COVID-19 among infants: key clinical features and remaining controversies

Article information

Abstract

Infants aged <1 year represent a seemingly more susceptible pediatric subset for infections. Despite this, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection has not been proven as more serious in this age group (outside the very early neonatal period) than in others. Indeed, a considerable number of asymptomatic infections have been recorded, and the symptoms and morbidity associated with COVID- 19 differ minimally from those of other respiratory viral infections. Whether due to an abundance of caution or truly reduced susceptibility, infections in infants have not raised the same profile as those in other age groups. In addition to direct severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 diagnostic tests, laboratory markers that differentiate COVID-19 from other viral infections lack specificity in infants. Gastrointestinal presentations are common, and the neurological complications of infection mirror those of other respiratory viral infections. There have been relatively few reports of infant deaths. Under appropriate precautions, breastfeeding in the context of maternal infections has been associated with tangible but infrequent complications. Vaccination during pregnancy provides protection against infection in infants, at least in the early months of life. Multi-inflammatory syndrome in children and multi-inflammatory syndrome in neonates are commonly cited as variants of COVID-19; however, their clinical definitions remain controversial. Similarly, reliable definitions of long COVID in the infant group are controversial. This narrative review examines the key clinical and laboratory features of COVID-19 in infants and identifies several areas of science awaiting further clarification.

Key message

· Clinical studies of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in infants should be supported by rigorous laboratory diagnostic criteria.

· Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spreads to infants similarly to other viral respiratory infections.

· Among infants ≤1 year of age beyond the immediate postpartum period, COVID-19 is relatively mild, but even the low risk of severe disease requires prevention.

· Comorbidities increase infection vulnerability and complications in infants.

· Clinical and laboratory data do not sufficiently distinguish COVID-19 from other respiratory viral infections.

· Coinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is uncommon among infants.

· Unique infection sequelae, including multi-inflammatory syndrome in children and neonates and long COVID require further study and refinement of diagnostic criteria.

· Infection control standards applied to mother-infant dyads should be tempered by standard preventive strategies, maternal input, accommodation potential, and overall safety.

· Maternal vaccination prevents disease in early infancy.

Introduction

Although coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) affected all age groups very early in the pandemic, several studies have proposed that children, especially infants ≤1 year of age, were much less affected and most often experienced relatively minor illness [1,2]. Some studies published well into the pandemic continued to echo the relatively mild nature of infection among young patients [3]. There is now considerable information forthcoming on the state of COVID-19 among children that has extended to include newborn and infant populations. Early features of maternal and newborn infections have largely been confirmed from earlier analyses [4]. This narrative review examines key aspects of COVID-19 among infants ≤1 year of age outside the immediate postpartum period. In addition to recognizing the important facets of infection in this age group, several controversies and future topics of concern have emerged. These are highlighted in this collation and serve as substrates for further testing.

COVID-19 among infants

1. Risk factors for infection

The risk factors for infection in this age group are not well understood. Most emphasis has been placed on examining the associations of various demographic and clinical factors with hospital admission, illness severity, and mortality. Comorbidities in particular have been analyzed in such studies [5-11]. One confounding issue in this regard is the definition and expressed inclusivity of focused comorbidities given that the enumeration of the latter could conceivably be high. Schober et al. [6] reported that particular comorbidities associated with severe disease, but some individual conditions or the total comorbidities were not. A dilutional effect on the statistical analyses from the overinclusion of variables could be anticipated.

The presence of comorbidities increases a patient’s risk of hospital admission [11]. Those with underlying illnesses before COVID-19 also have more serious infections [6,8-10,12,13]. The comorbidities most associated with adversity are prematurity, cardiac, and, to a lesser extent, neurological and chronic lung entities [6,8,11,12]. There is conflicting information on the role of congenital anomalies alone [6,7,9]. What generally emerges is that, while the severity of COVID-19 generally increases with age, greater severity is noted at the younger end of the spectrum including complicated and premature newborns. The latter is consistent with the susceptibility to other respiratory viral infections at a very young age.

2. Role of contact spread

Despite considerable direct studies of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, the mechanisms of spread largely resemble those already known for decades for other respiratory viruses, including other endemic coronaviruses [14-17]. The issues ofthe degree of respiratory or airborne spread remain contentious, but such discourse is mired in semantics [14]. An infected infant has a known infected close contact in the majority of instances [11]. The contamination of nearby air and solid surfaces is a given; thus, the implementation of respiratory and enteric infection control precautions is essential.

Nosocomial transmission is accepted and includes infants as young as those in the early postpartum period [2,8,11,18-24]. Some groups have experienced a paucity of such transmissions, but institutional outbreaks, including infants, have been cited [2,19]. Furthermore, there may be a very high rate of secondary infections in the outbreak setting affecting newborns, mothers, and healthcare workers [2]. For individual perinatal infections, mothers and healthcare workers can be virus vectors [21]. Despite the subsequent nosocomial transmission, most rationale for institutional care involves reasons other than the proper infection [21]. The latter among very young infants in particular includes prematurity or other noninfectious perinatal events [8].

Exposure to infected mothers is an established risk factor [22,23,25]. This is especially true when the newborn–maternal contact occurs if the mother first becomes infected in the immediate postpartum phase [25]. Newborn in-rooming may be associated with a higher risk of infection, but no association was found in feeding mode in one study [8]. The dissociation of infants from mothers or other direct caregivers must be considered in the overall context of infant, maternal, healthcare worker, and others’ safety. Collective decisions must be tempered by unique circumstances regardless of whether a pre-specified infection control technique is applied. When exceptions arise, consultation with infection control services is a moral obligation and a mandate.

Whether for infected mothers, direct caregivers, family, or other attendees, most infants have a history of close contacts [5,11,13,23,26-34]. The frequency of presumed infected contacts ranges from 36.6% to over 90%. Of the studies that have examined vaginal samples from women with established infection, the finding of a positive test is rare [24,35-37]. Of these studies, only one positive sample was obtained, but live virus was not specifically sought [36]. Regardless, it is firmly established that the live virus can be excreted in stool samples of SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals, and such proximity to the vaginally delivered infant carries a risk [17]. Nucleic acid testing of blood from some infections may identify the presence of the virus. Such positivity might be detected in maternal blood or cord blood and is cited as having the potential to detect the virus in placental samples [4,38]. Many such studies have not sought cultivable viruses; however, at least for the placenta, viral presence has been documented on the fetal and maternal sides through in situ histochemistry techniques.

3. Asymptomatic versus symptomatic disease

Outside the concept that COVID-19 might be a relatively mild illness among infants, a considerable proportion of patients test positive and are deemed asymptomatic for the observed duration [39,40]. The phenomenon of asymptomatic infection has been found for all pediatric ages [1,41]. The frequency of such a state in a given infant population must certainly depend on the cause of the initial testing. Where testing is performed, the bias to include asymptomatic patients in screening efforts will evidently increase the proportion of apparent asymptomatic infections, as will the testing of contacts of infected patients (e.g., outbreak testing scenario) since most will be asymptomatic at the time of the intervention [2,42,43]. Early in the pandemic, asymptomatic infections were identified in 16%–25% of cases [28,44]. Subsequently, for different age clusters within the infant age group from cumulative reviews or individual reports, the frequency of asymptomatic but test-positive patients was 0.8%–46.2% [5,8,11,21,24,45-52]. When asymptomatic infections gained attention, it was inevitable that some infants would be admitted to the hospital for observation given the thenuncertainty of the clinical course to follow [24]. The inclusion of mild infections among those numbers with presumed asymptomatic infections increases these frequencies to the vast majority of patients in a given study [2]. The meaning of asymptomatic infection must also be considered in the context of the fallibility of the laboratory diagnosis when positive test results are close to the laboratory analysis threshold so chosen as discussed below.

4. Manifestations of infant infection

Distinguishing COVID-19 from other respiratory infections can be challenging. For example, one study found only the nonspecific symptoms of lethargy and poor feeding as being more common among SARS-CoV-2 infections in infants <2 months of age [53]. Servidio et al. determined that patients <3 months of age with COVID-19 infections were more likely to become febrile than those with non-SARS-CoV-2 infections but the latter were more often admitted for intensive care [3]. In a study of bronchiolitis, patients’ demographic data, clinical variables, and length of hospital stay were similar for SARS-CoV-2 and other viral causes except for a higher incidence of fever with COVID-19 [27]. Evidently, there is little clinical evidence to differentiate COVID-19 from other viral respiratory illnesses for all severities, and where any such differences may exist, the predictive values would be low. The frequency of infected newborns seen in prospective cohorts has been very low [22,25,54-57]. Among these studies, the number of those overtly symptomatic is another lower proportionate fraction. Although this infrequency is rather consistent, some studies have not carefully considered the impact of the close timing of maternal infection on the delivery process.

Clinical manifestations of infected infants have been collated in many studies from a considerable diversity of geographic regions and with now considerable cumulative numbers [3,5,9-11,13,21-24,26,30-32,34,41,45,46,48,51-53,58-62]. Table 1 details the more common disease features cited to date. Small case series, case reports, and reviews have mostly been consistent [28,29,62-66]. Definitions of symptom categories are inconsistent among these studies, and not all categories of disease manifestations are necessarily considered. These studies tally their findings variably in retrospective and prospective manners. With some exceptions, the pattern of clinical manifestations is relatively consistent across geographically variable populations and ethnic groups. Although fever is relatively common, a consistent association between it and other clinical manifestations is less apparent. Nevertheless, it is surprising that respiratory manifestations are much less appreciated. Although less common, gastrointestinal symptoms can be prominent and may be the chief complaint. Skin manifestations are also common. Neurological events are variably categorized and may be associated with relatively weak signs, such as poor feeding, irritability, and/or inactivity. All of the latter are necessarily complicated by the appreciation of the same patient population for whom clinical assessment is complicated by age.

In addition to the above, studies have published unique presentations such as bronchiolitis, parotitis, croup, bradycardia, arrhythmias, cardiomyopathy, acute kidney injury, necrotizing enterocolitis, late-onset sepsis, and coagulopathy/thrombosis [27,55,61,67-72]. The need for ventilator support is rare [61,73,74]. Many reports are complicated by occasional bacterial coinfection early or late in the COVID-19 disease course, and underlying comorbidities may also present with associated overlapping symptoms and signs. Anecdotes of chronic lung disease after infection have emerged, but the latter must be gauged in the context of whether infants have other comorbidities such as lung prematurity [75].

Early reports of the pandemic highlighted a seemingly unusual presentation of COVID-19 among children, often with a later-timed presentation [76,77]. This clinical entity, however variable, manifested as an acute inflammatory illness with or without fever and mimicked some aspects of Kawasaki disease or toxic shock syndrome. Early reports more commonly cited older children. Fever, rash, conjunctival flare, peripheral edema, gastrointestinal involvement, and extremity pain were common features, and several patients experienced associated vasogenic shock. Respiratory illness, more typical of COVD-19, was present in many patients. Reports of infants with this illness have emerged, and the clinical picture has been labeled “multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children” (MIS-C). Later, there also emerged some concern of a similar potential illness among neonates (i.e., birth to 1 month) to which the term “multisystem inflammatory syndrome in neonates” (MIS- N) was applied. The variations inherent in such illnesses have become more apparent; therefore, several clinical definitions have emerged. Overall, it is suggested that very few SARS-CoV-2-infected children suffer from MIS-C [59,78,79]. Among all pediatric MIS-C in 2 of the latter studies, some 1.7%–2.6% were <1 year of age. MIS-N among infants <1 month of age was estimated to account for only 0.1% of all infections [9]. MIS-C may be a milder illness for those <1 year of age [80]. These entities are discussed further below.

Laboratory studies are not generally and sufficiently discriminative for COVID-19 versus other viral infections, and there are minor and inconsistent laboratory markers to distinguish between milder and severe COVID-19 [9,10,21,24,48,53,60,81-83]. While some patients present with relative generalized leukocytosis, leukopenia, polymorphonuclear leukocytosis, neutropenia, or lymphopenia, it is difficult to use any such trend to confidently distinguish viral causation or respiratory disease severity. Similarly, any trend alone shown for platelet count, liver function tests, and C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, and troponin levels did not lead to tangile indicators with reasonable predictive values. Minor improvements in prediction may be achieved using combinations of laboratory markers other than specific SARS-CoV-2 testing. Most trends for the association with COVID-19 are, at best, similar to those seen with other viral infections in infancy with some minor exceptions.

Reports on neurological diseases during the course of COVID-19 vary considerably, and it is unclear whether such complications arise due to direct viral infection or any underlying complications. All pediatric age groups are potentially affected [84]. Although most patients have symptoms and/or signs of respiratory infection, some lack such apparent manifestations. Weak neurological signs include lethargy, fussiness or irritability, poor feeding, inactivity, drowsiness, apnea perception, and mild hypotonia. Although there may be reference to “neurological” complications, the details of the latter are relatively nondescript [58,85-87]. It is also not apparent if the collations and their proportionalities are influenced by selection bias, but the proportion of infants meeting soft or hard criteria for neurological presentations reached 12% in larger reviews [10]. Seizures of variable types are common among the more concrete neurological events [9,24,28,30,49,88-97]. As expected, some are particularly detailed as febrile seizures [24]. In a large American multicenter surveillance study, neonatal COVID-19 was accompanied by a 1.9% frequency of seizures; the frequency did not differ significantly between severe and non-severe patient groups [9]. A relatively similar frequency was found in an Italian multicenter study [24]. The latter, however, contrasts with another large review in which the outcome of the neurological presentation was more common among infants with severe COVID-19 [10]. Other infants reportedly had encephalopathy or meningitis or meningoencephalit is [9,49,88,92,93]. Intraventricular hemorrhage has arisen during the course of infection [9]. Cerebral venous thrombosis has also been described[98].

Neurological complications accompanying MIS-N and MIS-C have also been reported [49,58,80,85,86,91,92,94]. As stated above, these complications include seizures. One review cited an incidence of central nervous system involvement as high as 50% in these patients [85]. Two infants aged 4 and 9 months presented with bulging fontanelles [99,100]. One of the latter had evidence from imaging suggestive of increased intracranial pressure [100]. The illnesses of both patients resolved without other neurological sequelae.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examinations in the context of COVID-19 are usually part of a sepsis workup for infants. There are relatively few reports on CSF analyses. Of the studies reporting on the cell counts of CSF, 25 were reportedly acellular [30,34,58,89,90,92,93,95-101]. Two reports citing pleocytosis in the CSF documented a monocytic or mixed count [34,102]. One of the latter was assessed directly for SAR-CoV-2 by amplification technology and deemed negative [34]. Of the 5 CSF direct viral assays, 4 were negative and 1 was positive but in the context of an acellular count [34,89,90,93,97]. None of these CSF analyses were assessed for live viruses.

Imaging during the course of or follow-up for patients with neurological manifestations is variable [87]. Pathology from magnetic resonance imaging identified cystic cavitation or acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalitis [87,90,96,97,102]. Computed tomography may be suggestive of encephalitis or ischemic lesions [93.95].

Long-term assessments after neurological events are scarce [45,103,104]. One study of the neurodevelopmental score status at 6 months reported that those born during the pandemic had lower scores, whereas the variable of maternal infection at any time during pregnancy had no such association [104]. The same authors did not find that maternal infection was associated with adverse long-term neurological outcomes [103].

Infants born to mothers who had prenatal COVID-19 presenting for care can receive a lower rate of acuity or concern than those born to mothers with no history of infection [105]. The latter most likely represents greater diligence assessing infants in the context of infection with the assumption that they might be more at risk for complications. When infected infants are <1 month of age, there is a higher rate of intensive care admission, and there is generally a greater tendency to admit very young infected infants [106,107]. The mean hospital stay is relatively short [26].

5. Potential for infant mortality

Mortality in infants with COVID-19 has been frequently reported. From reports with small numbers of infected patients <1 year of age, the frequency of death seems alarmingly high at first glance [7,12,32,46,49,55,58,108]. However, it is unclear whether such frequencies reflect patient access to medical care. It is difficult to ascertain reporting biases in other respects. These findings also contradict the negligible mortality that was determined in a very early review of infections through April 2020, at which point the mortality rate was only 0.006% [44]. Other studies reported no deaths among reasonably sized patient pools [27,34,106]. Consistent with the latter, other studies that stratified patients by age into <30 days, <6 months, and <1 year groups reported mortality rates of approximately 0.1%–0.5%, 0.4%–0.7%, and 0.5%–2.2%, respectively [9,10,11,13,23,48,51,52,61,80,109]. These studies should also be individually viewed given the heterogeneity of whether the mortality rates were ascribed to all patients with infections versus only those admitted to the hospital. Overall, considerable data suggest that infant deaths from COVID-19 are relatively infrequent. Where any such death does arise, it is inconsistent whether the event could be directly related to viral infection or other preceding or postinfection complicating factor(s).

Other unique findings have been reported by other studies. Cozzi et al. [27] found no deaths among 18 patients whose diagnosis was initially COVID-19-associated bronchiolitis. COVID-19 has been associated with an increase in all-cause mortality, but the association is minimized when the data were controlled for lethal newborn malformations [7]. For an American study of infected children <6 months of age and admitted to the hospital, the mortality rate was not significantly different during the delta (0%) versus omicron (0.75%) periods [51]. The frequency of all-cause mortality may be higher when maternal infection occurs much closer to delivery [110]. Another study found no difference in mortality between nonsevere (0%) versus severe (0.96%) disease among infants admitted to the hospital.10) Comorbidities may be associated with mortality, but it must also be considered that, in the face of congenital anomalies and other significant comorbidities, the cause of death may not always be truly ascribed to SARS-CoV-2 [23,32,111]. Deaths among children with MIS-C or MIS-N presentations have been published [9,46,49,112,113].

Autopsy studies of deceased infants are meager, and most accumulation of COVID-19-related autopsy information stems from the findings among deceased adults [114,115]. Reviews for pediatric autopsy tend to focus on older children, and the proportionate number of infants aged <1 year has been <50% [116-118]. A single case report in the context of an infant with infection with the omicron variant detailed only pulmonary findings [119]. A report of neuropathology in 4 infants is also available [120]. In contrast, there are considerable studies on placental and stillbirth pathology. Most other autopsy reports on infants focused on pulmonary findings [112,121-123].

Given that the infant mortality rate is considerably low, it is important to question the affinity of the virus for the relatively immature respiratory tract of infants in the context of innate immunity and its variations with age. There is an age-related variation in respiratory ACE2 virus receptor expression, but there are conflicting views on how such variations in the context of other infection-modulating factors may truly influence age susceptibility, especially for pediatric and infant cohorts [124,125]. There are several examples of other respiratory infections in which infants are much less likely to suffer infections than older children (e.g., Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis and Mycoplasma pneumoniae lower respiratory infections).

Controversy regarding infants

1. Diagnostics limitations

Generally speaking, it is common for the academic readership to accept scientifically published data with the assumption that diagnoses of SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19 are veritable. However, diagnostic methods have matured since the onset of the pandemic. Surprisingly, even by 2023, many such publications have not established more definitive diagnostic criteria. The latter causes jeopardy, especially when reviews are attempted in the form of meta-analyses.

The majority of the diagnostic studies cited depend on viral genome amplification and detection. Although these are generally considered to be state-of-the-art methods that have undergone many improvements, they have several inherent limitations. For any laboratory diagnostic method, it is assumed that the specimen quality is sufficient for testing. Not only is there the potential to obtain a poor sample that is not truly representative of the infected site, but the contamination of newborn surfaces by maternal contact remains possible.

The threshold for determining a positive result in an automated genetic amplification test is relatively arbitrary, and while there is a good correlation between quantitative determinations and live virus presence, ambiguity may arise when the determined values are close to the strict threshold [126]. The quality of such testing has matured. Early during the pandemic, some centers established genetic amplification diagnoses based on a single subgenomic target. Since multiple targets were used thereafter to improve the specificity of a positive test,the reliability of the research matured (improved); however, aboratories could vary the targets used, causing interlaboratory variability in diagnosis. The subgenomic presence of a virus does not necessarily indicate the existence of a live virus; rather, it can continue past the absence of a live virus for a considerable number of days, when the patient is no longer infectious. The direct culture determination of live viruses can also vary among laboratories and has largely been avoided because of the high level of laboratory containment that is deemed imperative [127]. Both serological diagnostics and antigen detection have interpretive limitations, especially when used in isolation.

Overall, in understanding case reports, single-institutional small or large series, or multicenter studies, it is essential to estimate the veracity of diagnostic methods.

2. Age-related susceptibility

Well-designed studies that examine the age-related susceptibility of infants, either for infection alone or for determining disease intensity, are lacking. Early in the pandemic, it was suggested that infants were more vulnerable than older children, but published data were relatively sparse [1,44,48]. Most further analyses are usually retrospective and often do not control for critical variables that would enable the proper determination of age-related susceptibility.

Regardless of the limitations of existing analyses, several themes have emerged. Among children with COVID-19, some 20%–35% are <1 year of age [10,12,78,111,128,129]. The rate of hospital admission may be higher for younger infected patients [11,128,130]. Admission, however, may also occur commonly for reasons other than the infection proper [12]. The rate of medically attended COVID-19 may be higher among younger patients [33]. Prematurity may be a risk factor for hospital admission [12]. A European multicenter study found that the risk for intensive care increased with young age [107]. Another study suggested that the latter risk was more so for those <1 month of age [78]. Whereas younger age may be at higher risk of hospital admission, those infants may not necessarily require more hospital interventions [128].

In contrast, in Scottish registries, there was no evidence of increased infection at a younger age; indeed, infants <1 month of age had among the lowest infection frequencies [106,130]. Some researchers found that age was not an independent risk factor for medical attention, hospital admission, or intensive care requirement after infection [6,41,111]. For infants <1 month or <1 year, more illnesses were non-severe than severe [10,41]. In a study from Italy, the frequency of presenting illnesses per week did not significantly differ among infants <1 month old [24].

Regarding the above differences, it is inevitable that younger age will attract bias in terms of vulnerability. Infants may be more likely to attract greater attention or require hospital admission even when relatively asymptomatic. Such concerns would likely have been more common in the early phases of the pandemic, when more questions about COVID-19 remained unanswered. The benefits of determining whether there is truly age-related susceptibility to infection and/or disease may be valuable for understanding the pathogenesis.

3. Coinfections

Infections that coexist with COVID-19 may be acquired fortuitously or arise in the context of complicating existing SARS-CoV-2 infections. For the latter, early coinfections comprise typical bacterial respiratory flora as secondary invaders or late opportunistic infections arising as a consequence of prolonged COVID-19 or secondary infections due to physiological or immune compromise.

For concomitant infections with other viruses, understanding the mechanisms of current laboratory diagnostics is critical. In searching for the breadth of viruses that may potentially infect the respiratory tract, multiplex genome amplification assays are commonly applied; indicators for a positive diagnosis are set at a given threshold of automation indicators but are not guaranteed for live virus presence. Effectively, the codetection of 2 or more viruses in a clinical sample does not guarantee the actual simultaneous presence of 2 live infecting viruses [131]. Moreover, some positive signals for detection, at an arbitrarily defined threshold limit of positivity, may not truly be indicative of viral presence, especially when secondary corroborative testing is not routinely applied. This dilemma was evident when considering codetection in the face of other coronavirus epidemiologies and where it was suspected that high frequencies of coinfection were implied [132]. Therefore, codetection does not necessarily imply coinfection. This does not diminish the potential, however, for codetection to imply that, although not simultaneously infected, the first hit-second hit of consequent infections may suggest one active infection shortly following another. The circumstances for secondary bacterial or fungal infections usually differ because these categories of infections are determined using culture methods. The latter is more common, with prolonged hospital stays and complicated COVID-19 features.

It has been generally accepted that quarantine measures during the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the frequencies of other common respiratory infections among infants. With the lifting of preventive measures, a rebound has occurred in other common viral infections alongside COVID-19. Two studies found viral codetection rates of 10%–53% of diagnostic samples among infants presenting to hospitals [12,24]. Doná et al. [24] reported that such codetection was not associated with severe disease. In any such codetection, the rhinovirus/enterovirus category seems overrepresented. Other studies, however, reported a much lower frequency of codetection, including 0% at times [27,53]. A small patient series of infants admitted to the hospital reported that two of 18 patients had a secondary late bacterial infection [26]. For infants seen in emergency departments, secondary bacterial infections were not detected in any patient at the same time or bacterial infections were not seemingly secondary as COVID-19-related complications [53,81,133]. A similar study reported no significant difference in frequency of secondary infections when infants presented with versus without COVID-19 [60]. Of note, another study of the entire pediatric age group with COVID-19 proposed that co-detections were associated with a greater probability of the need for hospital intensive care [107].

4. Breastfeeding

The contamination of an infant through direct skin-skin contact during the course of breastfeeding will inevitably occur, as it may spread through respiratory droplets given the infant-mother proximity. However, does the latter result in considerable secondary spread from an infected mother and overall considerable medical peril?For example, a study from Peru found that vaginal delivery, breastfeeding, and patient isolation did not affect patient complications during the hospital stay [50]. Breast milk samples may test positive for virus detection with genetic amplification technologies but no live virus [134]. If breast milk is not the direct source of live virus, post-milk excretion contamination, other infant contact, or respiratory spread remain potential modes of transmission. Rooming-in with an infected mother increases a neonate’s risk of secondary infection [8].

The practical experience is that mothers are quite likely to initiate breastfeeding during a postpartum hospital stay and continue thereafter, but they have been less likely to breastfeed if infected within 2 weeks before delivery [20,135,136]. For those infants infected within the first 3 months, many will have been breastfed [25,30,43]. However, the frequency of such breastfeeding does not carry a considerable risk [20,43]. Of further interest, when infected mothers are separated from newborns until postpartum discharge, the feeding of unpasteurized milk was not associated with proximal infant infections [137]. When infected mothers and their infants room together, the use of infection control precautions including masking, appropriate hand hygiene, and contact vigilance are associated with negligible secondary infections [20,136]. In practical terms, maternal-infant dyads are not uncommonly separated at birth [25]. The frequency of such separation was much higher earlier in the pandemic, presumably out of an abundance of caution. Very few infants were cared for in the absence of infection control precautions [25]. Notably, the diagnostic test results of the newborns did not appear to influence dyad separation, isolation precautions, or infant feeding patterns.

The benefits of breastfeeding for nutrition, psychosocial outcomes, and immunity are not disputed [138]. The timing of maternal infection relative to birth is important because live virus excretion during infection may persist for 5–14 days [139-141]. The benefits of breastfeeding, when necessarily interrupted for several days, do not excessively compromise its long-term benefits. Breast milk may be pasteurized successfully to minimize contamination [4]. Infant-maternal interactions can be guided by proper infection control techniques and personal choices made available. The management of infant-maternal interactions must also be considered in terms of the care setting, healthcare workers, secondary nosocomial infections, and newborn fragility.

5. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children and neonates

Furthermore, some ambiguity emerged in the analysis of MIS-C and MIS-N. Its inflammatory and multisystem nature suggests a distinction from the more common respiratory-dominant illness. Although suggestive of an altered pathogenesis, a clear pattern and series of complications led to the creation of several formats for diagnostic criteria (Table 2). The uniting all of such diagnostic criteria involved the inclusion of age specification, with or without hospital admission, fever, the involvement of 2 or more body systems, laboratory evidence of inflammation, the exclusion of other microbial causes, and proof of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Similar criteria were used for MIS-N, including age <1 month and evidence of maternal infection. Although SARS-CoV-2 infection documentation of some form unites these clinical groups, the nonspecificity of many of these criteria detracts from the establishment of a coherent and unified clinical entity. Otherwise, there did not appear to be a secondary diagnostic marker with high specificity. This is akin to the use of clinical diagnostic criteria and associated perils for several other syndromic illnesses [146]. Such heterogeneity is especially illustrated by variations in case reporting [91,94,101,147-150].

Where details have been provided, it is possible to exemplify several potential problems. For patients who were previously administered antibiotics, a noninfectious cause of the patients’ manifestations is possible as an adverse reaction, such as rash, pyrexia, ocular manifestations, diarrhea, and vasomotor instability. The latter is more likely to be mitigated or altered by the coadministration of systemic corticosteroids, which have been used to treat COVID-19. When alternative infectious diagnoses are sought by multiplex respiratory laboratory panels, some relevant pathogens, such as parvoviruses, may be forgotten. However, other noninfectious diseases may be causative in whole or in part.

For the clinical manifestations that are recommended as diagnostic criteria, variations may cause considerable interstudy differences. Gastroenteritis is a common feature of pediatric COVID-19, including some patients with a predominance ofthe same [17]. Among reported MIS-Ccases, mild gastrointestinal symptoms occurred in up to 20% [5)]. Therefore, if the respiratory system is included as a clinical diagnostic criterion, the respiratory and gastrointestinal body systems would allow the inclusion of many more patients. For laboratory markers of inflammation, the potential choices are considerable; thus, the potential is high for a patient to have any one above the diagnostic threshold at some time during their illness. However, the latter markers alone yielded relatively low predictive values. When defining MIS-N, the sole dependence on a marker of maternal infection preceding birth involves jeopardy, especially when such a diagnosis is dependent solely on serological criteria and may be timed variably before birth [58,151]. A proposal that MIS-C and MIS-N are SARS-CoV-2 antibody-dependent draws interest but remains unproven [72,93]. Other studies of pathogenesis have emerged [85,86,152-154]. The similarities to Kawasaki disease and toxic shock syndrome continue to be explored, and rightfully so [155]. Some data suggest the possible difference in MIS-C incidence depending on the SARS-CoV-2 strain dominance [79].

6. Protective role of maternal vaccination

The role of maternal antibodies in newborn and infant protection against various infections, including those predominantly of a respiratory nature, is most often undisputed. Whether transplacental as more quantitatively derived by the end of pregnancy or via breast milk thereafter, maternal antibodies can be delivered systemically or mucosally to impart protection, which is usually time-limited and progressively diminishes from birth or after the cessation of breastfeeding. Such concepts of protection have been reasonably well-established for many coronaviruses, especially in the veterinary field [156]. In parallel to the latter, breast milk anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody declines in the first year [157]. In keeping with past experience from other respiratory virus infections, there is a strong correlation between increased circulating maternal antibody levels, increased quantities of circulating infant antibody levels, and increased breast milk antibody levels [157]. The move to protect mothers from serious disease and protect their infants via the latter through vaccination was justified on theoretical grounds early but then corroborated specifically for COVID-19. It was later shown that vaccination during pregnancy did not overtly affect common delivery or neonatal outcomes [158,159].

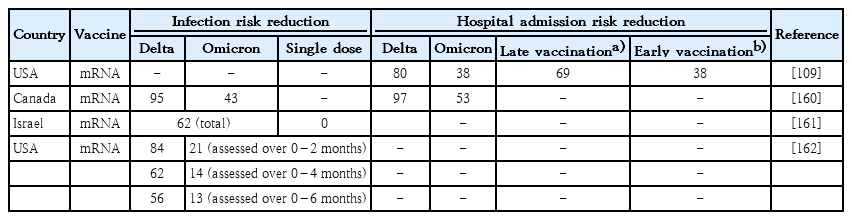

Given the novelty of SARS-CoV-2 infections, large population studies to date of the impact of maternal vaccination on newborns and infants are relatively experimental, but success as measured in the prevention of infection or mitigation of disease severity has become evident (Table 3) [109,158-162]. The latter studies included retrospective analyses of sizable populations and focused on mRNA vaccination protocols.Two maternal vaccinations generally provided protection against infection and hospital admission among infants throughout the first 6 months of life. Such protection was greater for the delta variant, which is closer to the ancestral strain used for vaccine derivation, than for the omicron variant, which captures an evidently distinct serological profile [163]. Vaccinations given closer to the time of delivery (but >2 weeks before delivery) were associated with better infant protection. Whether for delta or omicron immunophenotypes, protection waned over 6 months. Single maternal vaccination provides minimal protection. Children of vaccinated mothers had less severe COVID-19 when admitted to the hospital for care. Three vaccine doses improved protection against the omicron immunophenotype. One study group’s finding that all-cause infant (<6 months) mortality was reduced when mothers suffered COVID-19 in pregnancy more than 2 weeks prior to birth is also consistent with the aforementioned findings [110].

Prevention of infant infection and hospital admission by maternal (2-dose) coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination regimen

Many concerns should be addressed in future studies of maternal vaccination and infant protection. Would infants <6 months of age benefit from direct vaccination when their mothers were appropriately vaccinated during pregnancy? How do non-mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations compare to mRNA vaccines? Is infant vaccination warranted when mothers contract COVID-19 during pregnancy? Do maternal vaccination and/or infection provide protection to infants during subsequent pregnancies? Although of great relevance, such concerns regarding the key questions to be raised in this context are not overly exhaustive. Such concern may also be viewed in the context of how the presence and quality of antibody may have varying roles for mother or infant [164]. In addition, a more precise definition of what constitutes “protection” is generally lacking, although studied by several authors [165]. There is also ambiguity in the definition of protection for infection versus serious or otherwise advanced illness.

7. Long COVID

Whether expressed as long COVID or other late manifestations, the longitudinal impact of maternal COVID-19 on infants remains concerning [166]. Also, whether fulfilling a well-designed definition of long COVID or not, some potential long-term consequences of maternal-neonatal infection continue to surface [167]. Like the designations of MIS-C and MIS-N, precise definitions of long COVID are controversial, and many variations on this theme prevail. It must be emphasized that the severity of a viral illness largely determines the nature of the convalescence required and, to some degree, the pattern of complications. These conditions are often referred to as postviral syndrome or postviral fatigue [168]. Most patients resolve postviral illness sequelae over variable courses with supportive treatment alone. In this context, the nature of infants and the need for caregiver observation to dominate the main clinical complaints probably reduce the frequency of perceived long-term COVID-19-related issues.

Common case definitions for long COVID, if taken literally, would encompass a very broad and overwhelming working basis for patient inclusion. From copious past examples, such overarching clinical and predominantly syndromic definitions often add to the confusion [146]. Outside of attributing subsequent diseases to a former laboratory diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection, there are few other more tangible credible diagnostic confirmations. It is likely that overinclusion or overgeneralization has the potential to muddle the study of those who may have a bona fide long-term virus-specific illness. With the vast number of confirmable diseases in the community, it is more likely that confounders can be partially avoided by studying well-defined post-infectious clinical entities rather than using the overly inclusive World Health Organization or similar definitions. Most studies of long COVID will inevitably emerge in older patient populations, but it is unlikely that this topic will escape the field of infant care regardless of how much less an impact it seems to have.

8. Treatment options

Large-scale well-designed placebo-controlled studies of one or more treatment modalities for infants are lacking. Inevitably, the propensity for less severe disease in pediatric patients is contributory. The acquisition of any such trial data for the infant subgroup would require large multicenter studies to attract sufficient patient numbers. The spectrum of virus-specific treatments for older children and adults includes antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, and plasma infusions. Similarly, solid data on the use of non-virus-specific disease modifiers, including corticosteroids, in infants are unavailable.

Various treatments and disease modifiers have been used considerably in pediatric age groups as suggested by observational studies [52,169,170]. Where specific antiviral chemotherapy has been administered, the frequency of included infants is relatively small [170,171]. Administration has been given largely on a compassionate basis with reference to some success in older age groups and in the vacuum of concrete trial data. More often, such treatments have been administered to older age groups with high-risk comorbidities, and interventions to treat other illnesses have already been established. There are many anecdotes in which different individual or combined treatments have been applied; however, these are insufficient to construct a sense of impact given the lack of control groups, even among retrospective studies. Whereas passive immunity would have theoretical justification, its application in infants lacks sufficient experience [172].

In the face of mild to moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection, the surgical management of other morbidities may be feasible [173].

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

This review is dedicated to the former tutelage from and collaboration with Dr. Chik H. Pai, then of the University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada.