All issues > Volume 53(10); 2010

A case of intracranial hemorrhage in a neonate with congenital factor VII deficiency

- Corresponding author: Young Sil Park, M.D. Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University School of Medicine, East-West Neo-medical Center, 149 Sangil-dong, Kangdong-gu, Seoul, 134-727, Korea. Tel: +82.2-440-7173, Fax: + 82.2-440-7175, pysmd@khnmc.or.kr

- Received August 13, 2010 Revised September 13, 2010 Accepted September 30, 2010

- Abstract

-

Congenital factor VII deficiency is a rare autosomal-recessive bleeding disorder. Bleeding manifestations and clinical findings vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic subjects to patients with hemorrhages that may cause significant handicaps. Treatment has traditionally involved factor VII(FVII) replacement therapy using fresh frozen plasma, prothrombin complex concentrates or plasma-derived FVII concentrates. Recombinant activated FVII (NovoSeven®) is currently considered the first-line treatment for replacement therapy of FVII deficiency. Here we present a case of severe intracerebral and intraventricular hemorrhage in a neonate with congenital FVII deficiency.

- Introduction

- Introduction

Factor VII (FVII) is a vitamin K-dependent clotting factor that is part of the extrinsic pathway of blood coagulation1). The complex formed between the naturally occurring procoagulant serine protease, activated FVII (FVIIa), and the integral membrane protein tissue factor (TF), exposed on the vascular lumen upon injury, is known to be the trigger for blood clotting. In the blood stream, FVIIa is the active portion of the FVII mass and is detectable at normal concentrations as low as 5-10 ng, i.e., 1-2% of the zymogen; in contrast to FVII zymogen, FVIIa has a very high affinity for TF1, 2).Congenital FVII deficiency is a rare bleeding disorder. In patients with congenital FVII deficiency, bleeding manifestations and clinical findings vary widely, ranging from asymptomatic subjects to life threatening bleeding1, 3). However, severe and life-threatening hemorrhaging is rare in general (about 5% of the bleeds) and occurs most frequently during the first six months of life. The correlation between FVII coagulation activity (FVII:C) and bleeding tendency appears to be poor4, 5). Treatment has traditionally involved FVII replacement therapy using fresh frozen plasma, prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) or plasma FVII concentrates2, 3). Intravenous administration of recombinant FVIIa (NovoSeven®, NovoNordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) is now widely used for the treatment of FVII deficiency. Here we present a case of severe intracerebral and intraventricular hemorrhage in a neonate with congenital FVII deficiency.

- Case report

- Case report

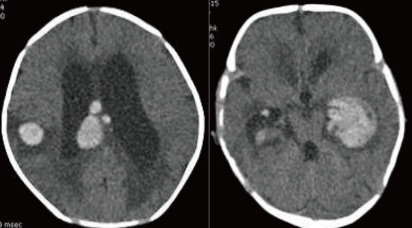

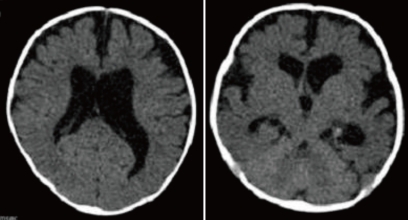

A 28-day-old male neonate was referred with fever for five days and sudden progress of anemia, suggestive of an intracranial hemorrhage (ICH). He was born to a 35-year-old gravida 1, para 1 mother at 39+6 weeks of gestation via cesarean delivery without any perinatal problems. His birth weight was 3,000 g. There was no significant family history about any bleeding disorder. At the time of transfer, the pulse rate was 150 beats/min, respiratory rate was 42 breaths/min, blood pressure was 80/50 mmHg and body temperature was 37.3℃. Physical examination revealed pallor, anemic conjunctivae, and a minimal systolic murmur. The head circumference was 38 cm (50-75 percentile) and there were no abnormalities on the neurological examination. Laboratory findings were as follows: hemoglobin of 6.5 g/dL; white blood cell (WBC) count of 17,500/mm3; and a platelet count of 387,000/mm3. CRP was 1.03 mg/dL (normal range: 0.0-0.5). The blood coagulation test revealed a prothrombin time 34.8 seconds (INR 3.65) and activated partial thromboplastin time of 34.2 seconds. The FVII assay was 2%. Brain computed tomography (CT) demonstrated an intraventricular hemorrhage in both lateral ventricles with hydrocephalus and an intracerebral hemorrhage in the right parietotemporal lobe and corpus callosum (Fig. 1). On admission, recombinant activated FVII (Novoseven®, Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) was administrated at a dose of 20 µg/kg every 4 hours. To treat the hydrocephalus, external ventricular drainage was considered; however, the risk of bleeding was a concern. Therefore, periodic lumbar puncture and drainage were performed and mannitol was administered. First lumbar puncture was done at hospital day 3 and performed every 3-4 days after Novoseven® was administrated. Results of CSF study were as follows: Red blood cell count of 23,000/mm3, WBC count of 77/mm3; glucose of 18 mg/dL, protein of 223.0 mg/dL. The FVII level was checked 1 hr after administration of the Novoseven® and was confirmed to be 125%. The interval between dosing with Novoseven® was increased to seven days after admission. The fever persisted until seven days after admission, and then, finally subsided. Blood, urine, CSF, and stool culture were unremarkable. The patient was treated with a third generation cephalosporin. The brain CT at seven days after admission revealed decreased IVH in both lateral ventricles and slight resolution of the ICH with perilesional edema. Administration of the FVII was continued for 20 days during the hospitalization. The patient was discharged 21 days after admission. A follow-up CT of the brain at 1 month showed a resolving ICH, decreased IVH and slightly improved hydrocephalus (Fig. 2). At present, the patient is on no medication and is followed in the outpatient clinic regularly. The development currently is within normal limits. A follow-up CT scan of the brain and developmental testing are planned.

- Discussion

- Discussion

Congenital FVII deficiency is a rare autosomal recessive bleeding disorder that has an estimated incidence of 1/500,000 among the general population6). There are 20 known patients with congenital FVII deficiency in Korea7). And, neonate with FVII deficiency and ICH has not been reported yet. FVII plays a pivotal role in the initiation of hemostasis and coagulation. Binding of FVII to TF in the damaged vascular bed results in rapid conversion of FVII to FVIIa through the action of proteases1, 8). In turn, FVII plays a key role in the early phases of the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways through activation of factor IX (FIX) and factor X (FX).Nosebleeds are a common symptom. This disorder is not gender-related. Other very common symptoms are postoperative, skin and gum bleeding1, 2). A female gender is more common among bleeders: this is mainly attributable to menorrhagia. Severe and life-threatening hemorrhages are rare in general (about 5% of the bleeds) and occur most frequently during the first six months of life. According to some reports, central nervous system (CNS) bleeding has been identified in 4.4-8%. Severe bleeding, CNS and gastrointestinal bleeding have been reported mainly in babies and infants1, 3, 5).In patients with hemophilia A and B, a reliable classification of severity can be obtained by plasma factor VIII or IX activity levels. Depending on the concentration of FVIII or FIX coagulant activity in the blood, the disorders may be classified as severe (<1% of normal activity). In patients with FVIII or IX concentrations in plasma <1% of normal, joint bleeding episodes may occur as frequently as 20-30 times/year, and life-threatening bleeding such as intracranial hemorrhage may occur9). However, in a study on FVII deficiency, it was reported that patients with FVII:C levels below 2% were either asymptomatic or had a very mild phenotype; by contrast, patients with FVII:C levels above 5%, most had severe symptoms. Even when FVII:C levels are statistically lower in bleeders, it is generally agreed that they do not predict bleeding tendency in an individual patient5, 10).Treatment of congenital FVII deficiency consists of replacement therapy with fresh frozen plasma (FFP), PCCs, FVII concentrates and/or recombinant FVIIa (NovoSeven®)4, 11). As FFP, PCCs and FVII concentrates are plasma-derived products, the use of these products is associated with the risk of transmission of pathogens12). In addition, the use of PCCs results in an unwanted increase in other vitamin-K-dependent factors and is associated with both arterial and venous thrombosis. Recombinant FVIIa has been available on a compassionate and emergency use basis since 1988 for patients with hemophilia with inhibitors to FVIII or FIX, and patients with congenital FVII deficiency4, 12). Intravenous administration of recombinant FVIIa (NovoSeven®) is now widely used for the treatment of FVII deficiency; however, there are no recommended guidelines for the dose and treatment schedule. According to recent reports, the median dose per injection (22 µg/kg) was within the dose range recommended in the protocols for FVII-deficient patients (15-30 µg/kg every 4-6 h until hemostasis was achieved). For more severe bleeding (e.g. central nervous system and internal bleeding episodes) the patients were treated for a longer period of time. Treatment with recombinant FVIIa for CNS bleeding was rated as effective in 11/14 cases4, 11). Cases of ICH with FVII deficiency treated by FFP have been reported13, 14). In the case reported here, recombinant FVIIa was administrated at dose of 20 µg/kg for 20 days, and it was effective.Review of the medical literature revealed that as many as one-third of episodes recorded in the neonatal period had a delayed diagnosis and/or treatment10, 15, 16). Pediatricians should be advised of the need for hemostasis control in newborns with ICH. This should facilitate the early diagnosis of possible hemophilia and appropriate treatment. The frequency and significance of neonatal ICH underscores the importance of the early diagnosis of hemophilia. Moreover, children should be closely followed for several days as symptoms of ICH may be delayed for up to six days in the case of severe hemophilia, and longer for mild hemophilia. For the case reported here, there were no specific signs of an ICH, e.g. persistent vomiting, change of mental status, seizure; the patient had the nonspecific findings of fever and poor feeding. The initial administration of factor replacement was started five days after the fever developed.Prophylactic therapy with factor concentrates is currently the most effective intervention available for the prevention of bleeding episodes in patients with hemophilia. In congenital FVII deficiency, prophylaxis has been a debated issue, especially because of the very brief maintenance of infused FVII in the blood stream17, 18). One report suggests that prophylactic treatment with recombinant FVIIa in patients with FVII deficiency with dosage of 20-30 µg/kg once to twice weekly may be beneficial in preventing hemorrhagic complications in spite of the short plasma half life17). However, this remains a controversial issue.In summary, congenital FVII deficiency is a rare inherited bleeding disorder. Clinical heterogeneity is the hallmark of this hemorrhagic disorder; the severity ranges from lethal to mild, and there are asymptomatic forms. Here, a case of FVII deficiency and severe ICH with successful management using recombinant FVIIa is reported.

- References

- 1. Mariani G, Colce A. In: Lee CA, Berntorp EE, Hoots WK,Congenital factor VII deficiency. editors. Textbook of Hemophilia. 20102nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, :341–347.3. Lapecorella M, Mariani G. International Registry on Congenital Factor VII Deficiency. Factor VII deficiency: defining the clinical picture and optimizing therapeutic options. Haemophilia 2008;14:1170–1175.

[Article] [PubMed]4. Mariani G, Konkle BA, Ingerslev J. Congenital factor VII deficiency: therapy with recombinant activated factor VII - a critical appraisal. Haemophilia 2006;12:19–27.

[Article] [PubMed]5. Mariani G, Dolce A, Marchetti G, Bernardi F. Clinical picture and management of congenital factor VII deficiency. Haemophilia 2004;10(Suppl 4): 180–183.

[Article] [PubMed]6. Mannucci PM, Duga S, Peyvandi F. Recessively inherited coagulation disorders. Blood 2004;104:1243–1252.

[Article] [PubMed]7. Korea hemophilia foundation. 2009 Annual report. 2010;Seoul: KHF, :30–34.8. Hoffman M, Monroe DM 3rd. A cell-based model of hemostasis. Thromb Haemost 2001;85:958–965.

[Article] [PubMed]9. van den Berg HM, Fischer K. In: Lee CA, Berntorp EE, Hoots WK,Phenotypic-genotypic relationship. editors. Textbook of hemophilia. 20102nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, :33–37.10. Mariani G, Herrmann FH, Dolce A, Batorova A, Etro D, Peyvandi F, et al. International Factor VII Deficiency Study Group. Clinical phenotypes and factor VII genotype in congenital factor VII deficiency. Thromb Haemost 2005;93:481–487.

[Article] [PubMed]11. Brenner B, Wiis J. Experience with recombinant-activated factor VII in 30 patients with congenital factor VII deficiency. Hematology 2007;12:55–62.

[Article] [PubMed]12. Mariani G, Bernardi F. Factor VII Deficiency. Semin Thromb Hemost 2009;35:400–406.

[Article] [PubMed]13. Kim MK, Shin SJ, Kim KO, Lee KH, Hyun MS, Cho HS. A case of congenital factor VII deficiency presented with subacute subdural hematoma. Yeungnam Univ J Med 2004;21:231–236.

[Article]14. Kim HJ, Jung JH, Lee JH, Jo JD. A case of congenital Factor VII deficiency associated with intraventricular hemorrhage and hydrocephalus. J Korean Pediatr Soc 1998;41:1726–1730.15. Antunes SV, Vicari P, Cavalheiro S, Bordin JO. Intracranial haemorrhage among a population of haemophilic patients in Brazil. Haemophilia 2003;9:573–577.

[Article] [PubMed]16. Stieltjes N, Calvez T, Demiguel V, Torchet MF, Briquel ME, Fressinaud E, et al. French ICH Study Group. Intracranial haemorrhages in French haemophilia patients (1991-2001): clinical presentation, management and prognosis factors for death. Haemophilia 2005;11:452–458.

[Article] [PubMed]

About

About Browse articles

Browse articles For contributors

For contributors