Introduction

Sternal malformation/vascular dysplasia association was first described by Hersh et al.1) in 1985 but it has not yet been reported in Korea. The typical clinical features of this condition include a sterna cleft that is covered with atrophic skin, a median abdominal raphe extending from the sternal defect to the umbilicus and cutaneous craniofacial hemangiomata. This spectrum has been occasionally described as an overlap with PHACE (posterior fossa brain abnormalities, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies in the cranial vasculature, coarctation of the aorta/cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities) syndrome and hence, children with sternal malformation and hemangioma need to be evaluated for internal vascular lesions in the brain, heart, and eyes.

We report the case of an infant girl who was born with a sternal cleft and supraumbilical raphe and who developed facial hemangioma and respiratory compromise at 2 months of age.

Case report

A newborn girl was admitted for evaluation of a skin defect along the midline of her chest wall and a supraumbilical raphe. She was delivered via cesarean section at a gestational age of 39 weeks and a birth weight of 3,650 g. Her mother had previously undergone 4 pregnancies of which 1 resulted in live birth and 1 was terminated in selective abortion because of cleft palate.

At birth, the patient had a 6-cm long midline supraumbilical raphe extending from the umbilicus to the lower sternal border (Fig. 1A). Her chest wall was slightly depressed at the midsternal area (Fig. 1B). Breathing was noisy during inspiration. Chest radiograph showed no skeletal abnormalities. The abdomen and brain ultrasonograpy results were normal. Chest and abdomen computed tomographic (CT) scan showed no hemangioma or structural abnormalities. Laboratory findings were normal. Ophthalmological findings were within normal limits. At the time of presentation, we made an initial diagnosis of laryngomalacia and skin defect with raphe. Chromosome analysis showed a normal female karyotype (46, XX) and there was no evidence of mosaicism for numerical or structural rearrangement of the genes.

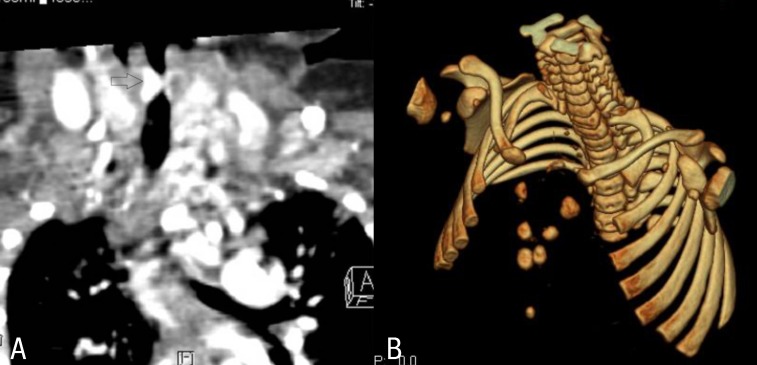

At 7 weeks, the patient was admitted to the hospital due to respiratory difficulty. Three days before admission, she developed cough and rhinorrhea but not fever. She had a severely retracted chest wall. Stridor was heard on auscultation during inspiration. Physical examination revealed multiple hemangiomas on her chin and the midline of her upper chest wall, which had developed 4weeks after birth and had gradually enlarged (Fig. 2A). The chest wall was depressed above the sternal area with a well-healed depigmented scar (Fig. 2B). With the exception of respiratory acidosis on arterial blood gas analysis, all laboratory findings were within normal range. Chest radiographs showed no abnormal lung lesion. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for close monitoring. Initial treatment included supplemental oxygen and inhaled corticosteroid. Additional therapy with intravenous dexamethasone (0.5 mg/kg/day) was administered. On the second day of hospitalization, dyspnea and stridor were improved and the vital signs ware stable. An upper respiratory tract CT scan revealed a 7 mm├Ś3 mm├Ś6.5 mm-sized hemangioma at the right lateroposterior aspect of infraglottic airway which resulted in airway constriction, and a 25 mm├Ś10 mm├Ś45 mm-sized hemangioma at the subcutaneous and cutaneous layer of the defective portion of the sternum with duplicated ossification (Fig. 3A, B). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans showed no specific abnormalities. Echocardiography findings were also found to be normal. Ophthalmological evaluation revealed no abnormalities. The patient was discharged from the hospital on the seventh day. Her symptoms were controlled by oral prednisolone treatment. No respiratory distress has been recurred during the 3 years follow-up to date.

Discussion

Sternal defect is a rare congenital malformation that more commonly presents as an isolated defect but in usual case is associated with other abnormalities. The term 'sternal malformation/vascular dysplasia association' was first proposed by Hersh et al.1) in 1985, and was used to describe the unusual association of sternal cleft with superficial craniofacial vascular lesions. The typical clinical features include a sternal cleft that is covered with atrophic skin, a median abdominal raphe extending from the sternal defect to the umbilicus, and cutaneous craniofacial hemangiomas2).

Additionally, a sternal defect may also be associated with vascular malformations on internal organs such as the respiratory tract and viscera. Among the 17 patients described by Hersh et al.1), 15 had hemangiomas in cutaneous structures, 1 in one the upper respiratory tract, and 1 had multiple hemangiomas in the mucosa of the small bowel, mesentery, and pancreas. Abnormalities that are occationally observed in association with a sternal defect include the absence of anterior pericardium, cleft lip and palate, bifid uvula, micrognathia, and glossoptosis2,3). Infantile hemangiomas are proliferative lesions consisting of aberrant localized growth of capillary endothelium.

An overlap exists between this disorder and PHACE syndrome, a term that refers to the association of posterior fossa brain abnormalities, hemangiomas, arterial anomalies in the cranial vasculature, coarctation of the aorta/cardiac defects, and eye abnormalities2). Today many experts suggest sternal malformation/vascular dysplasia association and PHACE syndrome are a single spectrum of anomalies and also classify these cases as PHACE syndrome4-6).

Although the etiology and pathogenesis of sternal malformation/vascular dysplasia association and PHACE syndrome are unknown, several mechanisms have been suggested. Any disturbance that affects the midline mesodermal structures during gestation can lead to incomplete fusion of lateral sternal bands and overlying cutaneous tissue, or deficient formation of a medioventral unpaired structure which may be involved in sternum formation during the sixth to tenth gestational weeks1,7,8). In this process, a developmental field defect may involve the upper abdominal midline, and persistence and proliferation of midline angioblastic tissue may be possible. The inheritance pattern of this syndrome seems to be sporadic. However, the baby aborted in previous pregnancy of our patient's parents had had cleft palate suggests this syndrome might be associated with a genetic factor. In addition, this syndrome has a marked female predilection of 87% to 100%9, 10). All previously reported patients were females who had either craniofacial and/or multiple hemangiomas4). The predominance of the female gender had led to speculate that PHACE syndrome might represent an X-linked dominant condition with lethality in males9). Although the homeobox (HOX), Eph genes, and ephrin proteins are suggested in association to this dysmorphogenesis, further studies are needed to confirm the contribution of specific gene defects11).

Most hemangiomas in this syndrome are superficial, plaque-like, and segmental, initially involving the face, ears, neck and upper trunk, and then grow in early infancy with appearance of mixed or deep hemangiomas. A prospective study of infantile hemangiomas described 2.3% of children with hemangiomas were PHACE patients, and approximately 20% of those with segmental hemangiomas of the face were PHACE patients11). And it was noted that there was a strong correlation between hemangiomas located over the upper half of the face and structural brain, cerebrovascular, and ocular anomalies. In contrast, hemangiomas in a mandibular distribution were associated with sternal defects and/or supraumbilical raphe11).

A significant morbidity is related to complicated and enlarged hemangioma. Abnormal vascular structures of respiratory tract may lead to respiratory compromise as in our patient. In addition, rapid expansion of the vascular lesion leads to tissue hypoxia and necrosis, which cause other complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding and infection2). Therefore, the presence of this association must signal the necessity of further evaluation for potentially life-threatening internal hemangiomas1). However, cutaneous hemangiomas do not appear at birth but develop in early infancy, usually 4 to 6 weeks after bith. Initial presentation of our patient with supraumbilical raphe, who was otherwise healthy without other cutaneous stigmata, suggested the diagnosis of isolated congenital sternal malformation. However, cutaneous and subglottic hemangiomas developed later and enlarged. Only after appearance of hemangiomas she was consistent with the diagnosis of PHACE syndrome. Although large craniofacial hemangiomas have been associated with extracutaneous hemangiomas, there seems to be no apparent correlation between cutaneous hemangiomas and the severity of the internal vascular abnormalities9,10).

Therefore, an infant with supraumbilical raphe need to follow up closely for subsequent development of internal and external hemangiomas, which may lead to life threatening events such as potential airway compromise and unexpected internal hemorrhage. And, further evaluations are necessary to find other related malformations of the brain, eyes, heart and great arteries. Recommended tests include MRI to rule out posterior fossa defects and intracranial vascular anomalies; cardiac examination including blood pressure in all extremities to rule out aortic coarctation; and ophthalmologic examination to rule out ocular abnormalities. As clinically indicated, laryngoscopy can be performed by otolaryngologist6). In conclusion, further clinical and radiological investigations have to be performed to minimize the long term complications. A high index of suspicion for sternal malformation/vascular dysplasia association and PHACE syndrome is needed in a newborn with cutaneous hemangioma and sternal cleft.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation