Treatment of congenital cytomegalovirus infection

Article information

Abstract

Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common cause of congenital infection worldwide, the most common nongenetic cause of sensorineural hearing loss in children, and a cause of neurodevelopmental disorders in the brain. Infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infection may benefit from hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes, particularly if antiviral treatment is initiated within the first month of life. Infants with life-threatening symptoms are recommended to receive 2–6 weeks of intravenous ganciclovir and then switch to oral valganciclovir, and those without life-threatening symptoms are recommended to use oral valganciclovir during the entire 6-month period. During antiviral drug treatment, absolute neutrophil count, platelet count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and liver function tests were performed to identify neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, renal failure, and liver failure. This review investigated the evidence to date of treating congenital CMV infection.

Key message

· Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is among the most common causes of nongenetic sensorineural hearing loss.

· Congenital CMV is initially treated with intravenous ganciclovir for 2–6 weeks and switched to oral valganciclovir, or with oral valganciclovir for the entire 6-month period.

· Infants with congenital CMV require periodic monitoring of absolute neutrophil count, platelet count, and blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function tests, audiological, ophthalmological, and developmental tests during antiviral medication.

Graphical abstract. Overview of the management of congenital cytomegalovirus infection. CMV, congenital cytomegalovirus; cCMV, congenital CMV; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss; CBC, complete blood count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; PC, platelet count; LFT, liver function test; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine transaminase; TB, total bilirubin; DB, direct bilirubin; RFT, renal function test; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; VGCV, valganciclovir; BID, twice a day; IV, intravenous; GCV, ganciclovir.

Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (CMV), which belongs to the Herpesviridae family and is the most common cause of congenital infection, has a prevalence of 0.2%–6%, even in developed countries [1]. Congenital CMV infection can cause neurodevelopmental disorders, such as cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, visual impairment, and seizures, and is the main cause of nonhereditary sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) [2]. Antiviral treatment for congenital CMV infection began with ganciclovir 30 years ago, with oral valganciclovir being the most commonly used [3]. However, due to toxicity, these drugs should be used only when necessary after a thorough benefit–risk evaluation in infants with congenital CMV infection. Although treatment is essential for symptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection, that for infants with only isolated SNHL or asymptomatic disease is controversial [2]. This review aimed to examine studies of congenital CMV infection and determine when and how to treat infected patients.

Diagnosis and classification

Congenital CMV infection can be diagnosed by detecting CMV DNA in the newborn’s urine, saliva, or blood within 3 weeks of birth [3-11]. However, it cannot be diagnosed by the detection of CMV antibodies, nor can it be detected in samples collected more 3 weeks after birth because testing after this time cannot distinguish among congenital, perinatal, and postnatal infections [2,5,7].

Congenital CMV infection can be classified as moderately to severely symptomatic, mildly symptomatic, asymptomatic with isolates of SNHL, or asymptomatic. Moderately to severely symptomatic congenital CMV infection is defined as multiple manifestations (thrombocytopenia, petechiae, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, intrauterine growth restriction, hepatitis) or central nervous system (CNS) involvement, such as microcephaly, radiographic abnormalities consistent with CMV CNS disease (ventriculomegaly, intracerebral calcifications, periventricular echogenicity, cortical or cerebellar malformations), abnormal cerebrospinal fluid indices for age, chorioretinitis, SNHL, or detection of CMV DNA in the cerebrospinal fluid. Mildly symptomatic congenital CMV infection is defined as infection with 1 or 2 isolated manifestations of congenital CMV infection, such as mild hepatomegaly, a single low platelet count measurement, or elevated alanine aminotransferase levels. Asymptomatic congenital CMV infection with isolated SNHL is defined as no apparent abnormalities suggestive of congenital CMV infection. Asymptomatic congenital CMV infection is defined as an infection with no apparent abnormalities suggestive of congenital CMV infection and normal hearing [5,12].

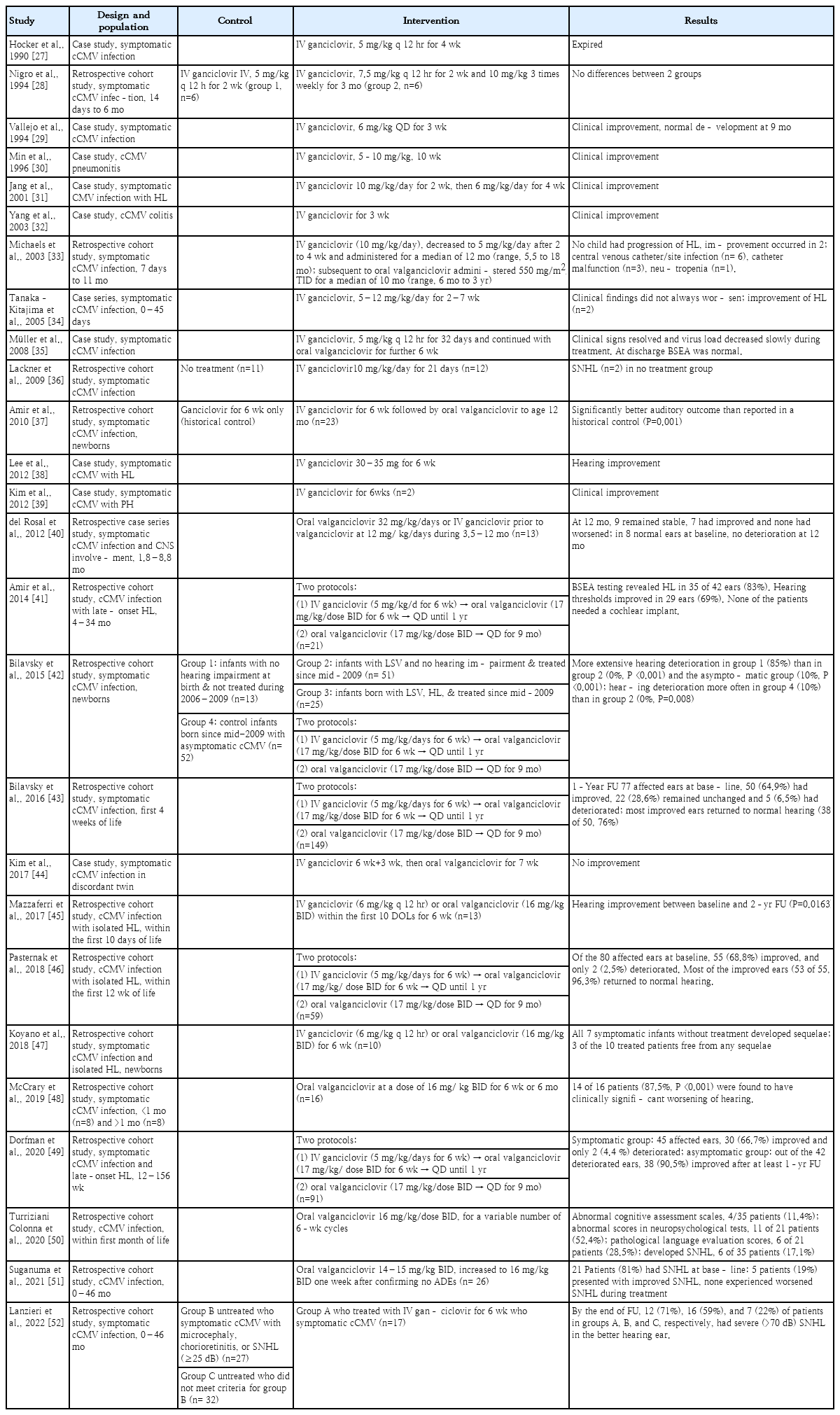

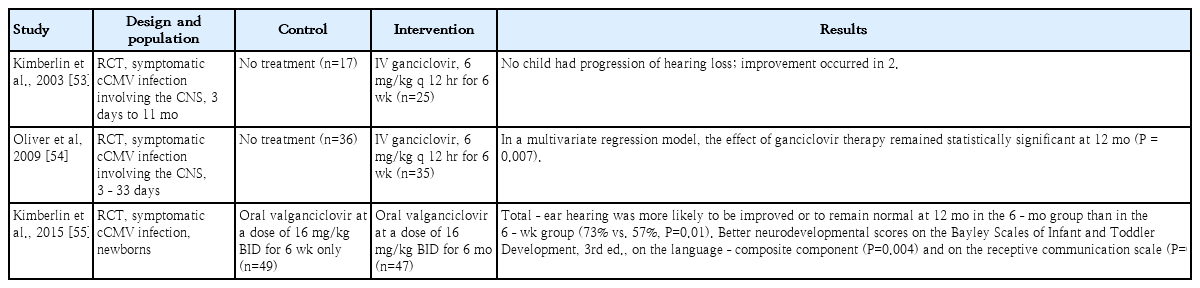

Target population of antiviral treatment

Whether antiviral treatment is required for infants with congenital CMV infection depends on the presence or absence of symptoms. Infants with congenital CMV infection who have significant symptoms, including significant end-organ diseases and CNS diseases, should receive immediate antiviral treatment [2,4,7,9,13]. However, antiviral treatment is not usually recommended in infants with mild symptoms (intrauterine growth retardation, liver enzyme elevation alone, or transient thrombocytopenia) or asymptomatic infants [4,7,9,14]. Tables 1–3 show the characteristics of previous prospective, retrospective, and randomized controlled trials [15-55].

Symptomatic infection

Antiviral treatment is recommended in infants with congenital CMV infection and end-organ symptoms in one or more organs or evidence of CNS involvement [4,14]. Treatment with intravenous ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir in infants with these symptoms improves long-term hearing and neurodevelopmental outcomes [22,33,53-55]. Kimberlin et al. conducted a randomized control study of 6 weeks of intravenous ganciclovir treatment and no treatment in 100 newborns with congenital CMV infection with CNS invasion that showed the ability of ganciclovir to reduce and prevent progressive SNHL [53]. In this study, a total of 43 patients underwent brainstem-evoked response at baseline and 1 year later, which worsened in five of 24 infants administered intravenous ganciclovir 1 year later and in 13 of 19 infants in the control (no treatment) group (P<0.01) [53]. Absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was measured in 89 patients; of them, 29 of 46 ganciclovir-administered patients and nine of 43 controls demonstrated grade 3–4 neutropenia (P<0.01) [53]. Oliver et al. [54] conducted Denver II neurodevelopmental tests at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months and reported much lower rates of developmental delays at 6 and 12 months in the gancicloviradministered versus untreated control group. However, developmental delay was still noted in the ganciclovir-administered group versus the uninfected infants [54].

Asymptomatic infection with isolated hearing loss

Conflict persists regarding whether the benefits of antiviral treatment outweigh the risks in infants with isolated SNHL [4,56]. Completed clinical trials of antiviral treatment are lacking for this particular group. There is currently no clear evidence of the potential benefits of antiviral treatment in infants with SNHL isolates. Kimberlin et al. [55] reported recruiting patients with isolated SNHL, but only one was enrolled; therefore, it is not possible to determine the benefits of treating isolated SNHL in infants. Three multicenter clinical trials are underway in infants with isolated SNHL [57-59].

Asymptomatic infection with normal hearing

In a previous study, antiviral treatment in infants with asymptomatic congenital CMV infection showed no significant effects on hearing improvement [36,60]. Lackner et al. [36] conducted a small randomized study of 23 infants with asymptomatic congenital CMV infection with or without 3 weeks of ganciclovir treatment; among the final 18 infants, none of the 9 in the treatment group had delayed hearing loss versus 2 of nine in the untreated control group. Although the results of this study showed a positive effect in infants with asymptomatic congenital CMV infection, it is difficult to draw final conclusions from this study alone because of the small number of subjects. A phase 2 open clinical trial is currently underway to evaluate the therapeutic effect of oral valganciclovir in infants with asymptomatic congenital CMV infection [61].

Optimal timing and duration of antiviral treatment

In symptomatic infants, antiviral treatment should be initiated as soon as testing confirms a positive congenital CMV infection [62]. In previous clinical trials examining the effectiveness of antiviral therapy for congenital CMV infection, benefits were observed when treatment was initiated within the first 30 days of life [53,55]. Studies examining the benefits of starting treatment after 1 month of age showed some positive results [40,49]. A phase 2 randomized controlled study of the use of oral valganciclovir in infants and toddlers with congenital CMV infection and hearing loss between 1 month and 4 years of age is ongoing (NCT01649869) [59,63].

The current standard treatment period for infants with congenital CMV infection and symptoms is 6 months based on oral valganciclovir. A randomized controlled study by Kimberlin et al. [55] showed better hearing and neurodevelopmental prognosis in the oral valganciclovir 6-month use group; thereafter, oral valganciclovir 6-month treatment became the standard. However, infants with persistent viremia, retinitis, liver disease, and primary immune disorders may require oral valganciclovir therapy beyond 6 months of age. Infants with severe symptoms are monitored for CMV DNAemia, and antiviral treatment is administered if the viremia does not resolve after 6 months [62]. In a series of 23 infants treated with oral valganciclovir for 12 months, Amir et al. [37] found that long-term treatment was safe and associated with improved auditory outcomes compared with previous controls who received 6 weeks of treatment. In a retrospective study by Bilavsky et al. [43] of symptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection who started antiviral therapy during the first 4 weeks of life, receiving this treatment for 12 months with oral valganciclovir significantly improved hearing status. Therefore, further studies are needed to determine the optimal treatment period based on patient condition.

Initial evaluation before antiviral treatment

A comprehensive evaluation of infected newborns is required before antiviral treatment is initiated [4,9,14,62]. A thorough physical examination is necessary to detect the symptoms and signs of congenital CMV infection. Baseline levels were confirmed using tests such as ANC and platelet count. A renal function test that checks the baseline levels of blood urea nitrogen and blood creatinine is used to determine whether a dose adjustment of the antiviral drug is necessary. Hepatic transaminase, total bilirubin, and direct bilirubin levels confirmed the baseline liver function test results. Neuroimaging using brain ultrasound, computed tomography of the brain, or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is required to evaluate the extent of CNS involvement. A hearing test and ophthalmic examination are also required for the baseline setup. A CMV DNAemia test using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is required to confirm the degree of viremia (Fig. 1).

Schematic diagram of treatment and monitoring of infants diagnosed with congenital CMV infection. CMV, cytomegalovirus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SNHL, sensory neural hearing loss; FU, follow-up; VGCV, valganciclovir; BID, twice a day; IV, intravenous; GCV; ganciclovir; CBC, complete blood count; ANC, absolute neutrophil count; LFT, liver function test; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TB, total bilirubin; DB, direct bilirubin; RFT, renal function test; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine.

Antiviral agents

Intravenous ganciclovir or its oral prodrug valganciclovir is currently used to treat congenital CMV infection. Antiviral drugs inhibit CMV replication by interfering with viral DNA synthesis. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that oral valganciclovir has similar efficacy to intravenous ganciclovir [19]. The use of intravenous ganciclovir is only recommended in cases in which enteral supply is difficult; once enteral intake is established, treatment should be changed to oral valganciclovir, which features fewer side effects [7]. Foscarnet and cidofovir are used in cases of refractory CMV infection, ganciclovir resistance, ganciclovir toxicity, and coinfection with adenovirus [64-66].

1. Ganciclovir

Whitley et al. [17] conducted a phase 2 clinical trial comparing ganciclovir treatment 12 mg/kg/day and 8 mg/kg/day for 6 weeks in infants with congenital CMV infection; the former group showed better hearing improvement. After this study, ganciclovir 6 mg/kg/dose was administered intravenously twice a day to treat congenital CMV infection [17,37,53,54,67]. Subsequently, improved hearing outcomes and neurodevelopmental sequelae were reported with intravenous ganciclovir treatment between 6 months and 1 year in a phase 3 study of symptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection with neurological involvement [53,54]. Ganciclovir effectively treated congenital CMV infection, but it was not widely used because it required long-term intravenous infusions with serious adverse effects. Accordingly, Kimberlin et al. [19] evaluated the pharmacokinetics of valganciclovir, an oral ganciclovir formulation, and found that administration of 16 mg/kg/dose twice a day reached the same blood concentration as intravenous ganciclovir. In addition, the use of oral valganciclovir reduced the risk of neutrophil reduction compared to the use of intravenous ganciclovir, and the gonadotoxicity and carcinogenicity induced by ganciclovir were not observed with oral valganciclovir. Thereafter, oral valganciclovir became the treatment of choice for congenital CMV infections. Subsequently, Kimberlin et al. [55] conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing oral valganciclovir for 6 months and 6 weeks in 96 infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infections regardless of CNS involvement; the 6-month group showed better hearing improvement (or even normal hearing) at 24 months compared to the 6-week group (67% vs. 64%, P=0.045) as well as higher language (P=0.004) and receptive communication scores (P=0.003) at 24 months. Many other studies provided evidence that ganciclovir treatment may improve hearing and neurologic outcomes in infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infection [15,16,18,21,22,24,27-47,49,52]. Ganciclovir should be administered via a central venous catheter when possible. If short ganciclovir treatment (<2 weeks) is anticipated, a well-functioning peripheral intravenous catheter can be used for dosing if the intravenous site is carefully monitored during the infusion [3,62].

2. Valganciclovir

In 3 case studies, oral valganciclovir improved or preserved the hearing of infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infection [20,23,40]. The Collaborative Antiviral Study Group conducted a phase 1/2 pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study of oral valganciclovir in neonates with congenital CMV infection with or without CNS involvement in 2002–2007 showed that oral administration at a dose of 16 mg/kg/dose twice daily produced ganciclovir blood levels similar to those with intravenous administration at a dose of 6 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours [19]. In a subsequent randomized control trial by Kimberlin et al., valgancilcovir was administered orally at a dose of 16 mg/kg twice daily; this dosage is currently recommended [2,55,62].

Infants receiving intravenous ganciclovir should also be switched to oral valganciclovir within 2–6 weeks if they are clinically stable and can take oral medications. After switching to oral valganciclovir, treatment should be continued for 6 months.

3. Others

Foscarnet and cidofovir are not routinely used to treat congenital CMV infections, and data on their use in these settings are limited [64-66]. These agents may be used in some cases in which ganciclovir resistance is suspected or confirmed or when severe toxicity occurs during treatment with intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir.

Supportive management

In some cases of congenital CMV infection, symptoms such as sepsis-like illness, myocarditis, viral-induced hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, or severe neurological involvement may be present. In infants with these symptoms, supportive management is important in addition to antiviral treatment. Supportive management includes fluid therapy, blood transfusions, blood pressure control, seizure control, respiratory support, adequate nutrition, and antibiotic treatment of secondary bacterial infections [3,6,62,68].

Adverse effects of antiviral treatment

1. Neutropenia

Neutropenia is known to occur in 25%–60% of neonates treated with intravenous ganciclovir and about 20% of infants treated with oral valganciclovir [53-55,69,70]. Severe cases are rare and usually resolve by stopping antiviral drugs for 1–7 days and re-administering the same dose once the ANC has recovered. Treatment may require discontinuation if the neutropenia recurs [62].

2. Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000 cells/µL) reportedly occurs in 6% of infants during intravenous ganciclovir therapy [69,71]. However, infants with congenital CMV infection often have low platelet counts at birth; thus, the relative contribution of ganciclovir to the thrombocytopenia is unclear. In a randomized controlled trial, thrombocytopenia occurred at similar rates in infants treated with intravenous ganciclovir and in untreated infants (7% vs. 5%, respectively) [53].

3. Renal toxicity

Elevated serum creatinine levels reportedly occur in less than 1% of infants treated with intravenous ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir [69,71]. Doses of intravenous ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir should be adjusted in infants with renal failure [62].

4. Hepatotoxicity

Hepatotoxicity was observed in infants receiving intravenous ganciclovir, especially at a dose of 6 mg/kg or higher [69,71]. A slight elevation of aminotransferase (<100 IU/L) is particularly common in infants receiving oral valganciclovir, which is generally not a problem [62].

5. Problems associated with intravenous catheters

Problems with intravenous catheters are common during ganciclovir treatment. The extravasation of intravenous ganciclovir may cause local reactions, ulcers, and scars. Therefore, intravenous ganciclovir should be administered through a central venous catheter; if oral administration is possible, the switch to oral valganciclovir should be quickly made [33,53,62].

Long-term effects

Animal studies have shown that intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir may involve reversible testicular damage, reduced sperm viability, and carcinogenic effects [64,71-73], but this has not been shown in human studies.

Monitoring

In cases of intravenous ganciclovir or oral valganciclovir for the treatment of congenital CMV infections, periodic blood tests are required to check for toxicity. Checks for ANC and platelet counts are required to confirm neutropenia or thrombocytopenia. Liver function tests (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total and direct bilirubin levels) and renal function tests (blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels) should be additionally performed [14]. ANC and platelet counts should be determined weekly for 6 weeks, then at 8 weeks, and then monthly during the treatment period [19,55]. Monthly liver and kidney function tests are also recommended [19,55]. Quantitative CMV DNA PCR measurements of whole blood or plasma to determine the degree of viral load can be performed to determine the effectiveness of antiviral treatment [3,62,74]. Some studies have shown a correlation between a low viral load and improved hearing outcomes [55,74]. Infants treated for congenital CMV infection should undergo regular hearing examinations up to 6 years of age and followed up with ophthalmic examinations until 5 years of age [7].

Problems requiring solving

A number of problems in the treatment of congenital CMV infections require solving [3,7,9]. In infants with congenital CMV infection, it is necessary to determine whether there is any benefit in starting treatment after 30 days of age. It is necessary to determine whether there is any benefit to treating mild or asymptomatic children, and a comparative study examined 6- and 12-month treatment with oral valganciclovir [35]. As with most drug therapies, studies of the safety and efficacy of antiviral drugs used for treating congenital CMV infection in preterm infants are limited. All clinical trials establishing the pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of intravenous ganciclovir versus oral valganciclovir were limited to infants born at ≥32 weeks’ gestation at a birth weight of ≥1,200 g. Although there are several case studies on the effective use of intravenous ganciclovir and oral valganciclovir in preterm infants aged <32 weeks’ gestation, clinical studies on antiviral treatment are lacking [13,35,75-79]. Further clinical studies are needed to establish a treatment for congenital CMV infection in preterm infants.

Ongoing trials

Various institutions are currently conducting studies on treating congenital CMV infections. The Collaborative Antiviral Study Group is conducting a phase 2 randomized controlled trial of oral valganciclovir therapy in children up to 4 years of age with congenital CMV infection and SNHL isolates (NCT 01649869) [58]. A nonrandomized single-blind clinical trial is investigating whether early treatment with oral valganciclovir up to 12 weeks of age in congenital CMV infection with SNHL may prevent the progression of hearing loss (NCT02005822) [59]. In addition, a clinical trial of whether oral valganciclovir for 6 months can prevent hearing loss in children with isolated SNHL has been completed, and the results are currently being analyzed (NCT03107871). Another clinical trial of whether oral valganciclovir treatment for 6 months can prevent hearing loss in children with isolated SNHL has also been completed and is under analysis (NCT03107871) [57]. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases is conducting a phase 2 clinical trial of oral valganciclovir administration in asymptomatic infants (NCT03301415) [61].

Conclusions

Congenital CMV infection is a major cause of nonhereditary SNHL that can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders in the brain. Infants with symptomatic congenital CMV infection may benefit from hearing and neurodevelopmental prognoses, especially if antiviral therapy is initiated within the first month of life. The currently recommended drug regimen for symptomatic infants with congenital CMV infection is as follows: infants with life-threatening symptoms are initially treated with intravenous ganciclovir for 2–6 weeks and then switched to oral valganciclovir, while those without life-threatening symptoms are treated with oral valganciclovir for the entire 6-month period. Monitoring of ANC, platelet count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and liver function tests is required to identify neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, renal failure, and liver failure during antiviral treatment. However, additional studies are needed of the treatment of preterm infants born at <32 weeks’ gestation, starting in those older than 1 month of age, of those with isolated SNHL, and of asymptomatic infants.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.