Myths and truths about pediatric psychogenic nonepileptic seizures

Article information

Abstract

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) is a neuropsychiatric condition that causes a transient alteration of consciousness and loss of self-control. PNES, which occur in vulnerable individuals who often have experienced trauma and are precipitated by overwhelming circumstances, are a body’s expression of a distressed mind, a cry for help. PNES are misunderstood, mistreated, under-recognized, and underdiagnosed. The mindbody dichotomy, an artificial divide between physical and mental health and brain disorders into neurology and psychiatry, contributes to undue delays in the diagnosis and treatment of PNES. One of the major barriers in the effective diagnosis and treatment of PNES is the dissonance caused by different illness perceptions between patients and providers. While patients are bewildered by their experiences of disabling attacks beyond their control or comprehension, providers consider PNES trivial because they are not epileptic seizures and are caused by psychological stress. The belief that patients with PNES are feigning or controlling their symptoms leads to negative attitudes of healthcare providers, which in turn lead to a failure to provide the support and respect that patients with PNES so desperately need and deserve. A biopsychosocial perspective and better understanding of the neurobiology of PNES may help bridge this great divide between brain and behavior and improve our interaction with patients, thereby improving prognosis. Knowledge of dysregulated stress hormones, autonomic nervous system dysfunction, and altered brain connectivity in PNES will better prepare providers to communicate with patients how intangible emotional stressors could cause tangible involuntary movements and altered awareness.

Key message

• Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) are events that look like epileptic seizures but are not caused by abnormal electrical discharges.

• PNES are a manifestation of psychological and emotional distress.

• Treatment for PNES does not begin with the psychological intervention but starts with the diagnosis and how the diagnosis is delivered.

• A multifactorial biopsychosocial process and a neurobiological review are both essential components when treating PNES

Introduction

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are paroxysmal attacks that may resemble epileptic seizures but are not caused by abnormal brain electrical discharges. At least 15 different labels have been used to describe PNES, including dissociative attacks, hysterical epilepsy, psychogenic seizures, nonepileptic spells, nonphysiologic or functional seizures, and pseudoseizures (a term now widely considered pejorative) [1]. PNES, the most common functional neurological disorder, falls under the diagnostic category of somatic symptom-related disorder, previously known as conversion disorder or conversion reaction [2]. PNES are a manifestation of psychological distress, the body’s way of expressing what the mind and mouth cannot [3]. PNES are a dissociative response to threatening internal or external stimuli that likely resulted from the interaction of multiple predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors [4]. One can imagine that the brain becomes overloaded and shuts down in a freeze mode, switching off as if in response to a threatening trigger, so fleeting a response that the patient is unaware.

Providers may feel that PNES is a stress-related mental phenomenon, whereas patients hold markedly different beliefs and views about PNES [5,6]. Patients (and their families) feel their seizures could not possibly be related to “stress.” [7] A history of sexual or physical abuse is a common risk factor for the development of PNES [2,3]. The unique risk factors for pediatric PNES include school difficulties, learning disabilities, or bullying [8]. However, people with PNES often do not know why they occur and remain unaware of their emotional experience, failing to find the link [7]. Patients often cannot identify the cause of their emotional or mental stress [2]. Thus, there is obvious dissonance and disconnection in the belief and understanding of PNES between patients and treating physicians [6]. While the symptoms are involuntary, improvement can only occur with the patient’s active and very conscious participation. Symptoms of PNES may have transactional value such as avoidance, and this understanding of a subconscious or unconscious drive may allow a point of intervention. Benbadis said it best when he wrote, “PNES are a real condition that arises in response to real stressors. These seizures are not consciously produced and are not the patient’s fault.” [3,9] PNES and factitious disorder/malingering are completely different disorders: symptoms of the former are not consciously produced and do respond to psychotherapy, whereas those of the latter are consciously produced and do not respond well to psychotherapy [10].

PNES are a relatively common condition encountered by pediatricians and neurologists and among the most important differential diagnoses of pediatric epilepsy. This entity constitutes the most common nonepileptic event in school-aged children and adolescents, accounting for 3.5%–15% of pediatric patients referred for video electroencephalography (vEEG) [11,12]. In adults, about 10% of outpatients in epilepsy clinics and 30% of inpatients in epilepsy monitoring units reportedly have PNES [13]. The International League Against Epilepsy Commission ranked PNES among the top 3 neuropsychiatric disorders related to epilepsy [14]. People with PNES are considered unwelcomed consumers of health care services, such as emergency room visits, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), antiseizure medications, and hospital admissions resulting in an increased health care utilization costs [15]. The lifetime dollar cost per year in the PNES patient cohort is $110–920 million in the United States alone [15]. Unfortunately, the high medical costs related to the condition fail to translate to improved care and prognosis for patients with PNES. Many patients with PNES quit school or work [16,17]. In fact, their health-related quality of life is poorer than patients with epilepsy [18].

Pediatric patients with PNES and their families report receiving inadequate treatment and supportive care compared with patients with epilepsy [19]. Children with PNES often fall through the cracks between the specialties of neurology and psychiatry, because there is a sense that they are welcome in neither area [5]. Neither of these professionals is willing or prepared to assume treating this complex condition [20]. Psychiatrists tend to be skeptical of the diagnosis of PNES and question the accuracy of vEEG [10,21]. Neurologists are primarily focused on ruling out epilepsy, and many feel that any aspect of the treatment of PNES is not their responsibility [5,10]. Because of the gaps in diagnostic and therapeutic services, many patients feel left in limbo [5]. In this review, we will discuss challenges of PNES from delivery of diagnosis, the current limited understanding of neurobiology and biopsychosocial aspects, and a hypothesis of the pathophysiology of the condition. We hope that a better understanding of its etiopathology will convince providers that PNES is indeed a brain disorder. Such understanding may lead to better care, treatment, and prognosis for patients with PNES.

How to deliver the diagnosis of PNES: a barrier to communication because of a dualistic conceptualization.

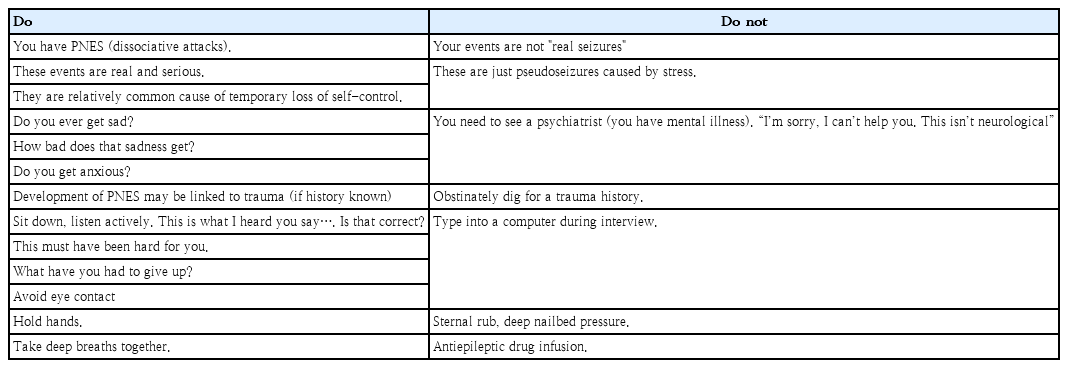

The essential step in initiating the treatment of PNES is delivering the confirmed diagnosis in an understanding and nonjudgmental manner [22,23]. How the diagnosis is communicated and explained affects the patient’s prognosis, in particular, the manner in which the diagnosis is communicated is as important as the specific words that are used, and diagnostic clarity is essential [23]. Table 1 summarizes the suggested delivery of the diagnosis. The physician must communicate the diagnosis with conviction and not hesitate or “beat around the bush.” [23] Psychoeducation can then follow to inform the patients and their families how stress or emotions can affect the body.

In a study investigating who delivered the diagnosis of PNES to patients, over 70% were neurologists [24]. This result is not surprising because neurologists are responsible for caring for patients who present with seizures in many medical centers. If neurologists take the responsibility of diagnosing and explaining PNES, how comfortable and equipped are they to communicate the diagnosis to patients? What is the main barrier? Unfortunately, many neurologists express feelings of discomfort and frustration when presenting the diagnosis of PNES [25]. Poor communication of the diagnosis is often the main obstacle to effective treatment [23]. A study exploring interactional resistance between neurologists and PNES patients demonstrated that patients were exceptionally resistant when doctors explained the emotional causes of the problem and recommended psychological treatment [26]. Numerous studies reported that most physicians believe that psychological factors are the main or sole etiology of PNES [5,25,27]. Some physicians believe that PNES are voluntarily induced [27]. In contrast, most patients consider themselves mentally healthy and perceive PNES as a biological disorder [6,28]. This mismatch in illness perception disrupts physician communication and patient acceptance of the diagnosis [5]. If the patient refuses to accept the diagnosis or explanation for their nonepileptic seizures, then there is no basis for psychotherapeutic intervention [5]. Despite considerable research delineating the biopsychosocial and neurobiological underpinnings of PNES, many physicians remain uncertain about the plausible biological processes and causes of PNES symptomology [5]. Here we introduce a multifactorial biopsychosocial process and review the neurobiological evidence in PNES to bridge the gap in illness perception between physicians and patients.

Multifactorial biopsychosocial model of PNES

The etiology of PNES is complex. Any single etiology or even contributing factor fails to fully explain the heterogeneous PNES patient population [4]. Instead, PNES can be best understood via a biopsychosocial model [4], which has been generally applied to functional neurological disorders [29]. According to this model, the etiological factors of PNES can be categorized under predisposing, precipitating, and perpetuating factors [4]. Predisposing factors increase the vulnerability and risk of a child to developing PNES in later life [4]. These include biological constitutions, such as genetics, temperament, or neurologic comorbidities and early life traumatic experiences, such as childhood neglect and sexual or physical abuse [4]. Precipitating factors refer to a specific event that seems to trigger PNES, which typically occur over days to months before symptom onset [4]. Stressful experiences, conflicts, and physical or mental health problems are among the precipitating factors of PNES. Perpetuating factors maintain PNES once it has become established; these include a lack of social support, avoidance, isolation, or a sick role [4]. Several of these factors interact with each other and can be identified in most patients with PNES [4,17]. Compared with adults, youth with PNES have a more complex profile of interrelated biopsychosocial risk factors [8,17,30]. Extensive literature exists about the neurophysiologic mechanisms of antecedent early life experiences and temperament, 2 of the major predisposing factors of PNES [31,32].

Neurobiological aspects of PNES

This review focuses on the 2 key findings of the neurobiology of PNES: (1) an increased arousal index; and (2) alterations in the cognitive-emotional-executive control circuitry in the brain’s connectivity network.

1. Increased arousal index in patients with PNES

1) Basal hypercortisolism

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a primary mechanism in the allostatic process through which early life stress contributes to disease [33]. Cortisol, a polypeptide hormone that is integral to stress processing, is released from the adrenal cortex in response to adrenocorticotropic hormone, which is released in response to the hypothalamic secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone. Once the stressors or threatening stimuli are removed, the glucocorticoid level is normalized by negative feedback. Dysregulation of this stress neurocircuitry is the most common feature across stress-related neuropsychiatric diseases such as depression and posttraumatic stress disorder [34].

Studies on the relationship of PNES to these neurobiological stress systems have shown dysregulation of the stress hormone homeostasis (Table 2). Tunca et al. [35] found decreased cortisol suppression after dexamethasone administration but no differences in basal cortisol levels in blood samples of patients with conversion disorders (including patients with PNES) compared with healthy controls. They interpreted that supervening depressive symptoms in conversion disorder may contribute to disruption of the HPA axis function. Bakvis et al. [36] reported significantly increased basal diurnal cortisol levels in patients with PNES compared with healthy controls. In contrast to Tunca et al. [35,37], Bakvis et al. [36] showed that basal hypercortisolism in patients with PNES was not explained by depression or concurrent seizures but rather by the history of sexual abuse. They suggested that increased HPA axis activity in patients with PNES may not reflect current physical or acute psychological stress but posit a relevant neurobiological marker of its mechanisms [36]. The elevated diurnal cortisol level and decreased sensitivity to dexamethasone suppression are consistent with hypercortisolism in patients with PNES.

How is cortisol involved in the PNES manifestation? Some studies used cortisol as a stress marker and found no difference in prestress basal cortisol levels between patients with PNES and others [38-40]. In contrast, basal cortisol level appears to positively correlate with automatic avoidance tendencies [41], threat vigilance [39], and working memory impairments [40] to social threat cues or emotional stress in patients with PNES. These findings suggest that stress hormones may be involved in hyperarousal or dysregulation of social-emotional stimuli in PNES.

2) Basal and preictal autonomic arousal in patients with PNES

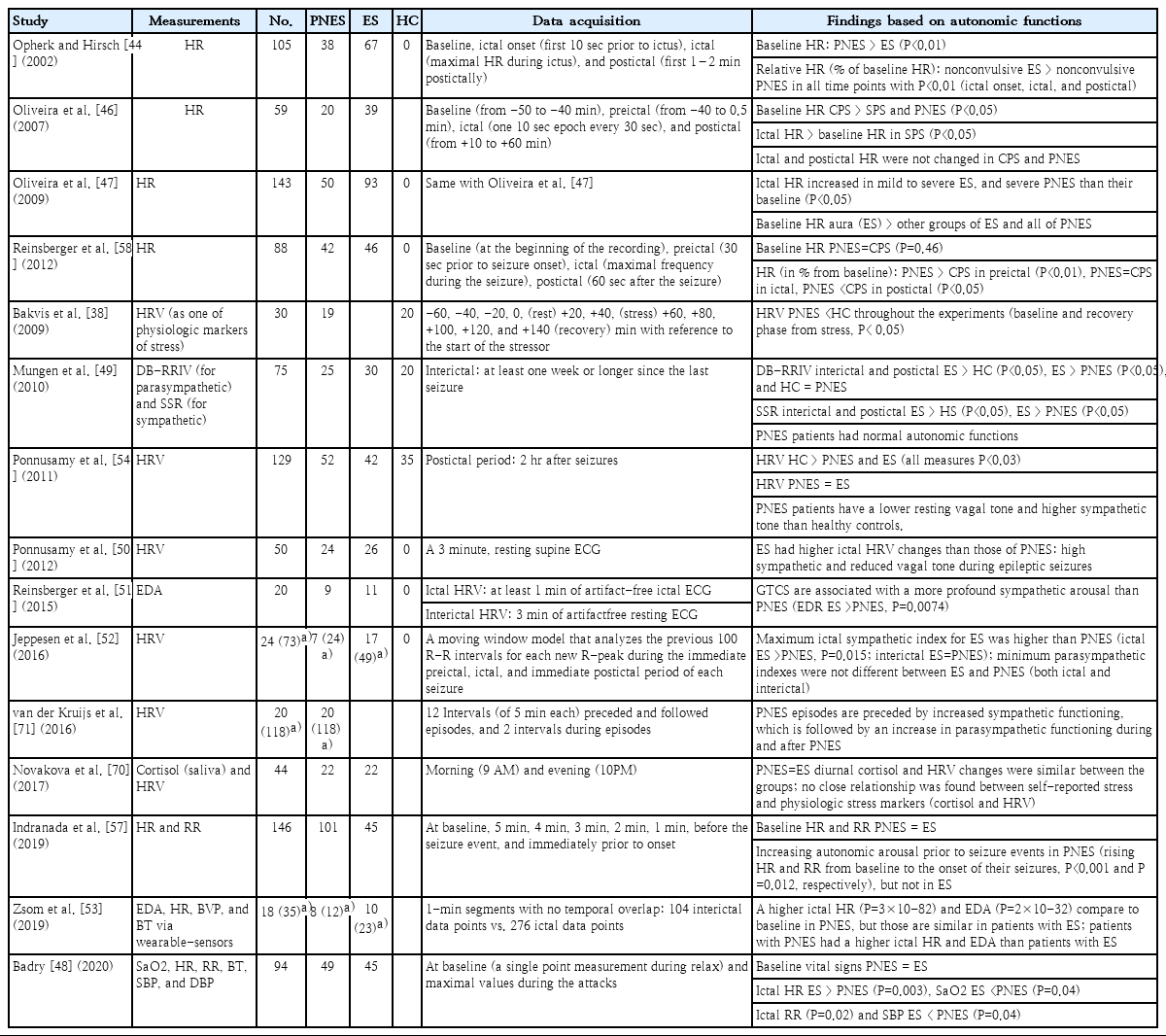

Autonomic nervous system (ANS) dysfunction has been increasingly recognized to play a role in numerous neuropsychiatric disorders, including PNES. However, most research on PNES compared small heterogeneous cohorts of patients with PNES or epilepsy [42]. ANS appears to be directly involved in epileptic seizures via centrally mediated sympathetic and parasympathetic system activation by hypersynchronous epileptiform discharges [43]. Thus, ictal tachycardia is a proposed marker for seizure detection [44,45]. Moreover, vagal nerve stimulation is a treatment option for drug-resistant epilepsy. In contrast, PNES has heterogeneous psychiatric comorbidities, such as posttraumatic stress syndrome, generalized anxiety disorder, and major depressive disorder, that may have different and variable manifestations of ANS dysfunction. It is not surprising then that, unlike epilepsy, PNES lacks a consistent ANS response. A higher ictal heart rate (HR) [44,46-48] and profound sympathetic activation [49-52] during seizures have been reported in patients with epilepsy versus patients with PNES in most studies comparing the autonomic function between them. Only one study reported contradictory results of a higher ictal HR [53] in PNES than in epileptic seizures (Table 3).

Studies focusing on ANS function at rest (interictal period) or its preictal changes of PNES have been more revealing. HR variability (HRV) was low in patients with PNES at rest versus normal controls [54]. A significant reduction in HRV occurred at baseline and after recovery from acute social stress induction in patients with PNES versus normal controls [38]. HRV is widely used as a standard index for assessing ANS functions, because a lower HRV is a reliable indicator of reduced parasympathetic activity. The parasympathetic system is a “buffer” that allows individuals to react properly to external stimuli. In addition, decreased HRV is related to increased arousal and anxiety [55] and reduced ability to cope with internal and external stressors [56]. Therefore, sustained baseline vulnerability, such as hyperarousal or low vagal tone at rest, may underlie the pathophysiology of PNES [38,51]. An acute temporal sequence analysis of preictal HR showed a significantly rising HR from baseline toward seizure onset in patients with PNES but not in patients with epilepsy [57]. A study comparing preictal, ictal, and postictal HR differences in patients with PNES and epileptic controls identified significant preictal HR increases in the former [58]. Together with previous studies, these findings suggest that PNES events are likely to occur when autonomic arousal surges in the absence of adequate buffering from the parasympathetic nervous system.

2. Connectivity changes in brain networks in PNES

Alterations in the intrinsic connectivity of the brain in patients with PNES have been explored using functional MRI (fMRI), which analyzes fluctuations in the blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal, which is indirectly correlated with neuronal activity. Resting-state fMRI (rsfMRI) measures synchronous activations of the BOLD signal between brain regions to investigate the functional intrinsic connectivity of the brain [59]. In contrast, task- or event-related fMRI infers certain areas of the brain in which activation occurs during the performance of a task or in response to a stimulus [59]. We chose to review selected well-designed case-controlled fMRI studies below (Table 4).

1) Lost optimal network topology in patients with PNES

Ding et al. [60] simultaneously investigated structural and functional connectivity in patients with PNES using rsfMRI and diffusion tensor imaging while searching for a potential imaging biomarker for patients with PNES. They found that patients with PNES had a suboptimal “small-worldness” in their functional and structural connectivity networks compared with normal healthy controls [60]. Specifically, large-scale brain networks shift toward a more regular (lattice-like) organization [60]. Small-worldness is a fundamental organization principle in the brain network that has unique properties of regional specialization with efficient information transfer [61]. In contrast, regular networks have a lower potential for global integration with a less efficient information transfer [60]. They also found that the coupling of functional-structural connectivity was decreased in PNES [60]. Finally, they postulated that patients with PNES have abnormal brain network mechanisms and a less optimal topological organization of functional and structural connectivity [60].

2) Altered resting-state cognitive-emotional-executive control network

Van der Kruijs et al. [62] first reported the altered functional connectivity of PNES using rsfMRI. Patients with PNES had a stronger connection between brain regions involving emotion (insula) and the precentral sulcus (motor planning) or the parietal lobe (processing of sensory information) than their normal healthy counterparts [62]. A significant positive correlation was noted between dissociation scores and functional connectivity values of the insular-precentral sulcus [62]. These findings suggest that increased connectivity between the brain regions involved in emotional processing and motor planning can bypass the inhibitory control provided by the frontal brain regions and result in involuntary movements [62]. A subsequent study further demonstrated that alterations of the resting-state networks involving frontoparietal activation, executive control, sensorimotor functioning, and the default mode were related to the dissociation occurring in patients with PNES [63].

Similar findings were replicated by other researchers. Li et al. [64] found that functional connectivity values between brain regions involving motor functions and an insular subregion were positively correlated with PNES attack frequency. Thus, abnormal emotional-motor mechanisms of the brain network may predispose an individual to PNES [64]. Ding et al. [65] found a correlation between disease duration and hyperactivation of the occipital cortex to visual stimuli in patients with PNES and suggested that such an increased response to external stimuli may reflect an adaptive change in these patients to chronic hypervigilance. Dienstag et al. [66] added an interesting aspect of long-term memory involvement in PNES pathogenesis by demonstrating impaired connectivity between the medial temporal lobe (MTL), a brain region involved in autobiographical memory, and the sensorimotor cortex, and between the MTL and the ventral attention network in patients with PNES [66]. Their findings support their hypothesis that PNES symptoms result from psychological defense mechanisms used by patients to “block” their awareness of traumatic memories [66]. Two recent studies assessed the functional connectivity of the amygdala, which has been implicated in emotion processing and the pathology of PNES, to other brain regions. Compared with patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, those with PNES showed an increased resting-state functional connectivity between the amygdala and brain circuits involved in emotional regulation and motor control [67]. These results suggest that abnormalities in emotional processing create an increased propensity to seizures precipitated by heightened stress in patients with PNES [67]. Allendorfer et al. [68] evaluated the psychological stress response in the brain regions involved in emotional-motor-executive control in PNES. Using fMRI, they demonstrated hyporeactivity in the amygdala to psychological stress along with greater emotional-motor-executive control network resting-state functional connectivity in patients with PNES versus healthy controls [68]. Allendorfer et al. [68] suggested dysregulation of the stress response circuitry involving the emotional-motor-executive control network in PNES. All of these findings are supportive of the previous findings of the emotional processing network of patients with PNES in that emotion drives involuntary motor symptoms by overriding executive control in patients with PNES. Thus, generations of PNES appear to be related to altered attention, sensorimotor, and emotional system connectivity.

3) Task- or event-related fMRI in PNES

Only 3 studies to date have analyzed task- or event-related fMRI and rsfMRI findings in patients with PNES. Differences in cortical responses to facial emotional processing between patients with PNES and temporal lobe epilepsy were noted; specifically, patients with PNES exhibited increased fMRI responses to happy, neutral, and fearful faces in the visual, temporal, or parietal regions and decreased fMRI responses to sad faces in the bilateral putamen [67]. Psychological stress responses in the brain regions showed hyporeactivity in the amygdala and left hippocampus in patients with PNES versus healthy controls [68]. Van der Kruijs et al. [62] found no significant differences in many task-related paradigms (picture coding, emotional stimuli, Stroop color-naming, susceptibility to hypnotic induction related to dissociation) between patients with PNES and normal healthy controls in an overall brain analysis.

Conclusions

Psychogenic PNES superficially resemble seizures, although unlike epileptic seizures, they are not induced by abnormal electrical activity in the brain. PNES are a physical manifestation of psychological distress, a dissociative state, and a common cause of transient loss of awareness and consciousness. Patients with PNES are often blamed for their symptoms as if they are making them up when, in fact, they are frightened, unaware of their emotional stress, and unable to find the mind-body link. PNES are as costly and disabling as epileptic seizures, although the health-related quality of life of patients with PNES is worse than that of patients with epilepsy. The diagnosis and treatment of PNES are often delayed because of barriers to care. It is important to recognize and communicate to patients that PNES is indeed a brain disorder, life experiences can change the brain to make one vulnerable to PNES, and the condition will improve with intervention. PNES may be considered a normal reaction to an overwhelming experience that exceeds and overloads a person’s nervous system and coping ability. Evidence shows that patients with PNES have heightened reactions to external or internal stress in the HPA axis and a dysregulated ANS. Functional connectivity is altered in patients with PNES, particularly in brain networks involving the cognitive-emotional-executive control circuitry. These changes may reflect an adaptation to long-term hypervigilance and an increased response to stressful stimuli. The truth about PNES lies beyond the dualistic framework of psychologic versus biologic. Rather, an integrative and inclusive biopsychosocial perspective is more suitable for addressing PNES, a condition that lies at the interface of neurology and psychiatry. One needs to break down the artificial divide between physical health and mental health and recognize the inseparability of the mind and body.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Gyeongsang National University Fund for Professors on Sabbatical Leave, 2019.