Jeopardized mental health of children and adolescents in coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

Article information

Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak became a worldwide pandemic in 2020. Social distancing measures, such as self-quarantine, lockdowns, and school closures, which have proven efficacy in various pandemic situations, remain in use in Korea. These measures prevented viral transmission to some extent; however, adverse effects have also resulted. First, the negative effect of social isolation on mental health is evident. This influences the psychiatric milieu of parents and children directly and indirectly. The most stressful factor among Korean youth was the restriction of outdoor activities. Increasing parenting burden result in increased screen time among youth, and social isolation created depressive mood with symptoms similar to those of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and anxiety. Second, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and somatization are prevalent among children and adolescents. The sense of threatened health and life during the pandemic, one symptom of PTSD, is a strong risk factor for somatization. Finally, the increased pattern of child abuse in pandemic indicates increased levels of emotional/psychological abuse and nonmedical neglect. Social isolation makes people less aware of these events. Because pediatricians evaluate pediatric patients and their families, they should regularly assess emotional/stress factors, especially when somatization is prominent during the pandemic, and cautiously recommend that families seek advice from mental health professionals when warranted. Primary physicians must understand the characteristics and aspects of child abuse in the COVID-19 pandemic, make efforts to identify signs of child abuse, and deliver accurate information and preventive strategies for child abuse to caregivers, thereby functioning as a professional guardian. To promote the mental health of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic, more research and cooperation among health professionals, families, governments, and schools are needed in the future.

Key message

· The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has required preventive measures like self-quarantine, school closures, and lockdown, which ultimately make youth directly and indirectly vulnerable to depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and somatization.

· Child abuse is more common in the COVID-19 era than previously.

· Pediatricians should carefully examine parental and child mental health to directly and indirectly aid their physical and mental health.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which was first reported as an infectious acute respiratory disease in Wuhan, China, in 2019, has rapidly spread worldwide. Although severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreaks occurred in 2003 and 2013, respectively, they differed from COVID-19 in terms of infectivity. These viruses are typically contagious when an individual is symptomatic; thus, the spread rates in the community were low. In contrast, COVID-19 is highly contagious, even during symptom-free periods. This characteristic led to the COVID-19 pandemic and, ultimately, the “new normal” era that ultimately changed the daily life of humankind. Since social distancing methods such as self-quarantining, lockdowns, and school closures were effective in previous pandemic situations, many countries worldwide have implemented them during the COVID-19 pandemic [1].

In the South Korean guidelines for disease prevention published in 2020 [2], during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevention measure focused primarily on physical social distancing was adapted to immune-deprived adults and admitted patients in psychiatric hospitals and nursing hospitals who were at high risk of cluster infection [3]. At that point, little attention was paid to the psychological aspect of children and adolescents, particularly due to isolation from their daily social activities, peers, and teachers due to school closures. Wearing masks prevents children and adolescents from having the natural opportunity to experience and learn non-verbal communication with others in society. As reported by numerous studies, the socioeconomical, psychological, and physical aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic have been devastating on the development of children and adolescents [4]. Their cognitive development in particular was negatively affected, and their coping strategies are incomplete and emotionally immature. These features of young people make them vulnerable to stressful factors during disasters despite still experiencing critical developmental tasks. During that time, they develop their basic attitudes toward life by interacting with other people and diverse environments; these experiences give them resilience to inevitable stressful life events. Therefore, youths are especially vulnerable in disasters such as COVID-19 because high anxiety impairs their ability to learn.

A large number of psychiatric studies of the mental health of children and adolescents in this pandemic era have been published in the United States and China [4,5]. However, few of the same have been published in South Korea. The South Korean government recently aimed to expand the mental health factual survey for adults to include children and adolescents. This trial reflects the government’s concern about the mental health of those vulnerable age group.

This study aimed to review various studies of the mental health of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic including the domain of child abuse in an effort to provide direction for their further management.

Effect of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health of children and adolescents

Previous studies of the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children and adolescents reported increased depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic symptoms [3,4]. One study reported that parental unemployment and financial difficulties are clearly associated with their children’s emotional problems [6]. In other studies, excessive smartphone use and increased internet addictions due to increased isolation among youth were associated with depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic [5,7].

The supervision and care of youth have been compromised during the COVID-19 pandemic. To prevent its transmission throughout the community, self-quarantine and school closures were implemented. These actions resulted in children being left alone at home without proper caregiving, especially those in double-income families. The increased burden of childrearing leads to parental permission for their children to use digital media, even when the parents are at home. In fact, the mean screen time of children and adolescents since the COVID-19 outbreak (3.96±2.28 hours per day) is significantly higher than that before the outbreak (2.2±1.84 hours per day) [8]. The recommended media exposure time is below 2 hours per day [9]. In a previous study, a screen time longer than 2 hours per day increased depression and suicidal ideation in children and adolescents. Depression among children and adolescents was reportedly increased according to many studies since the COVID-19 outbreak, consistent with another previous study [10,11]. This is a problematic phenomenon, especially in 3–5-yearold children in South Korea because 2.5% of that age group was already at high risk of smartphone dependency and 11.4% were at potential risk before the pandemic [12].

Moreover, sleep problems due to increased screen time exacerbate children’s negative emotions [13]. A previous study suggested that the electromagnetic fields generated by mobile phones were associated with less favorable sleep duration, nocturnal awakening, and parasomnia in 7-year-old children [14]. Furthermore, increased screen time also causes symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which increases parenting burden [15,16]. These ADHD similar symptoms results in a vicious cycle through negative feedback from parents to their children that worsen children’s depression and anxiety symptoms.

In one study of the effect of COVID-19 on stress in children and adolescents in South Korea, the most stressful factor among youth was the restriction of outdoor activities, such as inability to meet friends and stay at home orders. The second most stressful factor was difficulty understanding lecture content through online classes [17]. As a result, children who perceived this kind of stress showed more intense emotional difficulties. They were also more susceptible to depressive mood, anxiety symptoms, more aggressive behavior, and greater dependency on smartphones; all of these effects negatively correlated with academic difficulties that ended up lowering self-esteem among children and adolescents [17]. On the contrary, some positive reports stated that more time spent at home with their parents prevented children and adolescents from suicidal attempt and substance use disorders, although further long-term studies are needed [18].

Some studies revealed that older adolescents show more depressive symptoms than younger adolescents and children [19]. However, the existence of differences in anxiety symptoms by age remains controversial. While 2 studies reported no difference in anxiety symptoms by age [19,20], another reported that anxiety symptoms increased with increasing age [21].

Relationship between children’s negative emotions and posttraumatic stress disorder in the COVID-19 pandemic

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [22], “experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic events” is a potential traumatic event. Accordingly, the COVID-19 pandemic can be defined as a traumatic disaster [23]. Like sudden acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome, COVID-19 causes posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms in healthcare workers such as intrusive thoughts associated with traumatic memory, persistent avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal [24,25]. Similarly, children and adolescents also suffer from PTSD symptoms in this pandemic situation. Recent research revealed that the prevalence of PTSD among 57,948 high school students after COVID-19 outbreak peaked at 16.9% and emphasized the long-term adverse consequences on their mental health [26]. It is also suggested that COVID- 19 pandemic itself functions as a big traumatic event to youth, causing PTSD symptoms and in turn increasing their depressive symptoms.

Because somatization is one of most prevalent symptoms in children and adolescents with mental health issues, it also should be spotlighted. Somatization is simply defined as a persistent somatic symptom with no evident organic cause even after a thorough medical evaluation. Symptoms can vary but include dizziness, pain, fatigue, and musculoskeletal manifestations [27,28]. Depressed youths often complain of somatic symptoms such as headaches and stomachaches; this is a unique feature of children versus adults with depression [29,30]. As mentioned above, children and adolescents with limited ability to recognize their emotions frequently experience negative emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic, which in turn causes somatic symptoms that negatively affect their physical and psychological well-being. Therefore, pediatricians have increased opportunities to evaluate youth in the clinic settings; moreover, it is recommended that emotional and stressful factors be addressed and evaluated by pediatricians in primary pediatric clinic settings during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In one cross-sectional study of primary school students during the early COVID-19 pandemic in China, children were asked to complete self-questionnaires of their somatization symptoms and concerns about COVID-19 [31]. In that study, primary school students with somatization symptoms reported a higher threat to their lives and health, which in turn was revealed as a strong risk factor for somatization. Interestingly, anxiety, not depression, was associated with somatization. Jowett et al. [32] suggested that the sense of threat, among the PTSD symptom cluster of the International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Edition, also showed a strong association with somatization in adults.

In previous studies, the lower the resilience, the greater the degree of somatization. Resilience is defined as an ability to recover from stress [33,34]. Shangguan et al. [35] reported that lower resilience is a predictor of somatization, while perceived stress acts as a moderator of resilience and somatization. Perceived stress is more intense and more prevalent among women than among men, revealing a sex-based difference. Therefore, interventions that improve resilience would decrease somatization [36-38]. This is expected to be more beneficial for youths and their caretakers, mostly women, in Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic, but further investigations are required.

COVID-19 pandemic and child abuse inside the family

It is essential to address child abuse issues in the COVID-19 pandemic. Child abuse is a huge traumatic experience to developing young minds that negatively affects an individual’s emotional and physical well-being throughout the lifespan. Social isolation in the COVID-19 pandemic is a well-known risk factor of child abuse [39,40]. Most child abuse occurs at home by parents, with whom social isolation due to COVID-19 puts children in closer contact, who are nervous and edgy because of social and financial distress [41]. This situation of home lockdown increases the likelihood of child abuse. Brown et al. suggested that parental situations including needing financial help, depression, and anxiety are strongly associated with the likelihood of child abuse [42]. Likewise, Lawson et al. [43] reported that parental unemployment is risk factor of both psychological and physical child abuse.

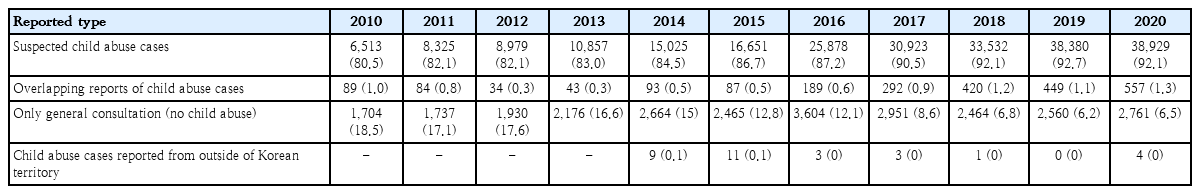

In 2020, Ministry of Health and Welfare of South Korea published a document entitled “Major Statistic Data of Child Abuse,” which reported a 2.1% increase in child abuse reporting compared to the 13.7% rate of 2019 [41]. Also, 92.1% of child abuse cases were reported in 2020 versus 92.7% in 2019 (Table 1, Fig. 1) [41,44]. In South Korea, among mandatory child abuse reporters, employees of primary, middle, and high schools showed the highest reporting rate (Table 2; Figs. 2, 3). However, reported cases by primary, middle, and high school employees decreased from 5,901 cases in 2019 to 3,805 cases in 2020 [41]. Online classes due to school closure in 2020 hindered teachers from observing their students directly and talking face to face with them. Although the COVID-19 pandemic is a period of a high likelihood of child abuse, teachers have difficulty noticing abuse clues among their students due to physical and temporal obstructions. On the contrary, cases reported to Child Protective Services (CPS), public officers, and child welfare workers were greatly increased. Reports by healthcare providers and physicians were also slightly increased from 293 cases in 2019 to 363 cases in 2020 [41]. It is encouraging that reports by healthcare providers and physicians were increased since it implies that the role of reporting child abuse by police officers, physicians, and CPS has become more important since the COVID-19 outbreak. These professionals are recommended to have increased knowledge and more intent to detect child abuse. However, this will be possible only with the provision of greater governmental support.

In addition, the pattern of child abuse in COVID-19 pandemic differs from that of pre-COVID-19 era. In the COVID-19 pandemic, emotional/psychological abuse and nonmedical neglect (any neglect that is not related with the child’s medical needs) are significantly increased [45]. Because of this changed pattern of abuse, it is seldom identified by surrounding people and might mitigate the increasing rate of case reporting of child abuse. Another difference in the COVID-19 pandemic is increased children’s self-reporting of abuse [41].

Management to improve mental health of children and adolescents

The COVID-19 pandemic created physical, social, emotional crises for many children and adolescents (Table 3). They are now more likely to experience depression and anxiety and are at greater risk of emotional disturbances during adolescence and adulthood, particularly those with less educated parents, fewer friends, and less physical activity [20]. Among these risk factors, physical activity can be modified. Rothon et al. [46] revealed that increasing physical activity by 1 hour per week was associated with an 8% decrease in the odds of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Also, a meta-analysis suggested that increased physical activity in youth is associated with decreased depressive symptoms [47]. Moreover, the number of obese children has increased due to reduced physical activity since the COVID-19 outbreak, which threatens their physical health [48]. Hence, in clinical settings, professionals who can directly assess a child’s physical health, such as a pediatrician, should educate parents and youths to increase their physical activity to improve their emotional and physical well-being and evaluate whether a child is performing adequate physical activity by referring to the 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines [49,50].

Pediatricians should carefully pay attention to the burden of childcare and social and financial issues of caregivers and evaluate their mental health state using the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9, a short and validated self-reported screening tool for major depressive disorder with a sensitivity of 86.5% and specificity of 52.9% [51]. If the total score exceeds 10, a pediatrician should actively connect them with mental health professionals to ensure proper treatment for their depression. This ultimately promotes the mental health of their children and adolescents and helps decrease their screen time by decreasing the subjective parental burden at home. Likewise, pediatricians should assess their psychosocial problems, including behavioral and emotional problems, using the Korean version of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist, a simple and useful screening tool for children 7–18 years of age. If the total score exceeds 14 (sensitivity, 91.8%; specificity, 89.9%) [52], pediatricians should refer them to child psychiatrists.

In the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation and school closures prevent the proper surveillance of youth by others. Therefore, child abuse cases might be underdetected and occur secretly behind closed doors. Moreover, the pattern of child abuse in the COVID-19 pandemic mainly involves emotional/psychological and nonmedical neglect. Primary physicians who can directly evaluate children and adolescents, such as pediatricians, are among the few important person who can be aware of childhood abuse. Hence, pediatricians must understand the characteristics and aspects of child abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic and aim to identify signs of child abuse, thereby functioning as a professional guardian [53].

Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, children and adolescents feel threats to their lives and health or concern about being infected or passing viruses to others, which can cause somatization. Thus, providing accurate information, prevention guidelines, and mental health referrals is very important to preventing somatization in children and adolescents. Together, when children and adolescents finally return to school after any period of lockdown, it is important to remember that they already have experienced much adversity, which may result in PTSD. Thus, physicians, teachers, and parents should be told that they definitely need more time to adjust than usual and helped in many directions. Previous research suggested a cooperative model to overcome the COVID-19 pandemic [54]. This model suggested that psychological service should be provided to the social, school, and family systems; this approach is important to solving the psychological problems of children and adolescents. Since the physical health of children and adolescents is reciprocal and inseparable from their mental health, pediatricians should routinely evaluate the emotional state of children and adolescents and help at-risk children obtain proper attention and help from mental health professionals.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic enormously changed the daily lives of humankind by restricting social contacts and increasing depression, anxiety, and somatization. It also increased the screen time of children and adolescents. All of these factors jeopardize youth since they are still making crucial developmental steps and are vulnerable to adversity. This is a direct and negative effect of COVID-19 pandemic, but indirect effects also play a role, including increased parenting burden, parental unemployment, financial struggles, less supervision, more time alone, more familial conflicts, and a higher risk of child abuse. Therefore, primary physicians should pay more attention to these issues and assess their patients’ mental and physical health. In the continuing COVID-19 pandemic, pediatricians are becoming more important and function as professional guardians. More research should be done to promote an evidence-based approach and government policy should help the family, school, and social systems cooperate to protect the mental health of children and adolescents.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article was reported.