Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is now widely used for the treatment of children with blood diseases. An important factor in the prognosis of the patient post-transplant is host immune reconstitution (IR) which, if delayed, may increase the risk of infection, disease recurrence and secondary malignancies after transplant

1). IR is affected by various treatment-related variables, such as the period of antibiotic use, routine administration of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVGV), and immunomodulatory treatment after transplant such as donor lymphocyte infusion.

According past literature, IR occurs in the order of monocyte, granulocyte, macrophage, and natural killer (NK) cell, resulting in the restoration of a functional innate immune system. Recovery of the adaptive immune system, however, occurs over a considerably longer period of time, with B cell restoration requiring at least six months, and T cell recovery often taking two years for completion

1).

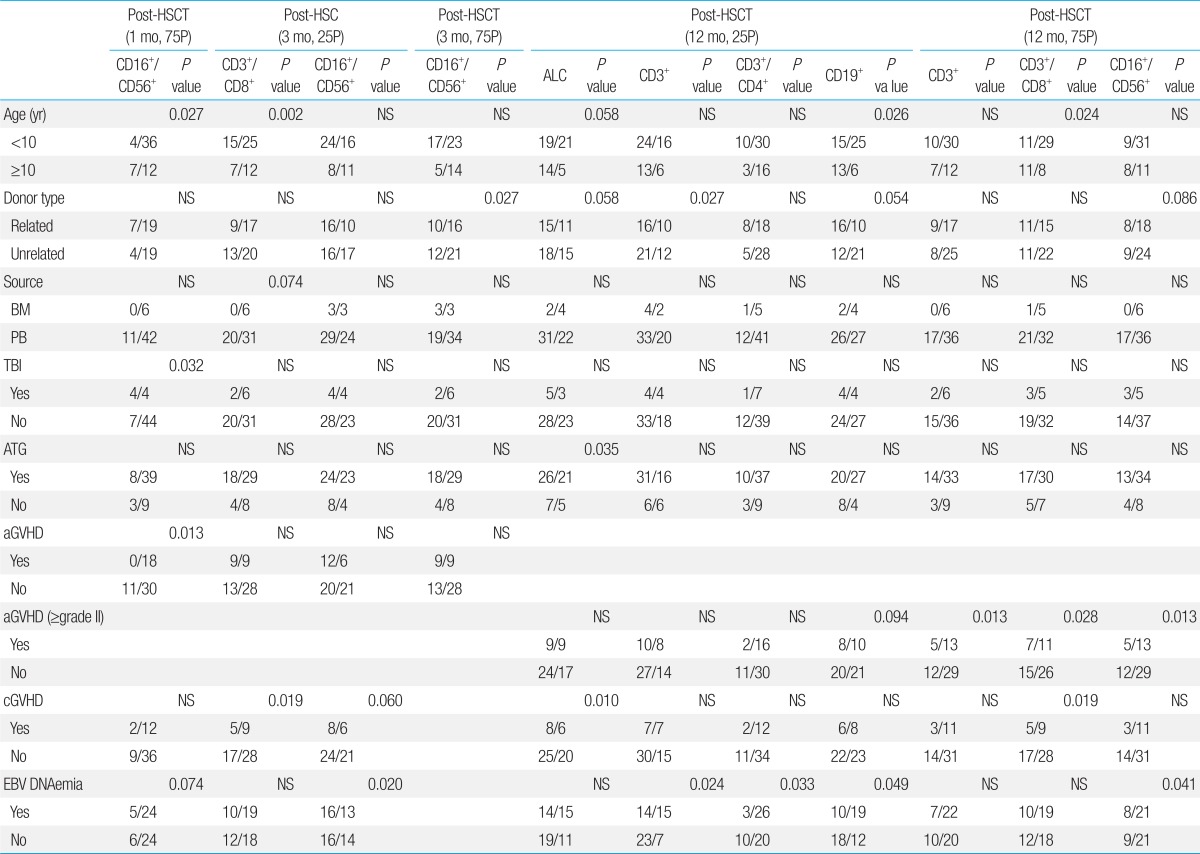

Factors influencing IR at the time of transplant include patient age, donor type, stem cell source, and method of T cell depletion, while prevention and treatment of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) are significant factors influencing IR after transplant

2).

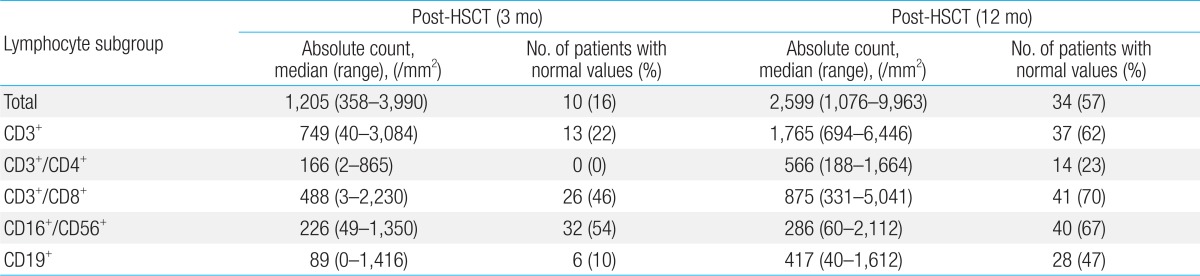

According to a recent Korean study on pediatric recipients of allogeneic HSCT, NK cells and cytotoxic T cells were rapidly restored after HSCT, with 92% and 76% of patients, respectively showing recovery at 3 months post-transplant. However, IR was slower for helper T cells and B cells which showed recovery in 85% and 69% of patients, respectively at 12 months post-transplant

3). Important results that derive from this study are the negative effects of certain conditioning regimens, including the use of total body irradiation (TBI) and antithymocyte globulin (ATG), cord blood as the cell source, and diagnosis of chronic GVHD, on lymphocyte reconstitution.

Despite this and other previous reports on IR

4,

5), studies on IR in pediatric recipients of allogeneic HSCT are few. Also, an important factor which has not yet received full analysis as a possible modulator of IR is post-transplant Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection.

In this study, we evaluated the recovery of each lymphocyte subset in 59 recipients of allogeneic HSCT at our institution. In addition to the impact of well-established variables such as patient age, donor type, acute and chronic GVHD on IR, we also analyzed EBV infection for possible effects on lymphocyte recovery.

Materials and methods

1. Patient cohort

From January 2009 to December 2010, 90 patients received allogeneic HSCT at the Department of Pediatrics, The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary's Hospital. Out of this initial cohort, the following exclusions were made: 14 patients who relapsed within 1 year of transplant, 8 patients who died of transplant-related mortality within 1 year, 2 patients who experienced graft failure, and 7 patients with incomplete records concerning lymphocyte subset recovery. The final study cohort included 59 patients, the major characteristics of whom are summarized in

Table 1.

2. Transplant method

For infection prophylaxis, oral acyclovir was given from the start of conditioning to day 42, and oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was given from the start of conditioning to day -3, and from neutrophil engraftment to at least 6 months after transplant. Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor was given from day 5 to the time when the absolute neutrophil count surpassed 3.0├Ś109/L. For antifungal prophylaxis, we administered intravenous (IV) micafungin (1 mg/kg/day) from the start of conditioning to neutrophil engraftment, followed by oral fluconazole for at least 2 months.

GVHD prophylaxis consisted of IV cyclosporine from day -1 and mini-dose methotrexate (5 mg/m2) given at days 1, 3, 6, and 11.

After transplant, EBV DNA titers were evaluated at fortnightly intervals for up till 3 months post-transplant using a real-time quantitative method. Rituximab was administered only with diagnosis of post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD).

3. Immunophenotypic studies

Bone marrow examination and peripheral blood lymphocyte subset analysis were done at intervals of 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after HSCT.

With peripheral blood, CD3+, CD3+/CD4+, CD3+/CD8+, CD19+ and CD16+/CD56+, the antigens of T cell, B cell, and NK cell, were analyzed through fluorescence-activated cell sorter system, and the absolute values of each subset were calculated using the percentage of each lymphocyte subset and the absolute lymphocyte counts (ALCs).

The normal value of each lymphocyte subset varies according to age

1). In this study, the normal values for each lymphocyte subset, as outlined in a previously published paper, were used

2).

4. Study endpoints

The main study endpoints were as follows; first, we aimed to identify the number of patients with lymphocyte subset recovery, defined as the 25th percentile of normal value. Second, we analyzed for factors that may impact the recovery of each lymphocyte subset, including patient age, donor type, stem cell source, the use of either TBI or ATG in conditioning, diagnosis of acute or chronic GVHD, and EBV DNAemia. For this second analysis, both the 25th and 75th percentile of normal values were used. EBV DNAemia was defined as having a positive value when more than 500 copies were detected per 1 mL by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. All analyses were done for 3 and 12 months post-transplant. In addition, analyses for NK cell recovery and risk factors for NK cell recovery were done at 1 month post-transplant.

5. Statistical analysis

Logistic regression analysis was performed to determine whether the pre- and post-transplant independent variables had a significant impact on recovery of each lymphocyte subset. Factors with a P value<0.05 in univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate study. Statistical analysis was done using the SAS ver. 8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The P value was considered significant when <0.05.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that among lymphocyte subsets, NK cells are the first to recover to normal levels after allogeneic HSCT. The recovery of T cells and B cells is much slower, and amongst T cells, cytotoxic T cells seem to show faster reconstitution than helper T cells

3).

The timing of B cell and T cell recovery has been a matter of controversy, with several previous studies concluding that the B cell recovered faster than the helper T cell, allowing the B cell to stimulate the thymus for T cell maturation and differentiation

1). The results from our study also support the view that B cell recovery precedes helper T cell recovery, allowing for sequential lymphocyte maturation.

Although the NK cell is known to repopulate rapidly, only 47% of the cohort showed normal levels by 1 month since transplant. Factors contributing to delayed early recovery of NK cells were younger patient age, the use of TBI in the conditioning regimen, and previous diagnosis of acute GVHD, with the last factor proving most significant in multivariate study.

Several important points can be made regarding factors that influence the recovery of each lymphocyte subset.

Although patient age has been reported to be an important factor, the age threshold with which the overall cohort has been divided, has varied from 10 to 16 years old

2,

4). Reports on the impact of patient age have also been conflicting. Some researchers have suggested that lymphocyte recovery occurs much faster in older patients

2), while others have shown evidence that recovery is faster in the younger age group

4). In our study, patients in the younger age group showed a significantly lower likelihood of both cytotoxic T cell and B cell recovery at 12 months post-transplant in multivariate analysis. One hypothesis for this result is that younger children may have less mature lymphoid organs that are more prone to damage from the HSCT conditioning regimen.

Previous reports have shown that, although there is no difference in recovery of the innate immune system, related and unrelated transplants have shown discrepancies with regards to recovery of antigen-specific cellular immunity

6). In our study, the effect of donor type in post-transplant IR was not significant in multivariate study, although univariate effects of delayed CD16

+/CD56

+ and CD3

+ cell recovery were noted.

Past studies have shown a faster rate of CD3

+/CD4

+ and CD3

++/CD8

+ lymphocyte recovery in recipients of peripheral blood stem cell transplantation, compared to bone marrow transplantation

7). Our study did not show an advantage for either cell source with regards to IR, consistent with a recent domestic report on immune recovery

3).

The effect of ATG administered as part of the conditioning regimen on IR is a matter of controversy, with at least 1 study concluding that ATG has no significant effect on immunological recovery

8). In our study, the use of ATG had a significantly detrimental effect on the recovery of ALC, as evidenced at 1 year post-transplant.

The possible role of GVHD in IR has been studied considerably, with published data suggesting that acute GVHD and subsequent treatment may delay the recovery of CD3

+/CD4

+ lymphocytes

9). GVHD is known to deter the activities of the thymus, and suppress both CD3

+/CD4

+ and CD3

+/CD8

+ lymphocytes, as well as CD19

+ lymphocytes

5). Our analysis showed that acute GVHD had a significant role in the delayed recovery of innate immunity, as represented by the CD16

+/CD56

+ subset in the early period after transplant. In contrast, diagnosis of chronic GVHD did not have a significant impact in multivariate analysis.

Relatively little is known of the impact of EBV infection on the recovery of specific lymphocyte subsets. Past studies have shown that lymphocyte subset recovery was accelerated with cytomegalovirus infection

5), and that EBV specific T lymphocytes increased with EBV infection

10). The entity of PTLD would indicate that B cell lymphocyte proliferation is increased by EBV infection to the extent of gaining malignant potential

11-

13), and another study found that early infection by EBV or adenovirus delayed immune reconstruction because such early infections are linked to pathogenesis of chronic GVHD

14). In our study, we found that EBV infection, as diagnosed by EBV DNA titers, significantly delayed recovery of CD3

+ cells in multivariate study, was the only important factor in analysis of CD3

+/CD4

+ cell recovery, and was also significant in delayed recovery of CD19

+ cells, although not in multivariate study. Whether EBV infection was actually responsible for delayed CD3

+ recovery is problematic, as past literature supports the converse situation; CD3

+/CD4

+ cells and CD3

+/CD8

+ cells are known to prevent EBV infection

15-

17), and in vivo T cell depletion, as was done for our unrelated donor transplant recipients, may have played a role in subsequent EBV infection. However, considering EBV infection was the independent factor and CD3

+ recovery status the outcome, or dependent factor, in our regression analyses, our data also point to the possibility of delayed CD3

+ recovery by EBV infection.

In conclusion, the lymphocyte subsets in our study recovered in the following order: CD16+/CD56+, CD3+/8+, CD19, and CD3+/4+. In multivariate study, acute GVHD, EBV infection, and younger patient age had major effects on the delayed recovery of CD16+/56+, CD3+, and CD19+ cells, respectively. The results from our pediatric cohort should contribute to a greater understanding of IR after allogeneic HSCT in children, and may provide the basis for larger scale studies of the role of both debated and unrecognized factors such as patient age and EBV infection, in post-transplant immune recovery.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation