All issues > Volume 54(9); 2011

Short term outcomes of topiramate monotherapy as a first-line treatment in newly diagnosed West syndrome

- Corresponding author: Sajun Chung, MD. Department of Pediatrics, Kyung Hee University Medical Center, 1 Hoegi-dong, Dongdaemun-gu, Seoul 130-702, Korea. Tel: +82-2-958-8301, Fax: +82-2-958-8845, sajchung@khmc.or.kr

- Received June 22, 2011 Revised August 04, 2011 Accepted August 31, 2011

- Abstract

-

- Purpose

- Purpose

- To investigate the efficacy of topiramate monotherapy in West syndrome prospectively.

- Methods

- Methods

- The study population included 28 patients (15 male and 13 female children aged 2 to 18 months) diagnosed with West syndrome. After a 2-week baseline period for documentation of the frequency of spasms, topiramate was initiated at 2 mg/kg/day. The dose was increased by 2 mg/kg every week to a maximum of 12 mg/kg/day. Clinical assessment was based on the parents' report and a neurological examination every 2 weeks for the first 2 months of treatment. The baseline electroencephalograms (EEGs) were compared with the post-treatment EEGs at 2 weeks and 1 month.

- Results

- Results

- West syndrome was considered to be cryptogenic in 7 of the 28 patients and symptomatic in 21 patients. After treatment, 11 patients (39%) became spasm-free, 6 (21%) had more than 50% spasmsreduction, 3 (11%) showed less than 50% reduction, and 8 (29%) did not respond. The effective daily dose for achieving more than 50% reduction in spasm frequency, including becoming spasm-free, was found to be 5.8±1.1 mg/kg/day. Nine patients (32%) showed complete disappearance of spasms and hypsarrhythmia, and 11 (39%) showed improved EEG results. Despite adverse events (4 instances of irritability, 3 of drowsiness, and 1 of decreased feeding), no patients discontinued the medication.

- Conclusion

- Conclusion

- Topiramate monotherapy seems to be effective and well tolerated as a first line therapy for West syndrome and is not associated with serious adverse effects.

- Introduction

- Introduction

West syndrome is an age-related epilepsy syndrome that includes the triad of infantile spasms, an inter-ictal electroencephalographic (EEG) pattern called hypsarrhythmia, and mental retardation. West syndrome is believed to reflect abnormal interactions between the cortex and brainstem structures1,2). The frequent onset of West syndrome in infancy suggests that an immature central nervous system may have an important role in its pathogenesis. The brain-adrenal axis also may be involved3). One theory holds that the effect of different stressors in the immature brain produces an abnormal excessive secretion of corticotrophin-releasing hormone, causing spasms4). The clinical response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and glucocorticoids can be explained by suppression of corticotrophin-releasing hormone production. For this reason, ACTH and glucocorticoids were widely used for the management of West syndrome as the first-line therapy for many decades5). The efficacy of ACTH for resolution of West syndrome has varied from as low as 33% to as high as 100%6,7). These patients may have, however, significant and potentially fatal adverse effects; electrolyte imbalance, hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and secondary infection8-10). Some previous controlled studies support vigabatrin as a first line therapy, but visual field defect which is a possible adverse effect of this drug may limit its use11,12).Recently, many researches are reported in order to treat West syndrome effectively with avoiding harmful adverse effects of existing drugs. Topiramate (TPM) is the one of new antiepileptic drugs which has been studied for this purpose. TPM has multiple mechanisms of action, including state-dependent inhibition of sodium channels, potentiation of r-aminobutyric acid-induced chloride influx, blockade of glutamate related excitatory neurotransmission, and inhibition of carbonic anhydrase13). Thus, TPM exerts beneficial effects on several seizure types, including those that are resistant to older antiepileptic drugs.For the management of West syndrome, TPM has been used as an add-on therapy to first-line drugs in most studies14-16). Other studies have treated patients with multiple antiepileptic drugs concurrently with TPM17). But only a few studies suggested that TPM can be a first-line drug and can be used as monotherapy18,19). The aim of our study was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of TPM monotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed West syndrome.

- Materials and methods

- Materials and methods

- 1. Patients

- 1. Patients

A total of 28 patients with newly diagnosed West syndrome who had agreed to get TPM monotherapy between March 2007 and February 2009 were included. Subjects were required to exhibit an average of more than one cluster of spasms per day over a 2-week baseline period before TPM therapy. The following criteria were used to establish the diagnosis of West syndrome: 1) clinical seizures consistent with infantile spasms, and 2) EEG findings demonstrating hypsarrhythmia, modified hypsarrhythmia, and suppression-burst. To ensure that we obtained informed consents from the patients' parents, we provided them with detailed information about the standard treatment options for West syndrome, and the efficacy and potential side effects of TPM. Additionally, we educated them about keeping daily diaries of the occurrences of the spasms.- 2. Topiramate treatment

- 2. Topiramate treatment

After a 2-week baseline period for documentation of frequency of spasms, TPM was started at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day. The dosage was increased by 2 mg/kg increments every week until spasms disappeared or a maximal dose of 12 mg/kg/day was achieved.- 3. Measurement of outcomes

- 3. Measurement of outcomes

At 2 months after the initiation of TPM monotherapy, we analyzed all patients to measure the effectiveness and tolerability of TPM. The primary efficacy measure was a comparison of frequencies of spasms between the 2 weeks of the baseline period and the first 2 months of treatment with TPM. We also compared baseline EEGs with posttreatment EEGs done at 2 weeks and 1 month after initiation of treatment. We monitored clinical progress every 2 weeks for the first 2 months of treatment. At each visit, frequency of spasms was recorded, and complete physical and neurologic examinations were performed. We also obtained routine laboratory data, including blood cell counts, electrolyte analysis, urinalysis, and liver and renal function tests. After the first 2 months of treatment, a routine follow up schedule for each patient was offered. At each visit, adverse effects were also monitored with patients' statement and results of examination.- 4. Statistical analysis

- 4. Statistical analysis

The statistical tool we used was the SPSS ver. 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Mann-Whitney U test was done and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

- Results

- Results

- 1. Patient characteristics

- 1. Patient characteristics

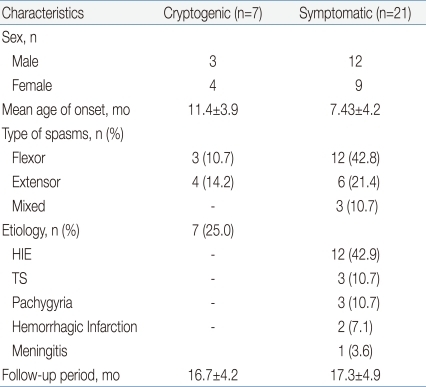

This study included 15 male and 13 female subjects between 2 and 18 months of age. The median age for spasm onset was 8.4 months. Flexor spasms were the most common type of spasm. Regarding etiologic factors, 7 of 28 patients (25%) had cryptogenic epilepsy and the other 21 (75%) had symptomatic causes including hypoxicischemic encephalopathy, tuberous sclerosis, pachygyria, hemorrhagic infarction and meningitis (Table 1). The average follow up period was 17.2±4.7 weeks.- 2. Outcomes

- 2. Outcomes

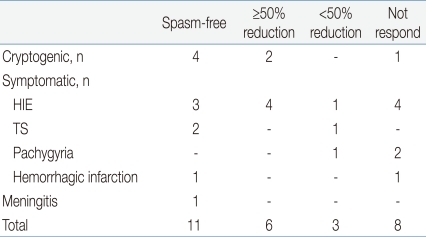

Overall, 11 of 28 patients (39%) had cessation of spasms at TPM doses ranging from 5 to 8 mg/kg/day. A total of 17 patients (61%), including 11 spasms-free patients, achieved ≥50% reduction in frequency of spasms compared to baseline. Regarding the etiologies of West syndrome, 4 of 7 cryptogenic patients (57%) and 7 of 21 symptomatic patients (33%) became free of spasms with TPM monotherapies (Table 2). The mean doses of TPM during stabilization were 5.5±0.9 mg/kg/day in a spasms-free group and 6.3±1.2 mg/kg/day in a ≥50% spasms-reduction group. In a non responder group, the mean doses of TPM were 8.0±2.2 mg/kg/day (ranges from 5 to 12 mg/kg/day), which was somewhat higher than the responder group, but showed no statistical significance. On follow up EEGs, 9 of 28 patients (32%) showed cessation of spasms and hypsarrhythmia, and 11 (39%) showed improved EEGs. With regard to the outcomes, 7 of 11 spasms-free patients showed normal EEGs and 4 showed improved EEGs. In a ≥50% spasms-reduction group, the EEGs were normal in one patient, improved in 3, and not changed in 2 (Table 3).- 3. Adverse effects of topiramate

- 3. Adverse effects of topiramate

Eight of 28 patients (29%) exhibited adverse effects during titration, stabilization or both. The most common side effect was irritability. Other adverse effects included excessive drowsiness and decreased feeding. None of the patients discontinued from TPM because of side effects.

- Discussion

- Discussion

West syndrome is one of the catastrophic epileptic syndromes of infancy and is commonly associated with poor long-term outcomes, development of other seizure types, and impaired cognitive and psychosocial functioning. Despite the clinical significance of West syndrome, complete remission of spasms is difficult to achieve and the optimal treatment remains uncertain. To date, many drugs have been tried to control seizures and were proposed as first-line therapy for West syndrome. Since Sorel and Dusaucy-Bauloye20) reported the efficacy of ACTH treatment for West syndrome, ACTH has been used as the drug of choice for many decades21). In several randomized controlled trials, ACTH was effective for the short-term treatment of West syndrome and in the resolution of hypsarrhythmia. The cessation or reduction of spasms was reported in 42 to 87% of patients who had ACTH therapy and the relapse rate varied from 15 to 36% of responders5). However ACTH therapy also has problems which include the inconvenience of administration, daily intramuscular injection and increased risk of severe adverse events such as electrolyte imbalance, hypertension, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and secondary infection8-10).TPM is a newer antiepileptic drug that has been widely used for control of partial and generalized tonic-clonic seizures in adults22,23). In children, TPM is used as adjunctive treatment for partial-onset seizures24) and for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Sachdeo et al.25) reported that TPM as adjunctive therapy for the management of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome reduced seizure rates by 33%. Recently, a few trials for TPM as a first-line drug for West syndrome have been reported. Glauser et al.14) conducted a pilot study to test the effects of TPM in patients with West syndrome who were refractory to conventional drugs. With high doses (up to 24 mg/kg/day, with a mean dose of 15.0±5.7 mg/kg/day) and rapid titration rates (raising doses every 2 to 3 days), 9 of 11 subjects, including 5 spasms-free patients, achieved a ≥50% reduction of spasms. Using the modified method of Glauser et al.14), Hsieh et al.26) conducted a study of the efficacy of TPM with lower starting doses and a slower titration rate. With a mean dose of 7.4±4.9 mg/kg/day, 11 of 13 subjects, including 5 spasms-free patients, achieved a ≥50% reduction of spasms. These studies suggested that TPM had the similar effects in the treatment of West syndrome compared to other first-line drugs.In most studies on TPM in West syndrome, however, they used TPM as concurrent therapy with other epileptic drugs. Although Kwon et al.18) reported that 14 of 20 patients (70%) were improved (≥50% reduction of spasms after using TPM monotherapy), data on TPM monotherapy in West syndrome are still scarce. We enrolled 28 patients with newly diagnosed West syndrome and evaluated the efficacy of TPM monotherapy. A total 17 patients (61%) including 11 spasms-free patients (39%) achieved a ≥50% reduction of spasms. This result was similar to outcomes of other studies in which TPM had been used as add-on therapy14,26-28) as well as a study of TPM monotherapy18). Although there were diversities in maximal dosages of TPM among each patients who could achieve the optimal outcomes, the lower maximal dose and slower dose titration of TPM were respected to allow the assessment of the patients' responses and increased patient tolerability to the drug29). In our study, TPM was initiated at 2 mg/kg/day and titrated up to a maximal dose of 12 mg/kg/day by 2 mg/kg increments every week. The mean doses of TPM were 5.8±1.1 mg/kg/day in the group having ≥50% reduction of spasms including those who were spasms-free. The mean dosage of TPM applied in our study was relatively low compared with other reports conducted with the low dosages18,26,27) as well as high14). There was a study, however, which concluded that the mean dosage during stabilization was 5.2 mg/kg/day similar to that of our study17). In the other study30), a wide range of TPM dosage (ranges from 1.3 to 35 mg/kg/day) was reported and some patients who responded in 1 month or less did so at very low doses, 1.3 and 3.4 mg/kg/day. These results showed that the optimal dosage of TPM was not determined yet and further studies are required. Hence, we concluded that a low maximal dose and slower titration during TPM monotherapy might be effective as a first-line therapy for West syndrome.It seems that the response rate of TPM in patients with different seizure etiologies is controversial. Although several reports showed that the patients who had cryptogenic etiology responded better to TPM than did the symptomatic patients18,31,32), different results were also reported28,33). In our study, 4 of 7 cryptogenic patients had complete disappearance of spasms and hypsarrhythmia, and 6 of 7 cryptogenic patients (85%) achieved a ≥50% reduction in seizure frequencies. In symptomatic patients, 11 of 21 patients (52%) including 7 spasms-free patients responded. There was no statistical difference between cryptogenic and symptomatic groups (P=0.208). It is presumed that the different results among studies are due to the small number of patients.The reported adverse effects of TPM include central nervous system problems, behavioral and cognitive problems, gastrointestinal effects, weight loss, acute angle-closure glaucoma, oligohydrosis, and kidney stones34-39). These adverse effects can cause a failure or prolongation of treatment in spite of milder problems in severity than those of ACTH. Although 8 of 28 patients in our study exhibited several kinds of adverse effects (e.g., irritability, drowsiness), side effects were not severe to discontinue or reduce the dose of TPM and resolved spontaneously.In conclusion, our results suggest that TPM is both effective and well tolerated as a first-line monotherapy for newly diagnosed West syndrome. We recommend that a low maximal dose of TPM and a slow dose titration are considered to avoid adverse effects. However, our study has limitations such as a small number of subjects and a short follow up period. Further studies will be required to determine long term outcomes of TPM monotherapy including evaluation of relapse rates and delayed side effects.

- References

- 1. Juhász C, Chugani HT, Muzik O, Chugani DC. Neuroradiological assessment of brain structure and function and its implication in the pathogenesis of West syndrome. Brain Dev 2001;23:488–495.

[Article] [PubMed]2. Satoh J, Mizutani T, Morimatsu Y. Neuropathology of the brainstem in age-dependent epileptic encephalopathy--especially of cases with infantile spasms. Brain Dev 1986;8:443–449.

[Article] [PubMed]3. Baram TZ, Mitchell WG, Hanson RA, Snead OC 3rd, Horton EJ. Cerebrospinal fluid corticotropin and cortisol are reduced in infantile spasms. Pediatr Neurol 1995;13:108–110.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]4. Baram TZ, Schultz L. Corticotropin-releasing hormone is a rapid and potent convulsant in the infant rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 1991;61:97–101.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]5. Mackay MT, Weiss SK, Adams-Webber T, Ashwal S, Stephens D, Ballaban-Gill K, et al. Practice parameter: medical treatment of infantile spasms: report of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology 2004;62:1668–1681.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]6. Yanagaki S, Oguni H, Hayashi K, Imai K, Funatuka M, Tanaka T, et al. A comparative study of high-dose and low-dose ACTH therapy for West syndrome. Brain Dev 1999;21:461–467.

[Article] [PubMed]7. Baram TZ, Mitchell WG, Tournay A, Snead OC, Hanson RA, Horton EJ. High-dose corticotropin (ACTH) versus prednisone for infantile spasms: a prospective, randomized, blinded study. Pediatrics 1996;97:375–379.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]8. Bobele GB, Ward KE, Bodensteiner JB. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy during corticotropin therapy for infantile spasms. A clinical and echocardiographic study. Am J Dis Child 1993;147:223–225.

[Article] [PubMed]9. Shamir R, Garty BZ. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia associated with adrenocorticotropic hormone treatment for infantile spasms. Eur J Pediatr 1992;151:867

[Article]10. Riikonen R, Simell O, Jääskeläinen J, Rapola J, Perheentupa J. Disturbed calcium and phosphate homeostasis during treatment with ACTH of infantile spasms. Arch Dis Child 1986;61:671–676.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]11. Appleton RE, Peters AC, Mumford JP, Shaw DE. Randomised, placebo-controlled study of vigabatrin as first-line treatment of infantile spasms. Epilepsia 1999;40:1627–1633.

[Article] [PubMed]12. Vigevano F, Cilio MR. Vigabatrin versus ACTH as first-line treatment for infantile spasms: a randomized, prospective study. Epilepsia 1997;38:1270–1274.

[Article] [PubMed]13. Rogawski MA, Porter RJ. Antiepileptic drugs: pharmacological mechanisms and clinical efficacy with consideration of promising developmental stage compounds. Pharmacol Rev 1990;42:223–286.

[PubMed]14. Glauser TA, Clark PO, Strawsburg R. A pilot study of topiramate in the treatment of infantile spasms. Epilepsia 1998;39:1324–1328.

[Article] [PubMed]15. Glauser TA, Miles MV, Tang P, Clark P, McGee K, Doose DR. Topiramate pharmacokinetics in infants. Epilepsia 1999;40:788–791.

[Article] [PubMed]16. Mikaeloff Y, de Saint-Martin A, Mancini J, Peudenier S, Pedespan JM, Vallée L, et al. Topiramate: efficacy and tolerability in children according to epilepsy syndromes. Epilepsy Res 2003;53:225–232.

[Article] [PubMed]17. Zou LP, Ding CH, Fang F, Sin NC, Mix E. Prospective study of first-choice topiramate therapy in newly diagnosed infantile spasms. Clin Neuropharmacol 2006;29:343–349.

[Article] [PubMed]18. Kwon YS, Jun YH, Hong YJ, Son BK. Topiramate monotherapy in infantile spasm. Yonsei Med J 2006;47:498–504.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]19. Ben-Menachem E, Sander JW, Stefan H, Schwalen S, Schäuble B. Topiramate monotherapy in the treatment of newly or recently diagnosed epilepsy. Clin Ther 2008;30:1180–1195.

[Article] [PubMed]20. Sorel L, Dusaucy-Bauloye A. Findings in 21 cases of Gibbs' hypsarrhythmia; spectacular effectiveness of ACTH. Acta Neurol Psychiatr Belg 1958;58:130–141.

[PubMed]21. Bobele GB, Bodensteiner JB. The treatment of infantile spasms by child neurologists. J Child Neurol 1994;9:432–435.

[Article] [PubMed]22. Ben-Menachem E, Henriksen O, Dam M, Mikkelsen M, Schmidt D, Reid S, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate as add-on therapy in patients with refractory partial seizures. Epilepsia 1996;37:539–543.

[Article] [PubMed]23. Biton V, Montouris GD, Ritter F, Riviello JJ, Reife R, Lim P, et al. Topiramate YTC Study Group. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of topiramate in primary generalized tonic-clonic seizures. Neurology 1999;52:1330–1337.

[Article] [PubMed]24. Elterman RD, Glauser TA, Wyllie E, Reife R, Wu SC, Pledger G. Topiramate YP Study Group. A double-blind, randomized trial of topiramate as adjunctive therapy for partial-onset seizures in children. Neurology 1999;52:1338–1344.

[Article] [PubMed]25. Sachdeo RC, Glauser TA, Ritter F, Reife R, Lim P, Pledger G. Topiramate YL Study Group. A doubleblind, randomized trial of topiramate in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Neurology 1999;52:1882–1887.

[Article] [PubMed]26. Hsieh MY, Lin KL, Wang HS, Chou ML, Hung PC, Chang MY. Low-dose topiramate is effective in the treatment of infantile spasms. Chang Gung Med J 2006;29:291–296.

[PubMed]27. Korinthenberg R, Schreiner A. Topiramate in children with west syndrome: a retrospective multicenter evaluation of 100 patients. J Child Neurol 2007;22:302–306.

[Article] [PubMed]28. Lee IK, Kim SK, Lee R, Kwon YS, Lee JH, Chae JH, et al. Efficacy of topiramate in West syndrome. J Korean Epilepsy Soc 2000;4:27–29.29. Albsoul-Younes AM, Salem HA, Ajlouni SF, Al-Safi SA. Topiramate slow dose titration: improved efficacy and tolerability. Pediatr Neurol 2004;31:349–352.

[Article] [PubMed]30. Peltzer B, Alonso WD, Porter BE. Topiramate and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) as initial treatment for infantile spasms. J Child Neurol 2009;24:400–405.

[Article] [PubMed] [PMC]31. Appleton RE. Vigabatrin in the management of generalized seizures in children. Seizure 1995;4:45–48.

[Article] [PubMed]32. Suzuki Y, Nagai T, Ono J, Imai K, Otani K, Tagawa T, et al. Zonisamide monotherapy in newly diagnosed infantile spasms. Epilepsia 1997;38:1035–1038.

[Article] [PubMed]33. Karvelas G, Lortie A, Scantlebury MH, Duy PT, Cossette P, Carmant L. A retrospective study on aetiology based outcome of infantile spasms. Seizure 2009;18:197–201.

[Article] [PubMed]34. Ben-Zeev B, Watemberg N, Augarten A, Brand N, Yahav Y, Efrati O, et al. Oligohydrosis and hyperthermia: pilot study of a novel topiramate adverse effect. J Child Neurol 2003;18:254–257.

[Article] [PubMed]35. Kossoff EH, Pyzik PL, Furth SL, Hladky HD, Freeman JM, Vining EP. Kidney stones, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2002;43:1168–1171.

[Article] [PubMed]36. Langtry HD, Gillis JC, Davis R. Topiramate. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and clinical efficacy in the management of epilepsy. Drugs 1997;54:752–773.

[Article] [PubMed]37. Levisohn PM. Safety and tolerability of topiramate in children. J Child Neurol 2000;15(Suppl 1): S22–S26.

[Article] [PubMed]38. Sen HA, O'Halloran HS, Lee WB. Case reports and small case series: topiramate-induced acute myopia and retinal striae. Arch Ophthalmol 2001;119:775–777.

[PubMed]

About

About Browse articles

Browse articles For contributors

For contributors