Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among parents of neonates admitted to neonatal intensive care unit: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Article information

Abstract

Background

Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission causes significant distress that can hinder the successful transition into parenthood, child-parent relations, and child development.

Purpose

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to understand parental psychological phenomena. Here we assessed the emotional response of parents of newborns during NICU admission.

Methods

Two authors independently searched the PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Clinical Key, and Google Scholar databases for studies published between January 01, 2004, and December 31, 2021. The review followed Cochrane collaboration guidelines and the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis) statement. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. Stata software (version 16) was used to compute the results.

Results

This review comprised 6,822 parents (5,083 mothers, 1,788 fathers; age range, 18–37 years) of NICU patients. The gestational ages and neonatal weights were 25.5–42 weeks and 750–2,920 g, respectively. The pooled prevalence of anxiety was higher among mothers (effect size [ES], 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.41–0.61; and heterogeneity [I2]=97.1%; P<0.001) than among fathers (ES, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.11–0.42; I2=96.6%; P<0.001). Further, the pooled prevalence of depression was higher among mothers (ES, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.24–0.38; I2=91.5%; P<0.001) than among fathers (ES, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03–0.22; I2=85.6%; P<0.001). Similarly, the pooled prevalence of stress was higher among mothers (ES, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.31–0.51; I2= 93.9%; P<0.001) than among fathers (ES, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.09–0.34; I2=85.2%; P<0.001).

Conclusion

NICU admission is more stressful for mothers than fathers and can affect mental health and quality of life. Mothers reported a higher pooled prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression than fathers, possibly attributable to their feelings about birthing a sick child.

Key message

Question: What emotions do parents experience when their newborns are admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)?

Finding: Mothers experienced more anxiety (51%), depression (31%), and stress (41%) symptoms than fathers (26%, 12%, and 22%, respectively).

Meaning: Parents often experience anxiety, stress, and depression following NICU admission. Healthcare workers are responsible for providing regular parental counseling.

Introduction

The diagnosis of an illness in a child causes significant distress to parents. The grief is further aggravated when an infant is admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The NICU provides specialized and integrated care to infant who require close supervision and life support equipment to ensure normal body function. Parents fear the diagnosis and prognosis of illness, the associated medical risks, being separated from their child, the unfamiliar hospital environment, and hindrances accessing information and communicating with healthcare professionals. Although resilience varies among parents, distress can negatively impact the successful transition into parenthood, child- parent relationship, and child development [1,2].

Earlier studies reported mental health problems among parents of NICU infants, while recent studies reported the prevalence of anxiety and posttraumatic stress among parents of NICU babies [1,2]. Healthcare centers tend to ignore the mental health of primary caregivers of hospitalized patients. However, sick newborns require immediate intervention to reduce complications. Most infants admitted to the NICU require long-term care. Therefore, parental involvement and effective communication during NICU admission may increase their satisfaction and lead to continued care after discharge.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of recent studies published worldwide. In contrast to previous studies, this review focused on mental health problems among parents of neonates admitted to the NICU. However, understanding parental reactions to hospitalization is essential to healthcare providers offering appropriate interventions. Furthermore, we recognized the importance of separately examining anxiety, depression, and stress levels in mothers and fathers. This systematic review and meta- analysis aimed to understand the psychological phenomena experienced by parents of newborns during NICU admission.

Methods

1. Protocol and registration

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines the PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses) statement [3,4]. The review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022301340).

2. Search strategy and study selection

The search strategy was developed using a combination of MeSH (medical subject heading) terms and keywords (mother OR father OR parents OR maternal OR NICU mother OR NICU father OR lactation mother OR newborn mother OR NICU parents OR preterm mother) AND (anxiety OR fear OR nervousness OR depression OR hopelessness OR sleep problem OR afraid OR sttabress OR uneasiness) AND (NICU unit OR hospitalization OR NICU OR neonatal unit). The first 2 authors independently searched the PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Embase, Clinical Key, and Google Scholar databases for studies published between January 01, 2004, and December 31, 2021. The reference lists of all relevant studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria as well as related systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and review articles were manually searched. Duplicate records were excluded by title and abstract screening. The remaining original full-text articles were screened against the inclusion criteria.

Articles that fulfilled the following criteria were included in the review: observational studies whose participants were parents of children undergoing NICU treatment; studies that adopted standardized measurement tools; and studies that reported cutoff scores for anxiety, depression and stress among NICU parents. Studies that evaluated the efficacy of various interventions for stress, anxiety, and depression among parents of NICU patients were excluded. Any disagreements between the first 2 authors (AS and KH) regarding the data extracted from the articles were referred to the third author (AI), and dissimilarities were resolved in discussion with the third reviewer. The data extraction form included the first author’s name, year of study, country in which the study was conducted, sample size, parental age and educational level, infant’s gestational age and birth weight, instruments used during data collection with cutoff scores, and study outcomes.

3. Search outcome

The search identified 6,518 studies from online databases and 6 from printed materials. A total of 1,541 duplicate records were removed before the first screening. Further, 4,812 were rejected for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The full-text review eliminated 131 articles. The reasons for exclusion included a lack of sample size, time of data collection (when the neonate was admitted to/discharged from the NICU), participant characteristics, measurement tools, cutoff scores, and study outcomes. Finally, 41 articles were included in this meta-analysis. A summary of the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

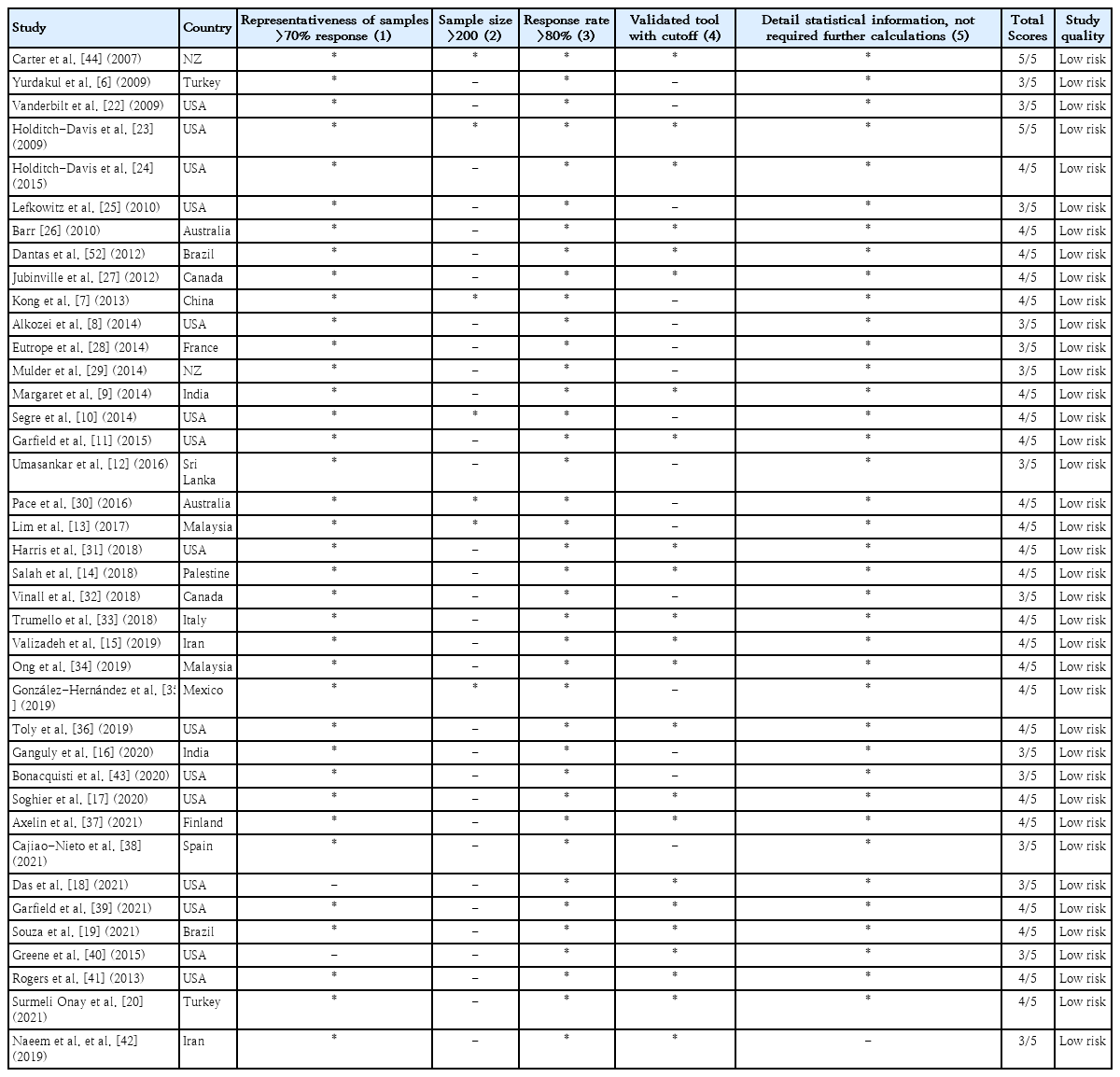

4. Quality assessment of included studies

The quality of the includefigd studies was assessed using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [5]. Each included study was appraised for selection, comparability, and outcomes. The scores on the assessment tool were 0–5. Studies that achieved a score of ≥3 were considered to have a low risk of bias. The appraisals of the included studies are presented in Table 1.

5. Parental anxiety, depression, and stress

Parents of NICU patients often experience mental distress due to being away from their newborns, financial obligations, and family responsibilities. Anxiety, depression, and stress were the primary outcomes of the included studies. The authors of the primary studies employed various scales to evaluate parental anxiety, including the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Beck’s Anxiety Inventory, Hamilton Anxiety Rating, and Self-Rating Anxiety Scale.

Similarly, depression and stress were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; Beck’s Depression Inventory; Center for Epidemiologic Study Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; Parental Stress Scale; Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaires; Stanford Acute Stress Reaction Questionnaires; and Stress Disorder Checklist for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, respectively.

6. Statistical analysis

The first 2 authors (AS and KH) manually calculated the pooled prevalence across studies using Microsoft Excel. We then computed the pooled estimated prevalence using a random-effects model with 95% confidence interval (CI). Categorical or dichotomous variables are reported as percentages with values of P<0.05 considered significant. Study heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 values: high, >75; medium, 50–75; and low, <50.3) Furthermore, a subgroup analysis was performed across the included studies. All analyses were performed using Poisson distribution under the Metaprop function of Stata 16 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

1. Study characteristics

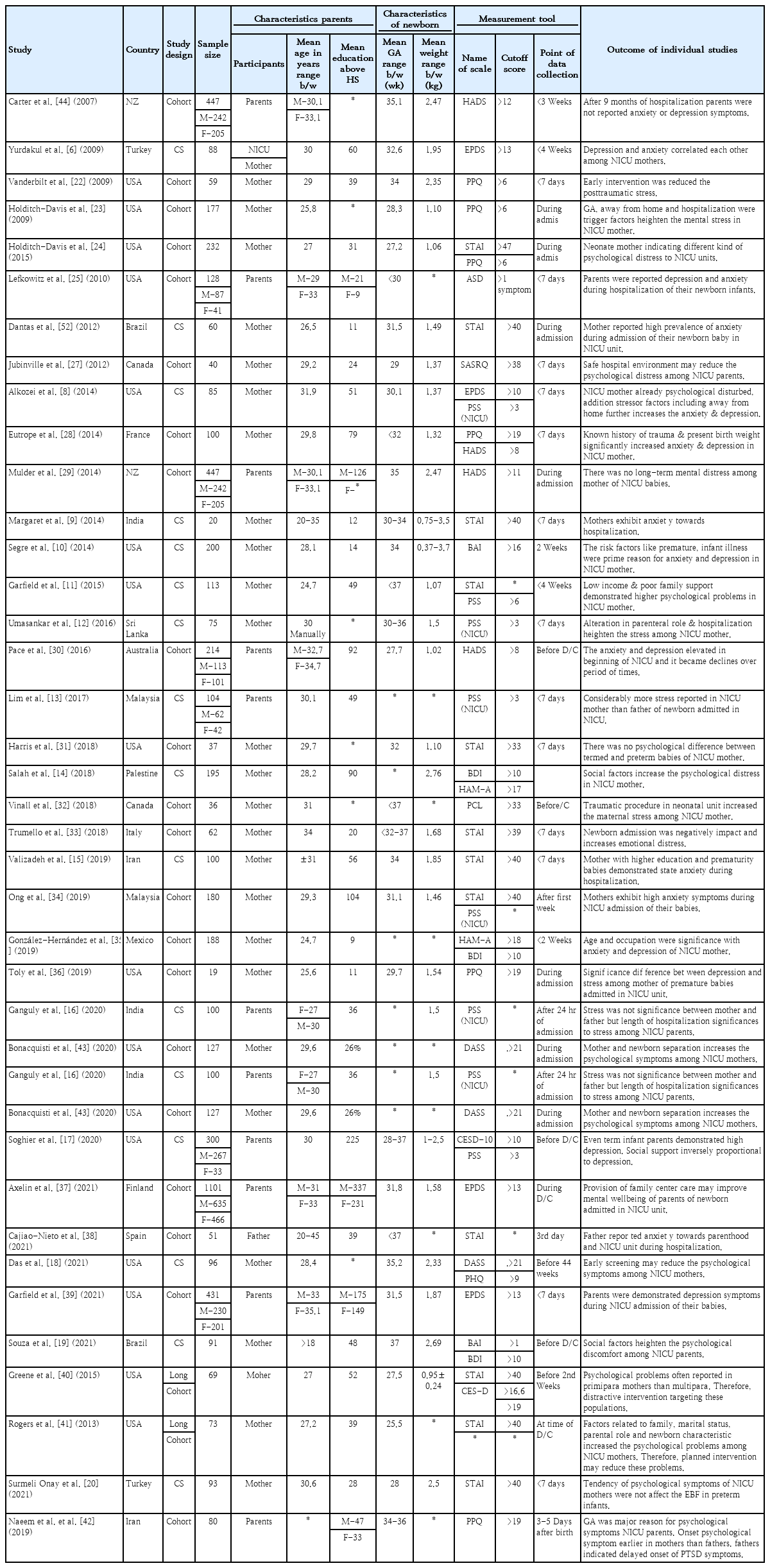

Pooled data from the included studies were organized for a systematic review and meta-analysis. A total of 39 studies met our inclusion criteria. Among the 39 included studies, 17 adopted a cross-sectional design and 22 used a prospective or longitudinal cohort design (Table 2) [6-43].

2. Participant characteristics

The review studies involved 6,822 participants (age range, 18–37 years), of whom 5,083 were mothers and 1,788 were fathers. The gestational age and neonatal weight ranges were 25.5–42 weeks and 750–2,920 g, respectively. Among the included studies, most participants were mothers, while one study included only fathers (Table 2) [39].

Among the included studies, 22 primary studies reported anxiety in the mother, 3 studies reported both fathers and mothers as participants, and one study reported anxiety in the father [29,38]. The pooled prevalence of anxiety was higher among mothers (effect size [ES], 95% CI, and heterogeneity [I2] (ES, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.41–0.61; I2=97.1%; P<0.001) [7,9-11,14,15,18-20,24,28-31,33-35,40,41,44] than fathers (ES, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.11–0.42; I2=96.6%; P<0.001) of NICU babies [29,30,38,44]. An overall subgroup analysis revealed that approximately 47% of parents were anxious about NICU admissions (ES, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.38–0.56; I2=97.1%; P<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Prevalence of anxiety among parents of newborns in neonatal intensive care unit. CI, confidence interval; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

The highest and lowest prevalence of anxiety in the included studies were reported among mothers of newborns admitted to the NICU at 13% and 93% respectively [22,31]. Similarly, the highest and lowest prevalence of anxiety among fathers of newborns admitted to the NICU were 0.09% and 46%, respectively (Fig. 2) [29,30].

3. Depression

Fathers typically experienced fewer depressive symptoms (ES, 0.12; 95% CI, 0.03–0.22; I2=85.6%; P<0.00) than mothers (ES, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.24–0.38; I2=91.5%; P<0.001) whose newborns were in the NICU [6,8,14,17-19,35,37,39-41,43]. An overall subgroup analysis revealed that 28% of parents were depressed about NICU admissions (ES, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.21–0.35; I2=94.6%; P<0.001) (Fig. 3).

Prevalence of depression among parents of newborns in neonatal intensive care unit. CI, confidence interval; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

The highest and lowest rates of depression among mothers in the included studies were 52% and 18%, respectively [8,43]. Similarly, the highest and lowest rates of depression among fathers in the included studies were 18% and 0.08%, respectively (Fig. 3) [39,43].

4. Stress

Mothers of newborns admitted to the NICU are more likely to experience stress (ES, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.31–0.51; I2= 93.9%; P<0.001) than fathers (ES, 0.22; 95% CI, 0.09–0.34; I2=85.2%; P<0.001 [8,12,13,16,17,21-28,32,34,36,42]. Overall, these findings demonstrate that parents experienced stress during the hospitalization of their newborns in the NICU (ES, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.27–0.47; I2=94.1%; P<0.001) (Fig. 4).

Prevalence of stress among parents of newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit. CI, confidence interval; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Among the included studies, the highest and lowest rates of stress among mothers were 76% and 23%, respectively [12,32]. Similarly, the highest and lowest rates of stress among fathers were 0.06% and 35%, respectively (Fig. 4) [21,45].

5. Measurement tools with cutoff scores

Among the 22 studies that assessed the prevalence of anxiety among parents of newborns admitted to the NICU, 13 used the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scale (ES, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.39–0.60; I2=95.3%; P<0.001) [9,11,15,20,24,31,33,34,38,40,41]. Three studies used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (ES, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.11–0.80; I2=98.6%; P<0.001) [28- 30,44]. Two studies used Beck’s Anxiety Inventory scale (ES, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.04–1.25; I2=98.9%; P<0.001) [10,19]. Two studies used the Hamilton Anxiety Rating scale (ES, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.26-0.58; I2=90.7%; P<0.001 [14,35]. One study used the Self- Rating Anxiety Scale (Fig. 5) [7].

Subgroup analysis of anxiety scales used by studies included in the meta-analysis. CI, confidence interval; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Among the 11 studies that assessed the prevalence of depression among parents of newborns in the NICU, 4 used the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (ES, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.18–0.52; I2=93.2%; P<0.001) [6,8,37,39], 3 used the Beck’s Depression Inventory scale (ES, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.18–0.52; I2=93.8%; P<0.001) [14,19,35], 2 used the Centre for Epidemiologic Study Depression Scale (ES, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.28–0.52; I2=72.6%; P<0.001) [17,40], and 2 used the Depression, Anxiety and Strs Scale (ES, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.14– 0.25; I2=0.03%; P<0.001 (Fig. 6) [18,43].

Subgroup analysis of depression scales used by studies included in the meta-analysis. CI, confidence interval; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Among the 18 studies that assessed the prevalence of stress among parents of newborns in the NICU, 6 used the Parental Stress Scale (ES, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.46–0.69; I2=92.2%; P<0.001) [8,12,13,16,17,34], 6 used the Perinatal Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Questionnaires (ES, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.31–0.42; I2=46.1%; P<0.001) [22-24,28,36,42], 3 used the Stanford Acute Strs Reaction Questionnaires (ES, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.25–0.39; P<0.001) [24,30,31], and 2 used the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (ES, 0.19; 95% CI, -0.09 to 0.48; I2=95.7%; P<0.001) [25,32] (Fig. 7).

Subgroup analysis of stress scales used by studies included in the meta-analysis. CI, confidence interval; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

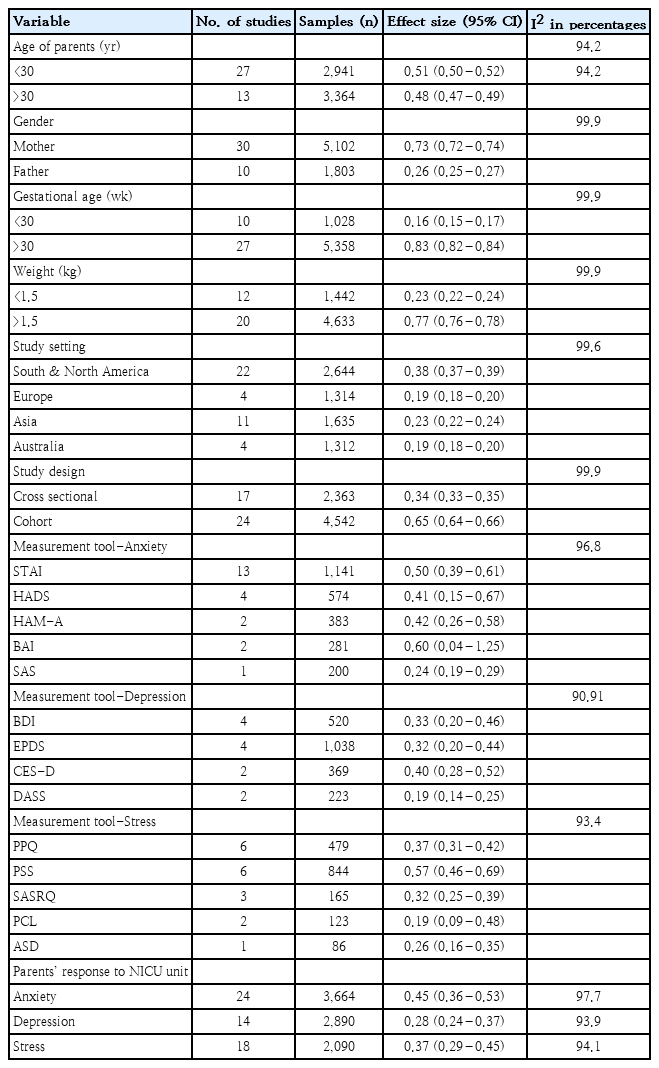

The pooled prevalence of the participants was calculated as 95% CI. The participants were divided into 2 age groups: <30 years (n=2,941) (ES, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.50 to -0.52) and >30 years (n=3,364) (ES, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.47–0.49). Similarly, the majority of participants were mothers (n=5,102) (ES, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.72–0.74) than fathers of newborns (n=1,803) (ES, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.25–0.27). Further, most of the babies were born after 30 weeks’ gestation (n=5,358) (ES, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.82–0.84) and weighed more than 1.5 kg (n=4,633) (ES, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.76–0.78). The existing original studies adopted a cohort (n=4,542) (ES, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.64–0.66) and cross-sectional research design (n=2,363) (ES, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.33–0.35). Twenty-two studies were conducted in South and North America (n=2,644) (ES, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.37–0.39), 11 in Asia (n=1,635) (ES, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.22–0.24), 4 in Europe (n=1,314) (ES, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.18–0.20), and 4 in Australia (n=1,312) (ES, 0.19; 95% CI, 018–0.20). The pooled prevalence of anxiety, depression, stress, and measurement tools is summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis to report the pooled prevalence of anxiety, depression, and stress among parents of neonates in the NICU. Our findings showed that 49% of mothers and 23% of fathers felt anxious when their newborns were admitted to the NICU. Previous studies found similar results: 40% of mothers and 20% of fathers experienced anxiety symptoms during their newborns’ NICU hospitalization.43,46) However, proper counseling and parental involvement during hospitalization improved parental satisfaction [45].

Depression is another major issue among parents of NICU patients. Our meta-analysis revealed that 31% of mothers and 12% of fathers experienced depressive symptoms. Although postpartum depression is common among new mothers, parents reported reduced depression symptoms (from 33.3% to 11.7%) by the fourth week of the NICU admission [47].

Similarly, many NICU parents often report high levels of stress from being physically separated from their newborn and the financial burden compared to parents of healthy babies. Our meta-analysis revealed that 41% of mothers and 21% of fathers experienced psychological stress. The NICU intervention modality and parent- centered care significantly reduced parental stress [48]. Newborns are admitted to the NICU for various reasons, including premature birth, low birth weight, infection, and congenital anomalies [49]. Faced with medical challenges, parents struggle to embrace parenthood [50]. This could be attributed to the mother’s feelings about birthing a sick child and being more concerned about their child’s future growth and development [51]. In addition to being away from family, hospitalization significantly increases the clinical symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression among the parents of neonates in the NICU [10,12,15,16,43].

However, there was no significant correlation between neonatal sex and the psychological symptoms experienced by the parents of neonates admitted to the NICU [16]. Social support, family income, and parental education level were significantly negatively correlated with anxiety and depression among mothers of neonates in the NICU [19].

A similar systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated parent-centered communication regarding parental satisfaction during newborn NICU admission. They concluded that good communication and parental support boosted parental satisfaction. Furthermore, our study results urge healthcare workers to provide timely and effective parent-centered counseling for parents of neonates in the NICU. However, identifying the negative factors that reduce the psychological problems experienced by parents of NICU patients remains challenging for healthcare workers. Family-centered instructional interventions can reduce distress symptoms among mothers and fathers of preterm infants to a similar magnitude. Timely counseling of parents may help them better adjust to the hospital environment and enhance their mental wellbeing [39].

The main strength of our review is that it assessed the pooled prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression and included a subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression in NICU mothers and fathers.

Our review has some limitations. The majority of neonates were discharged before 1 month of age. Therefore, the prevalence of psychological symptoms among parents was examined between only the first and fourth weeks of hospitalization. Second, most of the studies were conducted in high-income countries. Therefore, we could not perform a subgroup analysis of the variations in the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression between low- and high- income countries.

In conclusion, NICU admission can affect parents’ psychological health, which could have a detrimental effect on the parent–child interaction. Parents of neonates in the NICU require counseling, empathy about the neonate’s condition, and encouragement to visit their child in the NICU. More qualitative studies with longitudinal follow-up are needed to address this issue.

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: KH, APS; Data curation:AI, LT; Formal analysis: PM; Methodology: KH, APS, LT; Project administration: VDU, SD; Visualization: VDU, SD, PM; Writing-original draft: APS, KH, AI; Writing-review & editing: SD, RKM, LT