Introduction

Reactive arthritis is a sterile arthritis triggered by distant gastrointestinal or urogenital infections, often with some latency. Its genesis suggests that bacterial products contribute to the induction of reactive arthritis1). The pathogenesis of reactive arthritis is incompletely understood, and no optimal treatment is available. Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia , and Campylobacter spp. infections are implicated in the triggering of enteric reactive arthritis. When the arthritis begins, stool cultures are usually negative, and physicians have usually confirmed the background of reactive arthritis via serological methods2). The incidence of Salmonella-induced reactive arthritis varies greatly, from 5 to 14 per 100,000 persons3).

In some patients, symptoms resolve within months, but in others, the symptoms may persist for years. HLA-B27 is the strongest predisposing factor of reactive arthritis. The mechanism by which HLA-B27 mediates inflammation remains unclear4). Reactive arthritis commonly affects persons between 15 to 35 years of age, and it rarely occurs in children5). Only one case of Salmonella-triggered reactive arthritis in a Korean child has been reported6). The objective of this case report is to demonstrate the clinical course and laboratory findings of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27-associated reactive arthritis in a 12-year-old boy after Salmonella enteritis.

Case report

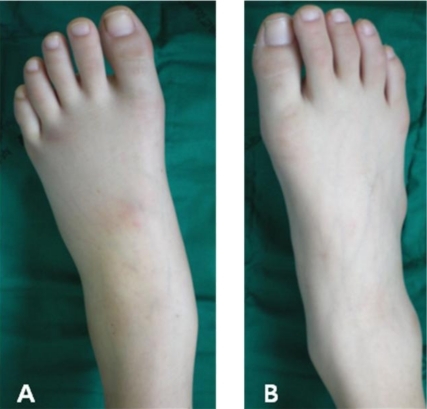

A 12-year-old boy was admitted to Pusan National University Hospital for further examination of multiple sites of arthralgia and arthritis. He had presented at the local clinic after experiencing fever, diarrhea, and abdominal pain for 5 days, for which he had received successful treatment. One week after the onset of the enteritis, he developed arthralgia of the bilateral sacroiliac, wrist, and ankle joints. He had balanitis without urethral discharge, hematuria, or genital ulcers. He had never received a blood transfusion and had no history of sexual contact. On admission, his body temperature was 38℃, pulse was 115 beats/min, and blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg. Physical examination revealed swelling and tenderness of left ankle joint (Fig. 1) and, tenderness on motion and pain over the bilateral wrist and left sacroiliac joints. Other joints were normal. Other systemic examinations were normal. Cardiac auscultation was normal. Laboratory studies showed hemoglobin of 12.8 g/dL, white blood cell count of 21,860/mm3, platelet count of 573,000/mm3, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 74 (0 to 15) mm/hr, and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 3.97 (0 to 0.5) mg/dL. Liver and renal function tests showed no abnormalities. Venereal disease research laboratory and anti-nuclear antibody tests were negative. Urinalysis revealed pyuria, but bacterial culture of urine sample was negative. HLA class I serotyping was positive for B27. We aspirated synovial fluid from the patient's left ankle and left hip joint, which revealed severe inflammation, but Gram staining and culturing of this synovial fluid gave negative results. The stool culture was positive for Salmonella group D. Radiographs of the ankle joint showed only soft tissue swelling, without any visualization of enthesopathic lesions or erosive joint damage. In bone scintigraphy, uptake in the left ankle and sacroiliac joints and right wrist joint was increased (Fig. 2). Considering the clinical features, the preceding symptomatic enteritis, and the positive stool culture for Salmonella group D, we proposed a diagnosis of reactive arthritis. Initially, we treated the patient with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (naproxen, 500 mg every 12 hour) for 7 days, but there was not significant improvement. We added prednisolone (10 mg every 8 hour). He responded well to this treatment.

Discussion

Hans Conrad Reiter reported an early case of urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis associated with spirochete infection3). However, he was responsible for involuntary sterilizations, coerced euthanasia, and medical experiments that outraged many people. Thus, researchers have strongly recommended the name "reactive arthritis" instead of "Reiter's syndrome" due to Reiter's unethical background7).

Reactive arthritis is a sterile synovitis triggered by a distant infection of the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tract. Researchers have proposed its classification into HLA-B27-associated and non-associated forms2) and have observed a number of other clinical features in association with reactive arthritis. According to the American Rheumatism Association criteria, patients with reactive arthritis generally have asymmetric polyarthritis that lasts at least 1 month, as well as 1 or more of the following features: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, balanitis, or radiographic evidence of sacroilitis, periostitis, or heel spurs8).

The present patient developed asymmetric arthritis, balanitis, and pyuria. No features suggestive of cardiovascular, nervous, or pulmonary involvement were present. Generally, the diagnosis of reactive arthritis is clinical; there are no definite diagnostic laboratory tests or radiographic findings. In the present case, apart from the elevated ESR, CRP, and neutrophilic leukocytosis, which suggested a bacterial infection, all laboratory investigation results were negative. Reactive arthritis cases commonly show elevated ESR and acute phase reactants. In addition, reactive arthritis is closely associated with HLA-B27, and our patient was positive for HLA-B27. HLA-B27 antigen, one of the factors contributing to the disease's development, increases the disease risk, and 70 to 80% of patients with reactive arthritis have this antigen2,3). HLA-B27 probably shares some molecular characteristics with bacterial epitopes; researchers have suggested an autoimmune cross-reaction takes part in its pathogenesis3).

The etiology of reactive arthritis is still incompletely understood. However, reportedly the development of reactive arthritis is closely associated with certain bacterial infections, including Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and Chlamydia2,3). We noted that the present patient had Salmonella enteritis prior to reactive arthritis onset.

General treatment of reactive arthritis still most commonly employs NSAIDs and sulfasalazine2,3). Steroids are administered when the patient's inflammatory symptoms are resistant to the NSAIDs. Experience with other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, such azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclosporin, can be useful in treating patients who are unresponsive to the more usual medications. In more aggressive cases, TNF-alpha blockers could be an effective choice. Our patient showed a good response to NSAID and prednisone treatment2,3,9).

The course of reactive arthritis probably varies considerably, depending on the triggering pathogen, the patient's genetic background and gender, and the presence of recurrent arthritis3). Most patients remit completely or have little active disease 6 months after presentation. A European League Against Rheumatism study of 152 patients with reactive arthritis, who were enrolled within 2 months of the onset of arthritis, illustrated this well10). By the end of an additional 24 weeks of observation, almost all patients had very low disease activity, as determined by physician and patient global assessments. After entering peripheral joint arthritis remission, patients occasionally note pain in the joints, at entheses, or in the spine. Chronic persistent arthritis, lasting more than 6 months, occurs in only a small proportion of patients. Children with reactive arthritis, who are positive for HLA-B27, have more severe involvement than children who are negative for HLA-B2811).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation