Introduction

Milky nipple discharge occurs frequently in neonates and, in many cases, transpires in association with palpable breast enlargement. This benign phenomenon is linked to the infant's hormonal adaptation process in the first few months of life. In contrast, bloody nipple discharge rarely occurs in infants, and it is a rather distressing finding for both parents and consulting pediatricians. Although this symptom can be associated with breast cancer in adults, most reported cases in infants have been associated with duct ectasia and a benign process. We examined a four-month-old girl who showed bilateral bloody nipple discharge without signs of infection, engorgement, or hypertrophy.

Case report

A healthy four-month-old girl presented with a bilateral, bloody nipple discharge of three days' duration. The patient was delivered vaginally at 40+6 weeks of gestation. She weighed 3.98 kg at birth and had no apparent problems. Her history showed a hospital admission, due to culture-proven pertussis pneumonia, at age one month. She had no history of medication or of trauma to her breasts. The infant had been fed entirely on breast milk. Her mother had taken herbal medicine, to improve her breast milk production, for a 10 day period ending 2 weeks ago. The infant's familial background revealed no history of breast cancer. Her growth and development were normal.

On physical examination, both breasts appeared normal, without any signs of infection, engorgement, or hypertrophy. When the examining physician squeezed either breast, blood droplets appeared at that nipple and coagulated immediately (Fig. 1). Routine laboratory examinations and coagulation tests were normal. Hormonal studies, on such as prolactin and estradiol, were within the age-appropriate reference ranges at 7.90 ng/mL and 19.70 pg/mL, respectively. When cultured, the discharge evinced Staphylococcus epidermidis, but we thought this result a false positive, due to contamination, because the patient had no signs of infection, such as fever, erythema, or hardness or tenderness of the breast.

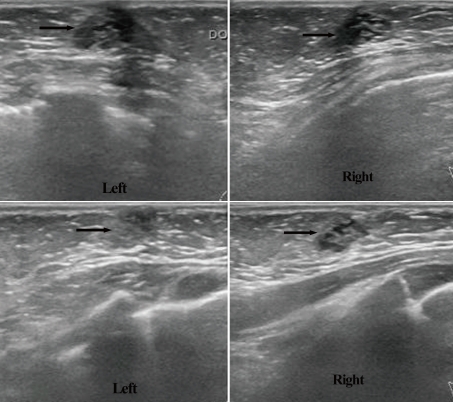

On ultrasound imaging, we observed mild duct ectasia in both breasts (Fig. 2, upper two images). We had her mother stop taking herbal medicine during breast feeding and observed the patient without any treatment, because she had no symptoms such as pain or tenderness. At her 6-week follow-up, the amount of bloody discharge was markedly diminished. Furthermore, ultrasonography showed that the duct ectasia had improved (Fig. 2, lower two images).

Discussion

Physiological breast enlargement can occur in infant girls or boys within the first few months of life. It is sometimes associated with a milky discharge. Such breast tissue hypertrophy is linked to placenta-transmitted maternal and fetal hormones1). A bloody discharge in infancy appears to be extremely rare. In 1983, Berkowitz and Inkelis first reported such bloody nipple discharges in two neonates2). At that time, they undertook no pathological examinations, however, they mentioned this clinical finding was associated with ductal hyperplasia caused by hormonal stimulation.

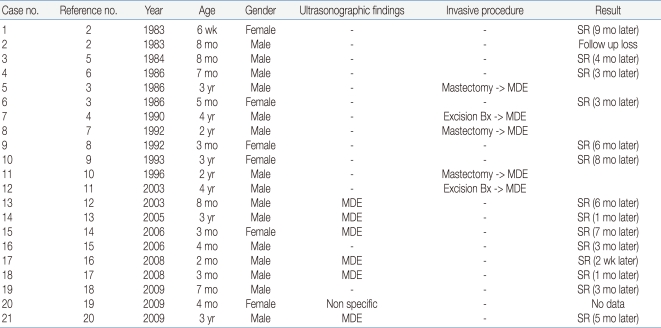

In later reports on the phenomenon, physicians recounted performing biopsies and even subcutaneous mastectomies. Then, first Stringel et al3), followed by Miller et al4), suggested mammary duct ectasia as an underlying cause, based on specimen histology. The literature reveals 21 cases of bloody nipple discharges in children under five years old2-20). Researchers performed ultrasonography in seven cases, one of which showed non-specific findings, while the other six showed mammary duct ectasia. All six patients who underwent excision biopsy or mastectomy showed mammary duct ectasia. Almost all patients who received only a watchful follow-up, without surgical treatment, had outcomes within 9 months suggesting the bloody discharge was a self-limited condition (Table 1).

Bacterial infections causing bloody nipple discharge have been reported21). In our case, Staphylococcus epidermidis was cultured. However, we thought it was likely a false positive due to contamination, because the infant had no signs of infection. There is no evidence that breast-feeding is an important variable in the etiology of this type bloody discharge, because it has appeared equally in documented accounts of breast-fed and formula-fed infants, as well as in significantly older children.

Low Dog22) reported that herbal medicine aids in the initiation, maintenance, and augmentation of milk production. Although no reports of bloody nipple discharge associated with herbal medicine appear to exist, we recommended that the infant's mother discontinue herbal medicine during breast-feeding. The symptom resolved spontaneously, without any treatment.

One major concern about bloody nipple discharge is the underlying fear of breast cancer. Researchers have reported on exceptional manifestations of breast cancer in children, such as juvenile secretory carcinoma or phyllodes tumors, in ages ranging from 20 months to 17 years23, 24). These rare tumors often present as unilateral masses that slowly progress. Bloody nipple discharge can occur due to spontaneous infarction of the tumor. Benign discharge is, in general, bilateral and not spontaneous, and it occurs with breast manipulation or stimulation, whereas pathologic discharge is usually unilateral, spontaneous, and persistent. Therefore, unilateral and bilateral discharge managements differ.

Kelly et al14) mentioned a diagnostic approach to the evaluation of bloody nipple discharges in infants. In an infant apparently experiencing bloody nipple discharge, the initial workup should include a Gram-stain; cell count and culture of the discharge; serum levels of prolactin, estradiol, and thyrotropin; and an ultrasound of the affected breast. If hormone levels are abnormal, and especially if the serum prolactin level is elevated, the patient should undergo an endocrine consultation and brain MRI, specifically to evaluate the pituitary gland.

When the culture is positive or the clinical picture suggests infection, the child requires treatment for mastitis. In our case, Staphylococcus epidermidis was cultured from the bloody discharge; however, the patient was not treated with antibiotics, because the source was thought to be contamination. If the breast ultrasound reveals a mass or abnormality other than mammary duct ectasia, the physician must evaluate the wisdom of a pediatric surgical consultation vs. watchful waiting25, 26). If patient hormone levels are within the reference range, the culture and Gram-stain are negative, and the ultrasound reveals normal breast tissue or mammary duct ectasia, we recommend a watchful waiting follow-up and reassurance for the parents.

Finally, in light of the literature case reports of a benign and self-limited process, close clinical monitoring of neonates and infants with bilateral bloody nipple discharge is advisable to avoid unnecessary, invasive investigations, such as biopsy or surgery. However, because most reported cases of mammary duct ectasia resolved within 9 months, if the discharge does not resolve in 6 to 9 months, the physician should consider a pediatric surgical consultation, regardless of other findings27, 28).

In our patient, a bloody nipple discharge was associated with mammary duct ectasia. It regressed spontaneously within 6 weeks. Although we are uncertain whether or not such maternal herbal medicine crosses to the infant and can cause a bloody nipple discharge with duct ectasia, we recommend keeping a careful check on such an infant's history, including maternal drug use, especially when the patient is a breast-fed infant.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation