Kawasaki disease in infants

Article information

Abstract

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute febrile illness that is the predominant cause of pediatric acquired heart disease in infants and young children. Because the diagnosis of KD depends on clinical manifestations, incomplete cases are difficult to diagnose, especially in infants younger than 1 year. Incomplete clinical manifestations in infants are related with the development of KD-associated coronary artery abnormalities. Because the diagnosis of infantile KD is difficult and complications are numerous, early suspicion and evaluation are necessary.

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute febrile vasculitis. The peak incidence of KD is from 6 months to 2 years of age, which includes approximately 50% of all KD patients1,2). The proportion of KD patients younger than 6 months of age in relation to all KD patients is approximately 10%3,4), which is similar to the 11.2% in Japan5) and 7.7% in Korea6). In addition, the incidence of KD patients younger than 3 months of age was 1.7% in Japan5) and 2.2% in Korea6). The incidence of KD is very low in patients younger than 3 months of age3,4) or older than 8 years of age7), and few cases of KD in the neonatal period have been reported8).

Incomplete KD is more common in infants than in older children. Additionally, because of their higher risk for developing coronary artery abnormalities, precise diagnosis is important4). The diagnosis of infantile KD can be particularly difficult due to obscure clinical manifestations. This paper is a review with a special focus on infantile KD.

What is the significance of KD in children?

KD is the predominant cause of pediatric acquired heart disease in developed countries9). Cardiac lesions, such as coronary artery aneurysms, are a hallmark of KD10-12). Coronary artery complications develop in up to 25% of affected children if the disease is left untreated13,14), and these lead to mortality in approximately 2% of cases15,16). Prevention of aneurysms is the primary target for pediatricians treating patients with KD. Prompt diagnosis and the administration of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) can reduce the incidence of coronary artery abnormalities from 25% to 5%17).

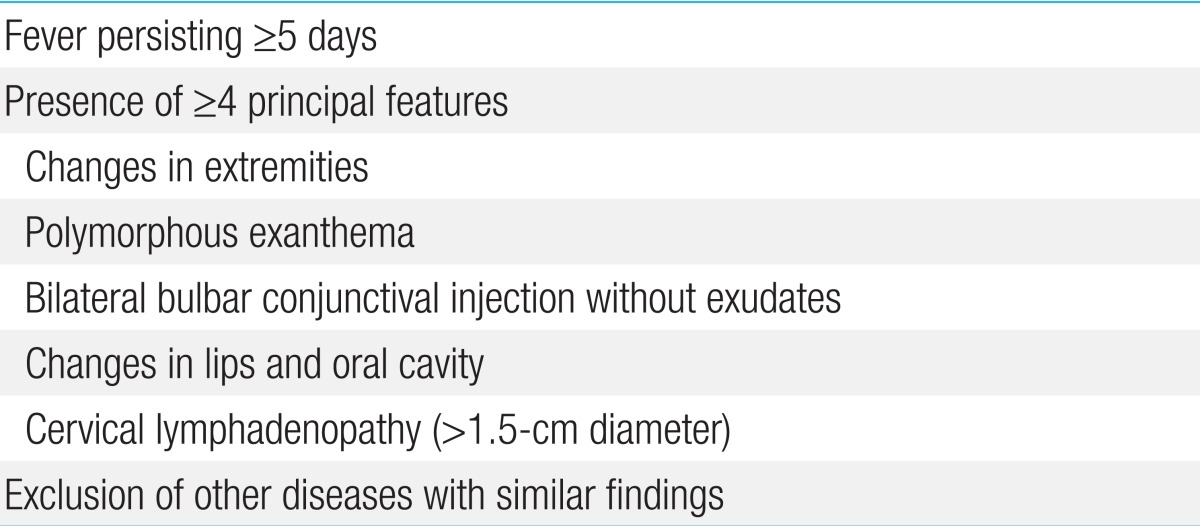

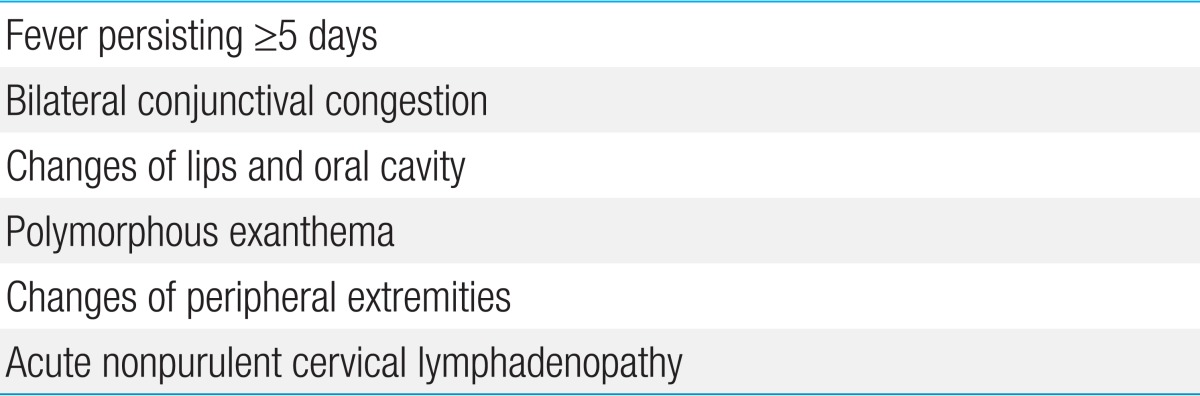

To establish a diagnosis, physicians depend on the diagnostic criteria, based on the typical combination of clinical presentations, formulated by the American Heart Association (AHA) (Table 1)18) or the Japanese Kawasaki Disease Research Committee (Table 2)19). However, it is becoming evident that all criteria for KD need not be present at the same time and can appear in sequence. For this reason, the diagnosis of KD is based on a high index of clinical suspicion in cases that lack the typical criteria (incomplete KD). Because the diagnosis of KD is based upon nonspecific clinical signs and because definitive diagnostic test exists, timely identification is challenging.

KD should therefore be considered in the differential diagnosis of every child with fever of at least several days' duration, rash, and nonpurulent conjunctivitis, especially in children younger than 1 year old and in adolescents, in whom the diagnosis is frequently missed.

Experienced clinicians who have treated numerous KD cases can establish the diagnosis before day 4. Fever duration of less than 5 days, which can be achieved by early IVIG treatment, can be considered a principal symptom according to the Japanese criteria20).

Several studies have attempted to define risk factors for the development of coronary artery abnormalities in children with KD. Identified risk factors include incomplete presentation, delay in diagnosis, duration of fever before treatment, male sex, young and older age, and IVIG resistance21,22). Incomplete clinical manifestations in infants and IVIG nonresponsiveness in the older children are particularly associated with the development of KD-associated coronary artery abnormalities23). Most studies also point to the timing of therapy as a critical factor in the development of coronary artery abnormalities.

Why is infantile KD important?

Infants younger than 1 year tend to show fewer clinical manifestations of the disease, and various features are common by age group. Some studies found that typical mucosal and lymph node changes were absent in infants younger than 6 months. Patients younger than 6 months also had a lower incidence of strawberry tongue and indurative edema of the palms and soles compared with older patients24,25).

The diagnosis of KD is difficult in infants because its presentation is usually atypical and similar to that of other diseases. In our experience, distinguishing between KD and enteroviral meningitis in febrile infants with cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis poses a diagnostic challenge26). We identified longer duration of fever before admission, higher absolute neutrophil count, increased C-reactive protein (CRP) level, pyuria, and less prominent cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis as initial features of infants finally diagnosed with KD26). We also encountered the unusual case of infantile parotitis unresponsive to antibiotics and accompanied by prolonged fever that was diagnosed as incomplete KD with coronary complications27).

The current guidelines recommend that infants aged 6 months or younger with fever for 7 days or longer without other explanation should undergo laboratory investigation for indicators of a systemic vascular response (i.e., erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], CRP level)28).

KD is frequently associated with elevation of inflammatory markers including ESR, CRP, and platelet count. Other laboratory findings such as high white blood cell (WBC) count (neutrophilic type), nonseptic pyuria, low sodium levels, hypoalbuminemia, or elevated liver enzymes may supplement the diagnosis29).

KD is rare in infants younger than 3 months of age. The presumptive explanations for this phenomenon include the protective effect of passive immunity transmitted from the mother and the lower possibility of exposure to unknown airborne pathogens because the infants live indoors.

Some studies have reported that infants younger than 6 months old take the longest time to diagnose, are the least likely to fulfill the major clinical criteria, and have the least favorable laboratory results, all of which are risk factors for developing coronary artery abnormalities3,4,30). Coronary artery aneurysm is more frequently observed in infants younger than 6 months, although not statistically significant. Patients younger than 1 year old have more frequent high WBC count and sterile pyuria, but less neck lympadenopathy30). Because many infants present atypically, KD should be considered in all children of 1 year or less with prolonged fever, extreme platelet count elevation, and no compelling alternative diagnosis30,31).

Witt et al.32) concluded that coronary artery abnormalities were more common in cases who did not meet the criteria (20%) compared with those who had the complete clinical presentation (7%). Despite the potential risks of overdiagnosis and overtreatment, this practice seems justified because the complete criteria are an insensitive indicator of having or developing coronary artery abnormalities.

In a retrospective study of 562 patients diagnosed with KD at 8 North American centers, 16 percent were diagnosed after the first 10 days of the illness (i.e., late diagnosis)33). Predictors of delayed diagnosis of KD included age below 6 months, clinical presentation of incomplete KD, greater distance from a tertiary center, and variability between clinical centers. The results of this study underscore the need for a high index of suspicion of KD, especially in infants and patients who present with incomplete KD, in order to identify and treat patients in a timely manner.

These age-specific characteristics could aid customization of the diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in KD, thereby helping to improve the outcome of the disease.

What does incomplete KD in infants mean?

The term "atypical KD" has recently been used to describe patients with an incomplete presentation of the disease, regardless of the presence of coronary complications34,35), and is interchangeable with "incomplete KD." In the absence of a specific test, the diagnosis of clinically incomplete KD based on the history, physical examination, and clinical laboratory results can be challenging.

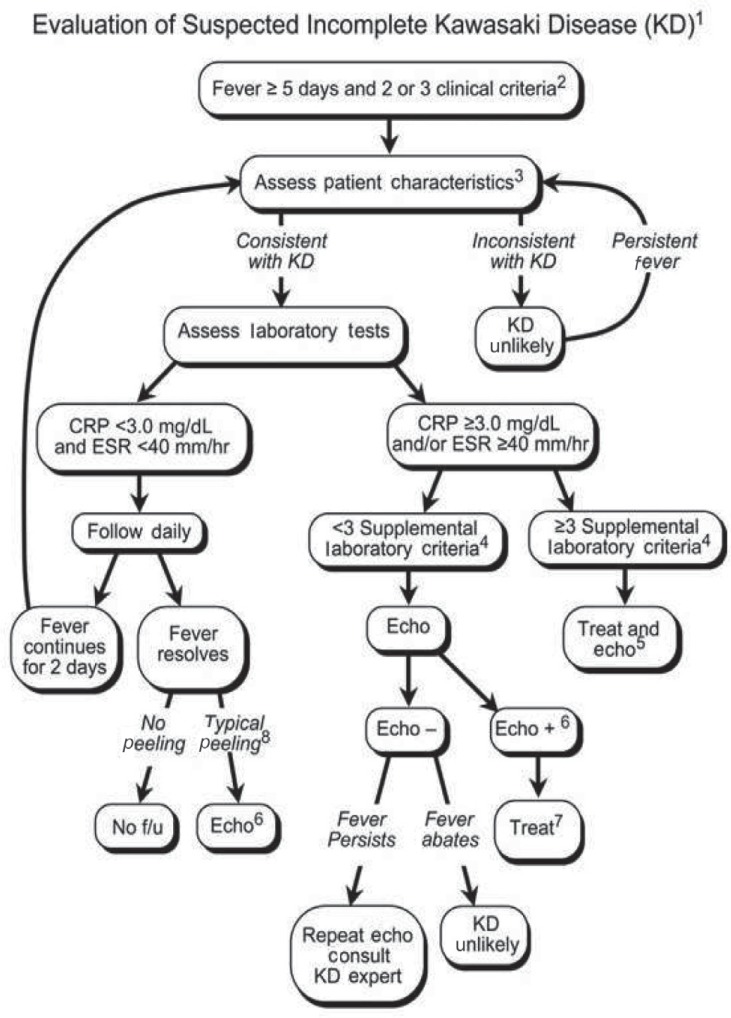

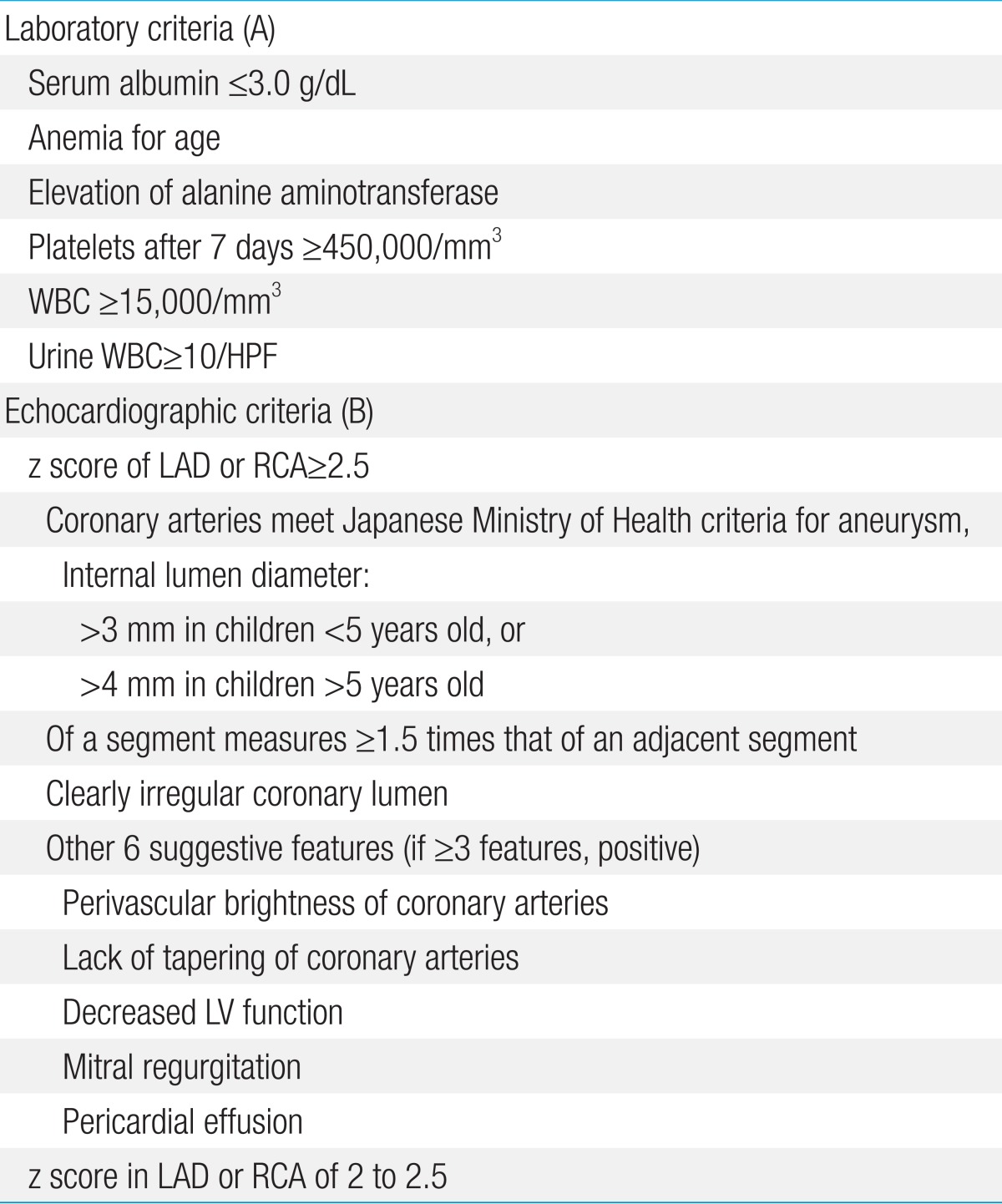

Using the algorithm of the AHA for the diagnosis of incomplete KD (Fig. 1)14), echocardiography should be performed in presentations with evidence of systemic inflammation, even if there are no clinical criteria of KD. This algorithm is offered as guidance to clinicians until an evidence-based algorithm or a specific diagnostic test for KD becomes available. Echocardiography and IVIG administration should be considered if the CRP level is 3 mg/dL or higher or if the ESR is 40 mm/hr or greater14). The AHA recommended a diagnostic algorithm of incomplete KD, which consists of 6 supplemental laboratory and echocardiographic criteria (Table 3)14,36). The presence of more than 3 laboratory criteria supports the diagnosis of incomplete KD (Table 3A). An echocardiogram is considered diagnostically positive if any of the 3 conditions mentioned in Table 3B are met.

Evaluation of suspected incomplete Kawasaki disease. 1) In the absence of a gold standard for Kawasaki disease diagnosis, this algorithm cannot be evidence based but rather represents the informed opinion of the experts committee. Consultation with an expert should be sought anytime assistance is needed. 2) Infants ≤6 months old with fever for ≥7 days without any explanation should undergo laboratory testing, and if evidence of systemic inflammation is found, echocardiography should be performed, even if the infants have no clinical criteria. 3) Patient characteristics suggestive of Kawasaki disease are listed in Table 118,36). Characteristics suggestive of a disease other than Kawasaki disease include exudative conjunctivitis, exudative pharyngitis, discrete intraoral lesions, bullous or vesicular rash, or generalized adenopathy. An alternative diagnosis should be considered. 4) Supplemental laboratory criteria include albumin ≤3.0 g/dL, anemia, elevation of alanine aminotransferase, platelet count ≥450,000/mm3 after 7 days, WBC count ≥15,000/mm3, and WBC in urine ≥10/high-power field. 5) Treatment can be undertaken before performing echocardiography. 6) The echocardiogram is considered positive for the purpose of this algorithm if any of the following 3 conditions are met: (1) z score of LAD or RCA ≥2.5; (2) the coronary arteries meet the Japanese Ministry of Health criteria for aneurysms; and (3) ≥3 other suggestive features exist, including perivascular brightness, lack of tapering, decreased LV function, mitral regurgitation, pericardial effusion, or z scores in LAD or RCA of 2-2.5 (Table 3)14,36). 7) If the echocardiogram is positive, treatment should be given to children within 10 days of fever onset and those with fever beyond day 10 with clinical and laboratory signs (CRP, ESR) of ongoing inflammation. 8) Typical peeling begins under the nail bed of the fingers and then the toes. WBC, white blood cell; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery; LV, left ventricular; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; f/u, follow-up. Reproduced from Newburger JW, et al. Pediatrics 2004;114:1708-33, with permission of American Academy of Pediatrics14).

Supplemental laboratory criteria (A) and echocardiographic criteria (B) for the diagnosis of incomplete Kawasaki disease

A recent report describes some problems with an excessively restrictive definition of incomplete presentation36). Patients who had fever with less than 4 characteristic manifestations were diagnosed with incomplete KD when 2-dimensional echocardiography detected coronary artery involvement. A delay of management may be induced by postponing diagnosis of incomplete presentations until coronary artery abnormality is confirmed. It is now recognized that a large number of patients with KD do not fulfill full clinical KD criteria (i.e., incomplete KD) and that up to 20% of patients who are treated for KD are incomplete cases5,14,37,38).

Chang et al.4) showed higher coronary complications in infants less than 6 months old diagnosed as incomplete KD. Park et al.6) also reported differences between patients with KD younger and older than 6 months in the incidence of coronary artery abnormalities (21.0% vs. 18.7%) and coronary artery aneurysms (4.7% vs. 3.1%), respectively.

However, Lee et al.39) studied the incidence of coronary artery lesions in KD patients younger than 3 months of age and older than 3 months of age and found no significant difference in the prevalence of coronary artery dilatation (19.9% vs. 18.7%) or coronary artery aneurysms (3.4% vs. 2.6%), respectively. They speculated that this unexpected result was because of the very small number of patients younger than 3 months of age among all KD patients, because the majority of pediatricians have a high index of suspicion for incomplete KD, and because early diagnosis can reduce the incidence of incomplete KD in Korea.

Currently, the diagnosis of incomplete KD can be made in cases with fewer classical diagnostic criteria and with several compatible clinical, laboratory, or echocardiographic findings after the exclusion of other febrile illnesses.

Some studies state that almost half of the patients with coronary artery abnormalities were incomplete cases14,40). The high incidence of incomplete KD raises the concern that many cases of KD may be undiagnosed and untreated. The risk of delayed diagnosis and management in young infants with an incomplete presentation has been indicated previously41-44).

Risk factors for incomplete KD are not well established. However, males and children of Asian ancestry appear to have the highest risk, which is consistent with the risk factors for complete presentation. Sudo et al.28) compared clinical risk factors for coronary artery lesions in patients with both incomplete and complete presentations of KD and showed that late IVIG administration (≥7 days of illness) was a significant risk factor for the development of coronary artery lesions in both groups. Infantile KD patients also may have more severe coronary abnormalities and a slower resolution than older children. In addition, diastolic function might be vulnerable to impairment in the infant group based on mitral inflow and tissue Doppler echocardiographic studies45).

The higher rate of incomplete KD in infants may originate from their weakened responses to vasculitis due to an immature immune response, neutralization of superantigen by maternal antibody transferred through the placenta, and cross-reaction to antibody produced by frequent active immunity4). KD should therefore be considered in any infant or child, primarily if younger than 6 months old, with persistent and unexplained fever and laboratory evidence of systemic inflammation, even without more clinical criteria suggestive of the disease, because early recognition and treatment may prevent development of coronary artery dilatation and aneurysm formation. The clinical challenge lies in distinguishing cases of KD that do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria from those that strongly resemble a variety of common childhood disorders.

Conclusions

The majority of coronary artery abnormalities in children with KD have been identified at initial echocardiography during the first week of illness. KD must be considered when prolonged fever is present, mainly in young infants in whom the incomplete forms of the disease are more frequent. A diagnostic approach that includes a high index of suspicion for very young infants who have a high fever with no definite clinical presentations of KD is therefore crucial to prevent coronary artery abnormalities. The majority of the "high-risk" patients (i.e., those who develop coronary artery abnormalities) might be identifiable by echocardiography at the time of initiation of therapy.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.