Characteristics of temper tantrums in 1–6-year-old children and impact on caregivers

Article information

Abstract

Background

Temper tantrums are common behavioral difficulties in children. Although they are generally considered a normal part of development, certain characteristics— such as aggression, prolonged duration, and frequent occurrences—have been linked to psychological issues and can negatively impact both the child and their caregivers.

Purpose

To study the prevalence and characteristics of temper tantrums in children aged 1–6 years at daycare and in kindergarten in Thailand as well as the impact of problematic and nonproblematic tantrums on their caregivers’ emotional well-being.

Methods

This cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted in 2021. The main caregivers of the participants completed self-reported questionnaires that collected their demographic information and the temper tantrum characteristics and impacts on the caregivers’ emotions.

Results

Data from 211 children were included in this study. The mean child age was 4.4±1.2 years. Two hundred one parents (95.3%) reported that their children had at least one tantrum behavior, of which verbal were the most common (94.5%). One hundred and 11 children (55.2%) had tantrums defined as problematic: exhibiting aggressive physical behavior, duration >15 minutes, frequency >3 days/wk. The mean emotional burden scores of the children’s problematic and nonproblematic temper tantrums on their parents were 23.3±8.4 and 17.7±8.3 (maximum, 55; P=0.001), respectively, showing a statistically significant difference.

Conclusion

Tantrums are common in children aged 1–6 years, but their expression varies. Problematic tantrums were reported for approximately half of the children and significantly impacted their caregivers’ emotions. Therefore, children with problematic tantrums and their families should receive assistance.

Key message

Question: What are common tantrum behaviors in pre school children, and how frequently are problematic be haviors observed? Do problematic tantrums have a differ ent emotional impact on caregivers compared to typical tantrums?

Finding: Temper tantrums are common in preschool children, and verbal tantrums are the most common type.

Meaning: Problematic tantrums, defined as tantrums exhibiting aggressive physical behavior, long duration (>15 minutes), or frequent occurrence (>3 days/wk), signi f icantly affected caregivers’ emotions.

Graphical abstract. Characteristics of temper tantrums in 1–6-year-old children and impact on caregivers

Introduction

Temper tantrums are behaviors that children use to show displeasure, such as screaming, crying, shouting, stamping, kicking, hitting, writhing on the floor, throwing or destroying things, and hurting themselves, to vent anger or frustration [1-3]. Temper tantrums are the most common behavioral difficulty among children from toddler to preschool age [4]. They usually begin at 12 to 18 months of age, peak at 2 to 3 years, then gradually decrease until they disappear by 4–5 years of age [5]. The prevalence of temper tantrums among children has been reported worldwide, ranging from 30% to 91% [1,6-9]. Reasons for the wide range of prevalence may be due to different definitions and the different ages of children from study to study. A study in Thailand on the prevalence of temper tantrums among kindergarten children found that 33.5% had temper tantrums [8].

Temper tantrums are often seen as normal behavior in young children, who still need to learn self-control. Tantrum behaviors can be expressed in many ways. Verbal expressions are the most common tantrum behaviors, and are often classified as mild form; examples of these behaviors include crying, shouting, and screaming [6,7]. Physical expressions may be expressed in a way that is not harmful (such as stiffening, writhing on the ground) or harmful (such as kicking, hitting, throwing things, breaking possessions, or self-hurting).

Parents are often advised that such behavior will improve as the child grows older, which is true in most cases. However, some characteristics of tantrums have been found to be associated with psychological problems and have a negative effect on the emotional well-being of parents. Based on a review of previous research, 3 characteristics of tantrums that were atypical or more severe than usual and had evidence of negative effects are: aggressive tantrums, long duration and tantrums that occur frequently [5,6,10-12]. First, harmful or aggressive tantrums were found to be associated with adjustment and psychological problems. A longitudinal study revealed that an aggressive behavioral profile was associated with both externalizing and internalizing symptoms in children when followed one year later [5]. Another study found that preschool children with emotional problems were more likely to display aggressive tantrums than healthy children, which is described in detail as follows: aggressiveness towards others or destruction of belongings is associated with disruptive behavioral problems, whereas self-harming is associated with mood problems [11]. Aggressive tantrums were found less frequently than nonaggressive tantrums; only 23% of children display harmful tantrums [6]. Second, tantrums with long duration reflected that children have difficulty managing their frustrating emotions. Previous studies have found that longer tantrums are associated with internalizing symptoms, disruptive behavioral problems and also predict later adjustment problems [5,6,13]. Typical durations of tantrums usually in the range of 1.5–20 minutes [7,14,15]. Potegal et al. [15] reported the median duration of tantrums was 3 minutes, and the average duration of tantrum increased with age, from around 2 minutes for 1-year-olds to 4 minutes for 4-year-olds. Not many children had tantrums for a long time; only 2%–6% of children have tantrums for more than 30 minutes [5,14]. Third, frequent tantrums indicated that children are easily provoked to become frustrated. Frequent tantrums are also found in children with emotional problems more than in healthy children. Children with depressed mood and disruptive behaviors had more frequent tantrums [13]. and children with frequent tantrums were later associated with externalizing symptoms [5]. Studies on the frequency of tantrums reported that around 75% of children had tantrums less than 3 times per week, a small minority of children had a tantrum more than 3 times per week and less than 10 % had a tantrum every day [6]. The frequency of tantrums decreases as the child grows.

Efforts have been made to isolate normal tantrums from problematic tantrums because the latter should be further assessed and early intervention provided. Based on a review of research as mention previously, we defined 3 characteristics of tantrum as problematic tantrums; aggressive physical tantrums (self-harming, harming others, and destroying things), duration more than 15 minutes, and frequency of more than 3 times/wk. We hypothesized that while parents of children who express typical temper tantrums are likely to handle it, parents of children with problematic tantrum children are more likely to experience anxiety, stress, and feel incapable of managing such behaviors.

This research aims to study characteristics of tantrum behaviors in Thai children aged 1–6 years. In addition, we also want to explore the impact of problematic tantrums on caregivers, in terms of mood and feelings.

Methods

This research was a cross-sectional descriptive study, conducted in 2021 at the Early Childhood Development Center (daycare) and Kindergarten School of Thammasat University, Thailand. The children who attend to the childhood development center were ordinary children age 3 months to 3 years old and children who joined the Kindergarten School were also children with typical development age 3 to 6 years old; however developmental disorders may be detected in these children later on. The target population was children aged 1–6 years old, whose parents agreed to participate. The exclusion criteria were: children who had medical problems, such as heart disease, epilepsy, chronic lung disease, neurological disease; children who had been diagnosed with developmental disorders including autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, global developmental delay; children with hearing or visual impairment. Ethical approval was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Thammasat University, Faculty of Medicine: project number MTU-EC-PE-0-209/63.

After consent to participate in the research project, parents who were the main caregivers self-administered questionnaires via paper-based form or electronic form, depending on the convenience of the parents. The questionnaires consisted of 3 parts including demographic data collection, characteristics of temper tantrums, and impact of temper tantrums on the emotions and feelings of the caregivers.

The demographic data collected gender, age, children’s grade, parental education, family monthly income and information of respondents including sex, age, relationship with children. The questionnaire on tantrum characteristic asked primary caregiver if, in the past 2 months, their child exhibited any of the following tantrum behaviors: crying loudly, screaming or yelling, arguing, swearing, stamping, writhing on the floor, self-harming (e.g., pulling hair, scratching face, punching self, head banging), harming others (such as hitting, pinching, scratching, shoving others), and throwing things which resulted in damage to items or injury to others. It also asked about the duration and frequency of temper tantrum; child temper tantrums usually last less or more than 15 minutes, and whether temper tantrums happen more or less than 3 times a week. Base on a previous study [5-6,10-15], we defined the operational definition of problematic tantrums in this study as children exhibiting one of the following tantrum behaviors: aggressive physical tantrums (self-harming, harming others and destroying things), duration more than 15 minutes, and frequency more than 3 times/wk.

The questionnaire on the effects of tantrum behavior on parents' emotions and feelings was a newly developed questionnaire designed based on the concept of caregiver’s burden [16,17]. We conducted a literature review for an appropriate questionnaire assessing the effects of tantrum on parents' feelings. Unfortunately, we did not find a suitable questionnaire for using in young children and in context of our setting. Thus, we decided to develop a new questionnaire. It was a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire, in which responders specify their level of agreement to a statement, typically in 5 points: (1) strongly disagree, (2) disagree, (3) neither agree nor disagree, (4) agree, (5) strongly agree. Examples of the questions are: “You feel stressed because you have to deal with the child's temper tantrum” and “You feel you should be able to better manage tantrum behaviors of your child.” For content validation, the original 12-item questionnaire was reviewed by 5 child development experts, including developmental and behavioral pediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, and a developmental psychologist. The experts were asked to rate instrument items in terms of appropriateness and relevance to the theory. The item content validity indexes (I-CVI) were calculated and found to be in the range of 0.4–1.0. One question which had an I-CVI of 0.4 was removed, so the final version of questionnaire consisted of 11 questions and the scale-level CVI was calculated by averages of the item-level CVI method, and found to be 0.84 which is in an acceptable range. The internal consistency was assessed to determine the reliability of the questionnaire and the Cronbach alpha was 0.89 for the population in this study.

Descriptive data was reported in number, percentage, mean and standard deviation. T-test were used to compare the impact on caregivers between typical tantrums and problematic tantrums. Regression analysis were used to calculate impact of each component of problematic tantrums on the caregiver’s burden score.

Results

From a total number of 428 children at the kindergarten school and 95 children at the Early Childhood Development Center, there were 219 (51%) and 17 parents (18%) from the daycare and kindergarten agreed to participate in the project and completed the questionnaire. Nine children (1.56%) had been previously diagnosed with developmental disorders, and 6 children with medical conditions were excluded from the study based on the exclusion criteria, and an additional 10 participants were excluded because their parents did not complete the questionnaire, making their responses unanalyzable. As a result, 211 children were included in the study.

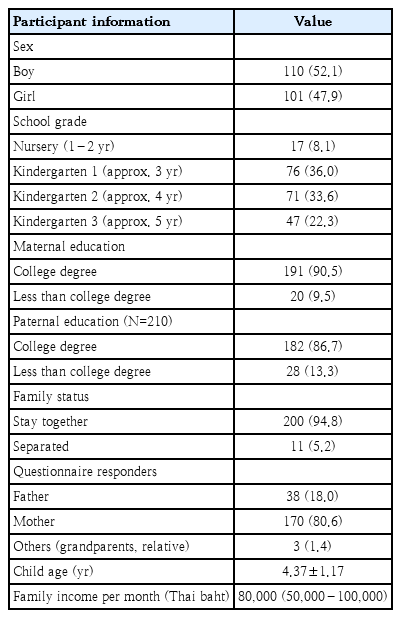

The mean age of children was 4.4±1.2 years old; 112 of them (50.7%) were boys. Most of their parents had college degrees. The majority of respondents were mothers, accounting for 170 (80.6%) of the participants. Demographic data of children and respondents are shown in Table 1. Comparing the demographic data of the problematic tantrums group and the nonproblem tantrums group revealed no differences in factors regarding gender, age, maternal education, paternal education and parents' marital status.

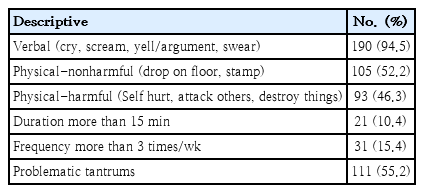

Data from the questionnaire about children’s tantrum revealed that almost all of the children, 201 (95.3%), exhibited at least one of the following tantrum behaviors in the past 2 months: crying, screaming, yelling/arguing, swearing, stamping, writhing on the floor, self-harming, violent towards others, or destroying property. Our study found that 28.9% of children displayed one tantrum behavior, 24.6% showed 2 behaviors and 24.2% displayed 3 behaviors of tantrums. The remaining 17.5% exhibited 4 or more tantrum behaviors. Among tantrum behaviors, crying was the most common (58.3%), followed by stamping (42.7%) and screaming, yelling/arguing (35.6%). Among children who exhibited any tantrum behaviors, 190 children (94.5%) displayed verbal tantrum behaviors, and 93 children (46.3%) demonstrated aggressive physical behaviors. Throwing or destroying objects was the most common aggressive action, occurring in 24.3% of cases. According to the operational definition of problematic tantrums, 111 children (55%) were classified as having problematic tantrums. This classification may be due to aggressive behaviors that endangered themselves or others, as well as tantrums that were prolonged or frequent. Among these, 5 children (2.4%) exhibited all 3 elements of problematic tantrums. The prevalence of tantrums and additional details are shown in Table 2.

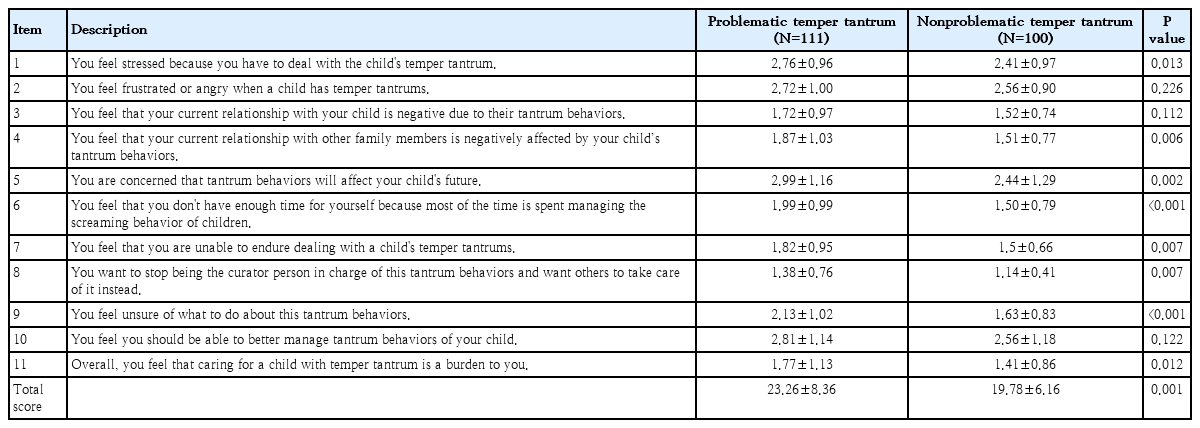

Table 3 revealed a higher mean total score of emotional impact from tantrums in the problematic tantrum group compared to the nonproblematic group, 23.26 versus 19.78, which was statistically significant. Most of the item scores were also significantly higher. We defined parents who rate their emotional impact as “agreed” or “strongly agreed” (score 4 or 5) as being greatly emotionally impacted, as shown in Fig. 1. Results showed that the number of parents scoring their child’s tantrum at the level of 4 or 5 ranged from 1% to 29% for each question. The number of parents in the problematic tantrums group who were greatly emotionally impacted was significantly higher for the following questions: feeling stressed, feeling irritated, feeling angry, feeling that it affects the relationship with the child, and being concerned that tantrums will affect their child's future.

Comparison of emotional impacts reported by caregivers of children with problematic versus non-problematic tantrums.★, statistical significant.

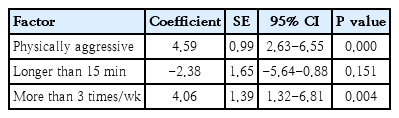

Considering the factors that compose a problematic tantrum, we performed multivariate analysis to identify the effect of each component on the total tantrum score. We found that aggressive physical tantrums and frequent tantrums significantly affected the total score of impact on parents' emotions, while longer duration did not significantly affect the total mean score (Table 4).

Discussion

This study found that temper tantrums were common behavior in Thai children aged 1–6 years; 95% of preschool children exhibited some form of tantrum behavior during a two-month period. Analyzing the details of tantrum behaviors revealed that most temper tantrums were verbal form: crying, screaming, shouting, arguing and swearing. Among these, crying was the most common tantrum behavior, consistent with previous research [1,5,7]. Physical expressions were found in many children, with 46% of children showed aggressive physical tantrum, similar to Carlson study, which found that 45%–49% of children in the community displayed severe tantrum behavior [18]. In terms of the duration and frequency of tantrums, only 10% of children in this study had tantrums lasting longer than 15 minutes, and 15% had tantrums more than 3 times per weeks. This supports the notion that tantrums lasting more than 15 minutes and occurring more than 3 times per week are atypical indicate severe or problematic tantrums.

Regarding the effects of tantrums on parental emotions, the proportion of parents who believed their child's tantrum greatly affected them—by causing stress, angry or frustration, worsening their relationship with the child, and concerns about their child’s future—was higher in the problematic tantrum group and statistically significant. Additionally, the mean score on the emotional impact of the tantrum questionnaire was significantly higher for the problematic tantrum group compared to the nonproblematic group. Previous studies have found that each of the 3 components of problematic tantrums affect parents’ emotional status and effective parenting. Aggressive tantrums could make parents angry or, conversely, fearful of their child's behavior [19]. A study in toddlers revealed that when children expressed disruptive behaviors in frustrating situations, their parents felt lower self-efficacy and increased stress [12]. Strong reactions from children made it harder for parents to recover from undesirable emotions and affected positive parenting [20-22]. When parents resorted to negative parenting, such as using more power assertion or coercion, it increased the severity of tantrums [23,24]. Long tantrums can also made parents feel incompetent because they are difficult to manage [25]. On the other hand, parents who manage tantrums inconsistently may cause tantrums to last longer than usual [6]. Similarly, frequent tantrums inevitably made management more difficult, affecting parental self-competency in the same way as long tantrums [25].

Since the definition of a problematic tantrum consisted of 3 components—aggressive physical tantrum, long duration, and high frequency—we wanted to explore which components accounted for the high scores. Multivariate analysis showed that aggressive physical tantrums and high frequency were factors associated with higher mean score, while duration did not take an effect. The impact of aggressive tantrum behavior on parents' mood aligns with previous research [1]. Aggressive tantrums tended to make parents nervous, frustrated, or unsure of how to deal with them. In Thai culture, when a child exhibits aggressive behavior, it is often seen as a result of poor parental upbringing. Frequent tantrums caused parents to deal with such behavior often.

An interesting finding from the questionnaire was that approximately one-quarter of all parents worried that tantrum behavior would affect their children's future, and felt they should have handled the tantrum behavior better. If health care providers had the opportunity to discuss the natural course of tantrums with parents, emphasizing that tantrums will likely improve as the child grows older, it could help alleviate parents' concerns. Additionally, discussing how parents manage tantrum behaviors and providing advice on proper management methods could help parents gain more confidence in managing tantrum behavior.

We recognize limitations in this study. First, this research was conducted in a small area in Thailand, therefore the study may not have a diverse population. Perceptions of tantrums may vary across culture, so applying these results to other areas may require further study. Secondly, the response rate of participants was limited. Shortly after starting the project, schools had to be closed due to the coronavirus disease 2019 situation, making it difficult to contact interested parents or collect additional questionnaires. We acknowledge that the lower response rate could cause selection bias; for example, parents who participated may have had concerns about tantrums, resulting in a higher reported prevalence than in actuality. Finally, we did not find the appropriate questionnaire for evaluating emotional impact of tantrums on caregivers in young children. Thus, we developed a new questionnaire for this study. Although the questionnaire was validated in term of content validity and internal consistency for the study population, we understand it may not as reliable as standardized questionnaire, and the further validation is needed for other populations.

Despite several limitation, this research should help expand knowledge about tantrum behavior in children and highlight that problematic tantrum behaviors had more significant emotional effect on parents, if a child is found to have problematic tantrums, assessing and addressing parent’s concerns about such behavior is essential, and further assistance should be provided to children and families to manage tantrum problems appropriately.

In conclusion, almost all children aged 1–6 years exhibited some form of tantrum behavior, with varied expressions of these behaviors. Problematic tantrum behaviors were found in about half of the children and significantly impacted their caregivers’ emotion. Therefore, children with problematic tantrums and their families should be provided with appropriate support and assistance.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or notforprofit sectors.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: CI, PW, HS; Data curation: PW; Formal analysis; SP, CI; Methodology: PW, IC; Project administration: PW, CI; Writing original draft: PW; Writing review & editing: CI, HS

Acknowledgements

This research would not have been possible without the contributions of the participating families and the support from staffs of the daycare and the school. We would like to acknowledge Sam Ormond, from the Clinical Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University for editorial assistance in improv ing the English in this manuscript.