Nonpharmacological interventions for managing postoperative pain and anxiety in children: a randomized controlled trial

Article information

Abstract

Background

Hospitalizations and surgical procedures are unpleasant for both children and their parents. Therefore, postoperative pain assessments and management are less commonly performed in younger children than in adults.

Purpose

To evaluate the effect of nonpharmacological interventions on postoperative pain and anxiety in children.

Methods

In this randomized controlled trial, 160 children were randomly allocated to experimental (n=80) and control (n=80) groups. The children in the experimental group received age-appropriate distraction interventions for 3 postoperative days along with standard care. Children in the control group received standard care only. Each child was assessed for pain using EVENDOL pain scale, while their anxiety was measured using the modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale. The Descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and repeated-measures analysis of variance were used to analyze the data.

Results

The children in the experimental group showed significantly decreased pain, anxiety, and physiological parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation) compared to those in the control group. Significant intergroup differences were noted in the mean and standard deviation values of the pain, anxiety, and physiological parameters.

Conclusion

The distraction interventions provided by nurses reduced the pain and anxiety levels and improved the postoperative recovery among children.

Key message

Question: What is the effect of nonpharmacological interventions on postoperative pain and anxiety among children.

Finding: Nurse-provided distraction interventions reduce pain and anxiety among pediatric surgical patients.

Meaning: The findings suggest that nonpharmacological interventions provided postoperatively to children reduce their pain and anxiety levels.

Introduction

Hospitalization and surgical procedures are an unpleasant experience to a child and their parents [1]. Children are more vulnerable to pain and anxiety due to lack of knowledge of procedures [2], lack of understanding of the procedures explained by the terms used and lack of pain management [3]. Every year more than a million children undergo surgical procedures and 50% of these children experience pain and anxiety in the perioperative period [4]. However, inadequate pain management delays postoperative recovery among children [5]. Also, increasing anxiety is associated with anticipating more pain and tolerating pain for less time [6]. Children in the pediatric surgical unit are operated for minor and major surgeries [7]. No matter what kind of surgery a child has, most of the postoperative pain can be reduced through appropriate pain assessment and interventions [8].

Postoperative pain assessment and management are less carried out among younger children as compared to the adults [9]. This results in increase in hospital stay, increased demand for analgesics and behavioral changes during postoperative period [10]. It is important to use age-appropriate pain and anxiety scales in the pediatric surgical unit [11]. Also, it is observed that pediatric pain assessment is not adequately practiced among younger children undergoing surgery due to lack of knowledge on standardized scales and lack of time [12].

Pharmacological and nonpharmacological interventions in a combination act as an effective measure to reduce postoperative pain and anxiety among children [13]. There are few studies which reported that therapeutic play [1,14-16], preoperative education [17-20], and guided imagery [21,22] are effective to reduce anxiety and pain among children.

Distraction is the most common type of cognitive-behavioral methods practiced among children [23]. It is an intervention that is often used to divert attention away from painful stimuli [24]. It is most effective when adapted to the child’s developmental and cognitive level [25]. There is lack of evidence on effect of age-appropriate distraction methods on postoperative pain and anxiety among younger children. It is necessary to develop age-appropriate distraction methods known to be effective in the postoperative period. Nurses play an important role in decision-making in identification of pain symptom recognition and follow-up pain relief. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of nonpharmacological interventions to reduce postoperative pain and anxiety among children.

Methods

1. Design and setting

The design adopted for the study was cluster randomized controlled trial. The schematic representation of the study design was developed according to Consolidated Standards of Reporting Clinical Trials (CONSORT) statement 2010 and is presented in Fig. 1. The study was conducted in a pediatric surgical unit of a tertiary care hospital in Karnataka, India. Every year approximately 200–300 pediatric surgeries are performed in this hospital. The children in the experimental group received a combination of distraction interventions and pharmacological treatment as interventions.

2. Participants

The participants included children aged 2–7 years and undergoing abdominal and urogenital surgeries; inpatient in the pediatric surgical unit for a minimum of 3 postoperative days (PODs); able to understand and speak Kannada or English and the child who is accompanied by mother for 3 PODs. The exclusion criteria were children undergoing cardiac, head and neck and orthopedic surgeries, mentally retarded and physically challenged and those children posted for emergency surgery.

3. Sample size

The sample size for the present study was calculated based on previous studies. Considering postoperative pain as primary outcome, the sample size of 160 (80 experimental and 80 control) was recruited. The power of 80% at a level of 0.05 significance and drop-out rate of 10% were considered.

4. Randomization and blinding

The participants in the study were randomly allocated to experimental and control group through week-wise randomization method. Since only one pediatric surgical unit was available, the entire pediatric surgery unit was considered as a cluster, and the weeks were randomized as experimental or control group for selecting the children in the study. The researcher was blinded on allocating the participants into the experimental and control group. Allocation of the children to the experimental and control group was done by the secondary investigator who was not directly involved in the recruitment of the children to the study. Researcher had taken an informed consent from parents and assent from the children. Due to the nature of trial the researcher was not blinded while data collection and follow-up.

5. Intervention

The children in the experimental group received the intervention for 3 consecutive PODs (starting from POD 1 to day 3). Age-appropriate distraction interventions along with the usual care (pharmacological treatment i.e., Morphine, Acetaminophen, Paracetamol based on type of surgery) were provided to the children in the experimental group. The nurse researcher offered the child an age-appropriate distraction kit which included distraction activities developed separately for 2–4 years and 5–7-years-old children. The main aim of the researcher was to divert the child’s attention from the painful stimuli. The kit for the children aged 2–4 years consisted of soft toys with different colours, book with pictures of animals, push and pull toys, breathing activities by blowing colourful feathers and pin wheel, role play game cards, simple blocks for construction, matching cards with different colours and pictures and colouring books. The distraction kit for the children aged 5–7 years were role play toys (kitchen set, doctor set), puzzle cards, drawing books and a magic book app that consisted of following items: counting the number of items in the images, finding the missing item, match the following and identifying the names in the images. The intervention was provided along with the mother for 3 postoperative days starting from the 1st POD. On POD 1, the distraction was provided once (after 6 hours of surgery). On PODs 2 and 3 the distraction was provided twice a day (morning and evening). Along with pain management interventions the mother was present with the child, monitoring of the child was done by the doctors and nurses and children received pain analgesics. The children in the control group received only the usual care (pharmacological treatment i.e., Morphine, Acetaminophen, Paracetamol based on type of surgery) and the mother being present with the child for 3 PODs, monitoring of the child was done by doctors and nurses and children received pain analgesics as per schedule. To prevent the cross-infection from the toys used by the children the kit was cleaned daily with alcohol-based solution (dettol) in the pediatric ward and soiled toys were exchanged with a new one. On POD 3, control group received a toy as a gift for participation in the study.

6. Outcome measures

The outcome measures of the study were pain, anxiety, and physiological parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation)

7. Postoperative pain

EVENDOL pain scale is a standardized instrument to measure the postoperative pain among younger children. This tool assesses the behavior of the child during postoperative period. The tool is composed of 5 subscales: vocal or verbal expression, facial expression, movements, postures, and interaction with the environment. The scale contains score from 0 to 3 for each item: 0 indicates=sign absent, 1=sign weak or transient, 2=sign moderate or present about half the time, 3=sign strong or present almost all the time. After obtaining the permission to use the tool in the study, researcher had checked for the reliability of the tool. Inter-rater reliability showed kappa 0.7–0.9. In the study EVENDOL scale was used for 3 PODs among the children who had undergone surgery. The pain measurements were taken by the researcher on 3 PODs. On POD 1, the pain measurements were taken after 2 hours of surgery and then continued for every fourth hourly. On PODs 2 and 3, pain was measured every seventh hourly. If the analgesic was administered during pain assessment through oral route pain was reassessed after 45 minutes, 10 minutes later if administered through intravenous route as per the guidelines provided in the scale.

8. Anxiety

Anxiety was assessed using mYPAS (modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale).It is a standardized tool developed by faculty of Yale University School of Medicine. The scale consists of 22 items divided into 5 subscales: activity, vocalizations, emotional expressivity, state of apparent arousal and use of parents. Each of the 5 categories has an individual score, ranging from the least anxious, to the most anxious behaviors. The higher the number the more the anxious behavior of the child. Reliability of the original tool ranged from 0.68 to 0.86. Researcher had assessed the reliability of the tool by using interobserver method. The reliability coefficient value was r=0.92 which shows that the tool was reliable. The anxiety measurements were taken on the day of admission of the child in a pediatric surgical unit and on POD 3 by the researcher. The behavior of the child in a pediatric surgical unit was observed and recorded.

9. Physiological parameters

The physiological parameters (heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation) were measured by Philips cardiac monitor (Intellivue MP5). Calibration of the monitor was done in the pediatric surgical unit. Researcher had assessed the reliability of the monitor by using interobserver method and agreement was 1 which shows that it is reliable. The physiological parameters were taken by connecting the probe to the child’s finger and the researcher recorded the measurements after the pain assessment. Child’s physiological parameters were also monitored for 3 PODs.

10. Ethical clearance

The trial was approved by the Institutional research committee. Researcher approached the participants, and a detailed Participant Information Sheet was given to the mothers before enrolling mother and child in the study. The sheet included details on the study procedure, intervention, benefits, and risk (none). The mothers were explained about the study by the researcher and informed consent from the mothers and assent from the children were taken. The protocol of this study was registered at the Clinical Trials Registry-India.

11. Data collection procedure

The data collection for the study was done from May 2019 to February 2021. After obtaining the permission from Institutional Ethical committee, cluster randomization was performed to allocate children to the experiment or control group. With randomization, every child had an equal chance of being assigned to the experiment or control group. Children who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included in the study. Informed consent from the parents and assent from the child were taken. Further allocation of participants to experiment or control group was done by a person who is not directly involved in the study. The children in both the groups were followed from admission to POD 3.

12. Data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and the percentage were used. The chi-square test, Fisher exact, and ‘t’ test were conducted to test the homogeneity of all baseline comparisons for the groups. Fisher exact value was considered if the frequency cells were lesser than 5. Repeated measures of analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to test the effectiveness of the intervention.

Results

1. Participant’s characteristics

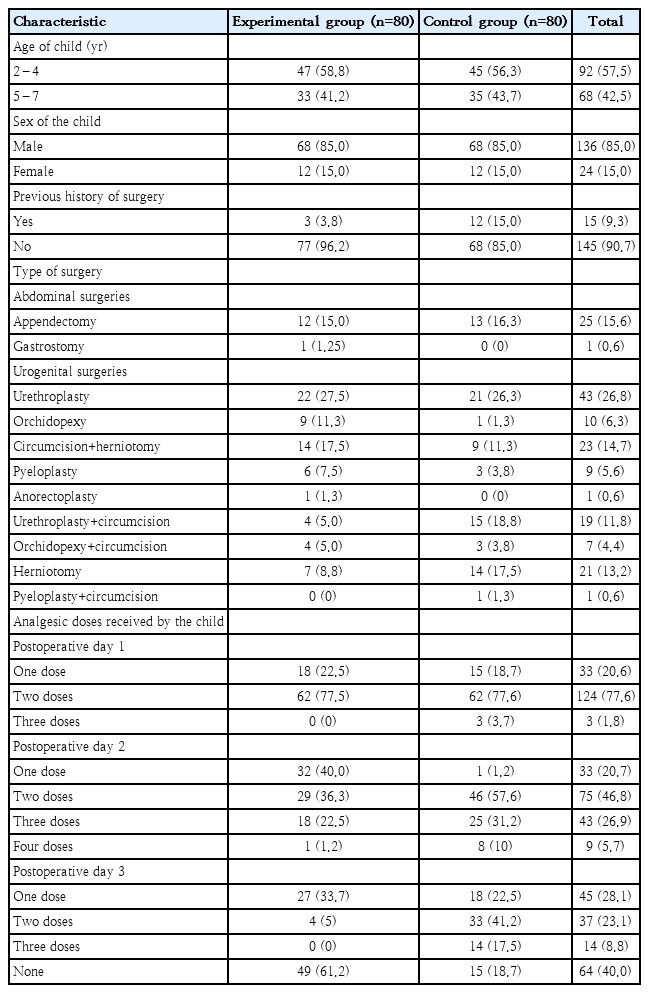

One hundred sixty children fulfilling inclusion criteria were randomly allocated to the experimental and control group (80 in each group). A CONSORT flow diagram of this trial is presented in Fig. 1. Most of the children (58.8% in the experiment and 56.3% in the control group) in the study were in the age of 2–4 years. During the data collection phase male children were operated more in number in both the groups. This is because most of the surgeries were conducted among males in the pediatric surgical unit. It was observed that 3.8% children in the experimental and 15% in the control group had previous history of surgery. It was found that 83.9% of the children in the experiment and 84.1% in the control group had undergone urogenital surgeries. Among them 27.5% of the children in the experimental and 26.3% in the control had undergone urethroplasty (Table 1).

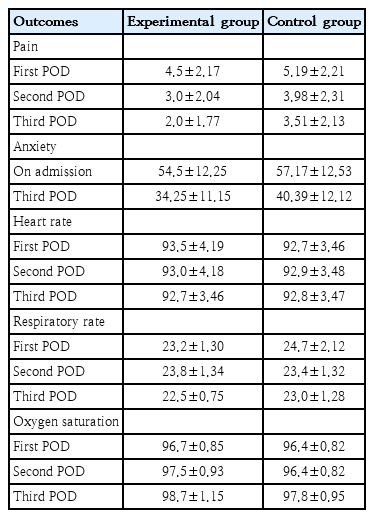

2. Effect of nonpharmacological intervention on postoperative pain

Mean pain score of children on POD 1 in the experimental group was 4.52±2.17 and control group 5.19±2.21 respectively. On POD 2, pain score in the experimental group was 3.0±2.04 and control group was 3.98±2.31 respectively. On POD 3, pain score in the experimental group was 2.0±1.77 and control group was 3.51±2.13 respectively. The children in the experimental group showed a considerable decrease in the pain compared to control group. The pain was reduced from PODs 1 to 3 in both the groups, but it is more evident in the experimental group on PODs 1 and 2 (Table 2).

Mean pain, anxiety, and physiological parameter values of the experimental versus control group (N=160)

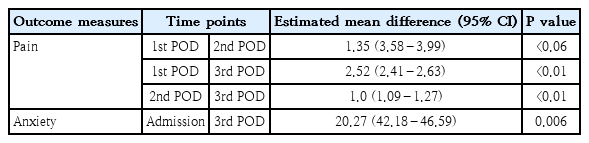

The analysis of repeated measures of ANOVA on effectiveness of nurse assisted distraction strategies on pain scores, which showed a greater statistically significant difference between the groups, F(1,158)=6,110.29, P<0.05, partial η2p=0.956. Within the experimental group analysis of repeated-measures ANOVA within the groups did not show a statistical significance F(1,158)=510.68, P=0.905, partial η2p=0.132 (Table 3, Fig. 2). The between group effect size of 0.956 represents a greater statistical significance in the experimental group and within group effect size of 0.132 shows moderate statistical significance. The findings prove that study findings decreased pain levels among children undergoing surgery. The data on mean difference and confidence interval of anxiety is described in Table 4.

Repeated-measures analysis of variance of inter- and intragroup differences in pain, anxiety, and physiological parameter values (N=160)

Plot of estimated mean marginal pain at different time points among children in the intervention versus control group. POD, postoperative day.

3. Effect of nonpharmacological intervention on Anxiety

The decrease in anxiety mean scores from admission to POD 3 in the experimental group was greater with the mean difference of 20.3 whereas in control group the mean difference was 16.8. The decrease in anxiety scores in the experimental group was much higher in the posttest measures as compared to the control group. There was reduction in anxiety scores in the control group also, but it was minimal when compared to the children in the experimental group (Table 2).

The analysis of repeated measures of ANOVA between experimental and control group showed a statistical significance, F(1,158)=347.6, P<0.006, partial η2p=0.957. Within the experimental group analysis of repeated-measures ANOVA showed a higher statistical significance F(1,158)=306.6, P=0.101, partial η2p=0.660. The between group effect size of 0.957 represents high statistical significance between the 2 groups and within group effect size of 0.660 represents moderate statistical significance. The findings prove that intervention decreased anxiety of children undergoing surgery (Table 3, Fig. 3). The data on mean difference and confidence interval of anxiety is described in Table 4.

4. Effect of nonpharmacological intervention on Physiological parameters

The mean heart rate observed from 1st, 2nd, and 3rd POD in the experimental group was (93.5±4.19, 93.0±4.18, 92.7±3.46) and in control group (92.7±3.46, 92.9±3.48, and 92.8±3.47) respectively. The mean respiratory rate in the experimental group was (23.2±1.30, 23.8±1.34, and 22.5±0.75) and control group was 24.7±2.12, 23.4±1.32, and 23.0±1.28. The mean oxygen saturation in the experimental group was (96.7±0.85, 97.5±0.93, and 98.7±1.15) whereas in the control group was (96.4±0.82, 96.4±0.82, and 97.8±0.95) (Table 2).

The repeated-measures ANOVA on physiological parameters (heart rate) between the groups showed a higher statistical significance, F(1,158)=10.45, P<0.005, partial η2p=0.998. Further, within the experimental group analysis of repeated-measures ANOVA had shown moderate statistical and clinical significance with F(1,158)=15.44, P<0.115, partial η2p=0.089. The repeated-measures ANOVA on physiological parameters (respiratory rate) between the experimental and control group showed a higher statistical significance, F(1,158)=19.52, P<0.005, partial η2p=0.992. Further, within the experimental group analysis of repeated-measures ANOVA had shown moderate statistical and clinical significance with F(1,158)=19.0, P<0.005, partial η2p=0.107. The repeated-measures ANOVA on physiological parameters (oxygen saturation) between the experimental and control group showed a higher statistical significance, F(1,158)=24.4, P<0.005,partial η2p=0.201. Further, within the experimental group analysis of repeated-measures ANOVA had shown moderate statistical and clinical significance with F(1,158)= 31.0, P<0.005, partial η2p=0.154. The children in the experimental group had shown a significant improvement in the heart rate, respiratory and oxygen saturation during all measurements as compared to the control group (Table 3, Figs. 4–6).

Plot of differences in estimated heart rate at different time points among children in the intervention versus control group. POD, postoperative day.

Plot of differences in mean estimated respiratory rate at different time points among children in the intervention and control group. POD, postoperative day.

5. Effect of nonpharmacological intervention on postoperative analgesic use

On POD 1, 77.5% children in the experimental group and 77.6% in the control group received 2 doses of analgesics. However, there are 3.7% children in the control group who received 3 doses of analgesics. On POD 2, 40% children in the experimental group received 1 dose of analgesic. Whereas 57.6% children in the control group received 2 doses of analgesics. On POD 3, 33.7% children in the experimental group received one dose of analgesic and 61.2% children did not receive any analgesics. Whereas, in the control group 41.2% children had received 2 doses of analgesics. The findings show that on 3 PODs children those received distraction intervention received less doses of analgesics as to those who did not receive the intervention.

Discussion

Anxiety and postoperative pain are the common problems that delays postoperative recovery among children [2]. There has been a significant amount of research on children's anxiety because of hospitalization, which includes unpleasant and scary medical procedures with or without preparation [26]. However, to provide the best possible care for these children, an assessment of how best to organize the care is required. Considering sustainable development goals health and well-being is a priority for all the ages researchers had taken up a study to determine the effect of distraction interventions in reducing anxiety and pain in children undergoing surgery. The findings of the study showed that the intervention group's outcome measures improved more than those who received standard care, which answered the research question favorably. There was significant reduction in anxiety and pain scores among children in the experimental group. Also, there was reduction in anxiety and pain scores in the control group but statistically it was not significant.

In this study, the experimental group had a significantly lower level of anxiety than the control group. Previous study has found that distraction interventions dramatically reduce anxiety in children undergoing surgery, which is consistent with current findings. Nonpharmacological therapies to alleviate preoperative anxiety in children were found to be beneficial in a Cochrane study [27]. Yip et al. [28] found that playing a handheld video game reduces children's anxiety and reduces postoperative complications in a systematic order. Even though children undergoing surgery have a higher level of anxiety than adults, there is little evidence to support distraction interventions for perioperative anxiety.

When compared to the control group children, the experimental group had a considerable drop in pain levels. Previous studies on the impact of distraction on postoperative pain in children have found similar results. A study by Olsen et al. [29] reported that among younger children adjunct to traditional postoperative pain management, nonpharmacologic distraction intervention is indicated. Also, a systematic review by Davidson et al. [30] reported that psychological interventions may be effective in reducing short-term postoperative pain among children. Even though there were studies with nonpharmacological interventions the interventions were either provided in the preoperative or postoperative period. There was inconsistency in the interventions provided in the given studies. Studies related to the effect of distraction intervention on postoperative pain are limited to draw the conclusion. However, from the present study findings we found that distraction interventions provided from PODs 1 to 3 among younger children are effective to reduce pain and anxiety.

According to the study results, health workers should be trained in the use of distraction interventions. The experimental and control groups had substantial differences in anxiety and pain scores. Because the distraction intervention is very minimal expensive and simple to deploy, they can be quickly introduced in pediatric surgical units to make a child's hospital stay less traumatic and more memorable. Parents can be trained about distraction strategies, which will allow them to participate in their children's care. We also believe that if distraction interventions are used by the right person at the right time, there will be a noticeable effect in the child's treatment. The strength of our study is we included a total of 160 children and there were no dropouts. To make it clear that distraction intervention was effective this was a randomized controlled study that identified the effect of distraction intervention only with combination with standard care. A combination of intervention was not applied as it is difficult to draw the conclusion on which intervention was effective. To prove the effect of intervention physiological parameters were also assessed along with pain measurements adds as a strength of this study. The limitation of our study is it was conducted in a single setting and blinding of researcher was not possible, however researcher was blinded on allocation of the children to the experimental and control group. Pain and anxiety scales were validated scales that observes the behavior of the child. Future studies can focus on the limitations of our study and more randomized controlled trials can be carried out on the effect of distraction interventions of different age groups. Also, the effect of distraction on preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain can be studied separately to draw a conclusion.

1. Implications for education

Distraction is an effective method for children to cope with pain and anxiety. Nurses should be better informed on different sorts of distractions and how to use them in different situations. Nurses should be cautious when employing distraction or any other nonpharmacological strategy to treat anxiety and moderate-to-severe pain. To effectively manage pain and anxiety, both pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments must be employed. Pain management courses should be included in the nursing undergraduate curriculum in low income and developed countries. This can be used as a starting point for incorporating distraction and other nonpharmaceutical treatments into nursing care. Nurses must also be educated on the latest research results on distraction and other pain management strategies through educational programmes. These programmes should also emphasize the development of skills related to distraction and the encouragement of nurses to constantly document their nursing interventions provided for the children to reduce pain and anxiety.

2. Implications for research

Based on the findings of this study, it appears that distraction intervention is effective to reduce pain and anxiety among children undergoing surgery. Furthermore, future study should examine the efficiency of various distractions such as active versus passive distractors as well as the child’s preference of distraction. Additionally, the impact of distraction on major surgeries should be assessed. Furthermore, research studies to evaluate parent satisfaction with pain management, both pharmacological and nonpharmacological, are required. Nurses should also investigate the use of distraction interventions that children can utilize without the presence of a nurse. Also, further studies can explore the effect of music, phone games, and deep breathing exercises as a distraction technique among children in the pediatric surgical unit.

In conclusion, distraction interventions provided by nurse helps to reduce anxiety and pain among pediatric surgical children. The findings of this study add to the growing body of knowledge about nonpharmacological therapies for children who have undergone surgery. These measures can be implemented based on these encouraging findings to lessen children's pain and anxiety and promote positive postoperative recovery.

Nurses in the pediatric surgical unit can practice the distraction interventions among children to alleviate pain and anxiety. The children in the pediatric surgical unit can receive a combined pain management treatment (pharmacological and distraction interventions). A pain management nurse can be appointed who can extensively focus on pain assessment and management of the children in the postoperative period.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study was supported by Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), Manipal, Karnataka, India through Dr TMA Pai Scholarship for pursuing full time PhD in Nursing.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: EGM, MSP; Formal Analysis: EGM, MSP, VG; Investigation: EGM, MSP; Methodology: EGM, MSP, VK, DN, MK, VG, ACB, BSN, AG; Project Administration: EGM, MS; Writing– Original Draft: EGM, MSP, ACB; Writing–Review & Editing: EGM, MSP, VK, DN, MK, VG, ACB, BSN, AG

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all the children and mothers for participating in the study.