< Previous Next >

Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 59(6); 2016 |

|

Abstract

Cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) is a vascular malformation characterized by abnormally enlarged capillary cavities without any intervening neural tissue. We report 2 cases of familial CCMs diagnosed with the CCM1 mutation by using a genetic assay. A 5-year-old boy presented with headache, vomiting, and seizure-like movements. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed multiple CCM lesions in the cerebral hemispheres. Subsequent mutation analysis of his father and other family members revealed c.940_943 del (p.Val314 Asn315delinsThrfsX3) mutations of the CCM1 gene. A 10-month-old boy who presented with seizure-like movements was reported to have had no perinatal event. His aunt was diagnosed with cerebral angioma. Brain and spine MRI revealed multiple angiomas in the cerebral hemisphere and thoracic spinal cord. Mutation analysis of his father was normal, although that of the patient and his mother revealed c.535C>T (p.Arg179X) mutations of the CCM1 gene. Based on these studies, we suggest that when a child with a familial history of CCMs exhibits neurological symptoms, the physician should suspect familial CCMs and consider brain imaging or a genetic assay.

Cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) is characterized by abnormally enlarged capillary cavities without intervening brain or spinal cord parenchyma. The prevalence of CCMs has been estimated to exist in 0.4% to 0.8% of the population in several reports1). CCMs can occur in the brain, spinal cord, retina or skin and can show numerous manifestations including headaches, focal neurologic signs, hemorrhagic stroke, seizures or sometimes even death2).

CCMs can present sporadically or be inherited and can be autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance. Familial CCMs are associated with the mutation of 3 genes, i.e., CCM1 (KRIT1), CCM2 (MGC4607), and CCM3 (PDCD10). The CCM1 gene contains 16 coding exons that encode KRIT1, containing three ankyrin domains and one FERM domain. Until now, a strong founder effect has been reported in the Hispanic-American population, and with most families linked to the CCM1 locus3).

Our study reports the first genetically proven, Korean CCM families with CCM1 mutation.

A 5-year-old boy presented with headache, vomiting, and seizure-like motion, although he was without a history of trauma. On physical and neurological examination, he had no focal neurologic deficit.

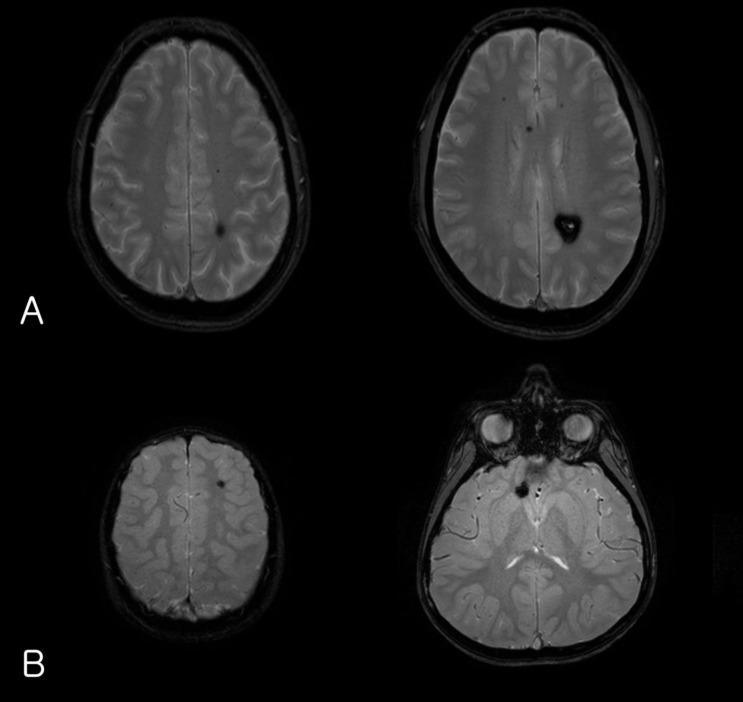

The laboratory findings showed no evidence of electrolyte imbalance or other cause of his seizure. The electroencephalogram (EEG) performed one month after the seizure, revealed diffuse background slowings. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed multiple CCM lesions in his cerebral hemisphere and involving the parietal and temporal lobes as well as basal ganglia (Fig. 1).

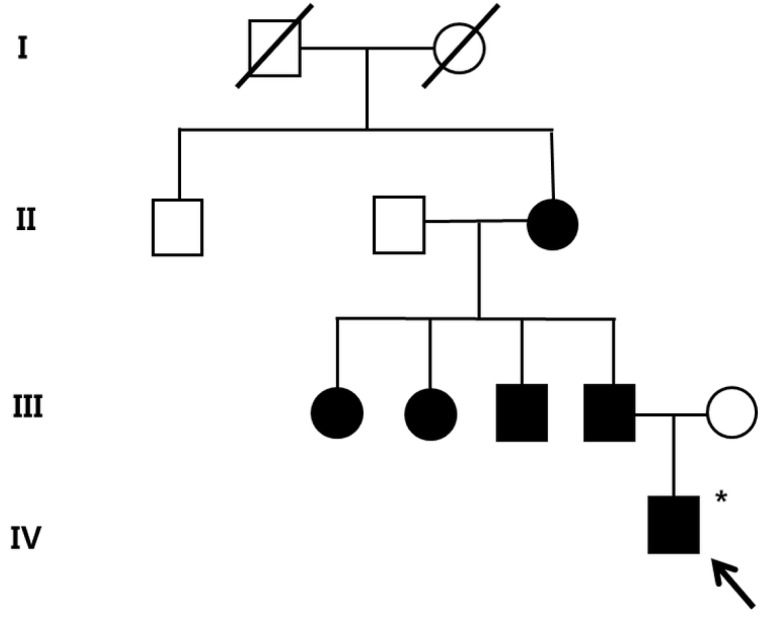

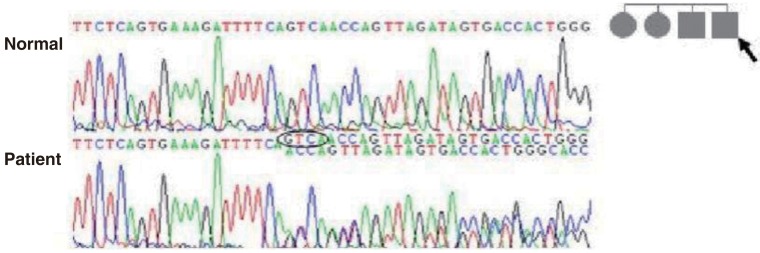

After obtaining his family history of neurologic disease, it was revealed that his grandmother had suffered from dizziness and vomiting, and the subsequent brain MRI revealed CCM and cerebellar infarction. Familial evaluation using genetic and brain MRI screening was performed. With complete radiologic penetrance of the CCMs, his father, one uncle, and 2 aunts were all seen to have CCMs (Fig. 2). Mutation analysis of his family demonstrated c.940_943 del (p.Val314 Asn315delinsThrfsX3) frameshift mutation in exon 7 of the CCM1 gene of the affected family members, and which had not been previously reported (Fig. 3).

Based on the diagnosis of CCM and the associated epilepsy, oxcarbazepine was introduced and the patient had been seizure-free during 3 years of medication. At this time, he has been seizure-free for 2 years after discontinuing the oxcarbazepine.

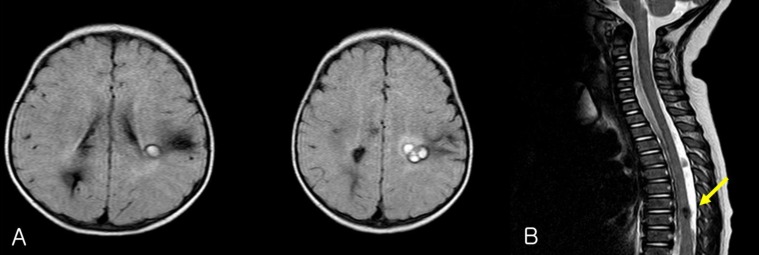

A 10-month-old boy with no perinatal events, presented with seizure-like motion. His aunt was diagnosed with cerebral angioma (Fig. 4). On neurologic examination, the infant had no focal neurologic deficit and no evidence of developmental delay.

EEG recording revealed 2 episodes of electrical seizures with runs of spike discharges from the left temporo-parietal area. An MRI of brain and the entire spine showed multiple angioma in cerebral hemisphere and thoracic spinal cord (Fig. 5).

Familial screening for genetic analysis of CCM1 was done and the patient and his mother demonstrated c.535C>T (p.Arg179X) heterozygous mutation in exon 5 of the CCM1 gene (Fig. 6), and which was already known.

His seizures were well-controlled with the use of vigabatrin and zonisamide medications. At his 4 years of age follow-up, he was neurologically normal and has remained seizure-free without antiepileptic medications.

CCMs may be both sporadic and familial. Some previous reports have described mutation of CCM genes in worldwide familial CCMs4,5,6). In this report, we describe one novel and one known mutation of the CCM1 gene occurring in two, Korean family patients with CCMs with epilepsy.

Kupfs et al.7) first reported families affected by CCMs in 1928. Since then there have been many studies reporting the clinical and neuroradiological features, and after which the recent development of genetic linkage analysis has allowed the full description of CCMs. In recent, large studies, CCM1 mutation showed a clinical penetrance of 62%, and several de novo mutations have also been reported8). In addition, according to Gault et al.9), biallelic CCM1 (KRIT1) mutations, including somatic and germ-line truncating mutation of CCM lesions, may explain the CCM pathophysiology as that occurring in hamartomatous disease.

Recent research data allowed significant progress in determining the function of KRIT1 (CCM1) as a Notch activator which negatively regulates sprouting angiogenesis10). The loss of KRIT1 leads to an induction of angiogenesis caused by impaired DELTA-NOTCH signaling, and disrupts the vascular polarity and lumen formation. Interestingly, exciting recent data suggest that the loss of KRIT1 or PDCD10 induce BMP6-SMAD signaling and endothelial-mesenchymal transition contributing to the development of CCM, and which leads us to search for another therapeutic option such as BMP6 or TGFβ inhibitors11).

In general, the natural course of CCMs is benign, although some patients may suffer from neurological deterioration, primarily related to hemorrhage. According to recently published reports, infratentorial CCM lesions, especially brainstem, are more hemorrhagic events than supratentorial lesions. A larger lesion (>1 cm), early age at presentation (<35 years), and the coexistence of a developmental venous anomaly, are considered as other risk factors for hemorrhage2).

Usually, familial CCMs are more likely to hemorrhage, grow, and present with multiple lesions than those seen in sporadic cases. In addition, a recent study regarding genotype-phenotype correlations shows that CCM3 mutations are more likely to cause cerebral hemorrhage, particularly during childhood, and the increase of the number of gradient-echo-sequence lesions with age differs according to the mutation, with a higher rate in CCM1 than in CCM2 mutations12).

The management of CCMs includes conservative treatment, surgical resection, and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). In general, asymptomatic and small cavernous malformations (CMs) that are silent may be observed conservatively. Follow-up MRI is recommended at 1, 3, and 5 years following the diagnosis for patients younger than 45 years. In contrast, epileptogenic CMs in patients with chronic epilepsy or hemorrhagic CMs are an indication for surgical resection. The goal of surgery is gross total resection because incomplete resection can increase rebleeding with consequent mortality. For difficult cases, such as patients with deep-seated eloquent lesions, SRS may be recommended. However, the long-term results are controversial and radiation-induced morbidities are the principal drawback13).

Several sporadic cases of cavernous malformation involving the central nervous system have been reported in the Korean population, but there are only a few studies with a genetic diagnosis and accompanying familial study. Lee et al.14) reported the occurrence of cerebral and multiple spinal CMs with CCM3 gene mutation, and Lee, et al.15) presented a novel mutation of the CCM1 gene related to CCM and multiple spinal CMs in Korea.

In our patients, thorough history-taking and genetic screening detected familial cases of CCMs. A novel mutation of the CCM1 gene was confirmed in case 1 families over 3 generations and a detailed history provided a clue to identifying a mutation of the CCM1 gene in case 2 and his mother.

In a child with multiple CCMs, family-history taking, brain imaging or genetic assay should be considered in order to evaluate for familial CCMs.

Conflicts of interest

Conflicts of interest:

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Al-Holou WN, O'Lynnger TM, Pandey AS, Gemmete JJ, Thompson BG, Muraszko KM, et al. Natural history and imaging prevalence of cavernous malformations in children and young adults. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2012;9:198–205.

2. Kivelev J, Niemelä M, Hernesniemi J. Characteristics of cavernomas of the brain and spine. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:643–648.

3. Labauge P, Denier C, Bergametti F, Tournier-Lasserve E. Genetics of cavernous angiomas. Lancet Neurol 2007;6:237–244.

4. D'Angelo R, Scimone C, Calabro M, Schettino C, Fratta M, Sidoti A. Identification of a novel CCM2 gene mutation in an Italian family with multiple cerebral cavernous malformations and epilepsy: a causative mutation? Gene 2013;519:202–207.

5. Reddy S, Gorin MB, McCannel TA, Tsui I, Straatsma BR. Novel KRIT1/CCM1 mutation in a patient with retinal cavernous hemangioma and cerebral cavernous malformation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010;248:1359–1361.

6. Wang X, Liu XW, Lee N, Liu QJ, Li WN, Han T, et al. Features of a Chinese family with cerebral cavernous malformation induced by a novel CCM1 gene mutation. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:3427–3432.

7. Kupfs H. Uber heredofamiliare Angiomatose des Gehirens und der Retina, ihre Beziehungen zueinander und zur Angiomatose der Haut. Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr 1928;113:651–686.

8. Denier C, Labauge P, Brunereau L, Cave-Riant F, Marchelli F, Arnoult M, et al. Clinical features of cerebral cavernous malformations patients with KRIT1 mutations. Ann Neurol 2004;55:213–220.

9. Gault J, Shenkar R, Recksiek P, Awad IA. Biallelic somatic and germ line CCM1 truncating mutations in a cerebral cavernous malformation lesion. Stroke 2005;36:872–874.

10. Wustehube J, Bartol A, Liebler SS, Brütsch R, Zhu Y, Felbor U, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformation protein CCM1 inhibits sprouting angiogenesis by activating DELTA-NOTCH signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:12640–12645.

11. Maddaluno L, Rudini N, Cuttano R, Bravi L, Giampietro C, Corada M, et al. EndMT contributes to the onset and progression of cerebral cavernous malformations. Nature 2013;498:492–496.

12. Denier C, Labauge P, Bergametti F, Marchelli F, Riant F, Arnoult M, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in cerebral cavernous malformations patients. Ann Neurol 2006;60:550–556.

13. Kivelev J, Niemela M, Hernesniemi J. Treatment strategies in cavernomas of the brain and spine. J Clin Neurosci 2012;19:491–497.

Fig. 1

(A) Gradient-echo axial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the patient's father's brain showing a cavernous malformation in the parietal deep-white matter as well as multiple microbleeds in the brain. (B) Brain MRI of the index patient showing multiple cavernous angiomas.

Fig. 2

The pedigree of the family of patient-1 with cerebral cavernous malformations. Filled circles and squares indicate affected members; the index patient (arrow) and the father, uncle, aunts, and grandmother. A filled square or circle with a diagonal indicates deceased individuals; *Affected individual who did not go through the genetic test.

Fig. 3

Mutation analysis of the father of patient-1 (arrow) revealed c.940_943 del (p.Val314 Asn315delinsThrfsX3) mutations of the CCM1 gene. This is a novel mutation of the CCM1 gene in patients with cerebral cavernous malformation.

Fig. 4

Pedigree of the family of patient-2 with cerebral cavernous malformations. Filled circles and squares indicate affected members; the index patient (arrow) and mother. *Affected individual who did not go through the genetic test.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation