Introduction

Fluid management is an essential component of pediatric practice, especially in intensive care and postoperative contexts. The traditional maintenance fluid in pediatrics is 0.2% saline in 5% dextrose water (DW), as based on the fact that sodium concentration of 30 mEq/L approximates the sodium composition of human breast milk and cow's milk

1). Concerns arose, however, that a hypotonic solution carries risks of water overload and subsequent hyponatremia, which can lead to fatal outcomes

2). Moritz and Ayus

2) introduced the idea of using 0.9% saline as the maintenance fluid, and several succeeding studies, based on the results of randomized trials, have supported this level as the safer choice

3-

5). Yet, universal agreement on fluid sodium concentrations in cases of pediatric maintenance intravenous administration remains elusive. The nineteenth and most recent edition of

Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics6), the most commonly referred textbook, still states that "the usual choices for maintenance fluid therapy in children are 0.5 normal saline (NS) and 0.2 NS" (p. 243), unless the patient has volume depletion, as based on Holliday's method

1). The 10th edition of the

Korean Textbook of Pediatrics7) specifies that hypotonic fluids must be avoided in intensive care contexts, even where children weigh less than 10 kg. Considering that these textbooks are the sources of the primary guidelines for pediatric care, residents might not be as aware as they should be of the most current fluid prescription issues.

In the present study, we performed a survey-based analysis of maintenance fluid prescription practices, targeting resident trainees in pediatrics to evaluate their knowledge and understanding of current fluid therapy issues and awareness regarding hyponatremia.

Materials and methods

A paper-based survey comprising four questions was distributed to residents in-training at six university hospitals in Korea: Seoul National University Hospital, Asan Medical Center, Dongguk University Ilsan Hospital, CHA Bundang Medical Center, Myongji Hospital, and Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital. Each question introduced a clinical scenario in which the respondent was to choose the most appropriate fluid: 1) a six-month-old baby with acute bronchiolitis, 2) a five-year-old child with Henoch-Schöenlein purpura and abdominal pain; 3) a three-year-old who just received a surgery from acute appendicitis, and 4) a one-year-old infant with acute gastroenteritis and dehydration (

Appendix). In each scenario, the condition of oral intake impairment was assumed. The fluid options were as follows:

1) 0.45% NaCl in 5% DW (NAK2)

2) 0.2.0.25% NaCl in DW (SD 1:4, NAK3)

3) 0.9% NaCl (NS)

4) 0.9% NaCl in 5% DW (5% NS) (Appendix).

The survey was designed and structured by Y. Choi (

Appendix). The respondents were informed that their identities were to remain anonymous. The survey data were cross-tabulated by question and fluid option. For the purposes of the analysis, the solutions were categorized as either hypotonic (NAK2, NAK3) or isotonic (NS, 5% NS).

Results

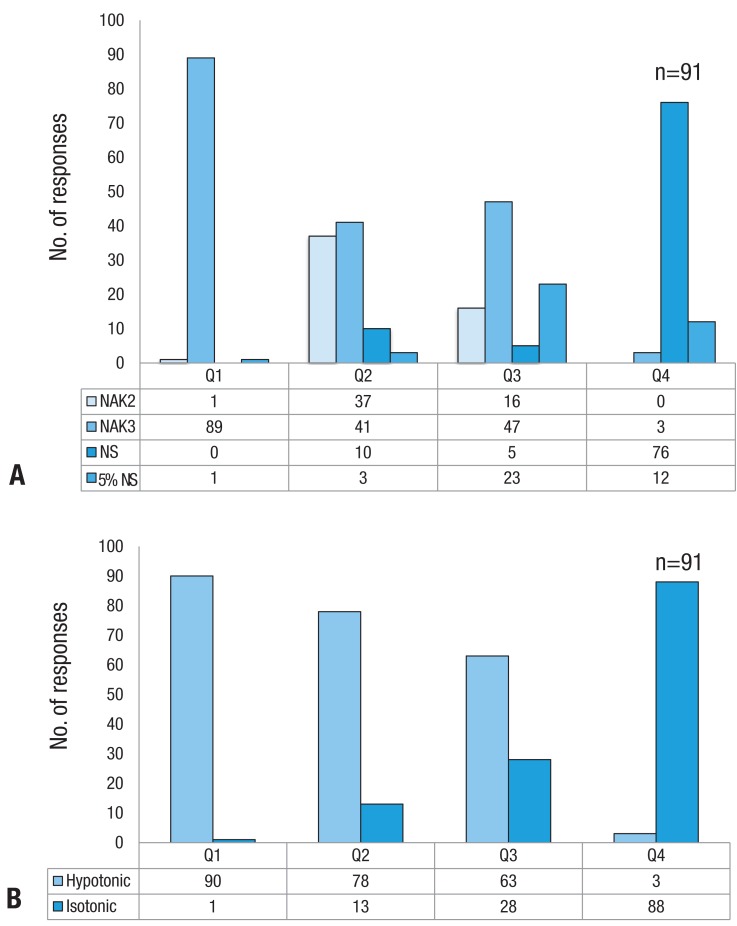

A total of 91 responses were collected. The respondents were evenly distributed among freshman, sophomores, and junior and senior residents.

Fig. 1 depicts the fluids selection for each of the presented scenarios. In the first scenario, a six-month-old patient with acute bronchiolitis, 89 of 91 respondents (97.8%) selected 0.2% NS. In this respiratory disease context, excess antidiuretic hormone (ADH) can be produced

8). The textbooks generally recommend 0.2% NS in 5% DW for patients weighing under 10 kg, but also state that such conditions might be more safely treated with a higher sodium concentration

6,

7). In these situations, 100 mL/kg is the guideline for calculation of the fluid amount, taking into account evaporative losses from the lungs as well

6).

For the second scenario, the five-year-old Henoch-Schöenlein purpura patient with acute abdominal pain, hypotonic fluids were selected by 85.7%, 45.1% of those choosing 0.2% NS. In this clinical setting, as oral intake usually is restricted due to pain, maintenance fluid is supplied intravenously rather than orally. The sodium concentration should be higher than 0.45%, due both to the patient's age (5 years)

5-

7), and the fact that pain also is a well-known stimulant of ADH

2). The amount of fluid can vary, though the textbooks recommend that patients with possible subtle volume depletion receive 20 mL/kg of isotonic fluid over 1.2 hours and then be switched to D5+1/2 NS at a standard maintenance rate

6,

7).

The third scenario involves the choice of fluid for the non peros period after an abdominal operation. Hypotonic fluids were still the preponderant choice (in 69.2% of cases) for postoperative management, and 41 of 91 respondents to the present survey selected 0.2% NS. A randomized controlled study by Yung and Keeley

3) found that postoperatively, children can show greater declines in plasma sodium concentration than adult patients, and thus need to be treated with isotonic salines. The textbooks also recommend that surgical patients should receive isotonic fluids at least 6 to 8 hours postoperatively

6). A significant majority of respondents prescribed a hypotonic saline for postoperative management, which can increase the risk of iatrogenic hyponatremia.

In the fourth scenario, that which required selection of a fluid for initial hydration of an infant with dehydration, the majority of respondents (96.7%) selected isotonic fluids. In fact, isotonic fluid is uniformly recommended by the textbooks, and in previous reports, as the initial fluid of choice for treatment of dehydration

3,

6,

7,

9). In a prospective randomized study, Neville et al.

5) determined that isotonic fluid is better than hypotonic saline for intravenous rehydration of children with gastroenteritis, which conclusion is supported by later studies

4,

9).

Discussion

With a simple questionnaire, we assessed the maintenance-fluid prescription choices of pediatric trainees. Whereas most of the respondents chose isotonic fluid for initial hydration, in most of the other situations, 0.2% NS was selected far more commonly than 0.45% or 0.9% NS. The traditional sodium content of maintenance fluid was 20.30 mEq/L, equivalent to 0.2% NS. However, this practice had incurred hospital-acquired hyponatremia in many reported cases, resulting in morbidity and even mortality, and prompting calls for review of clinical practices in fluid therapy

10-

12). The conventional hypotonic fluid prescription for children was established before recognition of the significant potential for stimulation of arginine-vasopressin (AVP) production in most hospitalized patients

11). Common conditions such as pain, stress, starvation, fever, and surgery, as well as lung or central nervous system disease, are now known to stimulate AVP production

11,

13). Hypotonic fluid administration in the presence of elevated AVP levels results in a sharp fall in the serum sodium level, whereas isotonic fluids effectively prevent it

2,

9,

11,

14). Several prospective studies, moreover, have supported the hypothesis that 0.9% NaCl is an effective prophylaxis against hyponatremia

3,

4).

The four clinical scenarios presented in the survey were all examples of the above-noted AVP-excess conditions

9,

14). Ill children can have multiple nonosmotic triggers for AVP secretion

11). Among the 1,057 children admitted to the pediatric emergency room of Seoul National University Children's Hospital in 2006, excluding those with underlying diseases involving unstable electrolyte control such as chronic kidney disease, Bartters syndrome or other tubulopathy, 229 (21.7%) showed hyponatremia (unpublished data). Moreover, whereas the brain develops to the adult size by the age of six, the skull does not catch up until adolescence

15). Such a high brain-to-intracranial-volume ratio increases the risk of encephalopathy, which is to say that children can develop encephalopathy with relatively milder hyponatremia

8). In this light, practitioners should be mindful that severe hyponatremia can occur in cases where hypotonic fluids are prescribed. Current pediatrics textbooks recommend higher than 0.2% sodium contents for patients who might be producing AVP owing to volume depletion or mechanisms such as stress, pain, nausea, or respiratory disease

6,

7). However, the present survey results showed that a substantial proportion of Korean pediatric residents would routinely select hypotonic fluids in cases of common disease; furthermore, there were no considerable differences among the grades in training, which fact added weight to the necessity of up-to-date education. Freeman et al.'s

16) 2012 survey of U.S. pediatric residents revealed a tendency to prescribe hypotonic fluids, though there was increasing awareness of the rationale for isotonic fluids. And in fact, residents who were aware of the fluid prescription controversy were twice as likely to select isotonic fluids as their colleagues who were not. To narrow the gap between academic debate and practical fluid management, programmed education and effective guidelines are necessary.

In many cases, "routine" maintenance fluid, simply, is chosen for every patient, without giving the matter much consideration. In a pediatric ward, the default fluid often is an NAK3 or SD 1:4, both of which are 0.2% NS. However, 0.2% NS can be too hypotonic; and indeed, with 0.2% NS, all four of the scenarios presented in our survey might show significant hyponatremia. Therefore, before intravenous fluid is prescribed, it needs to be considered whether such administration really is necessary for the patient; and, if necessary, the electrolyte concentration of the fluid, as well as the rate and amount of fluid administration, must be carefully determined. In fact, in many cases, intravenous fluid administration is not necessary provided that the patient has a sense of thirst and access to water. Notwithstanding, fluid therapy is the cornerstone of recuperation in all critically ill patients. It should be noted that isotonic fluid is less dangerous to most children than hypotonic fluid. In any event, it is critical to monitor a patient's electrolytes once intravenous fluid administration has been initiated. The overall findings of our survey suggest that current advances in fluid management have limited reach and application in the resident training environments and that they need to be emphasized and imparted, especially to front-line practitioners. We hope that the present work will alert clinicians and primary medical practitioners to the need for programmed education and updated clinical practice guidelines on intravenous fluid prescription.