Practical concepts and strategies for early diagnosis and management of eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders in East-Asian children

Article information

Abstract

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) are emerging as significant concerns in the Korean pediatric population and transitioning from rare to more commonly diagnosed conditions. This review discusses the increasing prevalence of EGID among children and adolescents and highlights the complexities involved in its diagnosis and management. This review begins with a thorough examination of the diverse clinical presentations of EGIDs in Korean children, with a special focus on common gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. Additionally, we explored extraintestinal manifestations, including growth failure, malnutrition, and associated allergic comorbidities, highlighting their importance in the clinical landscape of EGIDs. Because of its subtle and overlapping symptoms with those of other gastrointestinal disorders, EGID is frequently underdiagnosed. Addressing this challenge requires maintaining a high index of suspicion and employing a comprehensive diagnostic approach to differentiating EGID from functional gastrointestinal disorders and other inflammatory or systemic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease. The optimal management of EGID requires a collaborative multidisciplinary strategy that includes dietary management, regular monitoring, and tailored medical interventions. This review emphasizes the importance of proactive patient and caregiver education and regular follow-ups to improve long-term outcomes in affected children. Enhanced awareness among healthcare providers and better educational resources for families are critical for the early identification and effective management of EGID among pediatric patients.

Key message

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) often coexist with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) and other IgE or non-IgE mediated GI diseases. Diagnosing EGIDs requires a high index of suspicion and a comprehensive approach to differentiate them from conditions like inflammatory bowel disease. Tests such as fecal calprotectin and biopsies aid in severe cases. Maintaining a food diary helps identify triggers for long-term elimination. Awareness and education are key to effective management.

Graphical abstract. Differentiation of non-EoE EGID from FAP and IBD based on main symptoms. In children with chronic gastrointestinal symptoms (GI Sx), it is essential to differentiate between EGIDs, IBD, and severe FAP, even in cases of pronounced or minimal eosinophilic infiltration, to avoid premature diagnostic conclusions. EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EGID, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder; FAP, functional abdominal pain; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; CVS, cyclic vomiting syndrome; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; FD, functional dyspepsia; FPIE, food protein-induced enteropathy; FPIES, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome; FPIP, food protein-induced proctocolitis; RAP, recurrent abdominal pain.

Introduction

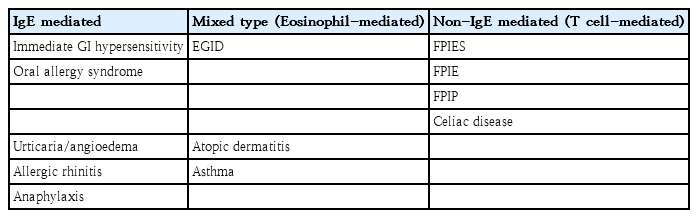

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) are a group of chronic inflammatory disorders primarily affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In this review, we will review and discuss EGIDs with a particular focus on the occurrence of non-eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) EGIDs in Korean children. However, the natural course and long-term outcomes of non-EoE EGIDs are poorly understood. Non-EoE EGIDs can present with different clinical symptoms, and some patients may exhibit skin, respiratory, or systemic allergic symptoms in addition to GI symptoms (Table 1). Food allergies generally involve immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated immediate reactions; however, other reactions manifesting as GI symptoms are related to non-IgE mechanisms, particularly those involving T cells and eosinophils. Patients with EGIDs may also present with allergic conditions such as anaphylaxis or food protein-induced enteritis, leading to these symptoms [1].

Atopic diseases are commonly observed in pediatric patients with EGIDs, with approximately half to three-quarters of them experiencing asthma, dermatitis, or food allergies [2]. While skin and respiratory allergies are generally IgE-mediated, GI allergies in infants are non-IgE-mediated, making it difficult to identify the causative foods using IgE tests such as multiple allergen simultaneous test (MAST) or UniCAP test [3].

This review article comprehensively introduces non-EoE EGIDs based on the latest guidelines from European and North American Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition societies and explains practical issues through case studies [4]. It offers an accessible approach to diagnosing and managing non-EoE EGIDs and presents interesting cases that raise unresolved questions regarding EGIDs. EGIDs have historically been referred to as GI diseases or disorders, but current guidelines classify them as GI disorders. The term "disorder" refers to an abnormal condition ranging from functional abnormalities to symptoms of disease and GI abnormalities.

High index of suspicion is key

Allergic diseases are common in infants and young children. However, if their symptoms are accompanied by chronic GI symptoms, non-IgE-mediated allergic enteritis or EGIDs should be considered. A high level of suspicion is required for the early diagnosis of EGIDs, even in the absence of an associated allergic disease.

1. Chronic diarrhea

A 7-month-old infant presented with chronic diarrhea accompanied by severe atopic dermatitis. Chronic diarrhea in infants may be difficult to diagnose as food protein-induced enteropathy (FPIE) unless a food allergy is suspected.

Prolonged diarrhea in infants can lead to a vicious cycle, with postinfectious chronic diarrhea and the subsequent development of lactose intolerance and FPIE. In infants with chronic diarrhea and severe atopy, prolonged exposure to milk proteins and aggravated foods may lead to FPIE. Differentiating FPIE, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), and food protein-induced proctocolitis (FPIP) from EGID is crucial. FPIE, FPIES, and FPIP are primarily observed in neonates and young infants. Although FPIE has been well-recognized by pediatricians in Korea for over 30 years, clinicians must suspect the disease to avoid misdiagnosing it as simple enteritis [5]. In particular, when necrotizing enterocolitis occurs in full-term neonates, FPIES should be suspected [6].

2. Chronic abdominal pain

Twenty years ago, a 4-year-old child presented with severe recurrent abdominal pain (RAP) that started at 1 year of age and was accompanied by sweating, groaning, and sudden lethargy after vomiting. Despite visiting 6 tertiary hospitals and undergoing gastroscopy, colonoscopy, electroencephalography, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) or CT enterography over 3 years, a diagnosis could not be made. A thorough medical history revealed that the child had scratched his body before severe symptoms occurred and developed atopy after eating snacks. Upper-GI endoscopy and a biopsy confirmed EGID due to heavy eosinophilic infiltration in the duodenum, and the child fully recovered after dietary management. Chronic RAP in children can be difficult to assess as EGID unless a food allergy is suspected as the cause.

This case emphasizes the need to consider severe EGIDs in children presenting with extreme abdominal pain requiring prompt evaluation and treatment. Diagnosing EGIDs may be relatively straightforward if all childhood GI food allergies are accompanied by severe allergies, or if all EGIDs can be diagnosed using biomarkers. However, diagnosing EGIDs in the absence of other allergic symptoms is often challenging unless suspected from the beginning. Thus, recognizing severe GI symptoms as potential indicators of EGIDs is crucial.

Review of non-EoE EGIDs

This review's content follows the structure of the guidelines and was based on its recommendations and statements.

1. Definition, epidemiology

1) Definition of non-EoE EGIDs

Non-EoE EGIDs, which include chronic inflammatory GI disorders other than EoE, are characterized by GI symptoms and prominent eosinophilic inflammation of the GI tract with no identifiable secondary causes [4].

Historically, these conditions have been referred to by various names, including allergic (gastro)enteritis, allergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis, atopic GI disease, and FPIE. The nomenclature has now been standardized to include non-EoE EGID. Food allergies are often classified as food hypersensitivity. However, it is crucial to distinguish between food hypersensitivity (intolerance) and food allergies for proper patient and caregiver education. Food allergies involve immune reactions to food proteins (e.g., milk proteins and gluten), whereas food intolerance refers to GI symptoms triggered by specific foods (e.g., lactose and wheat) and additives.

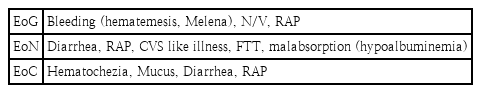

2) Recommended terminology for non-EoE EGIDs based on GI tract involvement

According to recent international nomenclature consensus, the term “Eo” (for eosinophilic) is prefixed to the specific organ affected. For example, EoG (gastritis), EoD (duodenitis), EoJ (jejunitis), EoN (enteritis), EoI (ileitis), and EoC (colitis) can be used [7-9]. When multiple segments of the GI tract were involved, the condition was named accordingly, such as EoG + EoD, EoE + EoC, etc. Multiple-segment involvement is more common in children than adults [2]. Classification based on GI wall layer involvement includes the mucosal, muscular, and serosal types. EGIDs are mostly of the mucosal type.

• Example: EoG, muscular type

A 7-month-old infant was transferred with persistent projectile vomiting that started after switching from regular to soy formula. Endoscopy revealed severe edema in the gastric antrum leading to pyloric obstruction, and a biopsy confirmed eosinophilic infiltration. The patient's condition improved following intravenous methylprednisolone treatment, and the formula was changed to an extensively hydrolyzed formula. Follow-up endoscopy performed several months later revealed complete resolution [10].

This case report presents a rare muscular type of EoG involving the gastric antrum of an infant. Its findings suggest that symptoms such as projectile vomiting, infantile colic, and pyloric spasms in newborns and young infants may be related to milk allergies. Furthermore, infants aged >3 months with suspected hypertrophic pyloric stenosis might have an early muscular form of EGID necessitating a careful differential diagnosis.

3) Current incidence, prevalence, and demographic features of non-EoE EGIDs

EGID are often underdiagnosed because of various challenges including the nonspecific nature of symptoms that overlap with those of more common GI disorders, lack of awareness among general practitioners, and the need for specialized diagnostic tools such as endoscopic biopsy and targeted histopathological analysis, which may not be available in all healthcare settings.

The incidence of EGIDs, once considered rare, has significantly increased over the past few decades in Korea, potentially exceeding the prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in children [11]. Unlike IBD, which affects both children and adults, EGID is more commonly diagnosed in children, likely because of the higher prevalence of food allergies among them. Children with non-EoE EGIDs often have a higher incidence of allergic conditions (e.g., rhinitis, asthma, and atopy) than adults and the general pediatric population. As diagnoses increase rapidly in the pediatric population, the number of adults with non-EoE EGIDs is also increasing [1,12]. According to a recent nationwide Japanese survey, pediatric non-EoE EGIDs are more persistent and severe than adult EGIDs [13]. However, few studies have been conducted of EGIDs in Korean children. A national multicenter study of pediatric EGID based on the updated nomenclature is underway.

2. Pathogenesis/natural history

1) Mechanism of non-EoE EGIDs

EoE and non-EoE EGIDs are similar in pathogenicity as they are triggered by food antigens. The mechanisms of non-EoE EGIDs remain unclear; however, it is believed that there are differences in their pathogenesis across different GI segments. The immune responses involved in the pathogenesis of EGIDs are complex and include Th2 cell activation, eosinophil-activating inflammatory cytokine overexpression, the presence of excessive eosinophils in the GI tissue, and food antigen-specific IgE antibodies [14,15].

(1) Leaky gut

In cases of eosinophilic enteritis, a "leaky gut" mechanism has been used to explain the condition. Infants may become sensitized to food proteins following GI illnesses. Compromised integrity of the intestinal mucosa results in a leaky gut, which allows food antigen proteins to pass through the lamina propria. T cells respond to antigens that penetrate the gut barrier and enter the bloodstream, and the cytokines secreted by these T cells destroy the GI mucosal epithelial cells, leading to inflammation. This exacerbates leaky gut, creating a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation.

Eosinophil accumulation at sites of GI inflammation is achieved through adaptive and innate Th2 responses as well as subtypes of tissue eosinophils [16].

(2) Breastfeeding

The maternal microbiota during pregnancy plays a crucial role in fetal and infant immunity, influencing immune-mediated diseases such as autoimmunity and atopy. This process involves the translocation of maternal gut microbes and metabolites that create a lasting immune imprint after birth [17]. Breast milk is essential for shaping the infant gut microbiome, offering beneficial bacteria that reduce the risk of allergic diseases and have lasting effects even after solid foods are introduced, highlighting its importance in promoting a healthy microbiome [18]. Reduced breastfeeding rates and increased cesarean section rates have been associated with insufficient transmission of maternal gut microbiota to newborns, leading to dysbiosis, bacterial translocation, intestinal inflammation, and increased gut permeability in infants [19]. These factors are presumed to be related to the mechanisms underlying EGIDs [20,21]. Pregnant women and postpartum mothers planning to breastfeed should be careful about foods, especially herbal medicines, that may affect the fetus and newborn.

(3) EGIDs vs. non-IgE-mediated GI allergies

A 4-month-old infant presented with 7 episodes of bloody and mucus-filled stools per day over 3 weeks. The severity of the symptoms raised the suspicion of FPIES rather than allergic proctocolitis. Symptoms improved with treatment using an amino acid-based formula.

FPIES may histologically overlap with non-EoE EGIDs. The relationship between non-IgE-mediated food allergies and EGIDs in infants is unclear, and it can be difficult to determine whether they are independent, coexistent, or transitory.

2) Can food allergies cause non-EoE EGIDs?

Non-EoE EGIDs typically manifest as a general pattern of GI food allergies. Although initially categorized as non-IgE-mediated food allergies, they are currently recognized as having a mixed type of both IgE-mediated and non-IgE-mediated food allergies. However, the fundamental immune response in non-EoE EGIDs is non-IgE-mediated, so it is crucial not to conclusively attribute foods that test positive in IgE assays, such as MAST, as causative agents. Indeed, in some patients with non-EoE EGIDs, foods that test positive on IgE tests may exacerbate a patient's symptoms; however, this should be interpreted as a positive result owing to associated IgE-mediated allergies (e.g., rhinitis), atopy, or asthma.

3) Are non-EoE EGIDs chronic?

The course of non-EoE EGIDs varies significantly among patients. Some patients experience an initial episode and remain symptom-free without recurrence, whereas others may experience multiple relapses and periods of remission, with some progressing to chronic disease. Adolescents diagnosed during childhood who remain in remission can manage their condition to prevent relapse. However, if the diagnosis is not made until adulthood, the likelihood of the condition becoming chronic increases.

These dynamics underline the complexity of non-EoE EGIDs and emphasize the importance of early diagnosis and tailored management strategies to alleviate long-term effects and improve the quality of life of affected children.

3. Symptoms/biomarkers/endoscopy/imaging studies

EGIDs affect various parts of the GI tract. The eosinophil count and specific IgE antibody levels in blood tests are neither specific nor sensitive biomarkers. The past trend in IgG4 antibody tests, which has recently resurfaced, has no diagnostic value for EGIDs. Similarly, specific IgG antibody tests for foods are not helpful for diagnosing EGID. Although skin prick tests yield positive results in some patients, their utility as routine screening tests remains unclear. The overall appearance of the mucosa during endoscopy could be normal during stable phases, but mucosal edema and infiltration may occur during exacerbations.

1) Main symptoms and signs of non-EoE EGIDs

The primary symptoms of non-EoE EGIDs vary by affected GI segment location. The extent of involvement, depth of inflammation through the GI wall layers, and degree of eosinophilic inflammation determines the patient's clinical presentation (Table 2). Although rare, intussusception can occur; therefore, caution should be exercised. The symptoms are nonspecific; thus, a systematic diagnostic algorithm that considers other disease conditions should be employed before confirming EGIDs.

2) Does symptom severity in non-EoE EGIDs reflect eosinophilic inflammation severity?

There are currently no validated tools for assessing symptom severity, which makes it difficult to correlate symptoms with eosinophilic inflammation degree. However, patients with severe mucosal findings and eosinophil infiltration commonly experience a significant reduction in eosinophilic inflammation after treatment [1,10,22].

(1) Hematemesis as presenting symptom of EGID

A 6-month-old infant presented with a 2-month history of weekly episodes of hematemesis. Upon suspicion of EoG, the formula was changed to an extensively hydrolyzed hypoallergenic formula, which led to improvement.

Immediate GI hypersensitivity typically does not include hematemesis as a common symptom in early infancy. Therefore, it is important to assess neonates for other underlying conditions that may lead to hematemesis. In one case report, EoG was diagnosed as the cause of hematemesis in a 10-week-old infant [23].

(2) Hematemesis in a newborn with heavy eosinophil infiltration

A 2-day-old newborn presented to our hospital with life-threatening hematemesis. An endoscopic examination confirmed hemorrhagic gastritis, which was presumed to be an immediate GI hypersensitivity reaction to milk proteins. However, the total IgE level was normal and the UniCAP test results negative. Biopsy of the gastric antrum observed under ×400 magnification showed 38 eosinophils.

Infants tend to have higher eosinophil counts in the GI mucosa than older children [1]. Although more than 20 eosinophils per high-power field (HPF) at ×400 magnification strongly suggest EoG and EoD (duodenal bulb), universally agreed diagnostic criteria for eosinophil counts across various GI segments for non-EoE EGIDs remain undefined [9]. Additionally, the highest eosinophil counts in the GI tissue did not follow a normal distribution. Repeated biopsies can increase the diagnostic sensitivity.

(3) Hematemesis in neonates: EGID or not?

Twenty years ago, when newborns presented with hematemesis, it was challenging to consider formula allergies as the cause of GI bleeding in neonates. An endoscopic examination was performed to determine the cause of the hematemesis. During the procedure, 5 cc of cow's milk formula was sprayed into one part of the stomach using an endoscopic injection needle and immediately aspirated. Eosinophil infiltration was significantly increased in the postchallenge mucosal biopsies. Additionally, in another neonate, although the gastric mucosa returned to normal after fasting posthematemesis, mucosal erythema was observed upon re-exposure to the antigen.

Hematemesis in neonates or very early infants may be due to an IgE-mediated and/or non-IgE-mediated EGID caused by cow's milk protein. These cases demonstrated that not only could tissue eosinophils increase upon reexposure to the antigen, but immediate mucosal changes were also possible.

3) Is peripheral eosinophilia helpful in diagnosing or monitoring disease activity in non-EoE EGIDs?

Specific biomarkers for diagnosing and monitoring EGID activity are currently lacking. Although an increase in peripheral eosinophils and abnormal total IgE levels can occur in symptomatic children with non-EoE EGIDs, these are neither specific nor sensitive indicators of this condition and could be related to other conditions, such as active EoG or associated allergies [4]. Additionally, these markers do not reliably reflect improvements in tissue inflammation. However, in some patients in whom mucosal eosinophil infiltration consistently correlates with disease activity, peripheral eosinophilia may be an adjunct tool for assessing disease activity.

Peripheral eosinophilia is commonly observed in patients with eosinophilic enteritis; however, it is not a diagnostic biomarker for non-EoE EGIDs. Although peripheral eosinophilia may improve after EoN treatment, it cannot be relied upon as a measure of treatment success. Peripheral eosinophilia does not reflect disease activity; even in severe cases, peripheral eosinophil counts may be normal. Research from a children’s hospital in Korea emphasized the need to suspect EGID when nonspecific GI symptoms and peripheral eosinophilia are present. Most patients improved with dietary restrictions or steroid treatment; however, one-third experienced relapse or were steroid-resistant [24]. It has a relatively high recurrence rate and negative outcome, as the study was conducted in a hospital that specializes in treating critically ill children.

4) Is fecal calprotectin helpful for diagnosing or monitoring disease activity in non-EoE EGIDs?

The use of fecal calprotectin (FC) concentrations to diagnose or monitor the activity of non-EoE EGIDs is not recommended. FC measures intestinal inflammation through the presence of neutrophils in the stool, which does not directly reflect the eosinophilic inflammation typical of non-EoE EGIDs. FC levels increase in the presence of neutrophilic inflammation; thus, they increase in conditions such as bacterial enterocolitis or the active phase of IBD. In patients with FPIES, FC levels may increase during symptom exacerbation and normalize upon improving. For patients with EGID who present with abdominal pain without accompanying FPIES, FC is a nonspecific test.

However, according to a study in Korea, FC levels were significantly elevated in pediatric patients with EGID versus those with functional abdominal pain (FAP) [25]. The author also observed that FC levels surged during acute exacerbations in patients with EGID and remained normal when the patients were cautious about their diet and were symptom-free. This suggests that FC can also aid in differentiating EGIDs from IBD and might help identify trigger foods in some children.

5) Endoscopic findings and appropriate biopsy protocols for diagnosis

Patients with EoG or EoN often exhibit various nonspecific endoscopic findings. The most common finding in all EGIDs is a normal appearance; however, findings can include mucosal edema, erythema, nodules, erosions, and in severe cases, bleeding and deep ulcers. In patients with EoC, colonoscopic findings can include mucosal nodules, edema, and mucosal damage, although many patients present with visually normal colonic mucosa [4]. Capsule endoscopy allows for the detailed inspection of mucosal changes in the small intestine, in which erythema or redness is the most common finding, followed by villous atrophy, erosions, ulcers, and edema. The lack of awareness about EGID or severe lesions of EoN can sometimes lead to a misdiagnosis of Crohn disease [26].

For symptoms suggestive of EoG/EoD, endoscopic biopsies should include as many tissue samples as possible from various parts of the stomach and duodenum, including both normal and abnormal areas (8 gastric and 4 duodenal samples is recommended, although this may be practically challenging in children) [27]. If EoC is suspected, biopsies should be obtained from normal and abnormal mucosa in the terminal ileum and colon (at least 3 sites). Labeling biopsy specimens in separate containers can aid in interpreting eosinophil counts based on the biopsy site, using consensus threshold values for EGID diagnosis.

The diagnosis of EGIDs typically relies on endoscopic biopsy; however, eosinophilic infiltrations can be patchy, making it difficult to identify and biopsy highly eosinophilic dense tissues through visual inspection alone. Even if the mucosa appears normal, performing biopsies at multiple sites may improve diagnostic results. Histologically confirmed EGIDs may be far less prevalent than the actual number of affected individuals owing to factors such as nonperformance of endoscopy, grossly normal mucosa not biopsied, inaccessible small intestinal lesions, or healed mucosa obscuring diagnosis. Establishing a single standard value for peak eosinophil counts could lead to the over- or underdiagnosis of EGID; a cutoff value that is too high may hinder the confirmation of EGID. An improvement in clinical symptoms is correlated with a decrease in tissue eosinophilia and improvements in endoscopic and histological findings [28]. Based on the author's experience, biopsies taken during symptomatic exacerbations can enhance diagnostic accuracy.

High index of suspicion - eosinophil infiltration verification process: A 12-year-old child presented with severe abdominal pain lasting 2–3 hours daily that recurred weekly for 6 years and was intense enough to wake the child from sleep and provoke suicidal thoughts. Blood test results, including MAST and UniCAP, were normal. An upper endoscopy revealed normal gross histological findings.

To confirm the biopsy results, the author asked the attending pathologist to re-examine the slides, which revealed significant eosinophilic infiltration in the duodenum and led to a diagnosis of EGID. The patient's caregivers were advised to maintain a food diary during exacerbations, and melons and crabs were identified as trigger foods and excluded from the diet. Findings of follow-up endoscopy and biopsy performed 1 year later were normal, and all allergy-related medications were discontinued. The patient remained well without any special issues until 30 years of age.

The patient visited our hospital when EGIDs were rarely diagnosed in Korea. Initially, several organic diseases, including EGID, were suspected; however, because all test results were normal, a diagnosis of EGID could not be made without tissue reconfirmation. This case emphasizes the importance of communication between pathologists and physicians to ensure a proper diagnosis, particularly by quantifying peak eosinophil counts.

6) Are imaging studies helpful for evaluating children with non-EoE EGIDs?

Abdominal ultrasound, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging are not directly helpful for diagnosing non-EoE EGIDs, particularly mucosal EGIDs. However, multisite inflammation is more common in children with EGIDs than in adults. In some severe cases, especially those with muscular or serosal EGIDs, imaging can reveal wall thickening or obstruction. In such cases, small-bowel enterography (via CT or MR) can be beneficial, which is particularly useful in diagnosing Crohn disease.

7) Can other tests assist in the diagnosis or monitoring of disease activity in non-EoE EGIDs?

Routine blood tests may show abnormalities in some patients, but these findings are not specific to non-EoE EGIDs. These may have been secondary findings under other concurrent conditions. For instance, in cases of non-EoE EGIDs associated with protein-losing enteropathy, related blood tests and fecal alpha-1 antitrypsin measurements are necessary monitors during diagnosis and treatment.

(1) EoN, serosal type

A 6-month-old infant presented with generalized edema. The infant had decreased albumin and IgG levels and an elevated fecal alpha-1 antitrypsin, leading to a diagnosis of protein-losing enteropathy, which improved after EGID treatment.

Several infants with protein-losing enteropathy and iron-deficiency anemia have been reported in Korea [29]. Serum eosinophil cationic protein levels and peripheral eosinophil counts, when used together with appropriate threshold values, can serve as noninvasive biomarkers to differentiate between EGID and FAP in pediatric patients presenting with GI symptoms [30]. An ascitic fluid analysis showed prominent eosinophils, suggesting serosal non-EoE EGIDs.

(2) EGID, mucosal + serosal type

A 9-year-old child developed intractable vomiting and ascites following an influenza virus infection. Abdominal CT revealed significant ascites and edematous wall thickening of the small-bowel loops. An endoscopic mucosal biopsy and laparoscopic small-bowel wall biopsy confirmed combined mucosal + serosal type EGID [31].

These cases highlight the importance of a comprehensive evaluation of suspected non-EoE EGIDs, including both invasive and noninvasive diagnostic approaches. Although not always directly useful for mucosal types, imaging studies can be crucial for assessing severe forms and guiding further diagnostic steps such as biopsy. An effective diagnosis often requires a combination of clinical evaluation, biopsy, and appropriate imaging and laboratory tests to confirm the disease presence and extent and monitor the treatment response.

4. Histology

1) Maximum eosinophil density in healthy pediatric GI mucosa and current diagnostic thresholds for non-EoE EGIDs

The diagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs is not solely dependent on histological findings, as the patient's condition must correlate with the symptoms and signs. From the pathologist's perspective, non-EoE EGID is a diagnosis of exclusion. The diagnosis is supported by mucosal biopsies that demonstrate increased eosinophil counts within the inflamed tissues.

2) Peak GI mucosal eosinophil counts

Studies investigating eosinophilic infiltration into the GI mucosa of children without organic GI diseases are summarized in Fig. 1. Notably, a 0.27 mm² HPF has been used to standardize magnifications across different microscopes (http://links.lww.com/MPG/D224). It is important to use eosinophil density (eos/mm²) rather than eos/HPF because of varying HPF sizes across microscopes. The conversion formula used was as follows: eos/mm² = eos/HPF × 1/area of the microscope HPF in mm².

Consensus threshold peak eosinophil counts (per 0.27 mm² high-power field) in children for the diagnosis of non-EoE EGID. EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; EGID, eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorder; A, ascending; D, descending; S, sigmoid; T, transverse.

Recent consensus guidelines have opted for a higher cutoff number for eosinophil density (Fig. 1) to diagnose non-EoE EGIDs to prevent overdiagnosis, especially among patients with atopic conditions in which increased GI mucosal eosinophil counts may be observed. However, this approach may lead to an underdiagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs. Therefore, both eosinophil counts and pathological tissue findings and clinical diagnostic criteria should be considered to ensure a comprehensive diagnosis.

3) Additional histological features helpful for characterizing affected GI mucosa

Pathological features that are generally not associated with non-EoE EGIDs cannot conclusively rule it out. These features include acute neutrophilic inflammation, glandulitis, cryptitis, and even granuloma formation, which are characteristic of IBD but can also be seen in biopsies from patients with non-EoE EGID-related ulcers/erosions or parasitic infections.

The presence of chronic signs such as atrophy and fibrosis of the stomach and duodenum, blunting of the villi, and crypt distortion of the small intestine are useful histological markers for diagnosing non-EoE EGID in cases of eosinophilic infiltration in the GI mucosa, especially when endoscopic findings appear normal [4]. Therefore, it is important to assess and document the features of acute and chronic mucosal inflammation.

5. Differential diagnosis

1) Comprehensive evaluation for other associated clinical conditions

A thorough medical history should be obtained to identify any exacerbating factors such as diet and fever. The diagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs should only be made after excluding secondary causes such as inflammation or systemic diseases. These include IBD (Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis); hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES); food allergies and drug hypersensitivities; exposure to toxins or foods; infections; autoimmune diseases and vasculitis; adrenal insufficiency; connective tissue diseases; leukemia and malignant tumors; graft-versus-host disease; immune dysregulation; and hyper-IgE syndrome. Fortunately, systemic diseases other than IBD are relatively rare in Korean children and can be ruled out with appropriate evaluation. Family histories should be reviewed to check for the presence of atopy, autoimmune diseases, and IBD.

Currently, intestinal parasitic infections, with the exception of Enterobius vermicularis, are rare in Koreans. Fecal polymerase chain reaction testing can assist in ruling out parasitic and bacterial GI infections, and Helicobacter pylori can be screened using the urea breath test. The prevalence of H. pylori infection among Korean children continues to decline [32].

(1) Cyclic vomiting syndrome triggered in EGID patients

A 12-year-old girl visited a local clinic repeatedly because of intractable vomiting that had persisted for several years. Cyclic vomiting syndrome prophylaxis was administered; however, repeated relapses occurred. After the confirmation of eosinophilic infiltration of the gastric mucosa through gastroscopy, the EGID was managed concurrently and improvement was achieved.

The author also encountered a case of EoD in a boy with idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis but was unable to confirm a causal relationship with pancreatitis or eosinophilic pancreatitis [33].

(2) Concurrent gastric or duodenal ulcers in patients with EGID

A 15-year-old boy presented with a 4-year history of abdominal pain. Deep duodenal ulcers were discovered during endoscopy, and H. pylori was detected, leading to eradication treatment. Despite successful eradication, duodenal ulcers frequently recurred, and biopsies around the ulcers showed significant eosinophil infiltration, which was worsened by specific foods.

Although eosinophil infiltration in the duodenum can increase due to the presence of ulcers, the possibility of EGID should be considered. A similar case was reported in Japan [34]. This case highlights the need to consider EGID in the differential diagnosis, especially when typical treatments do not effectively resolve symptoms. A recent study by Yang et al. in Korean children with recurrent peptic ulcer disease reported that EGID should be suspected in the absence of H. pylori [35].

2) Diagnostic criteria for pediatric non-EoE EGIDs

The initial assessment of patients presenting with mucosal eosinophilia should carefully consider the reported symptoms, medical history, physical examination findings, laboratory findings, and relevant GI sites. This comprehensive approach is crucial for differentiating between various conditions such as allergic diseases, parasitic infections, drug reactions (especially with immunosuppressants), IBD, and malignancies [36]. The necessity for GI endoscopy should be determined based on the patient's symptoms and laboratory/imaging study findings.

The diagnosis of non-EoE EGIDs in children should include the following: (a) symptoms and signs of GI dysfunction vary widely. These include but are not limited to abdominal pain, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhea, constipation, hematemesis, bloody stool, abdominal distension, ascites, anorexia, weight loss, and protein loss. (b) High-density eosinophilic infiltration of the mucosa. (c) No other diseases associated with eosinophilic inflammation of the GI mucosa.

3) Coexisting IgE-mediated and/or non-IgE-mediated food allergy with non-EoE EGIDs

Reaching a global consensus on non-EoE EGIDs remains challenging owing to variations in patient selection across studies, which may include individuals with food intolerance or IgE-/non-IgE-mediated allergies and cases in which EGIDs were not definitively diagnosed. Furthermore, misdiagnoses due to erroneous methodologies have been reported, making it difficult for experts to develop diagnostic and treatment guidelines for EGIDs. Special attention is needed for the differential diagnosis, especially in cases in which EGID coexists with IgE-/non-IgE-mediated GI immune reactions.

(1) EoG vs. IgE-mediated hypersensitivity

One-day-old newborns experienced massive gastric hemorrhage with significant mucosal swelling, erythema, and telangiectasia immediately after the first formula feeding.

Although a biopsy could not be performed because of the severe bleeding tendency due to prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time, it was assumed that gastric bleeding due to milk allergy did not stop due to the underlying hemophilia [37]. The gastric bleeding in this newborn suggested immediate GI hypersensitivity. Although eosinophilic infiltration was not confirmed, it is uncertain whether EoG coexisted or whether upper-GI bleeding could accompany an IgE-mediated food allergy.

(2) Coexisting non-IgE-mediated GI allergy

A 2-week-old newborn presented with ongoing symptoms of hematochezia, melena, and diarrhea mixed with mucus starting 4 days after birth. The infants received mixed feeding. The symptoms were consistent with those of FPIES; however, the presence of melena suggested the involvement of conditions such as EoG or EoD. Given the symptom severity and range, comorbid EoG, EoN, and FPIES was suspected. The infant's formula was switched to an amino acid-based formula, which led to symptom improvement.

One case of neonatal FPIES reportedly featured severe eosinophilic infiltration of the sigmoid colon, suggesting that it may have been accompanied by EGID [38]. In Japan, 2 newborns were reported to have bloody stools before their first feeding, and sigmoidoscopy revealed findings similar to those of allergic proctocolitis, which was accompanied by eosinophilia and positive specific IgE to milk (class 3) in the blood [39].

Children with non-EoE EGIDs may present with symptoms typical of the oral allergy syndrome, urticaria, and other IgE-mediated GI allergies, often accompanied by atopy, asthma, and rhinitis. The occurrence of non-IgE-mediated GI allergies, such as FPIES, FPIE, and allergic proctocolitis, is not rare in infancy. The symptoms of FPIES or FPIE may persist during infancy. A history of infantile colic and projectile vomiting is common. It can be assumed that children with cow's milk allergies from early infancy develop allergic march as they grow up, implicating food allergies as a significant contributor to non-EoE EGIDs.

4) Differential diagnosis: FGIDs versus non-EoE EGIDs

(1) Eosinophil infiltration in children with FGID

In some patients with FGIDs, an increase in eosinophils is observed in the duodenum [40]. Recent studies have explored a new diagnostic category known as eosinophilic functional dyspepsia that overlaps with the symptoms and diagnosis of functional dyspepsia [41]. Thus, there is a need to redefine the coexistence and distinction between EGIDs and severe symptoms of FGIDs. Lee et al. [42] suggested that GI eosinophilia may be associated with FAP disorder in children.

(2) Coexisting conditions

FAP disorder and IBD are associated with eosinophilic infiltration of the GI tract. Patients with IBD may exhibit symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), while those with EGIDs may experience FAP or IBS. It can be challenging to determine whether severe symptoms in patients with FGIDs are indicative of early or coexistent organic diseases.

5) Differential diagnosis: IBD vs. non-EoE EGIDs

Criteria and considerations: The diagnostic criteria for non-EoE EGIDs include the absence of other GI diseases, indicating that they cannot coexist with IBD. However, patients with IBD may also have various food intolerances, and mucosal eosinophil infiltration can be significantly higher than that in children with FGIDs and healthy controls. In the early stages of IBD, it may be mistakenly identified as non-EoE EGIDs; even after diagnosis, it may appear to coexist with EGID. Conversely, severe cases of non-EoE EGIDs can mimic early IBD in terms of symptoms and endoscopic findings, necessitating a careful differential diagnosis.

(1) Diseases or disorders that mimic IBD

① An 11-year-old boy presented with a 5-year history of RAP and chronic diarrhea, and he was noted to be short for his age and frequently have oral ulcers. Symptoms, including diarrhea and vomiting, worsened with daily intake.

② A 14-year-old boy experienced RAP and chronic diarrhea and was treated for 3 months in a private clinic but presented with a 12-kg weight loss.

③ A 15-year-old boy presented with chronic diarrhea and a 5-kg weight loss over several months. His IgE level was 437 IU/mL, with positive MAST results for crab and shrimp. The food diary linked these symptoms to crab consumption.

④ A 16-year-old boy presented with RAP and a 15-kg weight loss over 7 months. She had a history of surgery for a fistula secondary to hematochezia.

All 4 patients were ultimately diagnosed with conditions other than IBD, including IBS, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, food intolerance, and non-EoE EGIDs. All patients showed improvement after the elimination of aggravating factors and implementation of dietary adjustments. Due to the increasing prevalence of IBD and EGID, it is essential to maintain a high index of suspicion for non-EoE EGID and IBD in children with chronic diarrhea and recent weight loss.

(2) Early Crohn disease

A 20-month-old infant presented with a 3-month history of hematochezia. Six months later, the patient developed a limp, and noncaseating granulomas were noted on colonoscopy. Initially considered non-EoE EGID, a subsequent colonoscopy revealed multiple severe ulcers, confirming Crohn disease.

(3) Early ulcerative colitis

A 2.5-year-old child presented with chronic abdominal pain, diarrhea, and 4 episodes of hematochezia per day. Several aggravating foods were identified. His perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody level was 235 IU/ mL, and colonoscopy revealed patchy infiltrates with eosinophil counts of 60–100/HPF. The patient’s condition improved with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy, indicating that the ulcerative colitis was exacerbated by food-triggered lesions, although severe non-EoE EGID was also considered.

6) Hypereosinophilic syndrome

A 3-year-old presented with high fever; a complete blood count showed a white blood cell count of 28,000/μL with 30% eosinophils. The child exhibited growth retardation and anemia (hemoglobin, 7.1 g/dL). High levels of IgE (2802 IU/mL) and FC (946 μg/mg) were noted. A bone marrow biopsy revealed 10% eosinophilic infiltration. Treatment with prednisolone and a diet of extensively hydrolyzed formula and low-protein rice normalized the eosinophil counts and IgE, ESR, CRP, and FC levels, and his growth resumed.

HES is characterized by severe eosinophilia (>1,500/μL) in the blood leading to complications in organs such as the heart, lungs, and nervous system distinct from typical non-EoE EGIDs. EGIDs can cause systemic symptoms and organ dysfunction owing to eosinophilic infiltration beyond the GI tract. EGIDs and HES share common features. Patients with multiorgan HES may present with isolated GI symptoms before symptoms involving other organs appear [43]. HES can lead to the secondary development of EGIDs, demonstrating a complex interplay between systemic and organ-specific eosinophilic disorders.

6. Treatment

Dietary management: Removing suspected proteins from the diet typically resolves a patient's symptoms within a few days to weeks, but most infants eventually overcome specific protein allergies after prolonged dietary restriction. However, the continuous consumption of foods that cause mild allergic reactions, even during periods of improvement, can delay a patient's recovery.

IgE tests may not identify the cause, and a positive result does not necessarily indicate that food should be excluded from the diet. If no issues are experienced after consumption, a food was not considered a trigger for EGID exacerbation. Conversely, foods testing negative for IgE cannot be considered safe. It is crucial to maintain a food diary to identify safe foods and cautiously introduce and gradually increase potential triggers.

Natural course and treatment considerations: The natural course of non-EoE EGIDs is uncertain, and spontaneous remission without treatment is rare. Randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials are rare. Patients may experience periodic flare-ups over months or years that potentially lead to severe malnutrition. Affected patients often require long-term maintenance therapy; thus, decisions regarding long-term treatment should involve discussions with patients and their parents.

1) Treatment goals for non-EoE EGIDs

Treatment goals include resolving symptoms, improving endoscopic and histological abnormalities, promoting catch-up growth and development, and preventing disease complications. The timing of endoscopic and histological re-evaluation must be determined on an individual basis.

2) Effectiveness of systemic oral steroids in inducing remission in non-EoE EGIDs

In some case series, oral steroids effectively induced clinical and histological remission in patients with non-EoE EGIDs. However, there are no specific data on the selection criteria for patients who should be treated with oral steroids, optimal dosages, or treatment duration for non-EoE EGIDs. The use of oral steroids should be considered on an individual basis, and the benefits and risks should be thoroughly discussed with the patients and their parents. The initial treatment of severe EGID typically involves the use of an appropriate dose of prednisolone that is gradually tapered over 1–3 months [44]. For instance, a regimen might include 0.5–1 mg/kg (up to 40 mg) for 2 weeks, followed by a reduction over 2–8 weeks if improvement is observed [45].

3) Effectiveness of dietary elimination therapy in non-EoE EGIDs

Dietary elimination, the primary treatment approach, involves the removal of causative proteins from the diet for a sufficient period. This approach can induce clinical improvement or complete remission in children with non-EoE EGIDs. However, data on histological responses to dietary elimination are limited.

Unreliable food allergy tests: While dietary elimination can lead to clinical improvements, there is no solid evidence supporting the use of food allergy testing as a guideline for dietary restriction practices, and its use is not recommended. Care should be taken to distinguish between IgE-mediated food allergies, which can cause symptoms such as urticaria, and EGIDs triggered by specific foods.

Common allergens and empirical elimination diets: There insufficient data on which specific foods can be eliminated; however, avoiding common allergens, such as milk, can be effective in some children. Therefore, an empirical elimination diet should be considered for patients with non-EoE EGIDs. For children with severe abdominal pain, asking parents to record the foods consumed before symptom onset can help identify triggers. Dietary management options include an elemental diet, a six-food elimination diet, or dietary restrictions on identified triggers [22]. A comparison of dietary management between a histologically proven EGID group and a clinically suspected EGID group showed clinical improvement after restricting suspected aggravating foods in both groups [1].

Both endoscopic and histological findings can be improved by diet. For example, a 9-year-old child presented with a hemoglobin level of 8.5 g/dL and albumin level of 2.8 g/dL. An upper endoscopic examination revealed linearly arranged pseudopolyps in the antrum. A biopsy revealed eosinophilic infiltration of 50–60/HPF, leading to a diagnosis of EoG. The initiation of exclusive enteral nutrition led to a significant reduction in the size of pseudopolyps and eosinophil infiltration [22].

4) Role of gastric acid suppressants, drugs for mast cell activation-mediated disorders, immunomodulators, and biologic agents in managing EoG/EoD

There is insufficient evidence (for or against) supporting the use of proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2-receptor antagonists for the treatment of EoG/EoD in children. However, proton pump inhibitors may be considered for the treatment of ulcers in children with EoG/EoD. There are insufficient data to recommend or oppose the use of antihistamines, leukotriene inhibitors, and mast cell stabilizers as standalone treatments for non-EoE EGIDs. Ketotifen, which acts as both an H1 antihistamine and mast cell stabilizer, can be used prophylactically in cases of food allergies [44].

Immunomodulators such as azathioprine may serve as alternatives for reducing steroid use; however, there are insufficient data to recommend their use specifically for treating non-EoE EGIDs. There are also insufficient data to recommend or oppose the use of biological agents for the treatment of pediatric non-EoE EGIDs.

5) Role of endoscopic procedures or surgery in non-EoE EGID management

Endoscopic dilatation may be considered selectively in cases with objective signs of obstruction despite medical and dietary treatments. Surgical intervention may be useful in patients with non-EoE EGIDs and uncontrollable intractable ulcers, intestinal perforation, or obstruction.

6) Need for combination therapy in non-EoE EGID treatment

Combination therapy has shown various effects in some patients with non-EoE EGIDs, but there are insufficient data to definitively recommend or oppose its use. However, combination therapy may aid the treatment of accompanying allergic diseases.

7) Recommended approaches to initiating treatment of non-EoE EGIDs

Due to the lack of randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of treatment options, an effective initial approach for treating most non-EoE EGIDs patients involves administering and appropriately tapering systemic steroids. The initial treatment for children with non-EoE EGIDs should be personalized based on their symptoms and other coexisting conditions as well as their impact on growth and development. The involvement of patients and their guardians in decision-making is also advisable. The use of objective tools to monitor symptoms and histological changes can help clinicians draw meaningful conclusions regarding treatment efficacy.

8) Proposed approaches to maintaining remission in non- EoE EGID cases

No study to date has investigated the role of maintenance therapy in patients with non-EoE EGIDs owing to the uncertain natural course of the disease. Discussions with patients and their guardians should include the benefits and risks of long-term treatment as well as its impact on quality of life.

The lack of a standardized approach to identifying food triggers in EGIDs means that elimination and rechallenge tests remain standard criteria but can be potentially risky and ethically sensitive. After clinical and/or histological goals are achieved, food rechallenge tests may be gradually initiated by guardians or adolescent patients. However, frequent trials before oral tolerance is achieved and subsequent failures leading to exacerbations can delay the onset of tolerance. Oral immunotherapy for food allergies can induce GI symptoms in many patients or trigger EGIDs in a minority of patients, thus necessitating caution [46].

Diet-related symptom diaries can help patients and their guardians identify potential food triggers and assess the effectiveness of dietary exclusion. Regular follow-ups can ensure the prompt adjustment of treatment plans and prevention of complications, thereby improving long-term outcomes.

Enhancing patients and caregivers’ understanding of EGID through educational programs and resources is crucial. Educating families about the patient's symptoms and management strategies as well as the importance of adherence to treatment plans can empower them and improve disease outcomes. Initiatives should focus on building supportive communities around patients to facilitate shared experiences and strategies for managing EGID.

Conclusions

EGID is no longer considered rare among children and adolescents in Korea, and its incidence is rapidly increasing. Owing to various diagnostic limitations, EGID is often underdiagnosed. A high index of suspicion is necessary to facilitate early diagnosis, which is critical for achieving optimal outcomes. The diagnosis should be based on clinical symptoms and histological evidence of eosinophilic inflammation after differentiation from other inflammatory or systemic diseases.

Early recognition and multidisciplinary approaches are crucial for the management of severe EGID cases. Tests such as FC and tissue biopsies can be especially helpful in acute and severe cases. It is essential to maintain a food diary to identify triggered foods and eliminate them in the long term. Appropriate treatment and management can significantly improve the quality of life and long-term prognosis of pediatric patients with EGID.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-forprofit sectors.