Obesity and chronic kidney disease: prevalence, mechanism, and management

Article information

Abstract

The prevalence of childhood obesity is increasing worldwide at an alarming rate. While obesity is known to increase a variety of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, it also acts as a risk factor for the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). During childhood and adolescence, severe obesity is associated with an increased prevalence and incidence of the early stages of kidney disease. Importantly, children born to obese mothers are also at increased risk of developing obesity and CKD later in life. The potential mechanisms underlying the association between obesity and CKD include hemodynamic factors, metabolic effects, and lipid nephrotoxicity. Weight reduction via increased physical activity, caloric restriction, treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and judicious bariatric surgery can be used to control obesity and obesity-related kidney disease. Preventive strategies to halt the obesity epidemic in the healthcare community are needed to reduce the widespread deleterious consequences of obesity including CKD development and progression.

Key message

· Obesity is strongly associated with the development and progression of chronic kidney disease.

· Altered renal hemodynamics, metabolic effects, and lipid nephrotoxicity may play a key role in the development of obesity-related kidney disease.

· Children born to obese mothers are at increased risk of developing obesity and chronic kidney disease later in life.

· A multilevel approach is needed to prevent obesity and related chronic diseases.

Introduction

Childhood obesity has been recognized as one of the most serious public health concerns worldwide [1]. Children with obesity often remain obese in adulthood and carry an increased risk of adverse clinical outcomes, including kidney disease [2-4]. Obesity is a key feature of metabolic syndrome, which is characterized by a group of cardiovascular risk factors, including central obesity, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and hyperglycemia [5]. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing concomitant with obesity [6]. The number of patients at all stages of CKD was approximately 700 million in 2017, and the age-standardized CKD mortality rate increased by 41.5% from 1990 to 2017 [7]. The prevalence of CKD in the pediatric population has also increased steadily, and children and adolescents with CKD have a dramatically increased risk of death [8,9]. Obesity, diabetes mellitus (DM), and hypertension increase the risk of CKD. Obesity is strongly associated with the development and progression of CKD [5]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity among women of reproductive age is increasing rapidly, and evidence suggests that maternal obesity increases the risk of chronic diseases in offspring, including obesity and CKD [10-12]. Therefore, obesity is recognized by the pediatric nephrology community as a significant health challenge [13]. This review discusses the epidemiology of obesity, the effect of obesity on renal outcomes, the mechanisms of obesity in kidney disease, management of obesity-related kidney disease in children and adolescents, and evidence supporting the role of maternal obesity in the developmental programming of chronic diseases, especially CKD, in offspring.

Epidemiology and definition of pediatric obesity

Obesity in children of all ages has increased over the last 4 decades. Globally, the age-standardized prevalence of obesity from 1975 to 2016 increased from 0.9% to 7.8% among boys and from 0.7% to 5.6% among girls [14]. It is estimated that 38.2 million children aged <5 years were overweight or obese worldwide in 2019 [1]. Developing countries are undergoing a rapid epidemiological transition from normal weight to overweight and obesity, with rates similar to those observed in European countries and the United States many years ago [15]. Obesity increases the risk of DM, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and CKD.

The definition of pediatric obesity based on high body mass index (BMI) in children depends on percentile cutoffs specific for age and gender. In children, overweight is defined as a BMI greater than or equal to the 85th percentile and lower than the 95th percentile, and obesity is defined as a BMI greater than or equal to the 95th percentile [16]. The American Heart Association defines severe obesity as a BMI ≥120% of the 95th percentile or an absolute BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 [17]. Severe obesity in childhood and adolescence increases the risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease in adulthood [18].

The adverse effects of obesity on renal outcomes

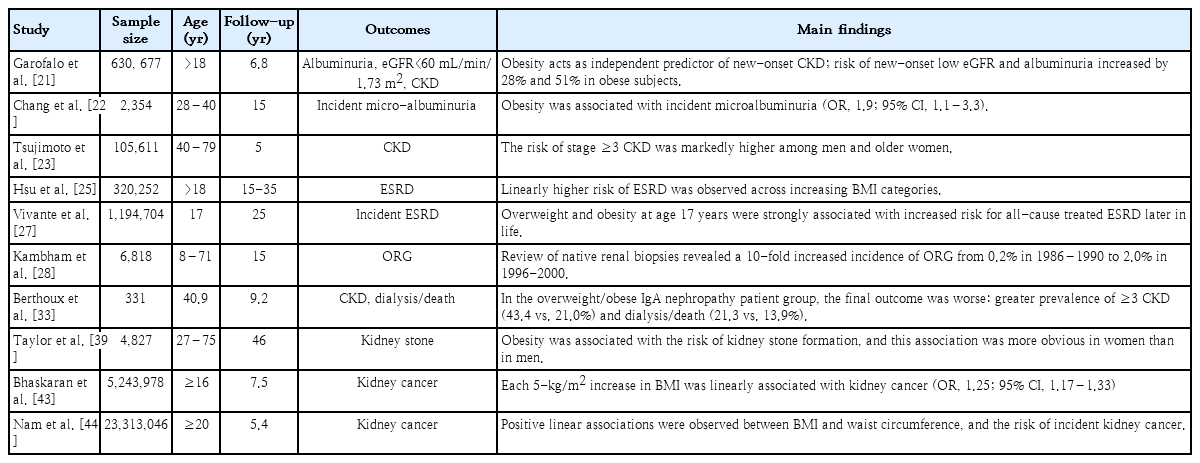

Obesity is an important predisposing factor for CKD and endstage renal disease (ESRD) [19]. Wang et al. [20] have shown that 24%–33% of all kidney disease cases in the United States are associated with obesity. Similarly, there is a link between obesity and the development and progression of CKD, and individuals with higher BMI carry a greater risk of developing proteinuria even without kidney disease [21,22]. Obesity predicts new-onset CKD and represents an independent risk factor for CKD progression regardless of underlying nephropathy [23-25]. Higher baseline BMI was an independent predictor of ESRD after adjusting for baseline comorbidities, such as hypertension and DM [25]. Obesity in childhood and adolescence is associated with CKD and ESRD [19]. The prevalence of overweight and obesity in a pediatric population on renal replacement therapy in Europe was 20.8% and 12.5%, respectively [26]. A long-term nationwide population-based study revealed that overweight and obesity in adolescents were strongly correlated with an increased risk of allcause ESRD [27]. In a study of 1.2 million adolescents followed for a mean of 25 years, obese adolescents aged 17 years showed a 3.4-fold higher risk of developing nondiabetic ESRD and a 19-fold greater risk of developing diabetic ESRD, indicating a substantial association between elevated BMI in adolescence and diabetic and nondiabetic ESRD [27].

Obesity is related to a secondary form of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) known as obesity-related glomerulopathy (ORG). The incidence of ORG has increased worldwide in parallel with the increase in the prevalence of obesity. In a 15-year study, Kambham et al. [28] reported that the incidence of ORG in native kidney biopsies increased 10-fold, from 0.2% in 1986–1990 to 2.0% in 1996–2000. In this series, 56% of obese patients had proteinuria, and 44% showed proteinuria and renal insufficiency. Histologically, the perihilar variant of FSGS is predominantly associated with ORG, and podocyte foot process effacement in ORG is less severe than that in primary FSGS [29,30]. Although some patients show nephrotic-range proteinuria and the progressive deterioration of renal function [29], the most frequent clinical manifestation of ORG is subnephrotic proteinuria. The limited presence of full nephrotic syndrome in patients with ORG can be clinically significant since a progressive increase in proteinuria may go unnoticed for years, leading to late diagnosis of renal failure [29]. Many studies suggest that obesity-associated insulin resistance increases the risk of CKD progression following a period of “silent” glomerular hyperfiltration [31,32]. Obesity is significantly related to the development and progression of renal diseases other than ORG [29,33-38]. In patients with immunoglobulin A nephropathy, hypertension, proteinuria≥1 g/day, and severe histopathological lesions at diagnosis were more frequent in the overweight and obese groups [33]. Overweight and obesity increased the risk of interstitial fibrosis in patients with IgA nephropathy, suggesting a connection between BMI and IgA nephropathy progression [34]. In a pediatric cohort with proteinuric kidney diseases, the glomerular volume was larger in obese children than in nonobese children with FSGS [35]. In this cohort, obese children born preterm carried a 2-fold higher risk of developing ESRD than obese patients born at term and a 5-fold greater risk of progressing to ESRD than nonobese preterm children [36].

Other complications of obesity include nephrolithiasis and kidney malignancies. BMI, waist circumference, and weight were positively associated with the development of incident kidney stones [39]. In a retrospective review of 1,698 stone-forming patients, urinary calcium, oxalate, and urate excretion were much higher in overweight and obese patients than in nonobese patients [40]. Higher BMI showed a positive correlation with risk factors for kidney stones, including increased urine sodium and decreased pH in men and increased urine uric acid and sodium and decreased urine citrate in women [41]. Additionally, overweight and obesity increase the risk of renal cancer. Renal cancer is the third highest risk associated with obesity among all cancers [42]. In a population-based cohort study of 5.24 million adults in the United Kingdom, each 1-kg/m2 population-wide increase in BMI was estimated to result in 3,790 additional cases of 1 of 10 cancers (colon, liver, gall bladder, breast, cervix, uterus, ovaries, kidney, thyroid, and leukemia) annually [43]. In particular, the risk of kidney cancer in adults with a 5-fold higher BMI increased by 25%, and excess weight contributed to 10% of all kidney cancers [43]. A recent cohort study of 23.3 million East Asians revealed that the coexistence of general and abdominal obesity increased the risk of kidney cancer by nearly 1.5-fold, compared with nonobese individuals [44]. Table 1 summarizes the renal complications of obesity.

Mechanisms of obesity in kidney disease

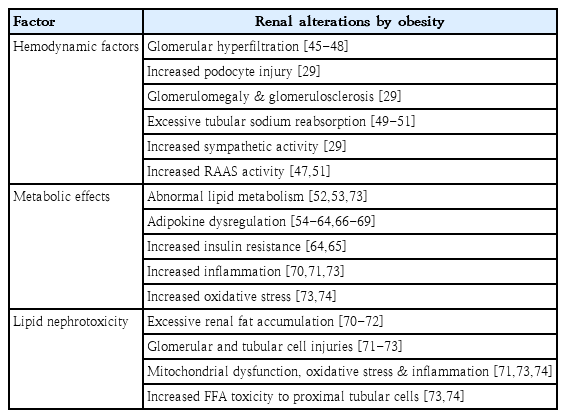

The exact mechanisms underlying the association between obesity and CKD remain unclear. A combination of hemodynamic and metabolic changes and lipid nephrotoxicity (excessive lipid deposition) may cause or aggravate CKD in obese individuals (Table 2).

1. Hemodynamic factors

Renal physiologic response to obesity is mediated via an increase in renal plasma flow, glomerular filtration rate (GFR), filtration fraction, and proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium [29]. Studies on renal hemodynamics have revealed that higher BMI is associated with a greater increase in GFR relative to renal plasma flow and, consequently, a higher filtration fraction [45]. It remains unclear whether elevated GFR at the whole-kidney level reflects glomerular hyperfiltration at the single-nephron level [46]. Nonetheless, it has been hypothesized that glomerular hyperfiltration is a major link between obesity and renal injury [47]. Although the exact concept of glomerular hyperfiltration is uncertain, 2 main mechanisms have been proposed to explain obesity-related renal disease. The first hypothesis proposes that afferent arteriolar vasodilation is the primary event in glomerular hyperfiltration [48]. The vasodilation of renal afferent arterioles and efferent arteriole constriction increase renal plasma flow, glomerular hydrostatic pressure, and single-nephron filtration rate [29]. The second hypothesis states that the increase in the proximal tubular reabsorption of sodium and water is the main contributor to decreased sodium delivery to the macula densa, deactivation of the tubuloglomerular feedback, afferent arteriolar vasodilation, and subsequent glomerular hyperfiltration [49,50]. The increased activation of sodium transporters in the nephron may be involved in increased tubular sodium reabsorption in the kidney of obese patients [51]. In glomerular hyperfiltration, podocytes are exposed to high fluid shear stress, which results in maladaptive podocyte hypertrophy, podocyte detachment, and global glomerulosclerosis [29]. Furthermore, elevated sympathetic activity and the upregulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in obese individuals may play an important role in glomerular hyperfiltration by increasing sodium retention and hypertension [29].

2. Metabolic effects

Obesity leads to metabolic abnormalities. Changes in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism result in dyslipidemia, which contributes to the development and progression of renal disease. Nevertheless, most people who are overweight and obese do not develop CKD, and up to 25% of obese individuals are metabolically healthy, suggesting that weight gain alone may not be enough to trigger the development of kidney diseases [52]. As an endocrine organ, the adipose tissue secretes adipokines, and the altered production of adipokines contributes to complications in obesity [53]. Adipokines are cytokines involved in lipid metabolism, inflammation, immune response, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, metabolic homeostasis, and cell migration and proliferation [54]. These cytokines induce adaptive or maladaptive responses in renal cells against the mechanical forces of glomerular hyperfiltration [53]. Many adipokines, including leptin, adiponectin, vascular endothelial growth factor, angiopoietins, and resistin, play a role in extracellular matrix accumulation, leading to renal fibrosis [55].

The serum levels of the proinflammatory adipokine leptin are approximately 5–10-fold higher in obese individuals than in nonobese individuals [56]. In addition to the control of appetite, energy expenditure, and body weight, leptin affects the immune system and may exacerbate renal dysfunction [57]. Leptin is mainly metabolized in the kidneys by binding to the multiligand endocytic receptor megalin in the proximal tubule [58]. Leptin induces glomerular hypertrophy by stimulating glomerular endothelial and mesangial cell proliferation and directly affects kidney function [59,60]. Additionally, leptin levels are strongly correlated with inflammation and insulin resistance, which are risk factors for the development of CKD [61,62].

The anti-inflammatory adiponectin protects against obesity-associated metabolic complications, including insulin resistance and lipid accumulation [63]. Circulating adiponectin levels are negatively linked with percent body fat, suggesting an inverse correlation between adiponectin and obesity [64,65]. Furthermore, low levels of plasma adiponectin are inversely correlated with proteinuria in obese subjects and can predict adverse renal outcomes in patients with type 2 DM [66,67]. Experimental studies suggest that adiponectin directly affects podocyte function and reduces oxidative stress, decreasing albuminuria [68]. Adiponectin can be a predictor of CKD, and circulating adiponectin levels are negatively linked with estimated GFR [69].

3. Lipid nephrotoxicity

Dysregulated fatty acid and cholesterol metabolism in obesity leads to lipid accumulation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis [29]. Fat accumulation in the kidneys causes structural and functional changes in glomerular and tubular epithelial cells, leading to the development of ORG [70]. Increased triglyceride accumulation in the kidneys was associated with cortical microvascular proliferation, glomerular hyperfiltration, increased proangiogenic and proinflammatory cytokines, and albumin leakage [71]. Notably, the presence of secondary FSGS and glomerulomegaly was related to serum triglycerides and renal lipid deposition but not to the degree of obesity [72]. The increased production of reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and tissue inflammation are important mechanisms underlying damage to podocytes, proximal tubular epithelial cells, and tubulointerstitial tissue by excessive free fatty acids, resulting in glomerular and tubular lesions [73]. In particular, renal proximal tubular cells are known to be more vulnerable to lipid toxicity than other renal cell populations because of higher energy expenditure, which is exclusively mediated via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation [73,74].

Developmental programming of obesity and CKD

In the 1980s, Barker et al. [75] first proposed the fetal origins hypothesis to explain the connection between fetal growth and cardiovascular morbidity. These authors reported that maternal undernutrition during gestation increased the risk of CVD in the offspring later in life. Later studies confirmed the relationship between birth weight and the risk of type 2 DM, hypertension, CVD, and CKD [76-78]. Experimental and clinical studies suggest that maternal obesity increases the risk of premature death and cardiovascular and chronic diseases in the offspring, including obesity, hyperglycemia, and DM [10,11]. Alterations in macronutrient availability, epigenetic modifications, dysregulated adipokine production, and inflammation are the primary mechanisms underlying developmental programming of obesity [79]. Emerging evidence suggests that fetal exposure to maternal obesity increases the risk of developing CKD later in life, indicating that intrauterine exposure to maternal obesity is a significant risk factor for CKD [12]. In rodent models of maternal obesity, offspring of obese mothers had albuminuria, renal pathology, increased fat deposition, impaired glucose tolerance, and insulin resistance [12,80,81]. The renal effects of maternal obesity related to oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis persisted until adolescence in the offspring of obese mothers [12]. In addition, clinical studies have demonstrated that maternal DM or obesity predisposes offspring to hypertension, renal hyperfiltration, and CKD [82,83]. A population-based study involving 1,994 children with CKD found that low birth weight, pregestational and gestational DM, and maternal overweight and obesity increased the risk of childhood CK.D [83] Exposure to maternal overweight and obesity increased the risk of CKD by 24% and 26%, respectively, compared with controls [83]. Obese mothers, independent of the presence of DM, showed a higher risk of bearing children with CKD due to obstructive uropathy than nonobese mothers [83]. These findings imply that maternal obesity impairs renal development and increases the risk of CKD in offspring [84]. Potential mechanisms underlying this effect include autophagy, inflammation, oxidative stress, and epigenetic regulation [85]. Environmental factors aggravate renal damage in offspring born to obese mothers. Obesity and other comorbid conditions in offspring exacerbate the deleterious effects of maternal obesity on children’s kidney health [85]. Early life risk factors, such as intrauterine growth restriction, low and high birth weight, low nephron number, drug use, and rapid postnatal growth, are also linked to developmental programming of renal function (Fig. 1) [86,87].

Management

While genetic, metabolic, and environmental factors are implicated in the development of obesity, obesity may be a modifiable lifestyle risk factor for the progression of CKD. Hence, weight reduction through dietary management and increased physical activity remain the cornerstone of obesity treatment [88]. In overweight or obese people with type 2 DM, intensive lifestyle interventions diminished the risk of CKD by 31% compared with DM management and education [89]. A systematic review involving obese patients with altered renal function demonstrated that intentional weight loss consistently decreased blood pressure, hyperfiltration, and proteinuria [90]. Physical exercise combined with optimization of the metabolic and nutritional status is crucial in the management of patients with CKD [91]. In addition, treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors decreases proteinuria and the risk of renal disease progression in obese individuals [88,92]. The renoprotective effect of these drugs in proteinuric patients with CKD was more pronounced in obese patients with CKD than in overweight or normal BMI patients [92]. Dyslipidemia treatment together with the limited intake of saturated fat and cholesterol is also important in children with CKD [88]. However, treating children and adolescents with lipidlowering drugs is controversial: some guidelines do not advocate the use of statins in children with CKD, and other guidelines recommend statins to children aged 10–21 years with continuously increased levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol after dietary management for 6 months [93,94]. Notably, bariatric surgery has been performed in severely obese patients (BMI≥35 kg/m2) and significantly improved GFR in patients with advanced CKD for up to 3 years [95,96]. Evidence-based best practice guidelines recommend weight loss surgery for adolescents with extreme obesity and other severe comorbidities [97]. In severely obese adolescents with decreased renal function at baseline, the mean estimated GFR following bariatric surgery increased from 76 to 102 mL/min/1.73 m2 at 3-year follow-up [98]. Albuminuria significantly improved after surgery in patients with increased albuminuria at baseline [98]. Long-term cohort studies and randomized clinical trials reported that bariatric surgery prevented the development and progression of CKD and improved weight reduction, blood pressure, and metabolic control [99]. Pharmacotherapy can be used as a component of a comprehensive strategy for managing patients with severe obesity and obesity-related comorbidities. However, the effectiveness of this therapy for obesity-related comorbidities are limited [6,100]. The major antiobesity medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration include orlistat (pancreatic and gastric lipase inhibitor), phentermine (sympathomimetic amine), lorcaserin (selective serotonin receptor agonist), phentermine/topiramate (sympathomimetic amine anorectic agent/antiepileptic drug), naltrexone/bupropion (opioid antagonist/aminoketone antidepressant), and liraglutide (a glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist) [100]. Orlistat and phentermine are approved for treating obesity in adolescents [101]. Orlistat can be prescribed to adolescents aged ≥12years for long-term management of obesity. This drug reduces fatty acid absorption by the intestinal endothelium through inhibiting gastrointestinal and pancreatic lipases [102]. Phentermine is an amphetamine analog that can be prescribed to adolescents aged >16years for short-term treatment of obesity [101]. This drug works as an appetite suppressant by increasing catecholamine and serotonin activity in the central nervous system [100,101]. However, evidence to support the use of antiobesity drugs in children and adolescents is currently limited, and a multilevel approach is needed to prevent obesity and related chronic diseases. Early lifestyle interventions, including exercise and dietary changes, should be the first-line approach for preventing and treating obesity.

Conclusion

Obesity is strongly associated with the development and progression of kidney diseases. Obesity increases the risk of CKD, hypertension, and DM in children and adolescents and the risk of mortality in children with ESRD. Maternal obesity predisposes offspring to CKD and obesity, indicating that intrauterine exposure to maternal obesity is an important risk factor for developing CKD. Therefore, pediatricians should acknowledge the long-term effects of maternal obesity on renal outcomes in children. Weight loss due to increased physical activity and caloric restriction should be considered the first-line therapy for treating obesity in children and adolescents. Lifestyle modifications can improve several risk factors simultaneously and reduce the risk of CKD. The development of evidence-based interventions is necessary to halt the intergenerational transmission of obesity and related chronic diseases.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.