Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 60(6); 2017 |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of lamotrigine for the treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms in children with epilepsy.

Methods

Pediatric patients newly diagnosed with epilepsy (n=90 [61 boys and 29 girls]; mean age, 9.1±3.4 years) were enrolled. All patients were evaluated with the Korean ADHD rating scale (K-ARS)-IV before treatment with lamotrigine and after doses had been administered. The mean interval of ADHD testing was approximately 12.3 months. The initial dosage of lamotrigine was 1 mg/kg/day (maximum 25 mg/day for the first 2 weeks), and increased by 1 mg/kg every 2 weeks until titrated up to 7 mg/kg/day (or maximum 200 mg/day).

Results

The mean ADHD test score of the 90 subjects was 17.0±1.8 at baseline. It was slightly reduced to 15.6±1.7 after lamotrigine monotherapy (P >0.01). Prior to treatment, a total of 31 patients (34.4%) met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision, Of these 31 patients, 27 (87.1%) had significantly improved ADHD scores with lamotrigine monotherapy (28.0±1.6 reduced to 18.1±2.6, P<0.001). Among these 27 patients, 25 (92.6%) showed normalized electroencephalogram (EEG) and 26 (96.3%) achieved total freedom from seizures within 12 months of the initiation of lamotrigine monotherapy.

Conclusion

The results from our study show that lamotrigine had a positive effect in pediatric epilepsy patients by reducing ADHD symptoms, preventing seizures, and normalizing EEG. However, further research is required to determine whether lamotrigine is efficacious against ADHD symptoms independent of its effects on epileptic seizures.

Epilepsy is the most common childhood neurological disorder. With improvements in the quality of life of children with epilepsy due to increased therapeutic success, the recent trend in epileptic treatment is expansion of the scope of treatment from complete control of epileptic seizures to the prevention and cotreatment of language impairment or behavior deficits frequently found in children with epilepsy. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), one such behavior deficit, is a relatively common disorder concomitant in 4%–9% of school-aged children, and its prevalence among children with epilepsy is reported to be 2–10 times higher1,2,3,4).

Lamotrigine, a representative anticonvulsant, is a drug used as a stimulant or sedative through its pharmacological mechanism affecting sodium and calcium channels and hence the synaptic transmission of excitatory neurotransmitters5,6,7). Lamotrigine might be a good a first-line candidate for the treatment of ADHD with epilepsy, given that stimulants capable of regulating the neurotransmitter system can positively interfere with the ADHD mechanism. Against this background, this study was conducted to determine the therapeutic response to lamotrigine in pediatric epilepsy patients with comorbid ADHD. To investigate the actual effects of lamotrigine on ADHD symptoms, we performed a retrospective study by reviewing medical records from one hospital, thereby estimating ADHD prevalence in pediatric epilepsy patients and analyzing outcome variables such as epileptic characteristics, abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) sites, abnormal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), duration of lamotrigine treatment, and responses to drug therapy.

Of the pediatric patients diagnosed with epilepsy between September 2010 and August 2014 at the pediatric neurology clinic of the Department of Pediatrics of the Chonbuk National University Children's Hospital. All the patients were treated by one pediatric neurologist (SJK). This is a retrospective chart review of prospectively collected databased on admission. We selected 101 newly diagnosed epileptic patients, who had no history of antiepileptic drug treatment and started lamotrigine monotherapy. After the exclusion of 11 patients, whose treatment was later changed to combination therapy involving other anticonvulsant drugs or whose medical records were incomplete, 90 patients (61 boys and 29 girls) were enrolled and their medical records were retrospectively compared and analyzed.

This study was performed with approval from the Institutional Review Board of Chonbuk National University Research Council (CUH 2013-07-007-001).

Lamotrigine was administered using the following 2 weekly dosage regimen, up to the maximum dose of 7 mg/kg/day (200 mg/day): 1 mg/kg/day in weeks 1 and 2; 2 mg/kg/day in weeks 3 and 4, and further increments at 2-week intervals. The maximum daily dose, once reached, was kept constant (7 mg/kg/day or 200 mg/day) and the mean dose was 5.47 mg/kg/day. ADHD symptoms were evaluated by comparing the baseline conditions with the conditions at the time point of lamotrigine titration. The mean time interval between premedication and postmedication assessment of the variables was 12.3 months (range, 9–15 months).

Diagnosis of ADHD was confirmed based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision, criteria and a questionnaire completed during interviews with patients and their parents. The questionnaire was conducted in accordance with reference standards of the Korean ADHD rating scale-IV scores. Symptoms related to inattention (odd-number items) and hyperactivity-impulsivity (even-number items) were quantified by assigning each answer a progressive score ranging from 0 to 3 points (0, not at all; 1, just a little; 2, pretty much; 3, very often)8). Patients with ADHD test scores lower than the reference standard also completed pre-post comparison of variables to verify any decrease or increase in ADHD symptoms. Among the pediatric epilepsy patients with ADHD symptoms, characteristics assessed included epileptic patterns, abnormal EEG sites, MRI images, duration of lamotrigine treatment, responses to the drug therapy, and EEG was followed up at 4 months later for confirming seizure outcome and was consecutively executed yearly.

Among the total 90 subjects, the average age was 9.1±3.4 years (range, 4–19 years) and the sex ratio was 2.1:1 (61 boys and 29 girls) (Table 1). Distribution of seizure types was 85.6% partial seizure (n=77), 13.3% generalized seizure (n=12), and 1.1% other seizure (n=1). The most common type of epilepsy and epileptic syndrome was complex partial seizure (63.4%, n=57), followed by idiopathic generalized epilepsy (11.1%, n=10), benign rolandic epilepsy (20.0%, n=18), benign occipital lobe epilepsy (2.2%, n=2), generalized epilepsy with febrile seizure plus (1.1%, n=1), juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (1.1%, n=1), and mixed type (1.1%, n=1) (Table 1).

All 90 subjects had been done EEG recordings. Focal epileptiform brainwaves were observed in 73 subjects, with abnormal areas observed in the frontal (34.5%, n=31), central (11.1%, n=10), temporal (24.5%, n=22), parietal (3.3%, n=3), and occipital (7.8%, n=7) lobes, as well as multifocal areas (4.4%, n=4). Generalized discharges were also present (4.4%, n=4), and nine patients (10.0%) showed a normal EEG (Table 1).

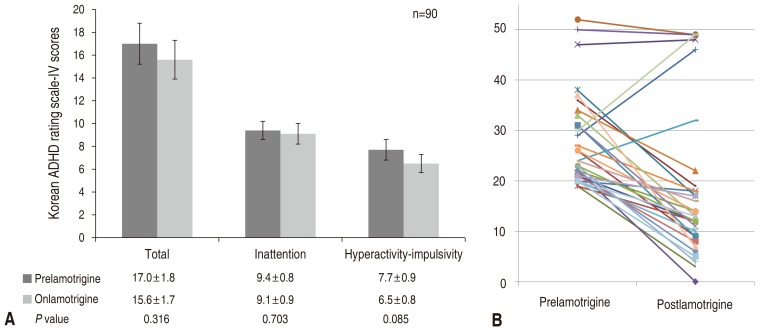

The mean ADHD test score of all 90 subjects was 17.0±1.8 at baseline. It was slightly reduced to 15.6±1.7 after lamotrigine monotherapy, but this did not reach statistical significance. Inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity scores were also slightly decreased, but this did not reach statistically significance (9.4±0.8 vs. 9.1±0.9 and 7.7±0.9 vs. 6.5±0.8, respectively, P>0.01) (Fig. 1).

We compared changes in ADHD test scores among the 90 subjects before and after lamotrigine monotherapy. The number of patients who showed decreased, increased, and unchanged posttreatment ADHD scores were 50 (55.6%), 35 (38.9%), and 5 (5.6%), respectively.

The mean ages of the group with decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy and increased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy were similar at 9.1±3.4 and 10.3±4.2 years, respectively. In both groups, boys outnumbered girls: in the group with decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy the male: female ratio was 34:16, in the group with increased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy the male:female ratio was 25:10; these differences were not statistically significant. In the group with decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy, 43 patients (86.0%) showed partial seizures, and 17 patients (34.0%) had focal epileptic discharges in the frontal lobe. Partial seizures and focal epileptic discharges in the frontal lobe were also found in 29 (82.9%) and in 12 patients (34.3%), respectively, in the group with increased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy. Interestingly, there was a considerable intergroup difference in seizure freedom rates: while only one patient (2.0%) had one or more seizure attacks during lamotrigine monotherapy treatment in the group with decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy, 13 (37.1%) continued to have seizure attacks in the group with increased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy. This confirms that the number of seizure-free patients was significantly higher in the group with decreased ADHD scores than in the group with increased ADHD scores after lamotrigine monotherapy (P<0.01) (Table 2).

The results of a comparative analysis of responses to lamotrigine monotherapy displayed by the group with increased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy and the group with decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy verified that lamotrigine is a meaningful factor for ADHD symptom regulation. The 90 subjects were divided into seizure-free and sustained seizure groups, and a detailed intergroup comparison was performed by breaking down responses to lamotrigine monotherapy into all comparable variables.

The seizure-free group included 75 patients (83.3%) who had no seizure attacks during the ADHD evaluation period between baseline and completion of lamotrigine monotherapy (the time point at which maximum dosing commenced) or during the last 6 months of follow-up observation. The remaining 15 patients (16.7 %) who had one or more seizure attacks during the same period were assigned to the sustained seizure group. The mean age of the seizure-free group was 9.4±3.5 years and that of sustained seizure group was 7.8±2.9 years, showing no statistically significant intergroup difference. In both groups, boys outnumbered girls (seizure-free group, 51 of 75 [68.0%]; sustained seizure group, 10 of 15 [66.7%]), though with no significant intergroup differences.

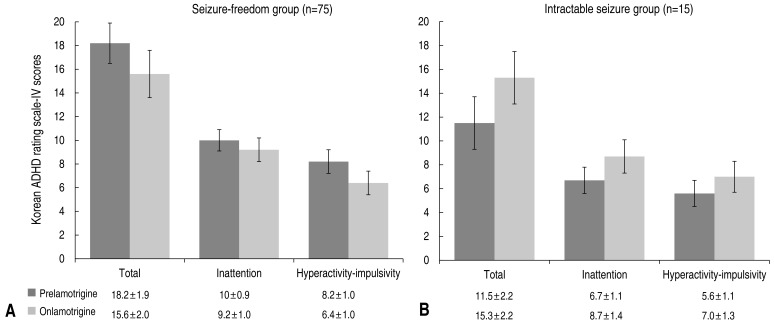

On lamotrigine monotherapy, the mean ADHD test score of the seizure-free group (n=75) decreased from 18.2±1.9 at baseline to 15.6±2.0 posttreatment. In addition, measured inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity also decreased from 10.0±0.9 to 9.2±1.0 and 8.2±1.0 to 6.4±1.0, respectively (Fig. 2). The sustained seizure group showed both an increase in the mean ADHD test score from 11.5±2.2 to 15.3±2.2, and an increase in the mean scores related to inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity (6.7±1.1 to 8.9±1.4 and 5.6±1.1 to 7.0±1.3, respectively) (Fig. 2).

Of the 90 subjects, 31 (34.4%) met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, according to the ADHD test score prior to lamotrigine monotherapy. Of these 31 patients diagnosed with ADHD prior to treatment, 27 (87.1%) achieved a decrease in ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy, thus demonstrating an improvement in ADHD symptoms. Boys were predominant (81.5%, n=22) among the 27 patients who showed decreased ADHD scores and improved ADHD symptoms posttreatment. With respect to focal epileptic discharges, 14 patients (51.9%) showed epileptic discharges in the frontal lobe, 6 patients (22.2%) in the temporal lobe, 1 patient (3.7%) in multiple lobes, and 2 patients each (7.4%) in the central and occipital regions. One patient (3.7%) showed generalized epileptic discharges. MRI scans were performed on 18 of the 27 patients with ADHD at baseline, who showed decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy; with the exception of 5 patients who showed nonspecific findings such as sinusitis, all showed normal MRI findings. Twenty-five of the 27 patients (92.6%) with decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy diagnosed with ADHD prior to therapy recovered normal brain waves within 12 months of the initiation of lamotrigine monotherapy. The remaining 2 patients (7.4%) showed improved brain waves after 12 months or no improvement. Twenty-six of the 27 ADHD patients (96.3%) who showed decreased ADHD scores on lamotrigine monotherapy achieved seizure freedom group. One patient (3.7%) belonged to the sustained seizure group.

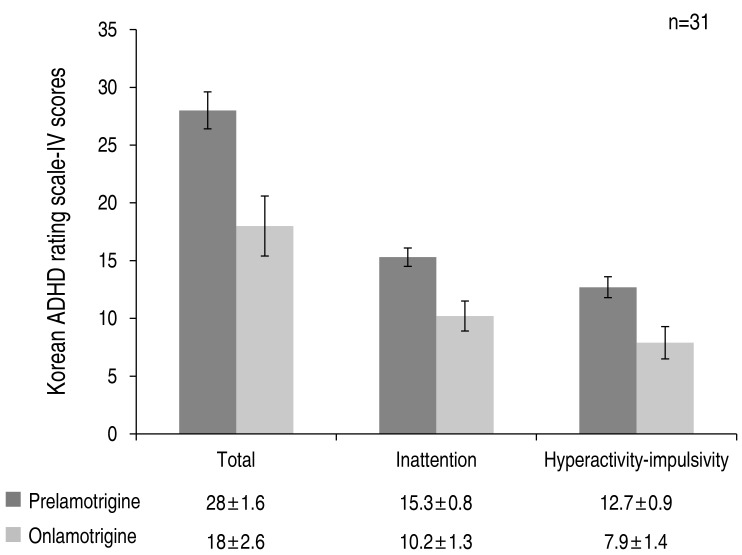

The average total ADHD test score of patients diagnosed with ADHD prior to lamotrigine monotherapy was 28.0±1.6, which was significantly reduced to 18.1±2.6 after lamotrigine monotherapy, thus demonstrating a statistically significant improvement in ADHD symptoms (P<0.001). The scores related to inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity also decreased from 15.3±0.8 and 12.7±0.9 to 10.2±1.3 and 7.9±1.4, respectively, the differences being statistically significant (P<0.001) (Fig. 3).

This study was conducted to determine the effects of lamotrigine monotherapy on ADHD symptoms in pediatric epilepsy patients with comorbid ADHD. The study results demonstrated that lamotrigine could be used in pediatric epilepsy patients without causing significant aggravation of ADHD symptoms. This is consistent with results from a study conducted by Öncü et al.9) that showed lamotrigine can be used as a safe treatment for adult patients with mood disorders, and with results from a study conducted by Uvebrant and Bauzienè that found lamotrigine improves cognitive function in epileptic patients7,10). In line with recent trends in epilepsy treatment towards improvement of quality of life, in addition to the complete control of epileptic seizures, increasing attention has been paid to ADHD symptoms in pediatric epilepsy patients that may arise from educational and sociological issues. The American Academy of Pediatrics reported that ADHD prevalence in children with epilepsy is 12%–39%, several times higher than in children in the general population10). Similarly, Choi et al.11) estimated that the prevalence of ADHD in children with epilepsy was 37.5%. In this study, 34.4% (31 of 90) of the subjects met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, which is towards the higher end within the ranges reported in previous studies2,10).

In general, boys reportedly have a higher prevalence of ADHD than girls12), ut it is also contended that ADHD occurs without gender differences13). In the current study, boys outnumbered girls by 2.1 fold (61 vs. 29), which is similar to sex ratios reported in previous studies11,12).

Lamotrigine is an anticonvulsant drug which is hypothesized to exert anticonvulsant effects by acting as a glutamate antagonist14). Lamotrigine monotherapy has been shown to be efficient in the treatment of childhood epilepsy, as reported in a study conducted by Han et al.15) among pediatric epilepsy patients in a hospital in Korea. Moreover, the efficacy of lamotrigine in ADHD patients with comorbid epilepsy was verified in a study reported by Sim et al.16). Because anticonvulsant drugs such as lamotrigine achieve their effects by regulating the inhibitory and excitatory neurotransmitters gamma-amino butyric acid and glutamate, rather than noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurotransmitters, which impair concentration and induce impulsivity and hyperactivity, the assumption that they aggravate ADHD symptoms is not theoretically founded7,15). In this study, 55.5% of subjects (50 of 90) scored lower on the ADHD questionnaire and 38.9% (35 of 90) scored higher posttreatment. Five patients (5.6%) did not show a difference in score. As the number of patients who achieved lower ADHD test scores outnumbered those whose scores increased or did not change, we may draw from the results of this study that lamotrigine does not exert adverse effects on ADHD symptoms; and also an improvement in ADHD symptoms cannot be deduced from these results. However, 87.1% (27 of 31) of patients who were diagnosed with comorbid ADHD at baseline showed decreased ADHD test scores after lamotrigine monotherapy, thus demonstrating lamotrigine-mediated improvement of ADHD symptoms.

Along with a number of reported study results that show ADHD and epilepsy are correlated, Choi et al.11) asserted that the ADHD symptoms in pediatric epilepsy patients vary considerably in response to anticonvulsant therapy, which allows early prediction of therapeutic reactions. The finding from the present study that the proportion of seizure-free patients within the group with decreased ADHD scores was as high as 98.0% (49 of 50), while 37.1% (13 of 35) within increased group (Table 1) (P<0.01). These findings support results from previous studies showing that improvement of ADHD symptoms is most closely associated with control of epilepsy. Based on reports from previous studies that epilepsy can affect cognitive function irrespective of ADHD comorbidity17), and that antiepileptic and anticonvulsant drugs could be risk factors for developmental disorders18,19), a large-scale study with pediatric epilepsy patients with comorbid ADHD symptoms is needed to determine the effects of such drugs on ADHD symptoms and their correlations with epilepsy.

With respect to the limitations of this study, we study did not include cognitive functions in design, but included pediatric epilepsy patients with comorbid ADHD symptoms, and multiple factors other than the effects of lamotrigine should have been included when evaluating improvements of ADHD symptoms. Likewise, a variety of ADHD evaluation tools and methods should be used to overcome errors that may occur in the evaluation of ADHD using interviews with caregivers. Moreover, there is a need for a large-scale study of pediatric epilepsy patients to overcome the limitations of small sample size. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature in that it verified that lamotrigine treatment in pediatric epilepsy patients does not adversely affect their ADHD symptoms, which can seriously impair educational and sociological development, and that lamotrigine is conducive to improving ADHD symptoms.

This study yielded the following findings: ADHD prevalence was higher in pediatric epilepsy patients than in nonepileptic children, and ADHD prevalence was higher in boys than in girls. Furthermore, ADHD test scores were significantly improved (P<0.01) among subjects diagnosed with ADHD at baseline. Subjects who demonstrated improved ADHD symptoms after lamotrigine monotherapy were male, had partial seizures with focal lobe EEG abnormalities, demonstrated normalization of brain waves within 12 months, and seizure freedom. Of these characteristics, the seizure-free group demonstrated statistically significant improvement in ADHD symptoms compared to the sustained seizure group, which implies that seizure control could play a similar function as anticonvulsant agents in the treatment of ADHD symptoms.

Based on our results, we conclude that lamotrigine can be recommended to pediatric epilepsy patients with comorbid ADHD symptoms. Our study show that lamotrigine has an positive association with reducing ADHD symptoms in pediatric epileptic patients probably due to achieving seizure freedom and normalizing EEG. But we could not find any clue that lamotrigine improve ADHD symptoms without seizure control.

Notes

Conflict of interest:

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Gucuyener K, Erdemoglu AK, Senol S, Serdaroglu A, Soysal S, Kockar AI. Use of methylphenidate for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with epilepsy or electroencephalographic abnormalities. J Child Neurol 2003;18:109–112.

2. Bennett-Back O, Keren A, Zelnik N. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with benign epilepsy and their siblings. Pediatr Neurol 2011;44:187–192.

3. Cohen R, Senecky Y, Shuper A, Inbar D, Chodick G, Shalev V, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity (ADHD) disorder: a population-based study. J Child Neurol 2013;28:120–123.

4. Pellock JM. The challenge of neuropsychiatric issues in pediatric epilepsy. J Child Neurol 2004;19(Suppl 1): S1–S5.

5. Morton WA, Stockton GG. Methylphenidate Abuse and psychiatric side effects. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2000;2:159–164.

6. Trimble MR, Cull C. Children of school age: the influence of antiepileptic drugs on behavior and intellect. Epilepsia 1988;29(Suppl 3): S15–S19.

7. Uvebrant P, Bauzienè R. Intractable epilepsy in children. The efficacy of lamotrigine treatment, including non-seizure-related benefits. Neuropediatrics 1994;25:284–289.

8. Park JI, Shim SH, Lee M, Jung YE, Park TW, Park SH, et al. The validities and efficiencies of Korean ADHD rating scale and Korean child behavior checklist for screening children with ADHD in the community. Psychiatry Investig 2014;11:258–265.

9. Öncü B, Er O, Çolak B, Nutt DJ. Lamotrigine for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder comorbid with mood disorders: a case series. J Psychopharmacol 2014;28:282–283.

10. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and evaluation of the child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2000;105:1158–1170.

11. Choi HY, Han JY, Kim SJ, Eom TH, Bin JH, Kim YH, et al. Characteristics of children with epilepsy and concomitant attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Korean Child Neurol Soc 2013;21:162–169.

12. Stores G, Hart J, Piran N. Inattentiveness in schoolchildren with epilepsy. Epilepsia 1978;19:169–175.

13. Hesdorffer DC, Ludvigsson P, Olafsson E, Gudmundsson G, Kjartansson O, Hauser WA. ADHD as a risk factor for incident unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:731–736.

14. Cheung H, Kamp D, Harris E. An in vitro investigation of the action of lamotrigine on neuronal voltage-activated sodium channels. Epilepsy Res 1992;13:107–112.

15. Han JH, Oh JE, Kim SJ. Clinical efficacy and safety of lamotrigine monotherapy in newly diagnosed pediatric patients with epilepsy. Korean J Pediatr 2010;53:565–569.

16. Sim GY, Son JW, Kim WS. The comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with epilepsy. J Korean Child Neurol Soc 2012;20:129–136.

17. Semrud-Clikeman M, Wical B. Components of attention in children with complex partial seizures with and without ADHD. Epilepsia 1999;40:211–215.

Fig. 1

(A) Changes in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder test scores after lamotrigine treatment in all patients. (B) Individual score changes after lamotrigine treatment. ADHD, attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder.

Fig. 2

Changes in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder test scores after lamotrigine treatment in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) confirmed patients.

Fig. 3

Changes in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder scores between seizure-free (A) and intractable-seizure (B) groups after lamotrigine treatment.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation