Anxiety disorders presenting as gastrointestinal symptoms in children – a scoping review

Article information

Abstract

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGID) and their association with anxiety disorders in children significantly impact a child’s functioning and treatment response. This study aimed to scope the evidence of anxiety disorders manifesting as FGID in children up to 16 years old. A comprehensive search strategy was conducted on Embase (1974-2024), MEDLINE (via EBSCOHost 1946-2024), and APA PsycINFO (via EBSCOHost 1967-2024). Articles were retrieved, screened, and assessed for bias using the GRADE system. Our initial search yielded 1984 articles. After screening titles and abstracts, 53 articles remained. Full-text screening further narrowed this to 4 eligible studies. The first study found that anxiety indirectly influenced abdominal pain severity in children with irritable bowel syndrome. The second study reported an association between anxiety and abdominal pain but found that anxiety might not predict abdominal pain in later childhood. The third study suggested FGID could be a risk factor for anxiety, with higher anxiety rates in children with FGID compared to those without. The fourth study found no significant difference in pain intensity between children with functional abdominal pain disorders (FAPD) alone and those with FAPD and anxiety. The reviewed studies indicate a relationship between anxiety and FGID but lack clarity on directionality or causation. The limited number of studies calls for more research, including case-control studies with large sample sizes and longitudinal cohort studies to investigate the incidence and causation.

Key message

A positive bidirectional relationship between gastrointestinal disorders and anxiety, but with no clear aetiology, was identified. Factors such as somatisation and pain catastrophising resulted in poorer pain-related outcomes in children. Further studies are required to understand this relationship in order to have targeted treatments and ensure better long term outcomes.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Mental disorders are a leading cause of disability, with approximately 10%–20% of children and adolescents affected globally [1]. A national survey conducted in 2022 reported that 18% of children aged 7–16 years in the United Kingdom had a mental disorder [2].

Academic performance can be significantly impacted by anxiety, with children less likely to engage in school, have poorer academic performance, or leave schooling earlier compared to their peers [3]. It can also harm relationships with their peers [1]. Major global disasters, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, have further isolated children due to school closures, quarantine orders, increased family stress, and decreased peer interactions [4]. In addition, children with anxiety disorders are at a greater risk of a range of future mental disorders, including eating disorders [3]. Early recognition of anxiety disorders is essential for improving long-term health outcomes in the pediatric population.

The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision defines anxiety and fear-related characteristics “by excessive fear and anxiety-related behavioural disturbances, with symptoms that are severe enough to result in significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.” [5] Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) is “manifested by either general apprehension or excessive worry focused on multiple everyday events, most often concerning family, health, finances, and school or work, together with additional symptoms such as muscular tension or motor restlessness, sympathetic autonomic overactivity, subjective experience of nervousness, difficulty maintaining concentration, irritability, or sleep disturbance.” [5]

In 1958, Apley and Naish first defined children with medically unexplained abdominal pain as being "timid, nervous, anxious, or overconscientious; the type of children in whom emotional disturbance would be expected to develop." [6] The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and the brain are interconnected via the gut-brain axis, playing a role in appetite, satiety, and enteroendocrine signalling [7]. The pathogenesis of functional GIT disorders (FGID) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are not yet clearly understood. However, the role of the gut-brain axis has been at the forefront due to the association of high prevalence of depression and anxiety alongside these FGIDs [7]. Particularly in pediatric settings, youths with GIT symptoms, such as nausea, constipation, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, urge incontinence, satiety, and bloating, are more likely to develop anxiety disorders than those without GIT symptoms [8].

It may be difficult to assess whether anxiety manifests as a result of GIT issues or if anxiety causes GIT disturbances. For instance, children with constipation may be anxious and fearful of a painful bowel movement and could avoid further bowel movements, thus exacerbating their symptoms of pain associated with constipation [6]. There has not been enough information to understand the complexity of possible bidirectionality of the gut-anxiety relationship. Unfortunately, epidemiological studies have been hampered due to the lack of appropriate diagnostic criteria for anxiety disorders in GIT conditions [9]. Furthermore, the complexities involved with the relationship between anxiety and FGIDs in the pediatric population and the paucity of clinical guidelines, makes it clinically difficult in regards to the management.

Therefore, this scoping review aims to review the evidence of anxiety disorders manifesting as GIT symptoms in children, particularly to look at the gaps in research, the prevalence, and clinical features.

Methods

1. Search strategy

Comprehensive search strategies were conducted on several databases on January 29 2024:

• Embase (1974–2024)

• MEDLINE (via EBSCOHost 1946–2024)

• APA PsycINFO (via EBSCOHost 1967–2024) The specific search strategies are displayed in Supplementary material 1.

2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants of both sexes under the age of 16 with either a clinical diagnosis of a functional gut disorder or anxiety were included. Clinical manifestations of anxiety or gastrointestinal symptoms needed to be included in the investigation. Children with diagnoses of conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), coeliac disease, or other malignancies were excluded to minimise confounding factors. The use of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), hypnotherapy, and antidepressants in the treatment of GIT manifestations of anxiety were also excluded. Only papers from the last 10 years were included.

Restrictions to the study design included case studies, pilot studies, or methodological studies. All studies that were not written in English or not peer-reviewed were excluded.

3. Data extraction

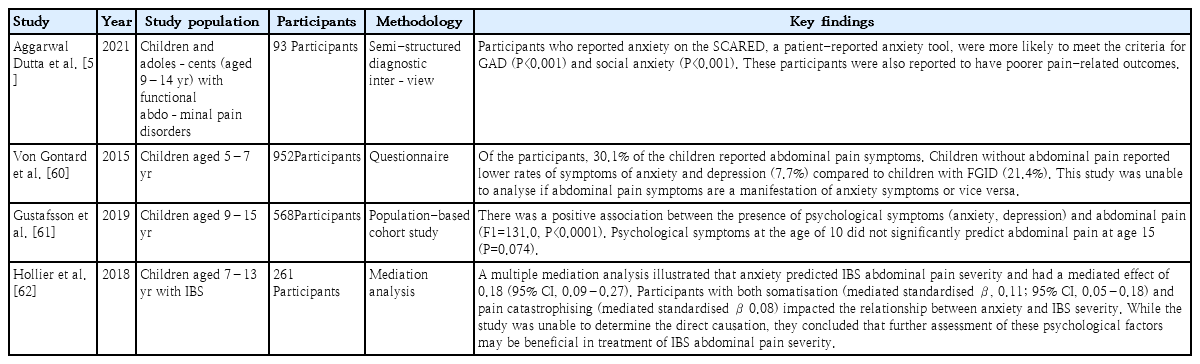

The screening process is summarised by the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses), which is shown in Fig. 1. The final selected papers are summarised in Table 1. The final data extrapolation includes key information such as author, publication date, study design, study population, and key findings.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses) flowchart depicting the inclusion and exclusion process to yield the final studies for data extraction.

4. Quality assessment

The 5 GRADE considerations approach was used to assess the overall quality of evidence. The factors considered include risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias.

Results

1. Search results

The search yielded 1984 citations, and 53 were selected for full-text assessment. Of the selected, 49 were excluded for the following reasons: wrong outcome (studies without a focus or subfocus of anxiety and FGIDs) [10-24], wrong patient population (patients over the age of 16 years or with diagnoses of IBD, coeliac disease, or malignancy) [25-44], wrong study design (case studies, pilot studies, or methodological studies) [45-49], wrong intervention (use of psychological therapies) [50-56] or not written in English [57,58]. Finally, 4 papers were included for final data extraction [59-62].

2. Role of anxiety in influencing abdominal pain severity

Two studies found the presence of anxiety and the influence they had on the severity of abdominal pain.

One study that looked at children with IBS found that somatisation and anxiety were significant mediators in the relationship between anxiety and IBS abdominal pain severity [62]. Furthermore, anxiety had a significant role in predicting IBS abdominal pain severity. The authors suggest that the effects of anxiety on IBS outcomes, such as pain, may be indirect through various mediating factors, such as somatisation [62]. The authors also suggested that psychological treatments such as CBT may be beneficial in reducing symptomology in children with IBS.

The second study found that children with functional abdominal pain disorders (FAPD) who reported anxiety on their proposed SCARED (Screen for Anxiety and Related Disorders) screening tool were more likely to meet the criteria of GAD (P<0.001) and social anxiety (P<0.001) [59]. These children were also likely to report significantly higher pain-related disability (P=0.007) compared to children with only FAPD [59]. However, when the study accounted for age and sex, there was no statistical difference between the groups for levels of pain catastrophising (P=0.065) and pain intensity (P=0.367) [59].

3. The relationship between anxiety and GIT conditions

Two studies found a positive association between the presence of anxiety and GIT symptoms, such as abdominal pain.

One study found a positive association between psychological symptoms, including anxiety and nervousness, and abdominal pain [61]. While the study showed a positive association between psychological symptoms and abdominal pain, the authors were unable to predict if psychological symptoms would predict the presence of abdominal pain later on in adolescence [61].

The second study found that FAPD may be a risk factor for internalising disorders, such as anxiety [60]. Furthermore, this risk increases if the child fulfils the Rome-III criteria and may cause greater abdominal pain severity [60]. However, similar to the other studies, the authors were unable to determine if abdominal pain symptoms were a direct consequence of anxiety [60].

The findings from these 4 studies have been summaried in Fig. 2 and Table 1.

Discussion

This scoping review identified a bidirectional relationship between anxiety and GIT disorders. However, it did not confirm whether there is a direct causal relationship or if the 2 share a common aetiology. The study was limited to selecting studies that primarily investigated GIT symptoms causing anxiety, with only 1 study reporting anxiety as the primary condition [61]. This limitation may be due to the fact that while anxiety and depression are common in the pediatric population, they often go undiagnosed and untreated [63]. As a result, their potential role in exacerbating GIT disorders may be underexplored.

Furthermore, abdominal pain can be a vague symptom of anxiety and may not always represent a manifestation of FAPD. Clinically, this is particularly challenging, as children often struggle to articulate or localise their abdominal pain, making it difficult to determine whether it stems from anxiety or GIT disorders.

Many of the current screening tools for FGID do not distinguish between subclinical or clinical anxiety, and are often based on the child or their family’s perception of anxiety. When children present with abdominal pain or other related symptoms, distress and worry would be present. However, whether these should be considered pathological or diagnosed as anxiety may not be beneficial when determining the best intervention for these patients. Furthermore, there are no validated measures of gastrointestinal-specific anxiety or gastrointestinal avoidance for children with FAPDs [60]. These patients, who avoid situations that may stimulate their GIT symptoms, may have a transient benefit in improving their overall symptoms, but are not exposed enough for them to develop appropriate coping strategies. Therefore, therapies such as exposure-based CBT may be beneficial to these patients if they were able to be identified early enough [60].

In addition, many of these studies simplify anxiety under general psychological conditions, which may include sleep disturbances and depression. It may be difficult to isolate such psychological conditions in these studies, as they all may be related and influenced by the other. For instance, if a child is receiving significantly less sleep due to their GIT symptoms, they are more likely to be at a heightened state of emotional distress, and more susceptible to being anxious [64].

Previous research investigating the pathophysiology of conditions such as IBS has identified visceral hypersensitivity— an increased sensitivity to stimuli in the GIT— as a common feature [36]. However, the origins of this hypersensitivity remain unclear. It is uncertain whether it is mediated by the local gastrointestinal nervous system or by central modulators from the brain [36]. Pain receptors in the abdomen respond to mechanical and chemical stimuli [63], but pain perception is a complex process involving visceral sensitivity and psychological factors [65]. Studies have noted that psychosocial factors, such as anxiety and significant life events—including sexual, emotional, or physical abuse—may influence the manifestation of IBS [66].

It may also be beneficial to have population studies that look at this interaction between the brain and the GIT from childhood to adulthood [64]. One Swedish prospective longitudinal birth cohort study (n=3,391) found that psychological distress at 16 years of age was associated with new onset IBS at 24 years (odds ration [OR], 1.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–2.3) [64]. In addition, having any abdominal pain-related disorder at 16 years was associated with new onset psychological distress at 24 years (OR, 1.7; 95% CI, 1.2–2.5) [64].

If conditions such as IBS and FAPD are to be understood through a biopsychosocial framework (Fig. 3), a comprehensive and targeted approach may be necessary to provide holistic treatment for affected children. A multipronged strategy that addresses these disorders' physical and psychological aspects could yield more effective therapeutic outcomes.

Biopsychosocial framework which illustrates the 3 domains (biological, psychological, and social) and how they all interact to influence health outcomes.

Additionally, due to the limited number of studies that met the inclusion criteria, it may be necessary to explore further the roles of psychotherapy and psychopharmacology in treating GIT conditions. Such an investigation could indirectly help clarify the relationship between anxiety and GIT symptoms.

Within pediatric emergency departments, 45% of patients meet the criteria for a diagnosis of a mental disorder [65]. Given the prevalence of mental disorders in this population, more refined diagnostic tools are needed to improve long-term outcomes. Studies examining the relationship between chronic GIT disorders and anxiety have shown that early intervention in mental disorders improves adherence to therapy and leads to better clinical outcomes [64]. Some studies also found that participants with abdominal pain were more likely to experience health anxiety [43], suggesting that recurrent abdominal pain may be a somatic manifestation of emotional distress [34].

Animal models further support the idea that early-life adversity can increase the risk of both GIT and mental disorders [14]. These models suggest that, like brain plasticity, the pediatric gut microbiome is highly sensitive to environmental factors that can influence its maturation [14]. This raises the possibility that early interventions to mitigate psychological stress could positively impact the gut microbiome and overall GIT health.

Research implications

This review has identified the need to develop more objective screening or diagnostic tools for anxiety and GIT conditions for early intervention. More rigorous, randomised trials with larger sample sizes may be necessary. To identify the causative effect, longitudinal studies which look at separate cohorts with only anxiety disorders and only GIT symptoms with long-term follow-up will be required.

Conclusions

Numerous studies have highlighted a relationship between anxiety FGIDs, yet there remains a significant lack of clarity on the directionality and underlying mechanisms of this association. While it is well-established that individuals with FGIDs often report higher levels of anxiety, it remains unclear whether anxiety acts as a precursor to the development of these disorders or emerges as a consequence of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. This ambiguity stems from a paucity of rigorous research focused on determining causality, as many existing studies are cross-sectional, limiting their ability to establish temporal relationships.

To gain a clearer understanding of the link between anxiety and FGIDs, further research is urgently needed. In particular, large-scale case-control studies could help identify distinguishing factors between affected and non-affected populations, while longitudinal cohort studies would be instrumental in tracing the development of FGIDs in individuals over time. Such studies would provide valuable insights into whether anxiety precedes the onset of FGIDs or if these disorders independently trigger heightened anxiety. By investigating the incidence and causation, future research could inform more effective treatment approaches that simultaneously address psychological and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material 1 is available at https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2024.01732.

Search strategies

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study can be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: PV, AK; Data curation: AK; Formal analysis: AK; Methodology: PV, AK; Project administration: PV, AK; Visualization: PV, AK; Writing - original draft: AK; Writing - review & editing: PV, AK