Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 58(10); 2015 |

|

Abstract

Purpose

Croup is a common pediatric respiratory illness with symptoms of varying severity. Moreover, epiglottitis is a rare disease that can rapidly progress to life-threatening airway obstruction. Although the clinical course and treatments differ between croup and epiglottitis, they are difficult to differentiate on presentation. We aimed to compare the clinical characteristics of croup and epiglottitis in Emergency Department patients.

Methods

The 2012 National Emergency Department Information System database of 146 Korean Emergency Departments was used to investigate patients aged ≤18 years presenting with croup or epiglottitis.

Results

We analyzed 19,374 croup patients and 236 epiglottitis patients. The male:female sex ratios were 1.9:1 and 2.3:1 and mean ages were 2.2±2.0 and 5.6±5.8 years, respectively. The peak incidence of croup was observed in July and that of epiglottitis was observed in May. The hospitalization rate was lower in croup than in epiglottitis patients, and the proportion of patients treated in the intensive care unit was lower among croup patients. The 3 most common chief complaints in both croup and epiglottitis patients were cough, fever, and dyspnea. Epiglottitis patients experienced dyspnea, sore throat, and vomiting more often than croup patients (P<0.05).

Conclusion

Both groups had similar sex ratios, arrival times, 3 most common chief complaints, and 5 most common comorbidities. Epiglottitis patients had a lower incidence rate, higher mean age of onset, and higher hospitalization rate and experienced dyspnea, sore throat, and vomiting more often than croup patients. Our results may help in the differential diagnosis of croup and epiglottitis.

Croup is one of the common pediatric respiratory illnesses, characterized by varying degrees of inspiratory stridor, barking cough, and hoarseness due to obstruction in the region of the larynx1,2). Although most children with croup experience a mild and short-lived illness, significant upper airway obstruction, respiratory distress, and death can occur. Croup is one of the most common reasons for children to present to the Emergency Department (ED)3). The disease mainly affects children between 6 months and 3 years old, with a peak annual incidence of nearly 5% in the second year of life4,5). Although rare, adolescents and adults can also develop croup symptoms6). The symptoms of croup result from upper airway obstruction caused by an acute viral infection, most typically from the parainfluenza virus7).

Epiglottitis is an inflammatory condition of the epiglottis and its adjacent structures that can progress rapidly to life-threatening airway obstruction8). Epiglottitis may be caused by a number of bacterial, viral, or fungal pathogens. Epiglottitis is a rare and primarily pediatric disease. In the United States (US), prior to the availability of Haemophilus influenzae serotype b vaccines, the annual rate of epiglottitis was approximately 5 per 100,000 children younger than 5 years old9). Most cases of epiglottitis in otherwise healthy pediatric patients are caused by H. influenzae type b10). The age of patients with epiglottitis has increased due to decreased incidence of epiglottitis in children after the introduction of the conjugate H. influenzae serotype b vaccine10). Without treatment, epiglottitis can progress to life-threatening airway obstruction.

Croup and epiglottitis in children can easily be confused11). Early recognition of epiglottitis is vital to avoid misdiagnosis and life-threatening acute airway obstruction and peripheral circulatory failure12).

Herein we describe clinical characteristics of children and adolescents brought to an ED in Korea in 2012 with croup or epiglottitis. We compared cases, based on the assumption that the diseases' epidemiologic features were different, to help accurately diagnose croup and epiglottitis at ED presentation.

A retrospective cross-sectional study of ED reports was performed using data compiled from the 2012 National Emergency Department Information System (NEDIS) database. The NEDIS is a Korean national information system, conducted by the National Emergency Medical Center since 2004. We limited the study to data collected between January 2012 and December 2012 from children and adolescents <19 years old with a KCD-6 (Korean Classification of Diseases, sixth revision) code of J05.0 (croup) or J05.1 (epiglottitis).

Patient record forms that collected standard data were the survey instrument. Data from 146 EDs (21 regional emergency centers, 2 specialized emergency centers, 113 local emergency centers, and 10 local emergency institutes) were collected from the NEDIS in 2012. Because these surveys did not track individual patients, the NEDIS data represented a proportion of visits, not necessarily individual patients. Demographic data such as age and sex were included. Clinical characteristics included up to 8 diagnoses (coded using the KCD-6), up to 3 chief complaints for the visit, time of visit, day of onset, and outcome of treatment in the ED.

An exemption from informed consent for study participation was granted from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University College of Medicine/Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea as this was a retrospective study with no identifying data.

The statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). The chi-square test was used to assess differences in the chief complaints and the comorbidities between the croup and epiglottitis groups. Statistical significance was defined as P<0.05.

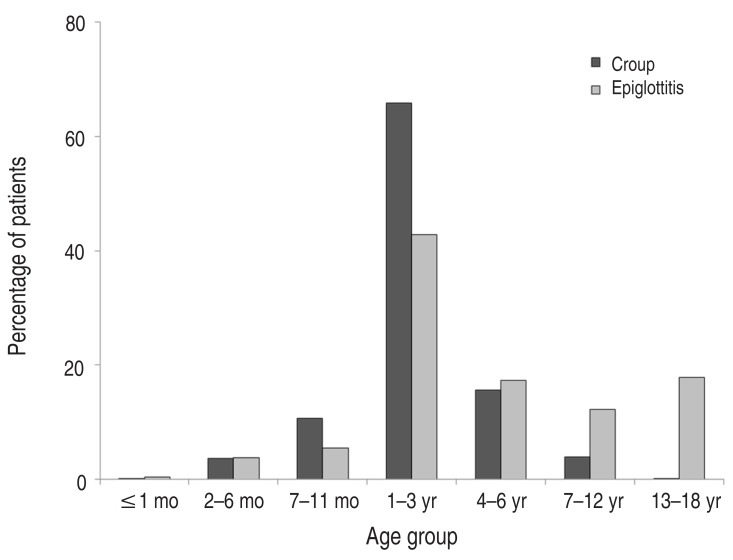

In this study, there were 19,374 ED reports of children and adolescents with croup. The male:female (M:F) ratio was 1.9:1. The mean age was 2.2±2.0 years. The peak age group was 1 to 3 years. There were 236 ED reports of children and adolescents with epiglottitis. The M:F ratio was 2.3:1, and the mean age was 5.6±5.8 years. The peak age group was also 1 to 3 years (Fig. 1). The incidence of croup gradually decreased with age in patients older than 4 years. In contrast, the incidence of epiglottitis did not decrease with age in patients older than 4 years.

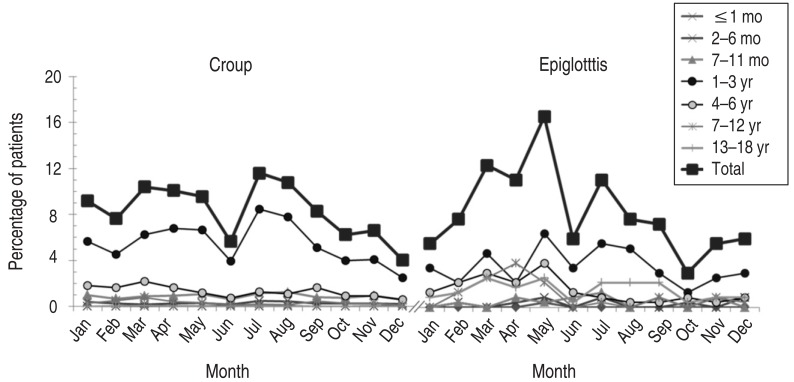

The month with the highest incidence of croup was July (11.6% of all ED visits). August, March, and April had the next highest incidences (10.8%, 10.4%, and 10.1%, respectively). A peak incidence in patients less than 3 years old was observed in July, while a peak incidence in patients older than 4 years was observed in March. A peak monthly incidence of epiglottitis was observed in May (16.7%) in all age groups, followed by decreasing incidences in March, April, and July (12.4%, 11.1%, and 11.0%, respectively) (Fig. 2). Parainfluenza virus detection and croup incidence shared a peak in July and August (Fig. 3).

The hospitalization rate of children and adolescents with croup was 22.8%, and 0.6% of them were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). The highest admission rate, 51.5%, was seen in patients less than 1 month old. The admission rate of children and adolescents with epiglottitis was 39.8%, and 6.4% of them were admitted to the ICU. The highest ICU admission per hospitalization rates were seen in patients less than 1 year old (28.6% and 12.5% in the 2 to 6 month and 7 to 11 month age groups, respectively) (Table 1). Children and adolescents with epiglottitis showed a higher ICU admission rate than those with croup (epiglottitis, 6.4%; croup, 0.6%; P<0.01). There was 1 report of mortality among children and adolescents with croup and no mortality reports in the epiglottitis group.

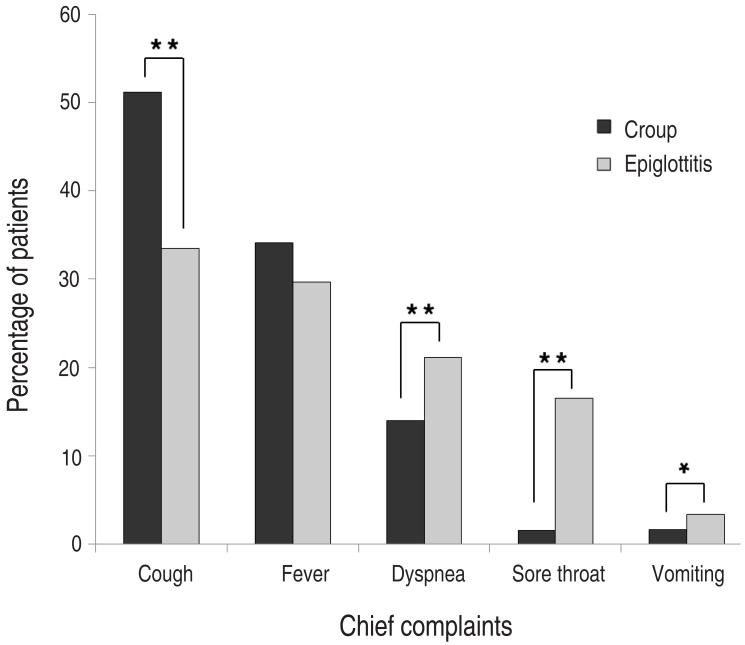

The 3 most common chief complaints in children and adolescents with croup or epiglottitis, in order of occurrence, were cough, fever, and dyspnea. Children and adolescents with croup complained more of cough (croup, 51.2%; epiglottitis, 33.5%; P<0.01), while those with epiglottitis complained more commonly of dyspnea, sore throat, and vomiting (dyspnea, 14.0% vs. 21.2%, P<0.01; sore throat, 1.6% vs. 16.5%, P<0.01; vomiting, 1.6% vs. 3.4%, P=0.03). In particular, children and adolescents with epiglottitis complained of sore throat nearly 10 times more often than those with croup (Fig. 4).

The peak time of arrival to the ED was from midnight to 3 AM in the croup group (28.2%) and epiglottitis group (22.0%). Additionally, visits of children and adolescents with either croup or epiglottitis were more infrequent during the day than at night (Fig. 5).

The 5 most common croup comorbidities were upper respiratory infection (URI) (10.6%), pneumonia (7.2%), bronchitis (6.6%), bronchiolitis (3.8%), and asthma (3.5%). Of children and adolescents who were diagnosed with croup, 0.3% of them were also diagnosed with epiglottitis. The 5 most common epiglottitis comorbidities were also URI (19.9%), pneumonia (8.1%), bronchitis (5.1%), bronchiolitis (5.1%), and asthma (2.5%) (Table 2). Epiglottitis was accompanied by URI more often than croup (epiglottitis, 19.9%; croup, 10.6%; P<0.01).

In this study, we described clinical characteristics of children and adolescents with croup or epiglottitis brought to 146 EDs in Korea. As illustrated in Fig. 1, there were nearly 100 times more ED reports of children and adolescents with croup than with epiglottitis (19,374 vs. 236). The mean age of patients with epiglottitis was higher than that of the croup group. Croup and epiglottitis share the same 3 chief complaints of cough, fever, and dyspnea, in the same order, although ED reports of children and adolescents with epiglottitis showed higher frequencies of dyspnea, sore throat, and vomiting than those with croup.

Croup is a common pediatric respiratory illness. While croup has clinical significance, epiglottitis is a rare disease that may lead to a fatal outcome, and it is difficult to differentiate between croup and epiglottitis in the early phases of illness. The difficulty is largely because both epiglottitis and croup occur in children of the same age group and cause upper airway obstruction. Additionally, young physicians may never have seen a case of epiglottitis, as the incidence of epiglottitis has decreased markedly12). Misdiagnosing epiglottitis may lead to a fatal outcome, as epiglottitis can cause a rapid onset of life-threatening airway obstruction. Delayed diagnosis of croup may also end with fatal airway obstruction and even mortality, although death from croup has become a rarity with the advent of modern techniques to support and secure the airway. Early differential diagnosis between croup and epiglottitis is thus vital.

In this study of 19,374 ED reports of children and adolescents with croup in 2012, we analyzed the distributions of age, sex, arrival time, day of onset, diagnoses, chief complaints, and outcome of visit. Our results, in accordance with previous reports, showed male dominancy with a M:F ratio of 1.9:113). The most common months of incidence were July and August. The results of this study did differ from an 11-year study (July 1964 to June 1975) in the US, in which croup season peaked in late autumn (September to December), with the highest monthly prevalence of parainfluenza viruses isolated from children with croup during the same period5). Another study in Korea corroborated a peak autumn incidence of croup. We reviewed respiratory virus distributions in 2012 from the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to assess the factors associated with the monthly distribution of croup14). The peak of parainfluenza virus detection in July and August could account for the peak of distribution of croup during the same period. The high incidence of croup from January to April may be associated with the 2012 influenza virus epidemic (Fig. 3)15). Younger age groups with croup were more likely to be hospitalized and potentially treated in the ICU than the older age groups. This suggests that younger age groups are more vulnerable to respiratory complications of croup. Similar to previous studies' results, the 3 most common chief complaints of croup were cough, fever, and dyspnea12). Children and adolescents with croup or epiglottitis visited EDs more frequently at night than during the day. Peak time of an ED visit was from midnight to 3 AM for both groups. This suggests, in accordance with previous studies, that croup symptoms become worse during nighttime hours4). Additionally, children and adolescents with croup or epiglottitis who require nighttime treatment must go to the ED, because most clinics are closed at night.

The total number of children and adolescents brought to an ED with epiglottitis was 236, a much smaller group than the 19,374 patients with croup. The actual difference in incidence between the 2 diseases may be greater, considering that most children with croup have a mild and short-lived illness that does not require emergency care. There was no significant difference in the M:F ratio between croup and epiglottitis (1.9:1 and 2.3:1, respectively). The mean age of patients in the epiglottitis group was about 2.5 times higher than that of the croup group (5.6 years and 2.2 years, respectively). Croup rarely occurred in school-aged children and adolescents. Children and adolescents with epiglottitis showed higher hospitalization and ICU admission rates than those with croup. This was probably due to the high degree of emergency and severity of epiglottitis. The 3 most common chief complaints of epiglottitis were cough, fever, and dyspnea, in contrast to other studies that found that children and adolescents with epiglottitis rarely complain of cough. In this study, the chief complaint of cough included barking cough (41.3% in croup and 40.5% in epiglottitis), contrary to previous studies saying that cough and barking cough are rare in epiglottitis16). In accordance with previous studies, the occurrence of fever showed no statistically significant difference between croup and epiglottitis (P=0.15), whereas children and adolescents with epiglottitis tended to complain of sore throat about 10 times more often than those with croup12). Children and adolescents with epiglottitis also vomited more frequently than those with croup. While previous studies have suggested that a complaint of drooling is an important factor that differentiates epiglottitis from croup, no patients with croup or epiglottitis complained of drooling in this study. This omission is likely because our data from the NEDIS consisted of up to only 3 chief complaints (mean, 1.2 complaints) and did not include all symptoms that patients may have experienced. The 5 most common comorbidities were URI, pneumonia, bronchitis, bronchiolitis, and asthma in both croup and epiglottitis. In the epiglottitis group, URI was more often diagnosed than in the croup group (P<0.01). That may be because patients with croup are known to show cough more often than those with epiglottitis13). Therefore, patients complaining of cough with croup were less likely to be diagnosed with a discrete URI compared to patients with epiglottitis.

Incidence of epiglottitis, a known but rare pediatric disease, has decreased in children and adolescents after the introduction of the conjugate H. influenzae serotype b vaccine17,18). Still, despite its low incidence in this study, epiglottitis showed a high hospitalization rate, suggesting that while the disease is rare, it is still rapid, progressive, and potentially fatal. Differential diagnosis by chief complaints remains difficult. A lateral neck radiograph may be needed in some cases to confirm the differential diagnosis between croup and epiglottitis2).

This retrospective cross-sectional study using data from NEDIS was limited in that data did not contain the presence or absence of each possible symptom, test results, or long-term prognosis. Ideally, we would have tracked each individual patient's outcome, especially for subjects with epiglottitis. Unfortunately, this was not feasible, as the NEDIS did not contain the personal identifiers that might have enabled us to track patients. Despite this limitation, the study was significant for its large size, analyzing 19,610 reports of children and adolescents from 146 EDs. There have been some small-scale studies of croup in Korea, as well as some studies comparing croup and epiglottitis in other countries; however, this study was the first large study comparing croup and epiglottitis in children and adolescents presenting to EDs in Korea. Thus, we believe that the results will be useful for developing and conducting further studies on croup and epiglottitis.

In this study, children and adolescents with croup and epiglottitis shared similar chief complaints, but children and adolescents with epiglottitis tended to complain of sore throat more often and showed lower incidence, higher mean age of onset, and more severe disease than those with croup. The authors hope that the similarities and dissimilarities observed in the study will be useful for differential diagnosis of croup and epiglottitis.

Conflicts of interest

Conflicts of interest:

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Knapp JF, Simon SD, Sharma V. Variation and trends in ED use of radiographs for asthma, bronchiolitis, and croup in children. Pediatrics 2013;132:245–252.

3. Chin R, Browne GJ, Lam LT, McCaskill ME, Fasher B, Hort J. Effectiveness of a croup clinical pathway in the management of children with croup presenting to an emergency department. J Paediatr Child Health 2002;38:382–387.

5. Denny FW, Murphy TF, Clyde WA Jr, Collier AM, Henderson FW. Croup: an 11-year study in a pediatric practice. Pediatrics 1983;71:871–876.

7. Marx A, Torok TJ, Holman RC, Clarke MJ, Anderson LJ. Pediatric hospitalizations for croup (laryngotracheobronchitis): biennial increases associated with human parainfluenza virus 1 epidemics. J Infect Dis 1997;176:1423–1427.

8. Rafei K, Lichenstein R. Airway infectious disease emergencies. Pediatr Clin North Am 2006;53:215–242.

9. Cherry JD. Epiglottitis. Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, editors. Feigin and Cherry's textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2009;:244

10. Shah RK, Roberson DW, Jones DT. Epiglottitis in the Hemophilus influenzae type B vaccine era: changing trends. Laryngoscope 2004;114:557–560.

12. Tibballs J, Watson T. Symptoms and signs differentiating croup and epiglottitis. J Paediatr Child Health 2011;47:77–82.

13. Rosychuk RJ, Klassen TP, Metes D, Voaklander DC, Senthilselvan A, Rowe BH. Croup presentations to emergency departments in Alberta, Canada: a large population-based study. Pediatr Pulmonol 2010;45:83–91.

14. Yeo CY, Lee SU, Cho YK, Jung HY, Ma JS. A clinical study on the patients with viral croup. Chonnam Med J 2006;42:187–191.

15. Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Weekly respiratory virus occurrence in 2012 [Internet]. Cheongju: Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, c2012;cited 2014 Jul 1. Available from: http://cdc.go.kr/CDC/info/CdcKrInfo0502.jsp?menuIds=HOME001-MNU1175-MNU0048-MNU0050.

16. Kim KH, Jung YG, Kim MG, Eun YG. Comparison of characteristics of acute epiglottitis according to scope classification. Korean J Bronchoesophagol 2011;17:104–107.

Fig. 1

Percentage of children and adolescents, by age group, presenting to the Emergency Department with croup or epiglottitis.

Fig. 2

Monthly variations in the percentage of children and adolescents presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) with croup or epiglottitis. Filled squares (▪) indicate the total percentage of children and adolescents presenting to the ED each month.

Fig. 3

Comparison of the monthly variations in the number of detected viruses. Filled squares (▪), which are drawn together, represent the number of children and adolescents presenting to the Emergency Department with croup each month. The number of detected viruses was obtained from the database of the Korean Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2012.

Fig. 4

The five most common chief complaints accompanying croup and epiglottitis in children and adolescents at Emergency Department presentation. *P<0.05. **P<0.01.

Fig. 5

Time trends in children and adolescents presenting to the emergency department with croup or epiglottitis. Filled squares (▪) indicate the total percentage of patients of all age groups at each time of visit.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation