Exploring nutritional screening tools for hospitalized children: a narrative review

Article information

Abstract

Malnutrition is common among hospitalized children, especially those who are critically ill. Routine measures, such as anthropometric measurements, body composition, and nutritional assessment, comprise the basics of monitoring. This review discusses the adequacy of nutritional screening tools (NSTs) such as the SGNA (Subjective Global Nutritional Assessment), PYMS (Pediatric Yorkhill Malnutrition Score), STAMP (Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Paediatrics), and STRONGkids (Screening Tool for Risk of Nutritional Status and Growth). This review included recently published reports supporting the validation and implementation of NSTs in pediatric populations. A child's nutritional status during hospitalization is of great importance for their recovery, while the implementation of screening tools enhances their clinical outcomes. Current tools have varying sensitivities and specificities, and no single tool can be recommended for all groups of hospitalized children. A combination of tools or adaptation of existing tools with validation in different contexts might be ideal. Further studies are required to develop more robust and comprehensive screening tools.

Key message

Malnutrition is frequently identified in hospitalized children, and the use of nutritional screening tools is crucial for assessing their nutritional status during their hospital admission and stay. Common tools include the Pediatric Yorkhill Malnutrition Score, Screening Tool for Assessment of Malnutrition in Pediatrics, and Screening Tool for Risk of Nutritional Status and Growth. However, these tools have varying sensitivities and specificities, and none is recommended for all hospitalized children.

Introduction

Malnutrition is often associated with recovery and outcomes in critically ill children [1]. According to the World Health Organization, malnutrition is defined as a deficiency, excess, or imbalance in food intake and energy requirements. Although the term “undernutrition” is used interchangeably with “malnutrition,” the latter comprises 3 groups: undernutrition, micronutrient-related malnutrition, and overnutrition [2]. The prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized children varies widely, and different studies reported a prevalence rate of 13.4% in developed countries versus 83.5% in African countries [3-5].

Malnutrition is often underreported in hospitalized children, especially among those admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), who are then subjected to an increased risk of sepsis, impaired immunity, wound healing, and gut immunity [2,3]. Many studies have shown an association between undernutrition at the time of a PICU admission and poor outcomes, particularly mortality, length of stay in the PICU and hospital, mechanical ventilation duration, and hospital-acquired infections [6-8]. Albadi and Bookari [9] conducted a meta-analysis of 10,638 patients from 17 observational studies and reported a slightly higher risk of mortality (risk difference=0.02; P=0.05) in undernourished versus well-nourished children.

The resting energy expenditure of children increases in cases of severe illness, which can be considered a state of rapid catabolism, inflammation, and insulin resistance. Hospitalized children experience a loss of energy, decreased appetite, and low intake of protein and calories due to the disease, preexisting comorbidities, immune dysfunction, malabsorption, and administration of drugs, all of which lead to the development of nutritional deficiency. Adequate nutrition is required for energy consumption at rest, during activity, according to disease severity, and for macronutrient metabolism [2,3,5].

According to most studies, nutritional status and outcomes are correlated, and 5%–27% of patients’ nutritional statuses deteriorate during hospitalization [10,11]. Nutritional risk is defined as the current nutritional status and risk of deterioration due to increased requirements caused by the metabolic stress of clinical conditions. All major internationally recognized organizations, including the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) [11], American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) [12], and European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) [13], recommend an evaluation of nutritional status at admission to identify at-risk children. Nutritional screening tools (NSTs) aid the identification of malnourished children and those at risk of developing malnutrition during their hospital stay. An early nutritional risk assessment followed by nutritional intervention can improve patient prognosis and decrease malnutrition-derived complications [14].

Many NSTs, such as the Subjective Global Nutritional Assessment (SGNA), Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Paediatrics (STAMP), Pediatric Yorkhill Malnutrition Score (PYMS), and Screening Tool for Risk on Nutritional Status and Growth (STRONGkids), have been validated for screening in hospital settings [15-21], but no single tool is suitable for all populations since they have different methods, sensitivities, specificities, reliabilities, and validities for detecting malnutrition [22]. This review aimed to summarize the evidence on the application of NSTs to identify nutritional risk in hospitalized children and analyze the development, implementation, validation, and suitability of each.

Methods

A literature search was performed of the PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library databases for studies on NSTs in critically ill children published from inception to February 15, 2025. The following keywords were utilized: "nutritional screening,” "critical illness,” "children,” "malnutrition,” "nutrition assessment,” and "pediatric.”

Studies discussing the development, validation, or implementation of nutritional assessment tools in hospitalized pediatric populations were retrieved and analyzed. Comparative studies including original articles, systematic reviews (SRs), and meta-analyses providing insights into the performance, effectiveness, and impact of NSTs were included. Studies that recruited only adults and whose articles were not written in English were excluded.

Discussion

1. Nutritional screening vs. nutritional assessment

The terms "nutritional screening" and "nutritional assessment" are often used interchangeably because of their blurry demarcations. A nutritional screening is used to indicate the risk factors for a condition leading to nutritional deprivation, whereas a nutritional assessment provides a nutritional diagnosis to enable the planning of appropriate interventions. According to most guidelines, both tests should be routinely performed at hospital admission to identify children at risk of malnutrition and prevent further nutritional decline through appropriate management. However, these methods are not routinely employed in most settings worldwide, other than research settings. Many of these tools are complex, lengthy, and lack sufficient evidence for their implementation in clinical practice. Moreover, societies define these terms differently, increasing confusion among clinicians [14].

The ASPEN defines nutritional screening as “a process for identifying patients who are already malnourished or at risk of malnutrition." [23] According to the ESPEN, screening is a rapid and simple process that can be performed by healthcare workers in hospitals or community settings [24]. In contrast, a nutritional assessment identifies problems and enables specific diagnoses. It involves the continued collection of more information and physical examinations focused on nutrition-related issues to identify nutritional problems and determine their severity. According to the ESPEN, an expert clinician, dietitian, or nutrition nurse should conduct a nutritional assessment [14].

A nutritional screening considers only recent changes in the patient's nutrient intake, weight, and general appearance. However, it does not include a detailed history, a physical examination, or laboratory investigations. In contrast, a nutritional assessment gathers detailed information on the adequacy, degree, and impact of changes in nutrient intake in the following 5 aspects: (1) anthropometric assessment (such as body mass index [BMI], midupper arm circumference, height-for-weight, and standard percentile growth charts); (2) a thorough history of present and past illnesses, surgeries, or medications; (3) a nutrition-focused physical examination; (4) relevant laboratory investigations (to check metabolic and immunity status); and (5) food history and recent dietary changes [14].

A nutritional assessment, along with a nutritional screening, facilitate the customization of pharmacological and surgical interventions and provides a rough idea of a patient's disease recovery, hospitalization needs, and survival chances.

2. Overview of nutritional assessment tools

Numerous NSTs have been developed and validated for hospitalized children and adolescents and used in different settings. A recent SR conducted by Ventura et al. [25] identified 19 NSTs used in hospitalized children. Of them, NSTs in 13 studies could identify nutritional status deterioration and 5 studies included PICU patients, but these were not validated for critically ill children. Thus, consensus is lacking regarding the most suitable NST for pediatric patients. An SR by Pereira et al. [26] identified 10 NSTs for pediatric use, of which the STAMP, PYMS, and STRONGkids were the most frequently used. Other NSTs include the SGNA, Nutrition Evaluation Screening Tool (NEST), and Pediatric Nutrition Screening Tool (PNST). Another SR by Klanjsek et al. [27] identified 8 validated NSTs and 3 nutritional assessment tools for children admitted to the hospital.

The commonly used and validated tools for various setups for children admitted to medical and surgical departments include the STAMP, PYMS, STRONGkids, and PNST. Some commonly used assessment tools for specific diseases include the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) and SGNA for patients in the surgical department, nutrition screening tool for childhood cancer, nutrition screening tool for pediatric patients with cystic fibrosis, Neonatal Nutrition Screening Tool used in the neonatal intensive care unit, and the Clinical Assessment of Nutritional Status score to differentiate malnourished from appropriately nourished babies [25-27]. Other new, less commonly used, or nonvalidated NSTs include the Electronic Health Record – Screening Tool for the Assessment of Malnutrition in Paediatrics (EHR-STAMP, a modified STAMP tool), iNfant Early Nutrition Warning Score, the Lao Nutritional Risk Screen Tool (a modified STRONGkids tool), Nutritional Risk Score (NRS), NST, Pediatric Digital Scaled Malnutrition Risk Screening Tool, Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment, Paediatric Malnutrition Screening Tool (a modified STAMP tool), and Pediatric Nutritional Screening Score [25-27].

NSTs are useful in clinical practice for the early identification of malnourished patients or those at risk of malnutrition. The choice of an NST depends on the healthcare setting, expertise, and resources. It should be easy to use, standardize, validated, less time-consuming, and economical, while its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility should be reasonably high. The NST is initially applied within the first 24–48 hours of admission to detect malnutrition and then repeated regularly to identify nutritional deterioration during the hospitalization. Any NST must consider inadequate nutrition, involuntary weight loss, the patient’s functional capacity, and disease-associated metabolic stress [28,29]. The STAMP is a frequently used tool that can be easily used by clinical dieticians and physicians in both hospitals and clinics. The PYMS is another commonly used tool, mainly designed for hospitalized patients, but it can also be applied in orphanages, charities, and pediatric homes, settings where many children need monitoring, especially in cases of contagious diseases. The STAMP is an excellent tool for ensuring a prompt nutritional risk assessment, whereas the PYMS is suitable for monitoring progress.

3. Important NSTs

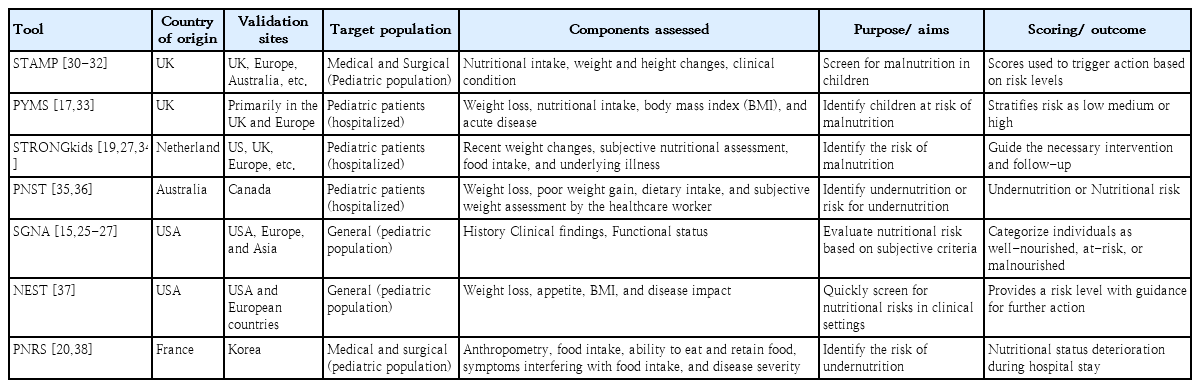

A summary of the important NSTs used in the pediatric population is provided in Table 1 and Supplementary material.

1) Screening tool for assessing malnutrition in pediatrics

The STAMP is a five-step screening tool for measuring the nutritional status of children aged 2–16 years during hospitalization. This tool was designed by a team from the Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital and the University of Ulster [30]. It is easy to use, features good sensitivity (75%–90%), and does not require formal nutrition training; therefore, it can be used by any healthcare worker. This feature makes it a widely used tool to screen for malnutrition among pediatric inpatients. The tool focuses on nutritional intake, weight and height changes, and clinical conditions to assign risk levels and guide clinical action, making it both practical and actionable [16,30]. Several studies have validated the STAMP tool and highlighted its ability to identify children at risk of malnutrition and trigger appropriate nutritional interventions. Wong et al. [31] reported that the STAMP had good agreement with a dietician’s assessment (Cohen kappa value, κ=0.5) and good agreement with the PYMS (κ=0.314), sensitivity of 83.3%, and specificity of 66.7%, proving that it is both valid and reliable for use in hospital admission cases. The same conclusion was reflected in a study by Rub et al. [32] in which the STAMP had a sensitivity of 83.3% and specificity of 82.05%. The STAMP is a good tool for mass screening and outdoor assessment rather than the progressive monitoring of a child’s health. However, its reliance on clinical judgement, nutrient intake, and anthropometric data may limit its applicability for detecting chronic malnutrition in resource-constrained settings [30-32].

2) Pediatric Yorkhill Malnutrition Score

The PYMS, developed by Gerasimidis et al. [17], is a modification of the ESPEN assessment. It was specifically designed for hospitalized pediatric patients and incorporates components such as weight loss, nutritional intake, BMI, and the presence of acute disease. Those children scoring a total of ≥2 should be referred to a dietician for a detailed dietary assessment. Studies have demonstrated that the PYMS is a reliable screening tool for identifying children at risk of malnutrition and stratifying risk into low, medium, or high categories. Gerasimidis et al. conducted a pilot study of critically ill children followed by a larger study in tertiary- and district-level hospitals. The PYMS showed similar sensitivity to the STAMP in a pilot study but much better specificity (95%) and an accurate negative predictive value (92%) when applied in a practical setup [17,33]. Another study reported that PYMS is easy to use and has shown a sensitivity of 65%–85%. The emphasis on recent changes in nutritional status makes it particularly useful for identifying acute risks in clinical care. However, its sensitivity for detecting long-term nutritional issues and chronic malnutrition requires further validation [32,33].

3) Screening tool for risk on nutritional status and growth

The STRONGkids, a simple, easy-to-use, and low-cost questionnaire formulated by Hulst et al. [19], is widely used globally to identify nutritional risks in different populations owing to its good sensitivity and specificity. It should be administered within 48 hours of hospital admission. In the NST, 4 diet- and disease-related items are assigned a score before anthropometric measurements are taken, including recent weight changes, subjective assessment of nutritional status, food intake, and underlying illnesses predisposing an individual to malnutrition. The sum of the scores of the 4 parameters, together with body measurements, identifies the risk of malnutrition classified as high (>4), moderate (1–3), or low (<1) and guides necessary interventions and follow-up [19,27,34].

4) Pediatric Nutrition Screening Tool

The PNST, a simple and rapid assessment tool developed in Australia by White et al. [35] in 2016, negates the need for complicated anthropometric measurements and judicious assessments by a clinical dietician. Physicians, nurses, or dietitians can apply the PNST at 24 hours post-hospital admission to identify children at risk of malnutrition. It consists of 4 questions regarding recent unintentional weight loss, poor weight gain over the last few months, a reduced dietary intake in the past few weeks, and a subjective assessment by the healthcare worker regarding the child being underweight [36]. The child is suffering from malnutrition if 2 or more questions can be answered with a “yes.” According to a study by White et al. [35], this simple tool showed 89.3% sensitivity and 66.2% specificity, establishing its validity and reliability.

5) SGA and SGNA

The SGA has been evaluated as a versatile tool for assessing nutritional risk in the general population. It relies on subjective criteria, including a combination of clinical history, physical findings, and functional status, to determine an individual’s nutritional status. This tool has good sensitivity (>86%) and good reproducibility (κ=0.28) [15]. The SGA effectively categorizes individuals into 3 groups: well-nourished, at-risk, and malnourished. Its simplicity and adaptability make it a practical choice in diverse healthcare settings for detecting malnutrition in children who are moribund, scheduled for surgery, or have postoperative complications or infectious diseases. However, its subjective nature may result in variability among assessors, highlighting the need for adequate training to ensure its consistent application [15,25-27].

In contrast, the SGNA requires more time owing to the use of a more detailed questionnaire to evaluate and classify a patient’s nutritional status. The SGNA considers food intake, gastrointestinal symptoms, anthropometric measurements, functional impairment, physical examination, and metabolic stress of the disease. Finally, nutritional status was categorized as well-nourished, moderately malnourished, or severely malnourished. The SGNA has high false-positive results as standardized height-weight graphs are followed rather than individual yardsticks, causing racial and cultural variations. The SGNA has shown good sensitivity (~80%) and specificity (~75%) and offers a holistic approach; however, it requires a subjective assessment by trained personnel, which might be challenging in resource-limited settings [25-27].

6) Nutrition Evaluation Screening Tool

The NEST model, proposed by Dokal et al. [37], is a quick screening tool applicable to the general population. It evaluates weight loss, appetite changes, BMI, and disease impact. Studies confirmed its effectiveness at efficiently identifying nutritional risks in clinical settings since it showed moderate agreement with 2 tools, the STRONGkids (κ=0.472) and STAMP (κ=0.416), for patients during initial screenings at admission, along with an 87.2% sensitivity rate. The NEST provides a clear risk level with recommendations for further action, making it suitable for rapid assessments. Its utility in both inpatient and outpatient settings has been noted, although its application in specialized populations such as pediatric or critically ill patients requires further study [37].

7) Pediatric Nutritional Risk Score

The Pediatric NRS (PNRS) was developed in France to identify children >1 month of age who are at risk of acute malnutrition during hospitalization. Treating physicians or nurses administer it within 48 hours of admission to evaluate nutritional risk factors. This tool considers anthropometric measurements, the patient's ability to eat, food intake, pain or other symptoms interfering with their food intake, the ability to retain food despite vomiting and diarrhea, and disease severity. Another advantage of the PNRS is that it compares individual standards rather than preexisting charts that evaluate patients individually. The range is 0–5, and nutritional risk is categorized as low (0 points), moderate (1–2 points), or high (3–5 points) [20,38].

4. Validation and comparison of screening tools

The most commonly used NSTs (the STAMP, PYMS, STRONGkids, PNST, and SGNA) have been validated in pediatric populations [27]. These NSTs were validated using reference standards, including anthropometric measurements (weight-for-height z score [WHZ], BMI for age z score, length/height for age z score, midupper arm circumference), nutrition-related biochemical markers, and a dietary intake assessment. These are used in most validation studies because they are common indicators for detecting malnutrition in pediatric patients [39]. Sayed et al. [39] analyzed the sensitivity and specificity of commonly used NSTs (the STAMP, PYMS, STRONGkids, and SGNA) in 1,000 children aged 1–12 years visiting an outpatient clinic, using anthropometric measurements (weight, length/height, and weight for length/height) as the gold standard. The highest sensitivity (79.4%) and specificity (80.2%) were found for the STRONGkids, followed by the SGNA and STAMP, which had sensitivities of 77.5% and 73.5%, respectively, and specificities of 81.4% and 93.5%, respectively. The PYMS demonstrated the lowest sensitivity (66.7%) and highest specificity (93.5%).

Malekiantaghi et al. [40] compared the efficacies of 3 NSTs (the STAMP, PYMS, and STRONGkids) at identifying the risk of malnutrition in hospitalized children using the WHZ and BMI Z-scores. They found a significant relationship between the PYMS and WHZ (P<0.001), BMI z score (P<0.001), and STRONGkids and WHZ scores (P=0.017). Teixeira and Viana [41] conducted an SR to study the diagnostic accuracy of these NSTs in hospitalized children. They reported high sensitivity of the STAMP with almost perfect interrater agreement with the reference standard, whereas the STRONGkids had high sensitivity, low specificity, substantial intrarater agreement, and ease of use. Dos Santos et al. [42] reported that the STRONGkids is a valid, easy-to-use, and reproducible tool with good inter-and intrarater agreements.

5. NST in PICU settings

Malnutrition in PICU patients has a variable prevalence that ranges from 13.4% in developed countries to 83.5% in African countries at the time of admission [3]. In addition to the risk of undernutrition, patients in the PICU have increased nutrient requirements owing to a surge in metabolic stress and inflammation. The nutritional status of these patients can deteriorate dramatically because of malabsorption and feeding intolerance [6,9]. Ventura et al. [25] conducted an SR that identified 19 NSTs in the pediatric population. Only 5 of these NSTs are applied to critically ill patients: PYMS, STRONGkids, PICU-SGNA, Hospital Malnutrition Risk Assessment Tool, and Mezoff’s NRS. However, to date, none of these have been validated in PICU settings. Furthermore, none of these NSTs assessed illness severity, which is an important and relevant variable in PICU patients.

The PICU-SGNA can potentially be considered an NST tool for critically ill children. However, it is neither a rapid nor simple screening tool in the PICU population since it requires a detailed assessment [43]. Recently, dietitians at Children’s Wisconsin Hospital developed a unique tool, the Children’s Wisconsin Nutrition Screening Tool (CWNST), which is embedded within electronic medical records and has increased sensitivity compared with the PNST. The CWNST had a sensitivity of 0.985 and specificity of 0.06, whereas the PNST alone had a sensitivity of 0.1 and specificity of 0.981. The CWNST can be easily applied through emergency medical records to predict the nutritional risk of PICU patients. However, refinement is needed to enhance the specificity for identifying at-risk PICU patients who may benefit from early nutritional intervention [44].

6. Challenges and opportunities using NSTs

One of the major challenges of a comprehensive NST is the lack of standardization in its use. Despite extensive research, its implementation remains far from practical. These NSTs were evaluated in the general population of hospitalized children; therefore, further validation is needed in different groups, such as children attending outpatient clinics, those with cancers and complex chronic conditions, and those admitted to the PICU. In addition, most validation studies have been conducted in developed countries, and the use of these NSTs is limited in underdeveloped countries owing to a lack of resources despite having a higher burden of malnutrition.

Although several NSTs have been developed and validated for hospitalized children and adolescents, consensus is lacking on the most suitable NST for pediatric use, and many studies have reported poor sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy. Chourdakis et al. [45] evaluated 3 NSTs (the PYMS, STAMP, and STRONGKIDS) and compared them with the anthropometric measurements, clinical variables, and body composition of 2,567 hospitalized children across 12 European countries. They reported the failure of all 3 tools at identifying children with subnormal anthropometric measurements and did not recommend any of the 3 NSTs for use in clinical practice. Lee et al. [38] evaluated 4 NSTs (the PNRS, STAMP, PYMS, and STRONGkids) in hospitalized Korean children with anthropometric and clinical variables and found considerably different results with 4 NSTs to screen nutrition risks at admission. Huysentruyt et al. [46] conducted an SR to evaluate the accuracy of various NSTs for assessing nutritional risk in hospitalized children in developed countries; they also failed to show any preference for choosing any one tool over another based on accuracy. Ventura et al. [25] found that none of the 19 NSTs used in hospitalized children were validated for identifying malnutrition in children admitted to the PICU. A new tool, the EHR-STAMP, was developed to incorporate the electronic health record and was deemed an easy-to-use, electronic health record–compatible, and reliable tool for screening nutritional risk in hospitalized children [47].

Despite the recognized importance of nutritional assessments, significant challenges remain in the field. Healthcare workers must understand the value of assessing patients’ nutritional statuses, applying tools to detect undernutrition, and ensuring appropriate care and referral. Major challenges for NSTs include a lack of expertise, differences in clinical opinions, and abnormal built comparisons. Addressing these challenges requires the development of robust and comprehensive nutritional assessment tools tailored to the unique needs of critically ill children. Future research should consider ways to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms of malnutrition, validate assessment tools in diverse clinical settings, and evaluate the effects of precise nutritional interventions on clinical outcomes. Although we reviewed the common tools, their scoring systems, uses, strengths, and weaknesses, a more detailed discussion focusing on criteria such as endocrine imbalance (gigantic or dwarf), children with subnormal physique, or specific PICU admission cases can provide better insight to clinicians.

Conclusion

Integrating nutritional assessments into routine clinical practice in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team can facilitate the early detection of and prompt intervention for malnutrition, thereby preventing adverse outcomes in this vulnerable patient population. Current evidence suggests that no single tool provides perfect sensitivity and specificity owing to unique socioeconomic and nutritional challenges. A combination of tools or adaptation of existing tools with validation in different contexts might be ideal. Incorporating cultural and dietary specifics into assessment tools is critical to improving their applicability and accuracy.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at https://doi.org/10.3345/cep.2025.00633.

Various nutritional screening tools used in pediatric patients

Notes

Conflicts of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: AA; Data curation: PS, GJ; Formal analysis: AA; Methodology: PS, AA, GJ; Writing - original draft: PS; Writing - review & editing: AA, GJ