Introduction

Hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) is one of the most common causes of acute renal failure in childhood and the primary diagnosis for up to 4.5% of children on chronic renal replacement therapy1). Serotype O157:H7 is the predominant bacterial strain identified; more than 100 other Shiga toxin-producing enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli (EHEC) subtypes have also been isolated2). The reservoir of this organism is the intestinal tract of domestic animals, and it is usually transmitted by undercooked meat or unpasteurized milk. The typical manifestations of HUS are microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal insufficiency following acute hemorrhagic enteritis by EHEC. In typical HUS, more serious manifestations by EHEC include severe hemorrhagic colitis, bowel necrosis and perforation, rectal prolapse, peritonitis, and intussusceptions3,4). In this paper, we report a case of Shiga toxin-associated typical HUS complicated by small intestinal perforation with refractory peritonitis, possibly due to ischemic enteritis.

Case report

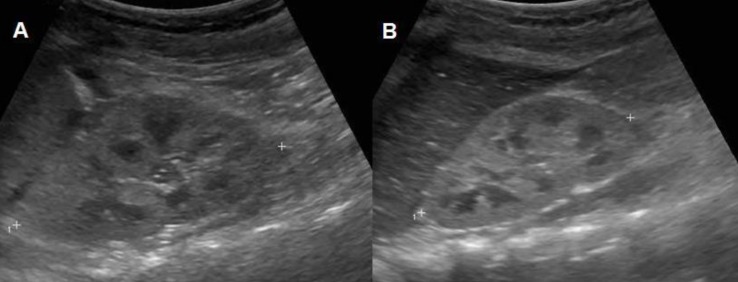

A 26-month-old female patient visited a hospital due to prolonged vomiting, poor oral intake and watery diarrhea for 5 days after eating a slushy. At the time of the visit, she was drowsy. Laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and azotemia. Renal ultrasonography revealed diffusely increased parenchymal echogenicity with decreased perfusion in both kidneys (Fig. 1). Despite supportive care, her azotemia worsened; therefore, two days later, (the 3rd hospital day), acute peritoneal dialysis (PD) was started. On the 6th hospital day, when she was transferred to another hospital, her dialysate looked bloody. On the next day (the 7th hospital day), she presented with abdominal tenderness and leukocytosis of her peritoneal dialysate (1,140/mm3). Subsequently, the intraperitoneal antibiotic administration of cefazolin and ceftazidime was initiated. However, azotemia and leukocytosis of the peritoneal fluid persisted; thus, on the 9th hospital day, the patient was transferred to Seoul National University Children's Hospital for further management.

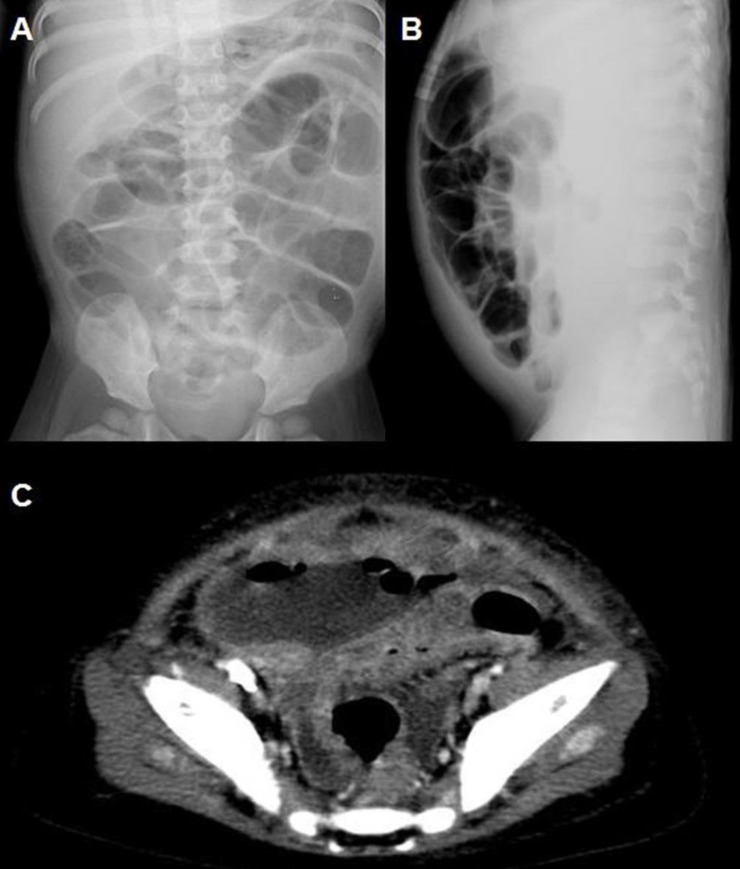

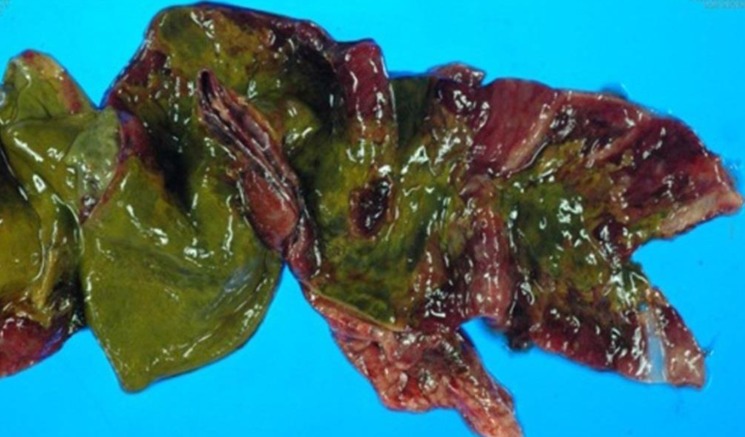

At our hospital, the patient was alert but appeared acutely ill. She was not feverish. Upon physical examination, her whole abdomen was tender, and mild pitting edema was present. Laboratory tests revealed a leukocyte count (white blood cell, WBC) of 60,960/µL; hemoglobin (Hb) level, 9.4 g/dL; hematocrit (Hct), 28.4%; reticulocyte count (Reti), 10.62%; platelet count (Plt), 24,000/µL; serum sodium (Na) level, 139 mmol/L; serum potassium (K) level, 3.4 mmol/L; serum chloride level, 106 mmol/L; total carbon dioxide level, 20 mmol/L; serum blood urea nitrogen/creatinine level (BUN/Cr), 109/4.8 mg/dL; and C-reactive protein, 5.37 mg/dL. Schistocytes were observed on peripheral blood smear. Shiga toxin was detected from stool sample by polymerase chain reaction of Shiga toxin gene. WBC and red blood cell count of the peritoneal dialysate were 4,600/µL (polymorphonucleocyte, 98%) and 9,800/µL, respectively. The peritoneal dialysate culture revealed Enterococcus species, which were resistant to ampicillin and sensitive to vancomycin; accordingly, cefazolin was switched to intraperitoneal vancomycin. However, her peritonitis did not improve; therefore, the PD catheter was removed on the 12th hospital day, and hemodialysis (HD) was started. Three days later (on the 15th hospital day), severe ileus developed with aggravated abdominal tenderness. An exploratory laparotomy was performed under the suspicion of intestinal perforation (Fig. 2), and a 15 cm long intestinal necrotic change from the terminal ileum to the cecum with small perforation of the terminal ileum was found. She underwent an ileocecectomy with double-barrel ileostomy (Fig. 3). Pathologic evaluation revealed segmental transmural necrosis with perforation, transmural hemorrhage and hyaline thrombi in the small arteriole and vein. After the operation, her general condition and laboratory findings improved. HD was discontinued on the 20th hospital day, and she was discharged on the 54th hospital day. At discharge, laboratory findings revealed a WBC count of 15,380/µL; Hb, 8.6 g/dL; Hct, 26.2%; Reti, 4.8%; Plt, 516,000/µL; and BUN/Cr, 12/0.6 mg/dL. The ileostomy was repaired one month after discharge, and she has been doing fairly well without specific complications. Laboratory findings at three years after discharge revealed a WBC count of 8,310/µL; Hb, 11.7 g/dL; Hct, 25.3%; Plt, 331,000/µL; and BUN/Cr, 16/0.56 mg/dL.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a Korean pediatric patient with intestinal perforation complicating Shiga toxin-associated (typical) HUS. While the degree of renal damage is of utmost concern in HUS, the case presented here shows that extrarenal complications also need to be considered in severe cases. In fact, the mortality in HUS is reported to be 3%-5% and is commonly associated with severe extrarenal disease, such as severe central nervous system involvement and severe colitis1,5). HUS colitis may persist for one to eight weeks5,6) due to the toxic effect of Shiga toxin (verotoxin) on endothelial cells6) and the induction of apoptosis in mucosal epithelial cells7,8).

The incidence of colonic perforation in HUS has been reported to be up to 1%-2%2). According to the literature, the transverse or descending colon is perforated 6.5 to 12 days after the onset of HUS symptoms in patients of one to five years of age3,9,10). Interestingly, the perforation site was the small intestine in our patient. We speculated that the refractory peritonitis of this patient was due to the perforation of the intestine, although it was confirmed only after a computed tomography scan performed on the 17th day after the onset of HUS symptoms. Because the small bowel involvement is very rare in a patient with HUS6), other more common causes should also be considered in this case, such as complication of intussusception or mechanical perforation during PD catheter insertion. While no definitive conclusion could be drawn in this case due to insufficient evidence, we reckon that underlying condition of typical HUS would have precipitated bowel perforation, by providing focal lesion of intramural vasculitis, the leading point, susceptible to intussusception, or lowering the resilience of intestinal wall during procedure.

Because most children with HUS have abdominal pain and tenderness, abdominal symptoms of perforation are difficult to differentiate from the uncomplicated colitis of HUS. It is helpful to know that colonic perforation rarely occurs within the first week of the disease but instead much later9). In severe HUS, indications of surgical exploration include toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, acidosis unresponsive to dialysis, or recurrent signs of obstruction or colonic stricture11,12); Therefore, it is important to keep in mind the possibility of intestinal perforation when the gastrointestinal symptoms of patients with HUS do not improve. In these cases, prompt surgical exploration is necessary.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation