Modified high-flow nasal cannula for children with respiratory distress

Article information

Abstract

Background

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is a noninvasive respiratory support that provides the optimum flow of an air-oxygen mixture. Several studies demonstrated its usefulness and good safety profile for treating pediatric respiratory distress patients. However, the cost of the commercial HFNC is high; therefore, the modified high-flow nasal cannula was developed.

Purpose

This study aimed to compare the effectiveness, safety, and nurses’ satisfaction of the modified system versus the standard commercial HFNC.

Methods

This prospective comparative study was performed in a tertiary care hospital. We recruited children aged 1 month to 5 years who developed acute respiratory distress and were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit. Patients were assigned to 2 groups (modified vs. commercial). The effectiveness and safety assessments included vital signs, respiratory scores, intubation rate, adverse events, and nurses’ satisfaction.

Results

A total of 74 patients were treated with HFNC. Thirty-nine patients were assigned to the modified group, while the remaining 35 patients were in the commercial group. Intubation rate and adverse events did not differ significantly between the 2 groups. However, the commercial group had higher nurses’ satisfaction scores than the modified group.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that our low-cost modified HFNC could be a useful respiratory support option for younger children with acute respiratory distress, especially in hospital settings with financial constraints.

Key message

Question: Can the modified high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) provide alternative respiratory support for children with acute respiratory distress?

Finding: A total of 74 patients were assigned to the modified or commercial HFNC groups. The intubation rate, length of hospital stay, and adverse events did not differ between the 2 groups.

Meaning: The modified HFNC can provide alternative respiratory support for pediatric respiratory distress.

Graphical abstract. Comparison of the modified and commercial high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) systems.

Introduction

High-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) is noninvasive respiratory support that provides optimum flow of heated, humidified, and air-oxygen mixture to patients via a nasal cannula interface. The traditional nasal cannula uses a flow rate of fewer than 4 L per minute (L/min) and is associated with drying of the airway mucosa and discomfort [1]. The optimal flow rate is unknown, but it is adjusted individually to minimize the patients’ work of breathing. High flow is usually defined as flow rate varied from 2–8 L/min in infants and range up to 60 L/min in adolescents and adults. It supplies adequate warmed and humidified gas that decreases pulmonary conductance [2-4]. The mechanisms of HFNC include washout of nasopharyngeal dead space, facilitated secretion removal, decreased inspiratory resistance, increased pulmonary compliance, and decreased work of breathing [5,6]. Many studies indicated HFNC is useful in pediatric respiratory distress patients with good safety profiles [6-9]. A recent study with large randomized controlled trial of HFNC in infants with bronchiolitis showed HFNC had significantly lower rate of treatment failure when compared with standard oxygen therapy [10]. However, some studies reported mild to severe adverse effects which included epistaxis, abdominal distention, and air leak syndrome [7,11]. The commercial HFNC (AIRVO II, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare, Auckland, New Zealand) is used worldwide in hospitals. However, its cost is relatively high for routine use in developing countries and most patients cannot afford this device. Therefore, our center has developed a modified HFNC since 2011 that costs of approximately one-third of the commercial HFNC. Our recent retrospective study showed the modified HFNC was useful respiratory support in young children with community-acquired pneumonia [12]. The aim of this study was to compare the effectiveness and safety of the commercial and modified HFNC in children with respiratory distress.

Methods

We performed a single-center, prospective comparative study conducted in total 17-bed multidisciplinary medical-surgical pediatric intensive care unit and intermediate ward in our hospital from February 2017 to February 2018. Our institute is a regional referral center for pediatric subspecialty care in Thailand. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University Faculty of Medicine (IRB number; MURA2016/575), and informed consent was obtained. Eligible subjects included all patients aged 1 month to 5 years old who developed respiratory distress and required HFNC. Patients who had facial anomaly, tracheostomy, respiratory failure, or do-not-resuscitate status were excluded from this study. Participants were assigned to either the modified group (using modified HFNC) and the commercial group (using AIRVO II). We collected demographic data, vital signs, the modified respiratory score, complications, length of hospital stay, and intubation in both groups.

1. Study protocol

Eligible patients with parental consent were included. All patients’ nostrils were cleaned by normal saline and nasal decongestant before the application of HFNC. Due to the inadequate availability of the commercial HFNC during the initial phase for 2 months (from February to April 2017), the patients who were admitted during this period were allocated to the modified HFNC group. Once the commercial HFNC was readily available, the allocation was made using 1:1 alternate allocation into each group based on the admitting diagnosis. The analysis was performed strictly per protocol and no cross-over was allowed. The nasal cannula size was used as per the current manufacturer’s instructions in the commercial group, while the modified group used nasal cannula size approximately 50%–70% fit to the patient’s nostrils for allowing leakage of excessive flow. The humidifier was auto set to 37°C. The modified HFNC device includes oxygen and air pipelines, a heated humidifier (MR850, Fisher & Paykel Healthcare), a single-heated breathing circuit, and standard oxygen nasal cannula as shown in Fig. 1. The modified respiratory clinical score (MRCS) was used to assess the severity of respiratory distress. The components included 4 parameters (respiratory rate scale, 1–3; retractions, dyspnea, and wheezing scale, 0–3). The maximum for this score was 12 [13,14]. The initial flow rate of HFNC was adjusted by patient’s age: 1–6 months, 4–8 L/min; 6–18 months, 4–12 L/min; 18–60 months, 8–15 L/min; and maximal initial flow rate did not exceed 2 L/kg/min with FiO2 40% [15]. Flow rate was increased to 2–3 L/kg/min or maximum 20 L/min and/or increased FiO2 to 50% after 15 minutes if there was no clinical improvement or the MRCS was higher than 3. We measured the vital signs, oxygen saturation, and the MRCS at initial, 1, 4, 12, 24, and 48 hours. Other respiratory care and nursing care were similar in both groups. When the patient was clinically stable, FiO2 was weaned to 40% then flow rate of HFNC was reduced 2–4 L/min every 2 hours until flow rate of 4–6 L/min was achieved.

Drawing of the modified high-flow nasal cannula system. (1) Oxygen and air flow meter. (2) Y-connector. (3) Endotracheal tube connector. (4) Heated humidified. (5) Heated inspiratory circuit. (6) Nasal cannula.

Nurses’ satisfaction in using these 2 systems’ devices were assessed and filled-in in Likert scale (from “1=completely disagree” to “5=in total agreement”) with 6 topics including endurance of equipment, easy to assemble, easy to use, patient comfort, noise, and easy to clean.

2. Definitions

Indications for using HFNC were children who had respiratory distress and failed to respond to low flow nasal cannula.

The intubation criteria were defined as persistent respiratory acidosis (arterial pH <7.35 with PaCO2 >45 mmHg) after using HFNC for at least 2 hours, persistent hypoxemia (SpO2 <90 or PaO2 <60 mmHg during treatment with FiO2 >50%), or had clinical signs of acute respiratory failure (respiratory rate >2 standard deviation for age, increased respiratory effort such as accessory muscle use, intercostal retraction, or paradoxical motion of the abdomen) [16].

The definition of respiratory distress was defined as patients who were receiving low flow nasal cannula and had signs of respiratory distress, including an increase in respiratory rate, dyspnea, grunting, nasal flaring, or chest retraction.

3. Study outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who required endotracheal tube intubation. The secondary outcomes were the length of hospital stay, vital signs, the MRCS, and complications related to HFNC.

4. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 20.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were presented as the mean and standard deviation, median and interquartile range were reported. The comparison of data between the 2 groups used chi-square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. The Student t test was used for continuous data with normal distribution or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data without normal distribution. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

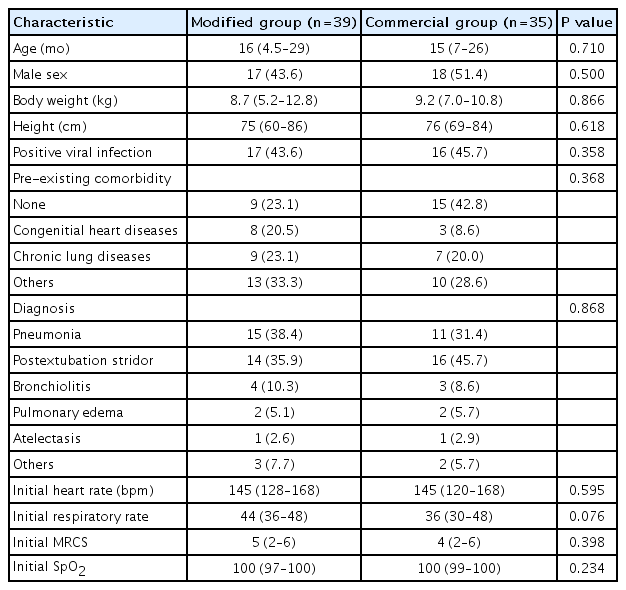

Altogether 123 respiratory distress patients were screened. Forty-nine patients were excluded as in Fig. 2. A total of 74 children met the inclusion criteria and were commenced on HFNC therapy. The median age was 16 months (interquartile range [IQR], 6–26), and 35 males (47.3%) were enrolled. Thirty-nine patients were assigned into the modified group, while the remaining 35 patients were in the commercial group. The baseline characteristics were not significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 1).

There were 12 patients (16.2%) who needed the escalating respiratory support after using HFNC which included 1 patient who used noninvasive positive pressure ventilation and the remaining patients required intubation. The overall intubation rate was 14.8%. Four out of 39 patients (10.2%) in the modified group and 7 out of 35 patients (20.0%) in the commercial group (P=0.330) required intubation which occurred within 48 hours after use of HFNC. All patients discharged home safely. The median lengths of hospital stay were 15 (IQR, 8–39) and 17 days (IQR, 9–42) in the modified and commercial groups, respectively (P=0.645) as shown in Table 2. Patients in both groups showed improvement in heart rate, respiratory rate, and the MRCS after enrollment (Fig. 3), and the changes of heart rate, respiratory rate, and the MRCS were not significantly different between the 2 groups. The flow rate of HFNC per patient’s weight in the modified group was statistically significantly lower than the commercial group at initial, 4 hours, 12 hours, 24, and 48 hours as shown in Fig. 4. There were some minor adverse events in both groups such as nasal redness, epistaxis, bloating, vomiting, but no statistical difference between the groups (P=0.386) as shown in Table 2. No serious adverse events occurred in this study. The nurses’ satisfaction was collected from 69 nurses during this study. The commercial HFNC had significantly more satisfaction than the modified HFNC in terms of easy to assemble, easy to use, patient comfort, and noise (P<0.05) as shown in Table 2. As the heterogenesity of cause of intubation, we had post hoc analysis without patients who had postextubation stridor. There were 44 patients, 25 patients in the modified group, and 19 patients in the commercial group. The baseline characteristic were not different between the 2 groups. Three out of 25 patients (12%) in the modified group and 3 out of 19 patients (15.8%) in the commercial group (P=0.717) required intubation which occurred within 48 hours after use of HFNC. The length of hospital stay, duration of HFNC, and adverse events were not different between the 2 groups.

Clinical outcomes, complications, and nurses’ satisfaction scores of modified versus commercial HFNC systems

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the effectiveness and safety of our modified HFNC compared to the commercial HFNC in pediatric patients with respiratory distress. Our data suggest that modified HFNC might be effective and safe to be used in hospitalized pediatric patients as an alternative respiratory support. To our knowledge, this study is the first comparative study of the modified HFNC with the commercial HFNC for pediatric respiratory distress in resource-limited hospital settings. We had the experimental study prior this study by using the nasal model and measured the upper airway pressure with the different flow from 3 L/min then upto 25 L/min on the modified HFNC and commercial HFNC. The upper airway pressure was between 1.4–7.5 cmH2O on both machines. Before this study, we had measured the pharyngeal airway pressure on the modified HFNC in 3 young bronchiolitis children with mouth closure. The pharyngeal pressure with flow 1 L/kg/min and 1.5 L/kg/min were 1–2.7 and 1.4–4 cmH2O, respectively. This result was similar with the previous study [17].

Previous studies showed the intubation rate in patients with acute bronchiolitis, respiratory distress, or postextubation stridor patients varied from 7%–40% [18-21]. The intubation rate in bronchiolitis patients with HFNC therapy was lower than others diseases [10,18,19]. The intubation rate in this study was 14.8%. The 2 most common conditions requiring HFNC in this study were pneumonia and postextubation stridor (56 of 74 patients, 75.7%). Although the intubation rate of the modified group was approximately half of the commercial group, the difference did not reach statistical significance, probably due to small sample size. Other clinical outcomes were not different between the 2 groups. Both the modified and commercial HFNC had comparable beneficial effect on improving heart rate, and MRCS. The adverse events were not different between the 2 groups.

The nurses preferred to use the commercial HFNC because it was easy to assemble, and easy to use. However, the cost of modified HFNC is much lower than the commercial HFNC. The costs for the commercial HFNC machine and its disposable set is 7,100 and 190 United States dollar (USD), respectively, while those of the modified HFNC is 2,500 and 25 USD (calculated by 1 USD=32 Thai baht). The limitations of the modified HFNC are this system requires the oxygen and air pipeline for the source of flow, and it can be used only in hospital setting. In addition, the maximal flow rate of the modified HFNC is limited up to 20 L/min because the connection system burst and broke when the flow rate was higher than 20 L/min. Therefore, it cannot be used in older children who need higher flow rate.

This study has some limitations. This was a prospective comparative single-center study with a relatively small sample size. We planed to do the randomized controlled trial study at the beginning of the study, but it was not practical due to limited availability of the commercial HFNC machine during the study period. This might cause selection bias. We minimized this potential bias by using the stratification by patients’ diagnosis and strictly followed the study protocol in both groups. In the further study, the randomized controlled trial will be conducted.

In conclusion, we suggest that the modified HFNC could be an alternative respiratory support for children with acute respiratory distress in limited-resourced hospital setting.

Notes

Funding

The author(s) received financial support for the research from Ramathibodi Research Fund.

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all colleagues in Pediatric Critical Care and Pulmonary Division, the Department of Pediatrics Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University. We would also like to thank Prof. Pat Mahachoklertwattana for the critical review of the article and Dr. Jeeraparn Phosuwattanakul for drawing the modified high-flow nasal cannula picture. We would like to thank Mr. Stephen Pinder for grammar correction. Furthermore, our special thanks to all patients who participated in this study.