All issues > Volume 55(1); 2012

An overview of the national immunization policy making process: the role of the Korea expert committee on immunization practices

- Corresponding author: Hee Yeon Cho, MD. Department of Pediatrics, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, 50 Irwon-dong, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, Korea. Tel: +82-2-3410-3539, Fax: +82-2-3410-0043, choheeyeon@gmail.com

- Received November 19, 2011 Accepted December 07, 2011

- Abstract

-

The need for evidence-based decision making in immunization programs has increased due to the presence of multiple health priorities, limited human resources, expensive vaccines, and limited funds. Countries should establish a group of national experts to advise their Ministries of Health. So far, many nations have formed their own National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs). In the Republic of Korea, the Korea Expert Committee on Immunization Practices (KECIP), established by law in the early 1990s, has made many important technical recommendations to contribute to the decline in vaccine preventable diseases and currently functions as a NITAG. It includes 13 core members and 2 non-core members, including a chairperson. Core members usually come from affiliated organizations in internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics, microbiology, preventive medicine, nursing and a representative from a consumer group, all of whom serve two year terms. Non-core members comprise two government officials belonging to the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) and the Korea Food and Drug Administration. Meetings are held as needed, but at least twice a year, and sub-committees are formed as a resource for gathering, analyzing, and preparing information for the KECIP meetings. Once the sub-committees or the KCDC review the available data, the KECIP members discuss each issue in depth and develop recommendations, usually by a consensus in the meeting. The KECIP publishes national guidelines and immunization schedules that are updated regularly. KECIP's role is essentially consultative and the implementation of their recommendations may depend on the budget or current laws.

- Introduction

- Introduction

Immunization is among the most effective public health measures to prevent contagious disease. Recommendations concerning the use of the vaccines and the introduction of new vaccines, based on evidence, are critical to improving a country's public health. To facilitate the immunization policy- making process, some countries have established national technical advisory bodies, often referred to as National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs)1,2). The World Health Organization (WHO) has placed a higher priority on the development of a national decision making process for immunization concerns and is working through its regional and country offices, and with various partners to support countries with the establishment, strengthening, and functioning of their NITAGs2). According to WHO guidelines, a NITAG is ideally an independent, expert advisory committee that is used as a technical resource supplying guidance to national policy makers and program managers to enable them to make evidence-based, immunization-related policy and program decisions2). The proposed broad and general terms of reference for such a group are to: 1) conduct policy analyses and determine optimal national immunization policies; 2) guide the national government and the national immunization program on the formulation of strategies for the control of vaccine preventable diseases (VPD) through immunization; 3) advise national authorities on the monitoring of the immunization program so that the impact can be measured and quantified; 4) advise the government on the collection of important disease and vaccine uptake data and information; 5) identify the need for further data for policy making; 6) guide, where appropriate, organizations, institutions or government agencies in the formulation of policies, plans and strategies for research and development of new vaccines and vaccine delivery technologies, for the future2). The majority of industrialized, and some developing countries, have formally constituted a NITAG to guide immunization policies1). Other countries are starting to work towards, or are contemplating, the establishment of such bodies1). Still others have not even embarked on thinking about such a body1). Each country can adjust the roles and functions of their NITAGs to their own current needs and resources. Therefore, there is a NITAG that is referred to as the Korea Expert Committee on Immunization Practices (KECIP) that serves the Republic of Korea. This committee is an advisory organ of the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MoHW) and has played an increasingly larger and more visible role in the decision-making process during the introduction of new vaccines in to the National Immunization Program (NIP) and implementation of the novel influenza H1N1 vaccination in recent years3). This report presents an overview of the history, structure, function and legal authority of KECIP, and reviews the process of recommendation development.

- History of the KECIP

- History of the KECIP

The MoHW ordered the establishment of the Korea Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (KACIP) in June 1992 to advise the MoHW on the control of VPD and immunization-related policy3). In the United States (US), the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices was established in 1964 by the US Surgeon General to assist in the prevention and control of communicable disease4). In the United Kingdom, the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunization, which was originally an advisory board for polio immunization, was established in 19635). With the issue of adverse events associated with the Japanese Encephalitis vaccination, the KACIP became a legal entity under the Prevention of Contagious Diseases Act in August, 19943). With its legal designation came detailed rules concerning the structure, terms of reference and functioning of the committee3). The terms of reference for KACIP are to: 1) designate diseases to be targeted for immunization and remove diseases from the list, as needed; 2) develop plans for the control of VPD; and 3) develop practical guidelines and policies for immunization3). The first committee established under these rules began in February 1995 and discussed a number of key topics3). The committee also established a sub-committee for the investigation of vaccine-related injuries, which was separated from the KACIP and became the Advisory Committee on Vaccine Injury Compensation in 20033). In December 2010, the Prevention of Contagious Diseases Act was revised to the Prevention of Infectious Disease Act and with this change, the KACIP had to be changed to the KECIP which plays the role of a sub-expert committee of the Governing Committee of Infectious Disease6,7). Previously, the Prevention of Contagious Diseases Act ruled the composition, terms of reference, member selection process and meeting process. Since December 2010, the Regulations for the Prevention of Infectious Disease provide the composition, meeting process and selection of members of the KECIP7). In addition, the established rules for the Korea Expert Committee on Immunization Practices of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) state terms of reference, composition of sub-committees, meeting preparation and the scope of work of the KECIP8).

- Composition of the KECIP

- Composition of the KECIP

According to WHO guidelines, the composition of the group should include two categories of members: core and non-core members2). All core members should be independent and credible experts who serve in their own capacity and who do not represent the interests of a particular group or stakeholder2). It is recommended that the committee be multidisciplinary and represent a broad range of skills and expertise through the selection of technically sound and experienced individuals as members2). When feasible, it is recommended for countries to include experts as core members from the following disciplines: clinical medicine (pediatrics and adolescent medicine, adult medicine, geriatrics, and so on), epidemiologists, infectious disease specialists, microbiologists, public health, immunology, vaccinology, immunization program specialists, and health systems and delivery2). The KECIP consists of a chairperson and specialists in internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics, microbiology, preventive medicine, nursing and a representative from a consumer group8). The aformentioned members can be counted among the core members. The KECIP also includes the Director of Disease Prevention at KCDC and the Director of Biologics at the Korea Food and Drug Administration (KFDA) as non-core members8). Non-core members can be subdivided into two groups, ex officio and liaison members2). Ex officio members hold key positions with the important government entities they represent (e.g., KFDA and KCDC) and their presence is solicited because of the positions that they hold2). Liaison members generally represent various important professional societies or associations, other national advisory committees, and sometimes key technical partners (e.g., WHO and The United Nations Children's Fund)2). Apart from the two government officials mentioned above, all other members usually come from the affiliated organizations, which will each nominate one member. The total number of Committee members is usually around 15. There are no fixed rules about the size of a NITAG but this can be influenced by local considerations such as the need for geographic representation, the size of the country, the availability of resources and so on2). Experience has shown that successful committees function with about 10 to 15 core members2). For committee with a small number of members the effect of absentees would be particularly noticeable2). Too large a committee is more costly and can be difficult to manage2). Groups with an odd number of members may be more effective for resolving disagreements and reaching speedier decision2). The Secretariat of the Committee is within the KCDC, which funds, organizes, and prepares for the meetings. The Chairperson rotates every term and can be selected from any field or affiliated organization.KECIP members are appointed by the Chairperson of the Governing Committee of Infectious Disease, a vice-minister of the MoHW, and, with the exception of the Director of Disease Prevention at the KCDC and the KFDA's director of Biologics, they serve for a term of 2 years8). Members can serve more than one term, but, although there is no formal rule dictating the length of time members can serve on the Committee, members usually do not serve more than two terms. A process of rotation for core members with limited durations of terms of service is essential for the credibility of the group, and standard operating procedures that specify the nomination, rotation, and termination processes should be developed2). Terms of three to four years, with or without provisions for renewal of a term, are common practice4,5,9).

- Scope that the Committee addresses

- Scope that the Committee addresses

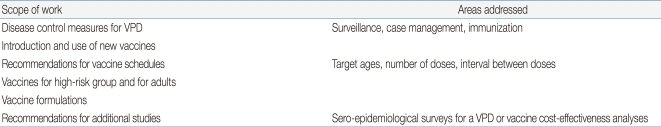

According to the written rules governing the KECIP, contained with-in the established rules of the KCDC, the Committee must meet at least two times a year, and additional meetings can be held, as needed, upon the request of the Chairperson of the Governing Committee of Infectious Disease or more than half of the Committee members, with approval by the Chairperson of the KECIP8). Nevertheless, there should be flexibility in calling a meeting at any point to discuss important decisions or urgent matters in rare occasions that may require the organization of additional meetings. There should always be regular or fixed meetings scheduled in advance2). It is recommended that the NITAGs meet regularly and at least twice a year2). Several groups such as those in Canada, the United States or the United Kingdom operate successfully with three or four meetings a year4,5,9).The Director of the Division of VPD control and the NIP in the KCDC sets up the agenda for each meeting, based on suggestions from KECIP members, KCDC staff, other experts and ex-officio members, and also,-members of KECIP sub-committees.The scope of work of the Committee includes the various issues shown in Table 1.As written in the established rules of the KCDC, KECIP meetings are, in principle, open to the public, and those people wishing to attend a meeting as observers, such as vaccine producers,-and members of civil organizations or academia, should submit a written application at least 5 days before the meeting8). However, the Chairperson of the KECIP can hold a meeting behind closed doors, if particularly sensitive or controversial topics are being discussed8).

- Sub-committees and special working groups

- Sub-committees and special working groups

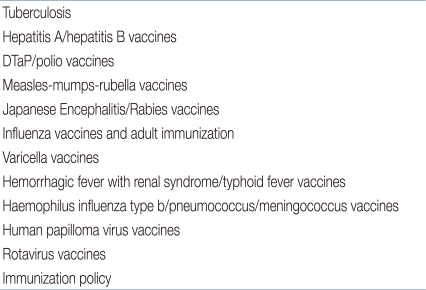

In 2003, the KACIP established a number of sub-committees that function as working groups to gather, analyze, and present information, and also make recommendations on specific topics to inform the Committee's decision-making3). When the KACIP had to be changed to the KECIP in December 2010, 12 sub-committees, each with a specific area of expertise or focus were reestablished (Table 2)8). They are usually made up of less than 20 members, including some KECIP members, representatives of affiliated organizations and some from academia, as well as other external experts8). The director of the KCDC appoints the chairs of the sub-committees8). Sub-committee members are recommended by the KCDC Director, the Chairperson of the sub-committee, and KECIP members, and are approved by the KCDC Director8). As with KECIP meetings, the Committee must meet at least two times a year, and additional meetings can be held, as needed, such as when a topic related to their areas of focus is on the agendas of upcoming KECIP meetings8).In addition to these sub-committees, specific working groups have been established, if needed, by the KCDC. These working groups function in very much the same manner as the sub-committee, reporting their findings and making recommendations to the KECIP3). Such working groups are the Advisory Committee for the Validation of Measles Elimination Status, the Advisory Committee on the Prevention of hepatitis B Vertical Transmission, and the Advisory Committee on H1N1 Influenza Virus3).

- The decision-making process

- The decision-making process

When a decision has been made to add a topic to the agenda for the KECIP to address, the KCDC requests the appropriate sub-committee to review all relevant data, gather the opinions of experts, and suggest a policy recommendation. The necessary data includes the disease burden in Korea, such as the clinical characteristics of the disease, incidence, mortality, and case fatality rates. The sub-committee also analyzes data on the efficacy, effectiveness, and safety of the vaccine. Sources of information on the vaccine include clinical trials conducted both in Korea and in other countries, WHO position papers, recommendations published by the U.S Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control3). Economic data on the disease and vaccine, including the cost, affordability, and financial sustainability of implementing the new vaccine program, as well as the vaccine's cost-effectiveness, should be reviewed by the KCDC, the sub-committee, and the KECIP.Sub-committees also make recommendations concerning measures for controlling the VPD they focus on that go beyond immunization3). These recommendations included the isolation of the patients, the prophylactic management among the patient's contacts, the diagnostic methods, the disease surveillance and the immunization3). When sub-committees make recommendations, the KCDC can order the implementation of the medical-related recommendations in public health facilities. At the same time, the vaccine-related recommendations are sent to the KECIP to address them at its meeting.Once the sub-committee reviews the epidemiological, vaccine, and economic data, members try to reach a consensus on recommendations concerning control measures for the disease in question, of which includes immunization3). If the sub-committee cannot reach a consensus, it is the prerogative of the Chairperson to decide what recommendations to give to the KECIP3). The officer from the KCDC summarizes the data, opinions, and recommendations from the sub-committee and prepares a bound document for KECIP meetings.During the meetings of the KECIP, experts, officials from the KFDA or the KCDC or members of the relevant sub-committee are asked to express their opinions. The KECIP members discuss each issue in depth and develop recommendations, usually by consensus. Minutes of each meeting with the focus on the main conclusions and recommendations must be available and endorsed by the group after the meeting. An officer of the KCDC records the results of the meeting, which the KECIP Chairperson submits to the Chairperson of the Governing Committee of Infectious Disease, who is a Vice-Minister of the MoHW8). It must be decided if the minutes are going to be public or private. The minutes of the KECIP meetings are given to the KCDC Director and other staff, but are not made public.While most decisions made by the KECIP are approved by the MoHW and implemented, KECIP recommendations are not legally binding. Sometimes it takes time for them to be implemented due to a lack of funding or the need to revise laws in order to enact the policy change. The role of the NITAGs is essentially consultative and the ultimate decisions about programs remain in the hands of government officials2). One of the benefits of a NITAG is to help keep the national authorities and those working for the national immunization program updated on the latest scientific developments in the area of vaccines and VPD epidemiology and control2).If a recommendation is approved by the MoHW, the KCDC will develop a budget to cover the costs of the new policy change and plan the steps necessary to implement the recommendation, working with both public and private health facilities3). The Public Relations Department of the KCDC prepares public education materials, such as brochures, posters, vaccine information statements, or factsheets to inform the public and medical community of the new recommendations3). The KCDC publishes a national reference manual on the epidemiology and prevention of VPD in cooperation with the KECIP, sub-committees, and affiliated organizations, and it revises the manual to include the new recommendations.One key to improving routine immunization programs and sustainably introducing new vaccines and immunization technologies is for countries to ensure that they have the necessary data and a clear decision-making processes2). To make informed decisions involving immunization, countries are encouraged to establish a NITAG1,2). The KECIP has made many important technical recommendations that have contributed to a decline in VPD burden on the basis of collected data for 20 years and can be listed as a successful example of a NITAG.

- References

- 1. Bryson M, Duclos P, Jolly A, Cakmak N. A global look at national Immunization Technical Advisory Groups. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1): A13–A17.

[Article] [PubMed]2. Duclos P. National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs): guidance for their establishment and strengthening. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1): A18–A25.

[Article] [PubMed]3. Cho HY, Kim CH, Go UY, Lee HJ. Immunization decision-making in the Republic of Korea: the structure and functioning of the Korea Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1): A91–A95.

[Article] [PubMed]4. Smith JC. The structure, role, and procedures of the U.S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1): A68–A75.

[Article] [PubMed]5. Hall AJ. The United Kingdom Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation. Vaccine 2010;28(Suppl 1): A54–A57.

[Article] [PubMed]6. Ministry of Health and Welfare (2010) [Internet]. The Prevention of Infectious Disease Act. c2011;cited 2011 Nov 3. Seoul: Korea Ministry of Government Legistraion, Available from: http://www.law.go.kr.7. Ministry of Health and Welfare (2010) [Internet]. The Regulations for the Prevention of Infectious Disease. c2011;cited 2011 Nov 3. Seoul: Korea Ministry of Government Legistraion, Available from: http://www.law.go.kr.8. The established rules for the Korea Expert Committee on Immunization Practices [Internet]. c2011;cited 2011 Nov 3. Cheongwon: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr.

About

About Browse articles

Browse articles For contributors

For contributors