Article Contents

| Clin Exp Pediatr > Volume 63(9); 2020 |

|

Abstract

Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by impairments in social interaction and verbal and nonverbal communication.

Purpose

Determine the association between use of assisted reproduction technology (ART) and the risk of ASD among children.

Methods

This case-control study included 300 participants (100 cases, 200 controls). The control group included women with a child aged 2–10 years without ASD, while the cases were women with a child aged 2–10 years with ASD. We used a researcher-made questionnaire. Data were analyzed using Stata ver. 14 at the 0.05 significance level.

Results

In the univariate analysis, there was significant association between child sex, delivery mode, history of preterm delivery, history of using ART, and maternal age at child’s birth and the risk of ASD. After the adjustment for other variables, this association was significant for male sex (2.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.11–4.31; P=0.001) and history of using ART (4.03; 95% CI, 1.76–9.21; P=0.001). Therefore, after the adjustment for confounder variables, there was no significant association between ART and the risk of ASD among children (4.98; 95% CI, 0.91–27.30; P=0.065).

Graphical abstract. Assisted reproductive technology (ART) is a risk factor for autism spectrum disorders.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder defined by impairments in social interaction and verbal and nonverbal communication [1]. The prevalence of ASD has dramatically increased in the last decades. Despite much attempt to treat ASD and care system, it is still a major public health problem worldwide [2].

Recent research has reported that both genetic and environmental risk factors are effective in etiology of ASD [3]. Maternal prepregnancy obesity, preeclampsia, neonatal icterus, and low birth weight (LBW) are risk factors for ASD among children [4,5].

There is evidence that parents of children with ASD are more likely to have infertility compared with parents of children without ASD. Therefore, infertility treatments may be affected for ASD [6].

The use of assisted reproduction technology (ART) such as zygote intrafallopian transfer, gamete intrafallopian transfer, in vitro fertilization (IVF), induced ovulation, and insemination has increased in worldwide [7]. ASD and ART have similar risk factors including advanced maternal and paternal [8]. Also, ART can be leads to preterm labor and LBW, these factors are associated with ASD [9].

Fountain et al. [10] in 2015 found the association between ART and ASD greatly decreased after adjusting for the pregnancy outcomes. Therefore, this shows the importance of controlling for confounding factors. Other study by Schieve et al. [11] in 2017 in the United States (US) showed that ASD was not associated with ART or non-ART infertility treatments. Davidovitch et al. [6] reported that IVF treatment compared with spontaneous conception was not statistically significantly associated with the risk of ASD among children. However, the results of studies are inconsistent.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to determinate the association between use of ART and the risk of ASD among children through a case-control study in west of Iran.

This case-control study was conducted on 300 participants (100 cases and 200 controls) in Hamadan city for 3 months (September to November). The inclusion criteria for the control group were: women who had child without ASD and they had health records at comprehensive health centers in Hamadan city (Capital of Hamadan province). Hamadan city has a population of 651,820 people according to the national census held by the Statistical Center of Iran in 2016. There is in Hamadan city 110 children with ASD aged 2–10 years.

The inclusion criteria for the case group were: women who had child with ASD aged 2–10 years and they were recruited from the Hamadan Autism Community who had medical records in the Community. In their medical record, children with ASD were screened by The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-Chat) and were diagnosed by autism diagnostic interviewrevised (ADI-R). ADI-R is currently the most adequate and most widely used diagnostic tool for autism study [12]. These tools include questions about emotional sharing, offering and seeking comfort, social smiling, and responding to other children. The cutoff scores for social interaction, communication and language, and restricted/repetitive behaviors are 10, 8 (if verbal) or 7 (if nonverbal) and 3 [13].

They referred to autism center to receive health service for their child. In this study, all women completed the questionnaire with informed consent. This study took from September 10 to November 10, 2019. The protocol of this study was approved by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences with code 9804112799 and ethical code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1398.288.

There were a total of 110 ASD children between the ages of 2–10 years in Hamadan city. Therefore, all children with ASD between 2–10 years of age in Hamadan city were included in this study through census method. Also, in order to increase the study power, 2 healthy children aged 2–10 years were considered as control for each case. The parents of 10 children with ASD were not satisfied for participate in this study. Therefore, we included 100 cases and 200 controls in the present study.

We used a researcher-made questionnaire including: the paternal and maternal age, child's age, mother's job, parity, history of preterm labor in children aged 2–10 years, delivery type, mode of conception (medication, intrauterine insemination, IVF, and spontaneous), use of ART and cause of infertility (ovulation, unspecified, uterus, Donated oocyte, spouse, fibroma, and endometritis).

Univariable logistic regression was conducted to estimate crude association between mother and child variables and odds of ASD in child. Those with P value ≤0.2 were considered as potential significant determinants of ASD and were included in multivariable logistic regression. Bootstrapping using 1,000 bootstrap samples was used to check internal validity of multivariable model and to address the possibility of optimism. Data were analyzed using the Stata ver. 14 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) at 0.05 significance level.

A total of 100 cases and 200 controls were compared in the study. A full comparison of variables related mother and child as well as the results of univariable logistic regression analyses associated with ASD is shown in Table 1. In univariable analysis, child’s sex (boys vs. girls), type of delivery (cesarean vs. natural delivery), having history of preterm delivery, mothers with history of using ART, maternal age at child’s birth (≥35 years vs. <35 years) were potentially associated with higher odds of ASD (P value≤0.2). In this study, none of the mothers used alcohol or cigarette.

In detail, among ASD cases, 78 (78.00%) were boy while corresponding figure among control group was 53%. In other words, the odds of ASD in boys was 3.14 (95% CI, 1.82–5.44; P<0.001). Moreover, in ASD cases 62% of children were born through cesarean section compared with 44.5% in control group (odds ratio [OR], 2.03; 95% CI, 1.25–3.32; P=0.005). The proportion of preterm delivery among cases and controls was 21% and 5.5%, respectively (OR, 4.57; 95% CI, 2.1–9.92; P<0.001). The odds of ASD in child among mothers with using assisted reproduction was 8.61 folds higher (P=0.007).

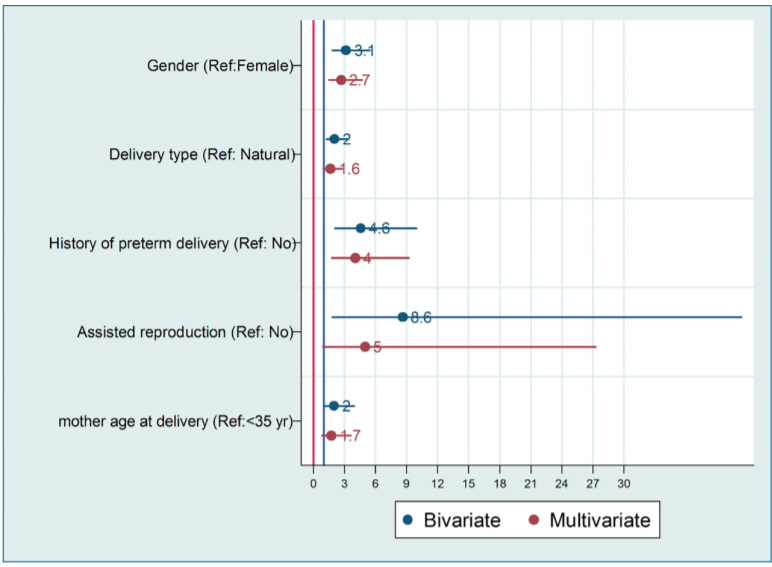

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate logistic regression. After adjusting for other variables, odds of ASD among boys was 2.66 (95% CI, 1.11–4.31; P=0.001) compared girls. Cesarean delivery was associated with 63% increase in odds of ASD (OR, 1.63; 95% CI, 0.96–2.76; P=0.07). The odds of ASD in children that their mothers had history of preterm delivery and history of using ART were 4.03 (1.76–9.21; P=0.001) and 4.98 (0.91–27.3; P=0.065), respectively. For better understanding results of crude and adjusted logistic regression is depicted in Fig. 1.

Using 1,000 bootstrap samples, it found that there were high consistency and stability between the resulting ORs (95% CIs) from the original dataset and those from the bootstrapped model.

Our findings showed that after adjusting for other variables, risk factors for ASD were boy sex and history preterm delivery for children with ASD. Therefore, after adjusting for confounder variables, there was not significant association between ART and the risk of ASD among children.

Lung et al. [8] in 2017 in Taiwan reported that ART was a potential risk factor associated with ASD in large national birth cohort study. Fountain et al. [10] in 2015 in US reported that the incidence of diagnosed ASD was twice as high for ART compared with non-ART births. The association was reduced after adjustment for demographic factors and adverse pregnancy outcomes substantially, although this association was statistically significant for mothers aged 20–34 years [10]. While, other study by Schieve et al. [11] in 2017 in US showed that ASD was not associated with ART or non-ART infertility treatments. Davidovitch et al. [6] reported that IVF treatment compared with spontaneous conception was not statistically significantly associated with the risk of ASD among children. Hvidtjørn et al. [14], in 2011 in Danish population-based study reported that children conceived using ART had an increased risk of being diagnosed with ASD; however, this association was not seen after controlling of confounder variables such as maternal age, education, parity, smoking, birth weight, and place of births. These results are consistent with the findings of our study. However, there are many potential mechanisms that ART could be associated with ASD such as the biological factors related to the underlying fertility or quality of the germ cells, effects of the fertility hormone therapies used during ART, other effects of the ART methods, and the prenatal and perinatal complications related to ART treatment [15]. Also, fetal steroid hormones during early critical periods of brain development are thought to exert an epigenetic fetal programming mechanism for autism. Progesterone affects myelination through the peripheral nervous system and the central nervous system via through mechanisms that involve both the progesterone receptor and the gamma-aminobutyric acid gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor [16]. Therefore, there was specific pathophysiology of the relationship between ASD and ART.

In a meta-analysis in 2017 by Wang et al. [17] was found an increased prevalence of ASD in children with preterm delivery (relative risk, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.16–1.48). In the present study, history of preterm delivery for children with ASD was a risk factor.

An association between advanced maternal age and ASD has been found in previous studies [9,18]. In our study, there was significant association in crude form, but it disappeared after adjusting for other variables.

There were some limitations in our study. First, in observational studies, it is possible that we did not include unmeasured demographic and parental characteristics in our study. Second, we included the income status in the questionnaire but the majority of participants did not answer to this question and this variable was omitted in the analysis. Lastly, family history in children with ASD and epilepsy was not questioned. However, these limitations can be led to bias in the results.

In conclusion, our findings showed that after adjusting for other variables, risk factors for ASD were boy sex and history preterm delivery for children with ASD. Therefore, after adjusting for confounder variables, there was not significant association between ART and the risk of ASD among children.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the Vice-chancellor of Research and Technology, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences for funding the study (research number: 9804112799). Also, we would like to thank the health staffs for their kind

collaboration.

Fig. 1.

Graphical presentation of crude and adjusted logistic regression analysis of predictors of autism spectrum disorder.

Table 1.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of predictors of ASD

Table 2.

Original and bootstrapped multivariate analyses of mother and neonate variables associated with ASD

References

1. Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders--Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ 2012;61:1–19.

2. Baxter AJ, Brugha TS, Erskine HE, Scheurer RW, Vos T, Scott JG. The epidemiology and global burden of autism spectrum disorders. Psychol Med 2015;45:601–13.

3. Bailey A, Phillips W, Rutter M. Autism: towards an integration of clinical, genetic, neuropsychological, and neurobiological perspectives. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1996;37:89–126.

4. Jenabi E, Bashirian S, Khazaei S. Association between neonatal jaundice and autism spectrum disorders among children: a meta-analysis. Clin Exp Pediatr 2020;63:8–13.

5. Jenabi E, Karami M, Khazaei S, Bashirian S. The association between preeclampsia and autism spectrum disorders among children: a metaanalysis. Korean J Pediatr 2019;62:126–30.

6. Davidovitch M, Chodick G, Shalev V, Eisenberg VH, Dan U, Reichenberg A, et al. Infertility treatments during pregnancy and the risk of autism spectrum disorder in the offspring. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2018;86:175–9.

7. Andersen AN, Goossens V, Gianaroli L, Felberbaum R, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2003. Results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1513–25.

8. Lung FW, Shu BC, Chiang TL, Lin SJ. Twin-singleton influence on infant development: a national birth cohort study. Child Care Health Dev 2009;35:409–18.

9. Idring S, Magnusson C, Lundberg M, Ek M, Rai D, Svensson AC, et al. Parental age and the risk of autism spectrum disorders: findings from a Swedish population-based cohort. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:107–15.

10. Fountain C, Zhang Y, Kissin DM, Schieve LA, Jamieson DJ, Rice C, et al. Association between assisted reproductive technology conception and autism in California, 1997-2007. Am J Public Health 2015;105:963–71.

11. Schieve LA, Drews-Botsch C, Harris S, Newschaffer C, Daniels J, DiGuiseppi C, et al. Maternal and paternal infertility disorders and treatments and autism spectrum disorder: findings from the study to explore early development. J Autism Dev Disord 2017;47:3994–4005.

12. Lampi KM, Sourander A, Gissler M, Niemelä S, Rehnström K, Pulkkinen E, et al. Brief report: validity of Finnish registry-based diagnoses of autism with the ADI-R. Acta Paediatr 2010;99:1425–8.

13. Rutter M, Le Couteur A, Lord C. Autism diagnostic interview-revised. Los Angeles (CA): Western Psychological Services, 2003.

14. Hvidtjørn D, Grove J, Schendel D, Schieve LA, Sværke C, Ernst E, et al. Risk of autism spectrum disorders in children born after assisted conception: a population-based follow-up study. J Epidemiol Community Health 2011;65:497–502.

15. Lyall K, Baker A, Hertz-Picciotto I, Walker CK. Infertility and its treatments in association with autism spectrum disorders: a review and results from the CHARGE study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2013;10:371534

16. Pluchino N, Russo M, Genazzani AR. The fetal brain: role of progesterone and allopregnanolone. Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig 2016;27:29–34. X.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation