Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 54(1); 2011 |

Abstract

Purpose

Korean adolescents have severe nighttime sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness because of their competitive educational environment. However, daytime sleep patterns and sleepiness have never been studied using age-specific methods, such as the pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS). We surveyed the daytime sleepiness of Korean adolescents using a Korean translation of the PDSS.

Methods

We distributed the 27-item questionnaire, including the PDSS and questions related to sleep pattern, sleep satisfaction, and emotional state, to 3,370 students in grades 5-12.

Results

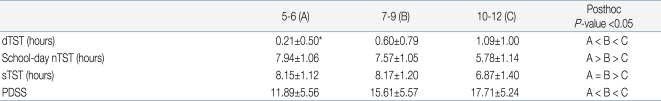

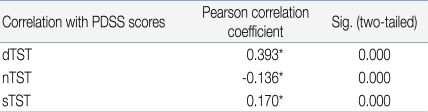

The amount of nighttime sleep decreased significantly with increasing age. During weekday nights, 5-6th graders slept for 7.95±1.05 h, 7-9th graders for 7.57±1.05 h, and 10-12th graders for 5.78±1.13 h. However, the total amounts of combined daytime and nighttime sleep during weekdays were somewhat greater, 8.15±1.12 h for 5-6th graders, 8.17±1.20 h for 7-9th graders, and 6.87±1.40 h for 10-12th graders. PDSS scores increased with age, 11.89±5.56 for 5-6th graders, 16.57±5.57 for 7-9th graders, and 17.71±5.24 for 10-12th graders. Higher PDSS scores were positively correlated with poor school performance and emotional instability.

Conclusion

Korean teenagers sleep to an unusual extent during the day because of nighttime sleep deprivation. This negatively affects school performance and emotional stability. A Korean translation of the PDSS was effective in evaluating the severity of daytime sleepiness and assessing the emotional state and school performance of Korean teenagers.

Sufficient sleep is essential for the physical growth, emotional stability, and maintenance of cognitive function in adolescence1). Excessive daytime sleepiness attributable to sleep deprivation or a sleep disorder is known to reduce work efficiency and to cause traffic and industrial accidents2). Chronic sleep deprivation among adolescents inhibits pre-frontal lobe functions, such as working memory, judgment, and insight, resulting in impairment of learning and school performance. The increased emotional lability and depression associated with sleep deprivation also makes it difficult for sleep-deprived students to adjust to school life3-12).

Modern-day adolescents get much less sleep than was the case in the 20th century. In particular, excessive use of the internet and other media has reduced sleep time13, 14). It was noted that the average sleep duration of adolescents was 7.6-8.6 hours, 0.4-1.4 hours less than what is needed5). Adolescents in higher grades usually get even less nighttime sleep and experience more marked differences when sleep duration on weekdays and weekends is compared10, 15-17). In Japan, where the educational environment is similar to that of Korea, sleep duration was 7.2-7.8 hours among 10-12th graders, thus shorter than that of adolescents in the West18).

Korean parents place great emphasis on education, and adolescents often take extra classes or private lessons, contributing to chronic sleep deprivation. In particular, 11-12th graders in Korea have an average nighttime sleep duration of 4.9-5.5 hours, much less than students in Japan, where parents also place great emphasis on education19-21). This severe chronic nighttime sleep deprivation can lead to excessive daytime sleepiness and lack of attention in class, an increase in emotional lability and depression, and may also be associated with increases in violence and suicide among adolescents22). A previous report indicated that about 70% of Korean adolescents were worried about nighttime sleep quality and over 20% complained of excessive daytime sleepiness. However, the daytime sleep patterns and sleepiness of Korean adolescents have never been studied using an age-specific measure of sleepiness, such as the well-known pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS)23).

In the present study, we examined the sleep patterns and daytime sleepiness of Korean adolescents using a Korean version of the PDSS and studied the relationship between PDSS data, and adjustment to school life and academic achievement.

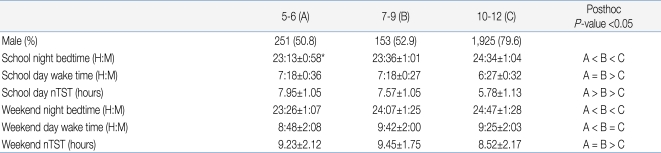

We administered sleep questionnaires to 3,379 students in grades 5-12, in their classrooms, in schools situated in the southern region of Gyeonggi-do and Seoul (Korea), from May to November 2009. A total of 3,201 students successfully completed the survey (5-6th grade: 532, 7-9th grade: 302, 10-12th grade: 2545). The male/female ratio was about equal for students in grades 5-9. However, more boys than girls were in grades 10-12 (79.6% boys; 20.4% girls) (Table 1).

The entire sleep questionnaire contained 27 items, and included four questions on sleep/wake patterns, two questions on time spent at school, two questions on sleep satisfaction, three questions on abnormal sleep behavior, two questions on school adjustment, one question on performance, three questions on after-school activities (including the taking of private lessons), two questions on emotional state, and eight questions from the Korean translation of the PDSS (Appendix 1). We surveyed sleep patterns on weekdays and weekends during the previous 4 weeks. The sum of total sleep time (sTST) was calculated by addition of average nighttime (nTST) and daytime total sleep time (dTST). The dTST were computed as median values: 15 minutes of dTST for nap of less than 30 minutes a day, 45 minutes for nap between 30 minutes and 1 hour, 1 hour 30 minutes for nap of less than 2 hours, and 2 hours 30 minutes for more than 2 hours of nap. Questions about emotional state, abnormal sleep behavior and school adjustment were assessed using a Likert-scale format. Two items about school adjustment were the questions about participants' happiness and loneliness during school time. School performance was measured by asking students "What's your grade point average in last semester?" The self-reported choices were: 90 or above, 80-89, 70-79, 60-69, and less than 60. Two questions about mood state were how often the responders were calm and got angry with themselves or others over the last 4 weeks. Responses to the questions were "all the time (6-7 days/week)," "frequently (3-5 days/week)," "sometimes (1-2 days/week)," "seldom," or "never."

We also assessed participants' daytime sleepiness using the translated version of PDSS. Items about PDSS were scored from 0 to 4 (never = 0; seldom = 1; sometimes = 2; frequently = 3; always = 4). Total PDSS score (ranging from 0-32) was calculated by adding scores on each of the eight questions; a higher score indicated more sleepiness. Means and standard deviations for the PDSS score across grade level were assessed. Correlation coefficient between nTST, dTST, sTST and PDSS were assessed. ANOVAs were performed to examine group differences such as mood, grade, school adjustment and performance for TST and PDSS. Computing statistical reliability of PDSS, Cronbach's alpha was calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the CHA Medical Center.

On school nights, students in grades 5-6 went to sleep at 23:13±0:58, those in grades 7-9 at 23:36±1:01, and students in grades 10-12 at 24:34±1:05. On weekends, bedtime was delayed by about 10-30 minutes. On school days, wake time was 7:18±0:36 for students in grades 5-6, 7:18±0:27 for those in grades 7-9; whereas students in grades 10-12 woke up at 6:27±0:32, thus about 50 minutes earlier than did elementary and middle school students. Wake times on weekends were delayed by about 1.5 hours for students in grades 5-6, by about 2.5 hours for those in grades 7-9, and by 3 hours for students in grades 10-12. The nTST on schooldays were 7:57±1:03 hours for 5-6th graders, 7:34±1:03 hours for 7-9th graders, and 5:47±1:08 hours for 10-12th graders, indicating a diminution in sleep time of students in higher grades. The nTST on weekends increased by about 1.5 hours for 5-6th graders, 2 hours for 7-9th graders, and 3 hours for 10-12th graders; the difference between weekday and weekend sleep time was thus greater for students in higher grades (Table 1).

Of all 5-6th graders, 30.2% reported that they took naps during the daytime, whereas the figures for 7-9th graders and 10-12th graders were 74% and 94.4%, respectively. This indicates that the level of daytime sleepiness among Korean adolescents is considerable, and becomes more severe as students get older. Daytime sleep was less than 1 hour in duration for most elementary- and middle school students, but nap time increased as student age rose. Only 5.6% of high school students reported that they did not get sleepy during the daytime. A total of 45.7% of high school students reported that they napped for less than 1 hour, 42.4% took naps of 1-3 hours, and 6.2% napped for 3-5 hours, indicating that daytime sleepiness caused by lack of nighttime sleep was severe. Students in grades 5-6 napped for an average of 12 minutes at school, those in grades 7-9 for 35 minutes, and those in grades 10-12 for about 1 hour, thus showing a statistically significant rise in nap time with advancing school grade level.

Students in grades 5-6 reported an sTST of 8.15±1.12 hours, those in grades 7-9 8.17±1.20 hours, and students in grades 10-12 6.87±1.40 hours. Thus, elementary and middle school students had similar sTSTs, but high-school students suffered significantly less sleep time (Table 2). The nTST of high school students fell significantly as students entered the upper grades. In particular, 10th grade students reported an nTST of 6.17±1.13 hours, 11th graders 5.81±1.04 hours, and 12th graders 5.27±1.07 hours. However, the sTST was 7.04±1.35 hours for 10th graders, 6.87±1.34 hours for 11th graders, and 6.65±1.49 hours for 12th graders, with no statistically significant difference evident among grades.

On the sleep satisfaction, of all 5-6th graders, 24.8% reported that they had insufficient sleep, whereas the figures for 7-9th graders and 10-12th graders were 40.9% and 58.0%, respectively. This finding indicates that the level of sleep satisfaction of the Korean adolescent is significantly low, and become more severe as students become older.

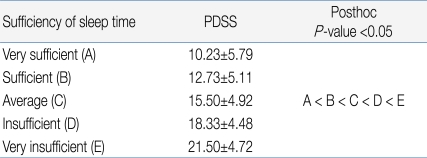

The PDSS measures daytime sleepiness of children and adolescents, and a higher score indicates more sleepiness. In the present survey, the mean PDSS score of the group who considered that sleep time was very sufficient was 10.23±5.79, and the PDSS score rose as sleep time became less adequate (Table 3).

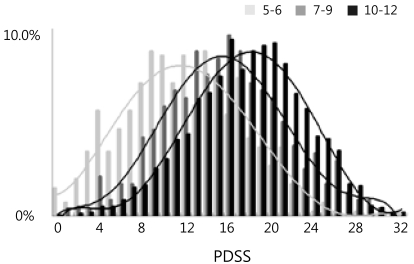

The average PDSS score of all students was 16.63±5.72. In 5-6th graders, the score was 11.89±5.56, in 7-9th graders 16.57±5.57, and in 10-12th graders 17.71±5.24 (Fig. 1). Cronbach's alpha, a measure of statistical reliability, was similar for all age groups (all students: 0.67; 5-6th graders: 0.68; 7-9th graders: 0.67; and 10-12th graders: 0.62). Correlation analysis of PDSS results and sleep patterns indicated that PDSS scores were negatively correlated with nTST and positively associated with dTST. In other words, a decrease in nTST caused a significant rise in daytime sleepiness, and, even though dTST became greater in older students, the PDSS scores of such students remained elevated (Table 4).

The 5-6th graders attributed lack of sleep during the school week to a need to take private lessons and extra classes, the 7-9th graders identified TV-watching or internet use as responsible for lack of sleep, and the 10-12th graders cited attendance at early classes.

Higher PDSS scores were associated with increased emotional lability and irritability both at school and at home. In particular, students who reported that they were content almost all of the time had lower PDSS scores than did those who stated the opposite. Abnormal sleep behavior, including being late for school because of oversleeping, or going to sleep after 3 am, was significantly correlated with elevation in PDSS score.

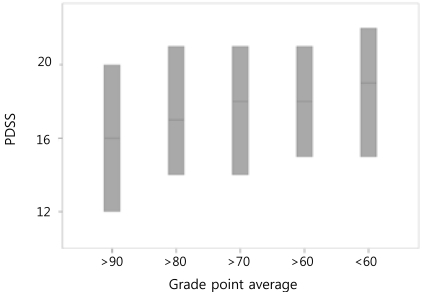

Finally, we found that high academic achievement was associated with a low PDSS score. In particular, students with low PDSS scores had better grade point averages, and significant differences in PDSS scores were evident among students with averages of over 90 points, of 80-90 points, and of 70-80 points. However, no significant difference in PDSS score was apparent when students with grade point averages of 60-70 points and those with averages below 60 were compared (Fig. 2).

Our study indicates that the average school day nTST of Korean adolescents is 7.95±1.05 hours for 5-6th graders, 7.57±1.05 hours for 7-9th graders, and 5.78±1.13 hours for 10-12th graders. The school day sTST are 8.15±1.12 hours for 5-6th graders, 8.17±1.20 hours for 7-9th graders, and 6.87±1.40 hours for 10-12th graders, thus making sleep deprivation less severe. Nonetheless, 9 hours of sleep is considered necessary for adolescents, and all students were thus sleep-deprived10, 24). In particular, the nTST of 9-12th graders was significantly less than that of younger students, but the sTST did not differ significantly between these two groups because of an increase in dTST. However, the sTST of 9-12th graders remained almost 2 hours less than the recommended sleep time.

In this study most of 7-12th graders attributed their night time sleep deprivation to use of internet or early school start time, not excessive after-school classes. Unsurprisingly it is suggested that Korean adolescents seem to accept their excessive after-school classes in school or tutoring in institution involuntarily in highly competitive educational environment. For 10-12th graders arriving time at home is around 9-10 p.m. whereas for 7-9th graders, 3-4 p.m. is usual arriving time in our study. Moreover, 63.5% of high school students had their private tutoring for 1 to 4 hours after school, and 77.9% of middle-school students in this study received tutoring. Undoubtedly excessive classes or tutoring is a major cause of sleep deprivation, even though excessive use of internet at night is also contributing to sleep deprivation in Korean adolescents.

The average PDSS score of all students was 16.63±5.72, but increased significantly as students became older. As PDSS score rose, emotional lability and abnormal sleep behavior also increased. Moreover, a high PDSS score was negatively correlated with academic achievement with statistical significance. Thus, we conclude that the Korean version of the PDSS accurately assesses both daytime sleepiness and other factors related to academic achievement by Korean adolescents.

In 1981, Carskadon, at Stanford University, commenced detailed studies of sleep deprivation in 12 adolescents5, 24). Previous works had shown that sleep latency (the length of time that it takes to accomplish the transition from full wakefulness to sleep) decreased as sleep deprivation rose, and that the extent of sleepiness could be measured objectively5). Subsequent studies showed that sleep deprivation increased daytime sleepiness, and had negative effects on all of cognition, memory, fine motor control, and mood3, 10, 25, 26). Moreover, if sleep deprivation persisted for a long period, higher brain function was impaired, BMI rose, blood pressure elevated, glucose intolerance increased, and adverse effects on the immune and cardiac system were evident26-29). Adolescents and children have similar physiological sleep requirements, but both the time of entry into and awakening from sleep occur about 2 hours later in adolescents, as a result of the physiological changes associated with puberty. Moreover, the level of daytime sleepiness becomes higher physiologically in adolescents than in children30). In the present study, we found that total sleep time did not differ greatly when elementary- and middle-school students were compared, but that PDSS scores of middle-school students were significantly higher than those of students in elementary school. It is thought that reduced nighttime sleep and changes in the sleep cycle increase daytime sleepiness in adolescents.

Studies in the USA on the relationship between sleep time and academic achievement indicated that adolescents slept for an average of 7.6 hours. However, students in grades 10, 11, and 12 had average school day sleep times of 7.3 hours, 7.0 hours, and 6.9 hours, respectively13). Moreover, insufficient sleep time had an adverse affect on student grades25). Studies on middle-school students in New Zealand found that school day sleep time was about 8.7 hours, close to the recommended amount, but that students in higher grades had less school day sleep and more sleep on weekends, as has also been found in other countries. In India, the sleep time of middle- and high-school students was 7.6-8.0 hours, whereas in Okinawa (Japan), the figure was 7.2-7.9 hours10, 15-18). Previous studies in Korea have found that the average sleep time of high-school students in grades 10-12 was only 4.9-5.5 hours, indicating that many such students were severely sleep-deprived19-21). In the present study, we considered daytime sleep hours when calculating sleep time totals, and found that sleep deprivation was not quite as severe as previously indicated. However, our results do confirm that Korean students are sleep-deprived.

The Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) and the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT) both objectively measure daytime sleepiness in adolescents, but these tools can be difficult to use, and are not widely employed in epidemiologic studies5). Simple survey methods are often preferable. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) can be used for long-term measurement of sleepiness and the Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS) is valuable to assess for short-term daytime sleepiness1, 31-33). The ESS has been employed in previous studies of daytime sleepiness in Korean adolescents. However, this test explores sleepiness during driving, and asks whether sleep-inducing medication was taken; the test is thus more appropriate for adults rather than adolescents21). The PDSS has eight questions, each with five possible answers, and studies in the USA, Argentina, and Taiwan have found that this questionnaire accurately assesses adolescent daytime sleepiness23, 34, 35). In the present study, we determined that the Korean version of the PDSS was appropriate for evaluation of sleepiness in Korean adolescents, and that higher scores were associated with emotional lability and poor school performance. Thus, the PDSS is a simple test that provides accurate results and that can easily be used to test large populations of adolescents or children.

Our study had some limitations. First, the self-reported data on sleep patterns were dependent on subjective memory, and school record data were also imparted by the students. Second, there was a predominance of males in the higher grades, and our results may thus not be applicable to other student populations. Previous studies have found that female students tend to rise earlier and to have longer nighttime sleep than do males6, 19). Our results would have been more accurate had we measured sleep deprivation with actigraphy (which assesses rest/activity cycles by sensor), had we evaluated official school records, and had we tested the students using a psychomotor vigilance task (PVT).

In the present study, using a Korean translation of the PDSS, we found that Korean adolescents were severely sleep-deprived and, as a result, daytime sleepiness was a significant problem associated with excessive napping during the day. Sleep-deprivation problems were more severe in upper-grade students. Moreover, although daytime sleep of older students increased sTST, significant daytime sleepiness was still apparent. Many Korean adolescents appear to be locked into inappropriate split sleep states. This compromises adaptation to everyday life, reduces emotional stability, and worsens school performance. Finally, we showed that the Korean translation of the PDSS accurately assessed sleepiness in Korean adolescents and can validly be used to explore emotional status and school performance.

Korea has an excessively competitive educational system, and the need to take extra classes leads to severe restriction of nighttime sleep during the school week, resulting in significant daytime sleepiness. It seems likely that sleep deprivation is related to inattentiveness, depression, and an elevated suicide rate22). Adolescents require appropriate sleep time to assure normal growth and development; to improve school performance; and to guarantee physical, psychological, and spiritual health. We suggest that the importance of appropriate levels of adolescent sleep be taught at homes, schools, and in society.

Notes

The summary of this paper was presented at the 59th Autumn meeting of the Korean Pediatric Society in 2009.

References

1. Banks S, Dinges DF. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med 2007;3:519–528.

2. Carskadon MA. Sleep deprivation: health consequences and societal impact. Med Clin North Am 2004;88:767–776.

3. Dahl RE. The impact of inadequate sleep on children's daytime cognitive function. Semin Pediatr Neurol 1996;3:44–50.

4. Randazzo AC, Muehlbach MJ, Schweitzer PK, Walsh JK. Cognitive function following acute sleep restriction in children ages 10-14. Sleep 1998;21:861–868.

6. Carskadon MA, Wolfson AR, Acebo C, Tzischinsky O, Seifer R. Adolescent sleep patterns, circadian timing, and sleepiness at a transition to early school days. Sleep 1998;21:871–881.

7. Fallone G, Acebo C, Seifer R, Carskadon MA. Experimental restriction of sleep opportunity in children: effects on teacher ratings. Sleep 2005;28:1561–1567.

8. Nixon GM, Thompson JM, Han DY, Becroft DM, Clark PM, Robinson E, et al. Short sleep duration in middle childhood: risk factors and consequences. Sleep 2008;31:71–78.

9. Suratt PM, Barth JT, Diamond R, D'Andrea L, Nikova M, Perriello VA Jr, et al. Reduced time in bed and obstructive sleep-disordered breathing in children are associated with cognitive impairment. Pediatrics 2007;119:320–329.

10. Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev 1998;69:875–887.

12. Sterpenich V, Albouy G, Darsaud A, Schmidt C, Vandewalle G, Dang Vu TT, et al. Sleep promotes the neural reorganization of remote emotional memory. J Neurosci 2009;29:5143–5152.

13. 2006 Sleep in America poll: summary of findings. WB & A Market Research, National Sleep Foundation Available from: http://www.sleepfoundation.org/%5Fcontent/hottopics/2006%5Fsummary%5Fof%5Ffindings.pdf.

14. Choi K, Son H, Park M, Han J, Kim K, Lee B, et al. Internet overuse and excessive daytime sleepiness in adolescents. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;63:455–462.

15. Dorofaeff TF, Denny S. Sleep and adolescence. Do New Zealand teenagers get enough? J Paediatr Child Health 2006;42:515–520.

16. Epstein R, Chillag N, Lavie P. Starting times of school: effects on daytime functioning of fifth-grade children in Israel. Sleep 1998;21:250–256.

17. Gupta R, Bhatia MS, Chhabra V, Sharma S, Dahiya D, Semalti K, et al. Sleep patterns of urban school-going adolescents. Indian Pediatr 2008;45:183–189.

18. Arakawa M, Taira K, Tanaka H, Yamakawa K, Toguchi H, Kadekaru H, et al. A survey of junior high school students' sleep habit and lifestyle in Okinawa. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2001;55:211–212.

19. Shin C, Kim J, Lee S, Ahn Y, Joo S. Sleep habits, excessive daytime sleepiness and school performance in high school students. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2003;57:451–453.

20. Yang CK, Kim JK, Patel SR, Lee JH. Age-related changes in sleep/wake patterns among Korean teenagers. Pediatrics 2005;115:250–256.

21. Lee JH, Cho YW, Sohn SI. Excessive daytime sleepiness and quality of sleep in Korean middle and high school students. J Korean Sleep Soc 2005;2:34–40.

22. 2008 Youth Statistics. Statistics Korea 2008;Available from:

http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=58063.

23. Drake C, Nickel C, Burduvali E, Roth T, Jefferson C, Pietro B. The pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS): sleep habits and school outcomes in middle-school children. Sleep 2003;26:455–458.

24. Carskadon MA, Harvey K, Duke P, Anders TF, Litt IF, Dement WC. Pubertal changes in daytime sleepiness. Sleep 1980;2:453–460.

25. Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Understanding adolescents' sleep patterns and school performance: a critical appraisal. Sleep Med Rev 2003;7:491–506.

26. Walker MP, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron 2004;44:121–133.

27. Guilleminault C, Powell NB, Martinez S, Kushida C, Raffray T, Palombini L, et al. Preliminary observations on the effects of sleep time in a sleep restriction paradigm. Sleep Med 2003;4:177–184.

28. Liu Y, Tanaka H. Overtime work, insufficient sleep, and risk of non-fatal acute myocardial infarction in Japanese men. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:447–451.

29. Allen RP. Article reviewed: Impact of sleep dept on metabolic and endocrine function. Sleep Med 2000;1:149–150.

30. Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep 1993;16:258–262.

31. Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M. The Children's Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ): psychometric properties of a survey instrument for school-aged children. Sleep 2000;23:1043–1051.

32. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991;14:540–545.

33. Hoddes E, Zarcone V, Smythe H, Phillips R, Dement WC. Quantification of sleepiness: a new approach. Psychophysiology 1973;10:431–436.

Fig. 1

Distribution of PDSS Score By Grade. The mean pediatric daytime sleepiness scale (PDSS) score of all students was 16.63 (5.72), that of 5-6th graders 11.89 (5.56), that of 7-9th graders 16.57±5.57), and that of 10-12th graders 17.71 (5.24). Abbreviation: PDSS, pediatric daytime sleepiness scale.

Fig. 2

Association between PDSS score and grade point average (GPA). The central line indicates the median, and the upper and lower boxes bracket the standard deviation. There were significant differences among groups with GPA scores of >90, 80-90, and 70-80.

Table 2

Sleep Time during the Day, Night, Total Sleep, and PDSS Scores of Students in Different Grades

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation