of patients, depending on the original location, despite the success of surgical procedures [49]. Intra-abdominal undescended testis is associated with a high risk of postsurgical atrophy despite successful orchiopexy, which is 15-fold higher than inguinal undescended testis [58]. Untreated bilateral undescended testes show a 100% oligospermia rate [61]. Patients with bilateral undescended testes without germ cells on biopsy show a 75%–100% risk of infertility [62].

Undescended testis and testicular cancer

In a meta-analysis, patients with undescended testis are at a threefold increased risk of testicular cancer later in life [7]. In another study, the risk of testicular cancer is increased sevenfold in patients with undescended testes and 32-fold if orchiopexy is delayed after puberty [63]. A significantly increased risk of testicular cancer in intra-abdominal testis was reported in the past. However, the risk of testicular cancer decreased in patients who underwent orchiopexy before puberty compared to those who underwent orchiopexy after puberty [30,63,64]. The relative risk of testicular cancer in patients who underwent orchiopexy before puberty (<13 years of age) was 2.2, which increased to 5.4 in patients who underwent orchiopexy after puberty versus the general population [64].

Formal long-term urological follow-up of patients with undescended testes is not recommended [32]. Screening and self-examination during and after puberty are recommended because of the increased risk of testicular cancer (Table 4).

Conclusion

Timely referral to a surgical specialist and timely surgical correction may improve fertility and decrease malignancy rates related to undescended testis. Primary caregivers should consider surgical specialist referral of patients with undescended testis if no descent occurs by 6 months, undescended testis is newly diagnosed after 6 months of age, or testicular torsion is suspected. The use of ultrasonography and other diagnostic imaging techniques is not recommended because they cannot add diagnostic accuracy or change treatment. Orchiopexy is recommended between 6 and 18 months at the latest. The fertility rate is low in patients with bilateral undescended testes, although orchiopexy is successful. The risk of testicular cancer in patients with undescended testis is increased compared to that in the general population. The original location of the testes and the age at orchiopexy are predictive factors for fertility and malignancy later in life. Self-examination after puberty is recommended to facilitate early cancer detection.

Notes

See the commentary “Undescended testis: importance of a timely referral to a surgical specialist” via https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2020.00115.

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.