Comparison and review of international guidelines for treating asthma in children

Article information

Abstract

Asthma, the most common chronic disease, is characterized by airway inflammation and airflow obstruction. The World Health Organization estimates that approximately 300 million people worldwide have asthma, 30% of whom are pediatric patients. Asthma is a major cause of morbidity that can lead to hospitalization or death in severe pediatric cases. Therefore, it is necessary to provide children with objective and reliable treatment according to consistent guidelines. Several institutes, such as the Global Institute for Asthma, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, British Thoracic Society, Japanese Society of Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Clinical Immunology have published and revised asthma guidelines. However, since recommendations differ among them, confusion persists regarding drug therapy for pediatric asthma patients. Additionally, some guidelines have changed significantly in recent years. This review investigated the latest changes in each guideline, compared and analyzed the recommendations, and identified the international trends in pediatric asthma drug therapy. The findings of this review may aid determinations of the future direction of the Korean guidelines for childhood asthma.

Key message

Asthma is the most common chronic disease among children. Although asthma in children may spontaneously improve, it continues into adulthood in many cases. Therefore, appropriate disease management and medication are essential. Consistent and objective guidelines are needed to manage pediatric asthma and related adverse reactions.

Introduction

Asthma, a heterogeneous disease characterized by chronic airway inflammation, is defined by symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough that vary over time in occurrence, frequency, and intensity [1]. The World Health Organization estimated that asthma affected 262 million individuals and caused 455,000 deaths worldwide in 2019 [2,3]. With current trends rising, this figure is expected to reach 400 million by 2045 [4]. Asthma in childhood is most common chronic disease and the leading cause of childhood morbidity as measured by school absences, Emergency Department (ED) visits, and hospitalizations [4]. Asthma in children ranks among the top 20 conditions worldwide in terms of disability-adjusted life years [5].

Climate change as well as rising temperatures and carbon dioxide levels favor pollen growth, which is associated with increased rates of asthma in children. Worldwide, 11%–14% of children aged 5 years and older currently report asthma symptoms; an estimated 44% of these cases are related to environmental exposure [3]. Air pollution, secondhand tobacco smoke, indoor mold, and dampness exacerbate asthma in children [3].

Epidemiology

The accurate prevalence of asthma in children worldwide was reported by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC), in which Korea also participated [6-8]. The study revealed an increasing prevalence of doctor diagnoses but a decreasing prevalence of asthma symptoms in elementary school students. A 2010 Korean study found higher asthma rates in 6–7 year-olds (10.3% vs. 5.8% in 2000) but little change in 13–14 year-olds (8.3% vs. 8.7%) [9].

According to the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service's Health and Medical Big Data Open System, 663,708 patients were coded as having "J45 asthma" in 2021. Among them, those younger than 9 years of age accounted for the highest proportion (20.6%) (Fig. 1) [10]. Data from 2010 to 2021 also showed that, among patients who received asthma treatment, the highest proportion were aged 0–9 years (Fig. 2A). Among children and adolescents, those younger than 5 years of age had the highest rate of asthma treatment, followed by those aged 5–9 years (Fig. 2B) [10]. The particularly high frequency of asthma treatment in the 0–4 years age group is believed to be associated with the common use of nebulizer treatments for asthma as well as conditions such as bronchiolitis or pneumonia. According to cause of death statistics from the Korean Statistical Information Service, the asthma-related mortality rate in Korea increased in 2002 and then continued to decline. Patients aged 0 years showed a peak incidence of 2.2 per 100,000 in 2002, while those aged 1–4 years showed a peak incidence of 0.8 per 100,000 in 2001 that declined thereafter (Fig. 3) [11]. The decrease in pediatric asthma mortality can be attributed to various factors, including the early diagnosis and treatment of asthma, strengthened asthma education and prevention programs, reduced smoking rates, and environmental improvements. Together, these factors are likely to play a role in reducing pediatric asthma-related mortality.

Percentage of patients in Korea in 2021 diagnosed with asthma (disease code J45) by age group according to the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service's Health and Medical Big Data Open System.

(A) Estimated number of asthma treatments by age range, 2010–2021, according to the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service's Health and Medical Big Data Open System. (B) Estimated number of asthma treatments in children and adolescents by age group, 2010–2021, according to the National Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service's Health and Medical Big Data Open System.

Asthma mortality rate of children and adolescents in Korea, 2000–2021, according to the Korean Statistical Information Service.

Child asthma mortality rates have decreased in Korea; however, asthma remains an important cause of pediatric ED visits or hospitalizations. In a Korean study performed from 2002 to 2015, childhood asthma mortality decreased but mortality due to respiratory diseases was 4 times more common in patients with asthma than in healthy children aged >5 years [12]. Another study performed from 2007 to 2012 reported that 41,128 children and adolescents visited the ED due to acute asthma; moreover, the number of patients who visited the ED tended to increase annually, while the percentage of hospitalizations after ED examinations was 42.6% of the total number of ED visits [13].

Medical costs are also a problem among patients with asthma in Korea. The cost of medical care benefits for patients treated for asthma in 2021 was approximately 90 billion, of which 10 billion was for patients aged 0–9 years. The cost of medical care benefits for patients treated for severe asthma in 2016 was 16 billion won; this figure gradually decreased to 8 billion won by 2021. However, significant expenses are still allocated to asthma treatment. Of them, pediatric patients (0–9 years) account for approximately 2%–8% of cases (Fig. 4) [10]. Therefore, treatment focusing on proper disease management, patient education, and drug therapy for childhood asthma is essential. Poor asthma control leads to poor quality of life in children and their caregivers and possible progression to adulthood asthma [14]. Major institutions worldwide have compiled guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asthma. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) [1] and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines are representative [15]. These guidelines were updated in 2021 and 2020, respectively, and their main contents have changed somewhat. There are also British guidelines for managing asthma [16], Japanese guidelines for managing childhood asthma [17], European Respiratory Society clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis of children 5–16 years [18], and Korean guidelines for managing asthma [19]. However, the recommendations that vary slightly among them cause confusion in terms of drug therapy for patients with pediatric asthma. Therefore, this review introduces the latest recommendations from the GINA, NAEPP, British Thoracic Society (BTS), Japanese Society of Allergology and Japanese Society of Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy, and Clinical Immunology (KAAACI) guidelines. We also compared their contents to determine the latest treatment trends.

GINA guidelines

In 1993, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute collaborated with the World Health Organization to convene a workshop report, the Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, and then established the GINA guidelines. The GINA report has been updated annually since 2002; the new recommendations regarding the treatment of mild asthma published in 2021 may be the most fundamental change in asthma management guidelines in the past 30 years (Table 1). The changes made in 2021 are as follows1): The major change is that asthma should not be managed solely with short-acting beta2 agonists (SABAs); rather, all adults, adolescents, and children 6–11 years with asthma should be treated with therapies containing inhaled corticosteroids (ICS). The GINA treatment recommendation for adults and adolescents is divided into 2 tracks based on reliability: track 1, with low-dose ICS-formoterol as the reliever, is the preferred approach recommended by the GINA because of its ability to reduce the risk of severe exacerbations versus SABA but with similar symptom control and lung function [20,21]; and track 2, with SABAas the reliever if track 1 is not possible or not preferred by a patient with no exacerbations on their current therapy.

The preferred controller options for 6–11 years in step 1 is ICS whenever SABA is taken because this approach showed substantially fewer exacerbations than SABA-only treatment [22]. Likewise, the treatment figure now also includes maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) consisting of low-dose budesonide/formoterol, which demonstrated a large reduction in severe exacerbations with MART versus the same-dose ICS long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) or high-dose ICS [23]. For children up to 5 years of age, the initial management of wheezing episodes with SABA is recommended. Meanwhile, the GINA guidelines were updated in 2022 with new content [24]. The updates for adults and adolescents include anti-thymic stromal lymphopoietin (subcutaneous tezepelumab) for patients aged ≥12 years with severe asthma [25]. This new biologic agent can reduce severe exacerbations in those with high blood eosinophils or high fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) [25]. The updates for children aged 6–11 years include adding anti-interleukin 4 receptor (dupliumab) to the step 5 options for this age group [26]. The GINA guidelines were updated in 2023 [27]. The new term anti-inflammatory relievers (AIR), including as-needed ICS-formoterol and as-needed ICS-SABA, reflects the dual purpose of reliever inhalers. The 2023 guidelines distinguished between the as-needed use of AIR only in steps 1–2 and MART with ICS-formoterol in steps 3–5. It also recommends the addition of as-needed ICS-SABA to the 2023 GINA treatment recommendation for adults and adolescents. In the double-blind MANDALA study, the as-needed use of ICS-SABA increased the time to a first severe exacerbation by 41% versus the use of as-needed SABA [28]. Mepolizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 antibody administered by subcutaneous injection, was added to the preferred maintenance treatment options at step 5 for children with severe eosinophilic asthma [29].

NAEPP versus GINA guidelines

In 1989, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute created the NAEPP to facilitate the proper diagnosis and treatment of asthma. The most recent update to these guidelines in 2020 (Table 1) focused on the asthma management guidelines, particularly 6 selected topic areas [15]. The updated contents include the role of FeNO in the diagnosis, medication selection, and monitoring of treatment response in asthma; remediation of indoor allergens in asthma management; immunotherapy and management of asthma; adjustable ICS dosing in recurrent wheezing and asthma, long-acting muscarinic antagonists in asthma management as an add-on to ICS; and bronchial thermoplasty in severe adulthood asthma.

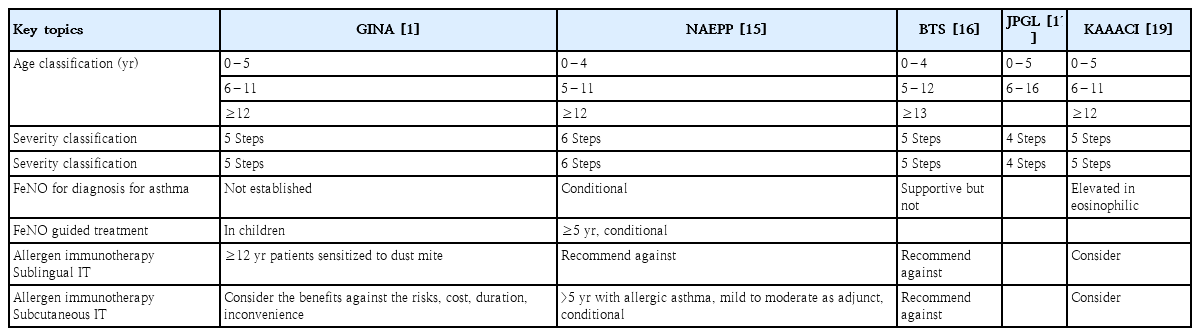

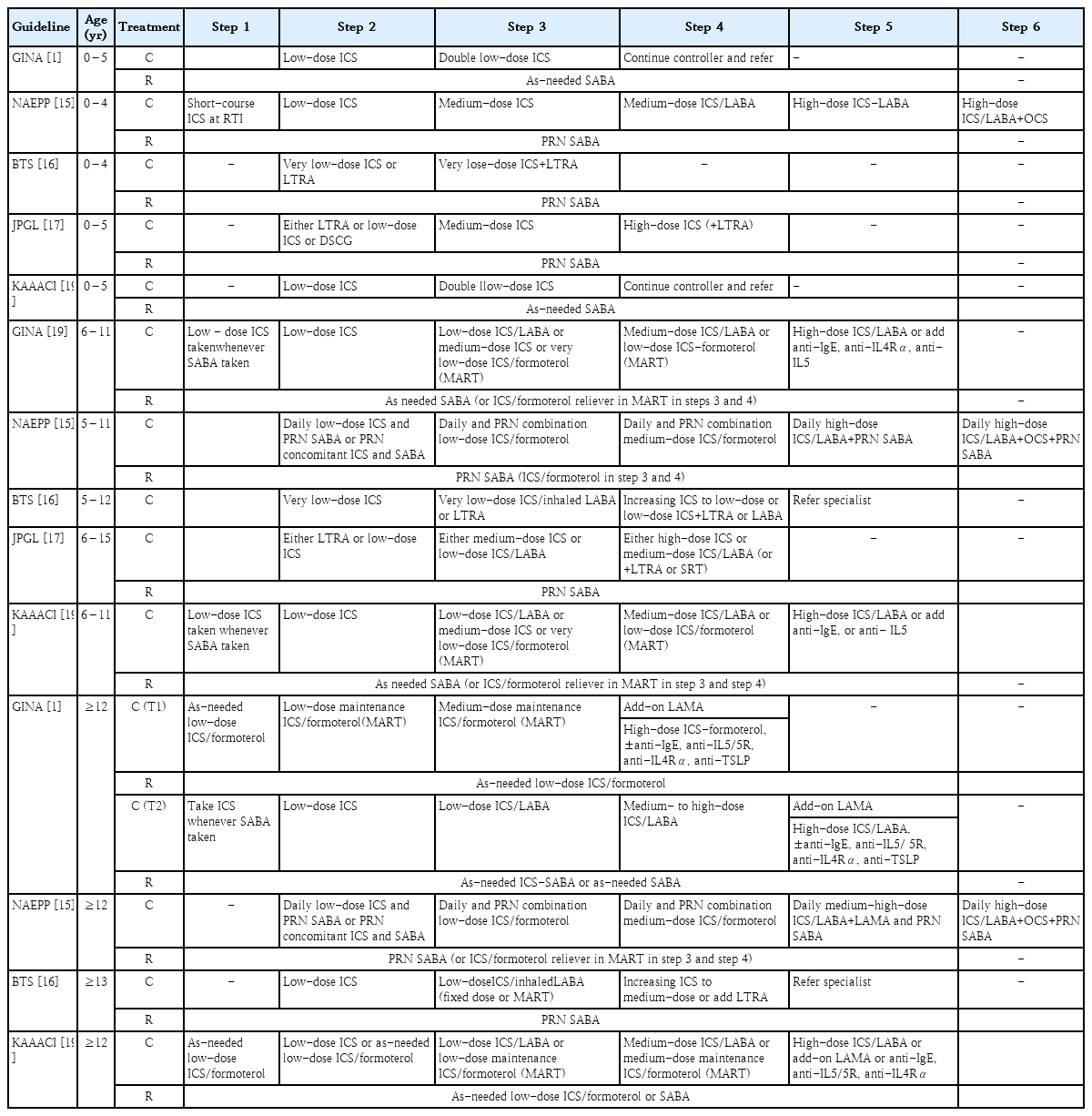

The GINA provides a comprehensive yearly updated document that reviews the current literature using evidence levels of A–D, but the NAEPP guidelines provide a focused approach with 19 recommendations covering 6 topics to address the GRADE methodology. The GINA and NAEPP use a stepwise approach to asthma management. The GINA emphasizes using a personalized approach to manage asthma; in contrast, the NAEPP retained the Expert Panel Report 3 diagrams and did not make updated recommendations except to continue assessing control, stepping up, or stepping down treatment. Both feature 3 age categories, with the GINA age categories being ≤5 years, 6–11 years, and ≥12 years. The NAEPP includes age ranges of 0–4 years, 5–11 years, and 12 years. Since the GINA combines mild asthma into a single category, it includes fewer steps in each age category (4 steps for children ≤5 years old and 5 steps for those aged 6–11 or ≥12 years) than the 6 steps for each age category of the NAEPP (Table 2).

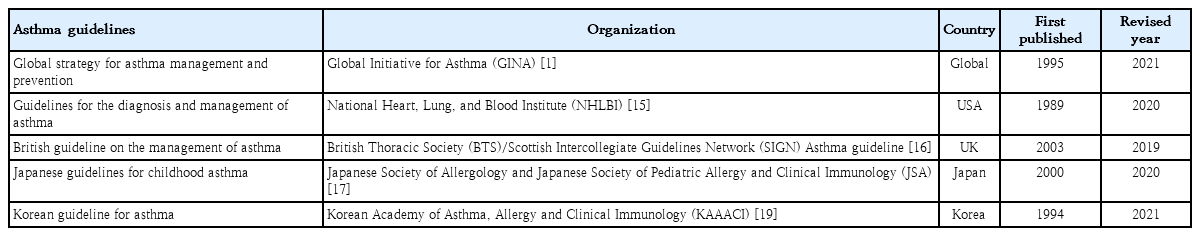

Key subjects of the GINA (2021), NAEPP (2020), BTS (2019), JPGL (2020), and KAAACI (2021) guidelines

In the GINA, the current definition of asthma severity is based on a retrospective assessment after at least 2–3 months of control treatment. The GINA sets 5 severity levels, whereas the NAEPP sets 6 severity levels. Both guidelines classify severity based on clinical assessments and regional factors, and it is essential to adjust treatment plans by considering the patient's condition and the relevant guidelines (Table 2). Both guidelines support the use ofFeNO as an adjunct to assist in deterring airway inflammation (Table 2).

For patients <5 years of age, the NAEPP suggests using short-course ICS during the respiratory tract infection (RTI) period in step 1, whereas the GINA suggests using pro re nata (PRN) SABA in step 1. Both guidelines used ICS as a controller from step 2, but in step 2, the GINA suggests using short-course ICS during the RTI. The NAEPP suggests that LABA be added in step 4, whereas the GINA does not recommend LABA for this age group. In the 6–11 years age group, the GINA suggests the simultaneous use ofICS when using SABA in step 1, whereas the NAEPP recommends using PRN SABA. Both guidelines suggest MART therapy from step 3; Single MART is advocated by the GINA for patients >6 years of age and by the NAEPP for those >4 years of age [23].

For patients ≥ 12 years of age, the GINA divides treatment strategies into 2 tracks according to reliability. In step 1, the GINA suggests the use of as-needed ICS-formoterol or both SABA and ICS simultaneously, whereas the NAEPP suggests the use of PRN SABA. In patients aged ≥12 years, in step 2, the NAEPP recommends either daily low-dose ICS and as-needed SABA or as-needed ICS and SABA used concomitantly. Both guidelines recommend the preferred status for ICS-LABA versus ICS-LAMA in steps 3 (NAEPP) and 4 (NAEPP and GINA). However, the GINA emphasizes the importance of increasing ICS-LABA to at least a medium dose before considering the addition of LAMA. The NAEPP designates triple therapy (ICS+LABA+LAMA) as the preferred step 5 therapy, while the GINA considers it the preferred option including biologic therapy (Table 3) [30].

Treatment steps of the GINA (2021), NAEPP (2020), BTS (2019), JPGL (2020), and KAAACI (2021) guidelines

In the case of immunotherapy, the NAEPP and GINA appear to take opposite stances. The NAEPP guidelines conditionally recommend the use of subcutaneous immunotherapy (SCIT) as an adjunctive treatment to standard pharmacotherapy in patients with controlled asthma and allergic triggers for ≥5 years. Conversely, the GINA appears to stress the potential side effects and disadvantages of SCIT.In contrast, the GINA conditionally recommends the addition of sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) for adult patients with allergic rhinitis and sensitization to house dust mites (forced expiratory volume in 1 s >70%)(Table 2).

BTS versus GINA guidelines

In 1999, the BTS and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network agreed to jointly produce comprehensive asthma guidelines. The outcome of these efforts was the British Guideline on the Management of Asthma published in 2003 [31]. The last updated guideline was published in 2019 (Table 1). Similar to the GINA guidelines, the BTS guidelines classify disease severity into 5 stages (Table 2); however,there are several differences between the guidelines. The GINA recommends the ICS dose based on the component name [1], whereas the BTS indicates the dose instead of component name for each product name [16]. Unlike the GINA, the BTS recommends inhaled SABA as a short-term reliever therapy for all patients with symptomatic asthma. Although inhaled SABA quickly and effectively relieve asthma symptoms [32], patients with asthma treated with SABA alone (versus ICS) are at an increased risk of asthma-related death [33,34] and urgent asthma-related episodes [35], even if they have good symptom control [36].

Moreover, in step 2, the GINA recommends low-dose ICS with the addition of LABA or a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) when the symptoms worsen. In addition, an increase to medium-dose ICS or addition of very-low-dose MART is recommended [1]. However, the British guidelines recommend the initial addition of LABA or LTRA to very-low-dose ICS in step 3 followed by an increase to low-dose ICS if no symptom improvement is noted. The GINA does not state that theophylline carries a higher risk of side effects, whereas the BTS states that theophylline has some beneficial effects [37,38]. While the GINA does not recommend chromones (nedocromil sodium and sodium cromoglycate) because they have a favorable safety profile but low efficacy [39-41], the BTS recommends them for patients >5 years of age.

Tiotropium bromide in addition to ICS+LABA, compared with ICS+LABA alone, reportedly resulted in fewer asthma exacerbations and improved lung function [42]. The GINA recommends tiotropium for patients aged ≥6 years, whereas the BTS recommends its use for those aged ≥12 years. The GINA recommends that house dust mite SLIT and the NAEPP recommends SCIT, whereas the British guidelines do not recommend immunotherapy (Table 2) [16]. Although there are beneficial effects of using SLIT or SCIT in the management of asthma, it is not recommended because of significant side effects, a lack of data on its long-term effectiveness, and concerns about study quality [43-45].

Japanese Pediatric GuideLine versus GINA guidelines

The Japanese Pediatric GuideLine (JPGL) recommends its own strategy that differs significantly from those of the GINA and NAEPP. The original JPGL was published in 2000 by the Japanese Society of Pediatric Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and several revisions were published thereafter. The Japanese Guideline for Childhood Asthma 2020 is a translation of the Japanese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Allergic Diseases 2017 into English (Table 1) [17]. Unlike the GINA, the JPGL 2017 classifies patients into children ≤5 years of age and those 6–15 years of age. The GINAsets 5 severity levels, whereas the JPGL sets it to 4 levels (Table 2). The severity of pediatric asthma is lower in Japan than in the United States. Therefore, according to the GINA, intermittent severity is defined as symptoms occurring less than twice a month. In contrast, the JPGL classifies intermittent severity as having 2 or 3 coughing and/or wheezing episodes per year. Consequently, in terms of intermittent severity, step 1 of the GINA aligns with step 2 of the JPGL (Table 2).

The GINA and JPGL guidelines also differ in terms of recommended drug therapy (Table 3). Unlike the GINA, the JPGL guidelines recommend LTRA or cromolyn as additional therapy in step 1 in children <5 years of age. Moreover, the JPGL recommends LTRA, low-dose ICS, or disodium cromoglycate (≤5 years of age)for all patients with symptomatic asthma. The JPGL considers the efficacy of LTRA as equal to that of ICS and proposes it as an effective first-line preventer [46]. In children 6–15 years of age, the JPGL recommends medium-dose ICS or low-dose salmeterol/fluticasone combination (SFC) in step 3. Unlike the GINA, which prefers budesonide/formoterol, JPGL proposes SFC in step 3.

The GINA states that, in addition to ICS or SFC, either LTRA or slow-release theophylline should be considered. The JPGL recommends the use of theophylline from stage 3 in patients aged 6–15 years, while the GINA recommends the use of theophylline for pediatric patients aged >12 years. The GINA reflects the international trend of slightly reducing the use of theophylline in pediatric patients with asthma because of adverse reactions; rather, in step 4, high-dose ICS+LTRA should be considered. Finally, the JPGL states that, if a patient <5 years of age has more symptoms, patched beta2 agonist can be considered as short-term additional therapy (Table 3) [47].

KAAACI versus GINA guidelines

The KAAACI has been developing guidelines for asthma treatment in Korea. Starting with its first publication in 1994, it produced a revised version every time there was a significant change in asthma knowledge (2007, 2011, and 2015). The 2021 KAAACI guidelines for asthma referred to the revised GINA guidelines published in 2021 [19]. The KAAACI and GINA guidelines were generally consistent in the disease classification system, treatment type, recommended dose, and step-up and step-down methods according to patient symptoms. The changes to the treatment of children and adolescents in the 2021 KAAACI guidelines are as follows. The previous 2015 guidelines recommended the use of sustained-release theophylline for those aged ≥6 years, while the 2021 guidelines recommend that pediatric patients aged ≥12 years use it as recommended by the GINA. Previous guidelines included no recommendations for the use of tiotropium; however,this 2021 guideline recommends that tiotropium be added as a mist inhaler for patients aged ≥6 years as in the GINA. In addition, treatments such as anti-immunoglobulin E (omalizumab) and anti-interleukin 5 (mepolizumab) may be added for patients aged ≥6 years in step 5 as in the GINA (Table 3).

Conclusion

This review compared the guidelines issued by the GINA and representative institutions in major countries such as the United States,the United Kingdom, and Japan. Although our findings confirm that the purpose of asthma management according to all of them involved achieving good symptom control and minimizing the risk of asthma-related morbidity and mortality, some important differences among guidelines were identified.Identifying the differences among guidelines and incorporating the necessary information will help promote the development of universal guidelines that can improve treatment adherence. In addition, thorough and continuous research is necessary to collect opinions on the latest asthma drug therapies and facilitate the development of internationally consistent guidelines. In conclusion, asthma guidelines should be further developed to reduce confusion in clinical and educational situations and provide objective and reliable drug therapy to children vulnerable to diseases and harmful reactions.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.