Global and national epidemiology of PIDs

PIDs are considered rare diseases. However, with recent advances in diagnostics, increased awareness, improved care quality, and registry projects in many countries and continents, the number of identified PID patients is increasing. There are several well-established PID patient registries in America, Africa, and Europe (

Table 1) [

1-

3]. There is a movement for the development of a PID registry in the Asia-Pacific region, and Japan already has a well-established PID registry (

Table 1) [

4].

Growing evidence suggests that PID might be more common than generally thought. A study from 2013 estimated that, although there are as many as 6 million people with PID, less than 1% have been identified [

1]. There have been many attempts to estimate the epidemiology of PID in many countries with wide variability. For example, the prevalence of PID was estimated at 5.6/100,000 in Australia and New Zealand in 2007 [

5], 5.38/100,000 inhabitants in France in 2011 [

6,

7], and 1.94/100,000 in the United Kingdom in 2011 [

6,

7]. These estimates of prevalence may be lower than the actuals because these numbers were drawn from registries.

Globally, the Jeffrey Modell Foundation has established a network of physician experts on PID (Jeffrey Modell Centers Network) and performs an annual global survey. From the last survey report in 2014, as of 2013, 138,847 patients were being followed by PID expert physicians and 77,192 patients were confirmed as having PID in surveys collected from 225 centers in 78 countries in 6 continents [

6]. In 2013, there were 74.1% and 27.9% increases in the number of patients followed and those with an identified PID, respectively, compared to 2011 [

6].

In 2017, the physicians reported a total of 187,988 patients with PID, with an estimated global prevalence of 2.5 per 100,000 persons [

8,

9].

In Japan, a survey was conducted on PID patients who were alive on December 1, 2008 and those who were newly diagnosed and dead between December 1, 2007 and November 30, 2008. This study estimated the prevalence of PID as 2.3 per 100,000 persons (

Table 1) [

4].

In Korea, a study investigated the epidemiology of PID from 2001 to 2005 and identified 152 patients from 23 major hospitals [

10]. In this study, the prevalence of PID in Korea in 2005 was 1.13 per 100,000 persons. However, these numbers may have been underestimated; thus, further studies are needed.

Advancement in diagnosis and management of PID

Certain PIDs have typical presentations, but the clinical manifestations among many PIDs are variable, although they are also similar. Therefore, taking a diagnostic approach according to phenotypic classification helps clinicians greatly when faced with potential PID [

11]. Samples from PID patients are often evaluated using flow cytometry analysis. In Korea, basic lymphocyte subset analysis (T, B, NK cells, and monocytes) by flow cytometry is relatively readily available in many referral centers, whereas tests such as dihydrorhodamine to screen for chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) are currently available only in 3 centers in the nation. In addition, several other functional tests are not available in the clinical laboratories of Korean hospitals. PID patients are in urgent need of a national insurance benefit for immunology work-ups. For example, the cost for lymphocyte subset analysis is not properly reimbursed, even for patients with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) or X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), and deferred automatically in an electronic reimbursement system by the national health insurance system. However, it is reimbursed for cancer patients who undergo hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) and follow-up tests during the post-HCT period. Increased awareness is warranted among physicians in the clinical field and officers at the national health insurance review agency to increase the care benefit of PID patients at the diagnostic workup stage and during their disease follow-up period. Therefore, support and relevant health policies are needed at the government level.

Since PIDs are typical examples of single-gene inborn errors of immunity, the genetic diagnosis is crucial for the final confirmation of the disease. It is noteworthy that, according to Casanova et al. [

12], up to 49 of the 232 monogenetic etiologies (21%) of human PIDs were initially reported in single patients. With the advancement of genetic analysis technology in the next-generation sequencing era, the cumulative number of single-gene defects underlying PIDs has increased in a short period of time [

13]. However, next-generation sequencing does not analyze all of the unknown causes of underlying genetic mutations, and 15%–40% of those unknown cases are solved [

14]. Therefore, clinicians must detect clinical clues and characterize each phenotype.

Traditional management strategies of PID patients include immunoglobulin (Ig) replacement, HCT, and antimicrobial prophylaxis. Gene therapy has been also attempted in the field [

15,

16]. With advances in genetic diagnosis and basic immunology, there are opportunities for newer therapeutic options using targeted therapy at the molecular level. In 2018, the Nobel Prize was given to one of the researchers who worked on the

CTLA-4 gene [

17]. Although much attention was given to the application of

CTLA-4 for cancer treatment, PID patients with the

CTLA-4 mutation can also benefit from target therapy using

CTLA-4 Ig treatment [

18,

19]. The current Korean health insurance system was mainly designed to enable the reimbursement for common diseases with high numbers of patients such as diabetes, hypertension, or cancers. In more common diseases such as cancers, many advanced target therapies at the molecular level are being used in the clinical field in Korea. However, there are many hurdles for rare PID patients (e.g., only one patient diagnosed in Korea) who may need this type of special target therapy as well as reimbursement from the Korean government system. There should be a formal and easy to approach channel in Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) with staff designated to manage rare diseases issues to ensure efficient communication and eventually benefits for patients with rare diseases who also have the right to receive the best care possible in Korea. Therefore, there is a need to estimate the disease burden of PID in Korea and identify advanced treatment options in Korean PID patients. This is also achievable at the global level given the fact of the rarity of the diseases and PID experts constantly collaborate to provide the world cohort data in the literature [

20]; Korean patient data should be analyzed internationally to provide evidence for a therapeutic approach in Korea.

The number of physicians with advanced knowledge about PID and proper training for managing these special groups of diseases is very limited in Korea; thus, many PID patients do not obtain a timely accurate diagnosis. Constant efforts including public awareness, physician education, and cross-talk with a government agency should be made to advance PID care in Korea.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest public funder of biomedical research worldwide [

21]. NIH grants for PID were provided for 409 projects ($35,410,126) in the United States (US) in 2016 and 2017 [

22]. Among them, 2 NIH grants ($697,747) were provided for the US Immunodeficiency Network (USIDNET) in 2016 and 2017 [

23]. The USIDNET was established to advance scientific research on PID in the US [

24]. One of their main areas of focus is to assemble and maintain a registry of validated data from PID patients. The USIDNET has been continuously funded from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH since 2005. In Korea, one such project aiming to estimate the prevalence of PID was supported by a national grant from the Korea Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (KCDC), which reported the results in 2006 [

25]. However, there is no continuous ongoing PID registry funded by a national grant in Korea.

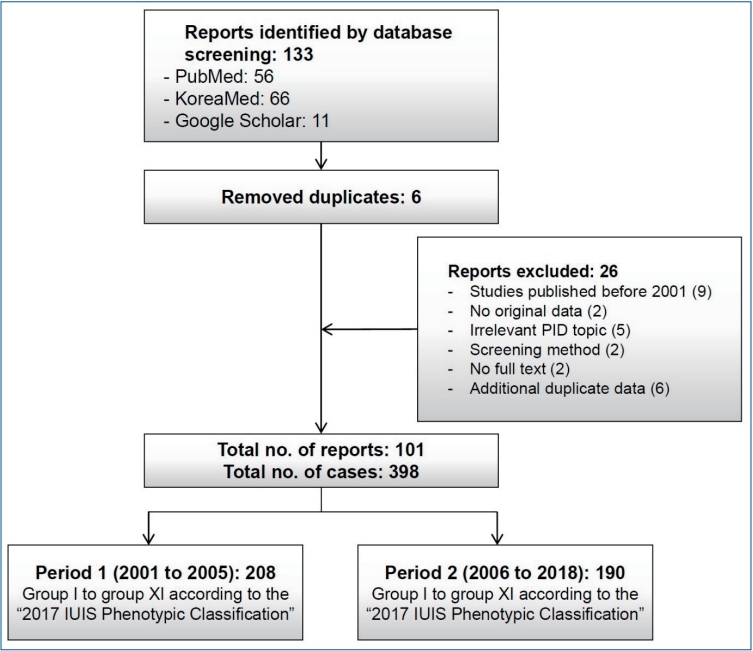

Systematic review of PID reports in Korea

All Korean or English studies on PIDs reported in a Korean or international scientific journal between January 2001 and November 2018 were identified. The International Union of Immunological Societies (IUIS) PID expert committee developed the phenotypic classification to help clinicians diagnose PID at the bedside. This report represents the most current and complete catalog of known PIDs [

11]. Thus, it serves as a reference for these conditions and provides a framework to help in the diagnostic approach to patients with suspected PID in a publication every 2 years. We searched the PubMed, KoreaMed, and Google Scholar databases for systematic reviews and checked for duplicates (

Fig. 1). The diagnosis of PID was categorized from group I to group XI according to the 2017 IUIS Phenotypic Classification. The diagnosis of PID was divided into period 1, 2001–2005, and period 2, 2006–2018, because a multicenter study estimated PID epidemiology from 2001 to 2005 in Korea.

A total of 398 PID patients were identified in 101 reports. Of them, 208 (27 reports) and 190 (74 reports) were in periods 1 and 2, respectively (

Fig. 1;

Tables 1,

2). The most frequent PIDs were as follows: V. congenital defects of phagocyte b: functional defects (n=94, 23.6%), III. predominantly antibody deficiencies a: hypogammaglobulinemia (n=82, 20.6%), III. predominantly antibody deficiencies b: other antibody deficiencies (n=62, 15.6%), and IV. disease of immune dysregulation a: hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) & Epstein-Barr virus susceptibility (n=53, 13.3%). Among the diseases, CGD was the most frequently reported PID (n=86, 21.6%) (data not shown). No cases were reported of patients with VI. Defects in intrinsic and innate immunity b: Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease and viral infection, VIIb. auto-inflammatory disorders, and IX. phenocopies of PID.

Among the 10 SCID cases, 5 (50.0%) were reported at Samsung Medical Center (data not shown) [

26,

27]. Among the 53 cases of HLH, 20 (37.7%) were reported from Asan Medical Center. Among the 86 CGD cases, 46 (53.5%) were reported from Seoul National University [

10,

28,

29].

CTLA4 deficiency (n=5, 1.0%) and familial Mediterranean fever (n=4, 1.0%) were not found in period 1 but were reported in period 2.

In VIII. complement deficiencies, 13 cases of C7 and C9 deficiency and atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) and 23 cases of C1, C3, C4, C5, C7, and C9 deficiency and aHUS were defined in periods 1 and 2, respectively.

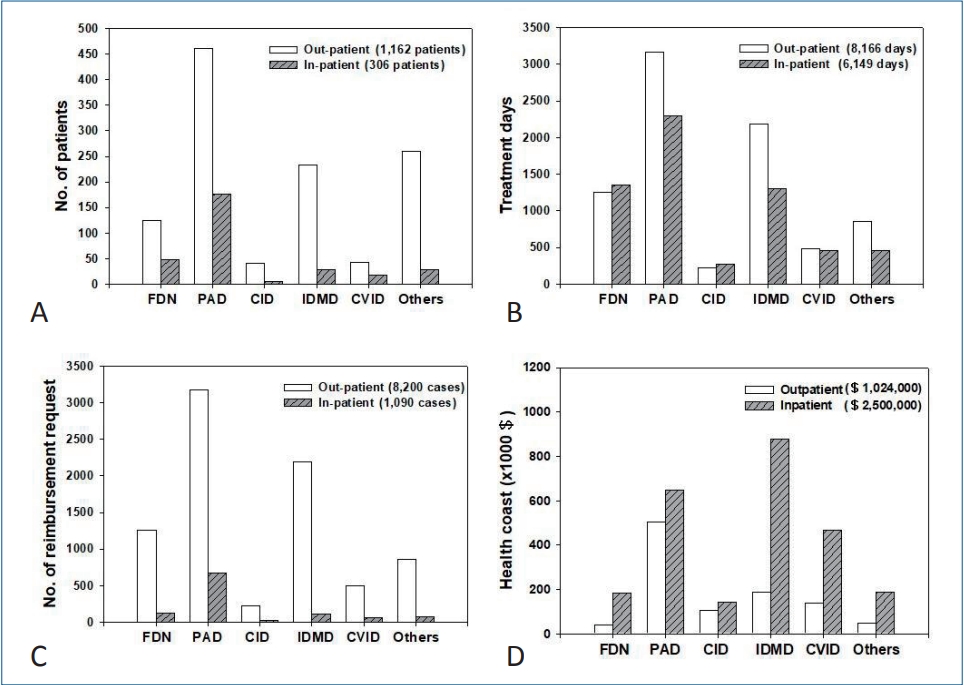

HIRA reimbursement data

The number of PID patients, treatment days, and reimbursement requests as well as the healthcare costs were estimated for 1 year in 2017 using data on the HIRA website (

http://opendata.hira.or.kr/).

A total of 1,162 outpatients and 306 inpatients were treated for 8,166 and 6,149 days, respectively; 124 outpatients (10.7%) and 49 inpatients (16.0%) were treated for functional defect of neutrophils (FDN), 460 (39.6%) and 177 (57.8%) for predominantly antibody deficiency (PAD), 42 (3.6%) and 5 (1.6%) for combined immunodeficiency (CID), 233 (20.1%) and 28 (9.2%) for immunodeficiency associated with other major defects (IDMD), 43 (3.7%) and 18 (5.9%) for common variable immunodeficiency (CVID), and 260 (22.4%) and 29 (9.5%) for other immunodeficiencies (Others), respectively (

Fig. 2A,

Table 1).

Treatment was delivered for 8,166 and 6,149 days for outpatients and inpatients, respectively: 1,249 (15.3%) and 1,357 (22.1%) for patients with FDN, 3,175 (38.8%) and 672 (37.3%) in patients with PAD, 225 (2.7%) and 21 (4.5%) in patients with CID, 2,188 (26.8%) and 118 (21.1%) in patients with IDMD, 496 (6.0%) and 68 (7.5%) in patients with CVID, and 855 (10.4%) and 80 (7.5%) in patients with Others, respectively (

Fig. 2B).

Reimbursement was requested in 8,200 outpatient care episodes and 1,090 inpatient care episodes: 1,261 (15.4%) and 131 (12.0%) for FDN, 3,175 (38.7%) and 672 (61.7%) for PAD, 225 (2.7%) and 21(1.9%) for CID, 2,188 (26.7%) and 118 (10.8%) for IDMD, 496 (6.0%) and 68 (6.2%) for CVID, and 855 (10.4%) and 80 (7.3%) for Others for outpatient and inpatient care episodes, respectively (

Fig. 2C).

Total healthcare cost (reimbursement plus patient copayment) was estimated as $1,024,000 for outpatient care and $2,500,000 for inpatient care in 2017: $188,000 and $877,000 for FDN, $502,000 and $647,000 for PAD, $39,000 and $183,000 for CID, $140,000 and $466,000 for IDMD, $105,000 and $142,000 for CVID, and $50,000 and $186,000 for Others, respectively (

Fig. 2D).

In an outpatient care setting, patients with PAD (n=460) had the highest number of treatment visit days and the highest number of reimbursement requests, and spent the largest amount of healthcare cost (

Fig. 2). In an inpatient care setting, patients with PAD (n=177) had the highest number of inpatient treatment days and highest number of reimbursement requests, while patients with FDN incurred the greatest healthcare costs.

The claims data of the HIRA is an important information source for healthcare service research in Korea [

30]. Despite its importance, there are a few limitations: specifically, these data may involve insufficient cases for rare diseases such as PID and data for a certain age group may be at lower frequency.

In the HIRA database, Korean Standard Classification of Disease Version 7 (KCD-7) codes are used. This is the Korean translation of the International Statistical Classification, 10th Revision (ICD-10) produced by the World Health Organization (WHO) [

31,

32].

In the HIRA database, statistics for the following 6 main KCD-7 codes for PID are as follows: FDN (D71), PAD (D80), CID (D81), IDMD (D82), CVID (D83), and Others (D84). These main codes have several subcategories. For example, according to ICD-10 (WHO version; 2016), PAD (D80) includes D80.0, hereditary hypogammaglobulinemia; D80.1, nonfamilial hypogammaglobulinemia; D80.2, selective deficiency of IgA; D80.3, selective deficiency of IgG; D80.4, selective deficiency of IgM; D80.5, immunodeficiency with increased IgM; D80.6, antibody deficiency with near-normal immunoglobulins or with hyperimmunoglobulinemia; D80.7, transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy; D80.8, other immunodeficiencies with predominantly antibody defects; and D80.9, immunodeficiency with predominantly antibody defects, unspecified.

CID (D81) includes D81.0, SCID with reticular dysgenesis; D81.1, SCID with low T- and B-cell numbers; D81.2, SCID with low or normal B-cell numbers; D81.3, adenosine deaminase deficiency; D81.4, Nezelof syndrome; D81.5, purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency; D81.6, major histocompatibility complex class I deficiency; D81.7, major histocompatibility complex class II deficiency; D81.8, other combined immunodeficiencies; and D81.9, combined immunodeficiency, unspecified. The subcategories above are also found and searchable in HIRA database statistics.

CVID (D83) includes D83.0, CVID with predominant abnormalities of B-cell numbers and function; D83.1, CVID with predominant immunoregulatory T-cell disorders; D83.2, CVID with autoantibodies to B- or T-cells; D83.8, other CVID; and D83.9, common variable immunodeficiency, unspecified.

Since about 40% of PID patients had an antibody deficiency, we took a closer look at the number of patients with PAD (agammaglobulinemia/other antibody deficiency [D80 and D80.0–D80.9 in KCD-7 codes] and CVID [D83 and D83.0–D83.9]), the representative diseases for intravenous Ig replacement therapy (

Fig. 3). The highest number of PAD patients plus CVID patients was observed in the 1st decade (

Fig. 3A). Among them, XLA patients (D80.0 in KCD-7 codes) and CVID patients (D83 and D83.0–D83.9 in KCD-7 codes) are shown in

Fig. 3B. The highest number of these patients were aged 20–29 years (29 and 14 patients, respectively).

Although IUIS classification is updated every 2 years, it has limited ability to reflect the changes in real time for PID coding to enable reimbursement in clinical practice. Several new diagnoses are not properly coded in the reimbursement system in many countries. To address this issue, PID experts should make continuous efforts to both update IUIS classification and apply the IUIS classification to ICD codes in cooperation with government agencies. Education for physicians in the field should also be updated with new PID ICD codes.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation