Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 59(Suppl 1); 2016 |

|

Abstract

Blau syndrome (BS) is a rare autosomal dominant, inflammatory syndrome that is characterized by the clinical triad of granulomatous dermatitis, symmetric arthritis, and recurrent uveitis. Mutations in the nucleotide oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) gene are responsible for causing BS. To date, up to 30 Blau-associated genetic mutations have been identified within this gene. We report a novel NOD2 genetic mutation that causes BS. A girl, aged 8 years, and her brother, aged 10 years, developed erythematous skin rashes and uveitis. The computed tomography angiogram of the younger sister showed features of midaortic dysplastic syndrome. The brother had more prominent joint involvement than the sister. Their father (38 years) was also affected by uveitis; however, only minimal skin involvement was observed in his case. The paternal aunt (39 years) and her daughter (13 years) were previously diagnosed with sarcoidosis. Mutational analysis revealed a novel c.1439 A>G mutation in the NOD2 gene in both siblings. The novel c.1439 A>G mutation in the NOD2 gene was found in a familial case of BS. Although BS is rare, it should always be considered in patients presenting with sarcoidosis-like features at a young age. Early diagnosis of BS and prompt multisystem workup including the eyes and joints can improve the patient's outcome.

Blau syndrome (BS, MIM No. 186580) is a rare monogenic auto-inflammatory granulomatous disorder first described in 1985 by the pediatrician Edward Blau. It is an autosomal dominant chronic inflammatory syndrome with classical clinical triad of granulomatous dermatitis, symmetric arthritis and recurrent uveitis in young children1). Histology of affected tissues demonstrates epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells organized in typical granulomas.

BS and sarcoidosis show many similar features, such as noncaseating granuloma, skin rash and eye involvement. Early-onset sarcoidosis (EOS, MIM No. 609464) was previously considered to be a distinctive type of childhood sarcoidosis with a younger age of onset and a progressive course. BS and EOS are now considered to be the same disease, as both were later found to have mutations in NOD2 gene2,3).

The number of different NOD2 mutations associated with Blau has expanded greatly over the past decades. Currently, up to 30 different mutations in NOD2 have been reported in association with BS or other related diseases in the Human Genomic Mutation database4,5). There has been only one previous report of BS in Korean family, which showed a R334 W substitution, a common mutation in BS6).

Here, we describe a novel mutation in NOD2 gene shared by two siblings, and their clinical phenotypes.

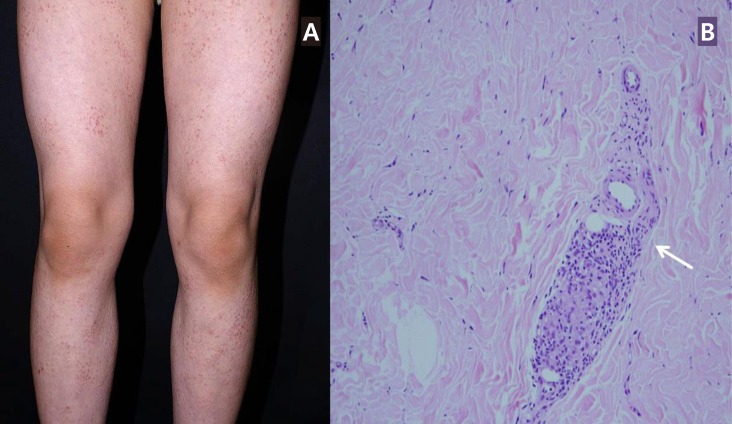

A 8-year-old girl presented with conjunctival injection which was later diagnosed as anterior uveitis that was treated with topical corticosteroid. She reported having generalized multiple small papules (Fig. 1A) since the age of 6 months. Her paternal aunt was recently diagnosed with sarcoidosis, and she was referred under the suspicion of sarcoidosis.

On presentation, her blood pressure as measured in the upper extremities was 126/60 mmHg. The blood pressure in her lower extremities was lower, checking at 95/50 mmHg. Systolic bruit was audible over her left upper chest. Echocardiogram and computed tomography (CT) angiogram revealed stenosis of the thoracoabdominal aorta with diffuse luminal narrowing from the aortic isthmus to the suprarenal arteries (Fig. 2), suggestive of midaortic dysplastic syndrome. Laboratory tests including complete blood cell count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and thyroid function tests were all normal. A skin biopsy of her lower limbs showed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 1B). Case 1 was not treated with systemic immunosuppressive medications due to mild symptoms.

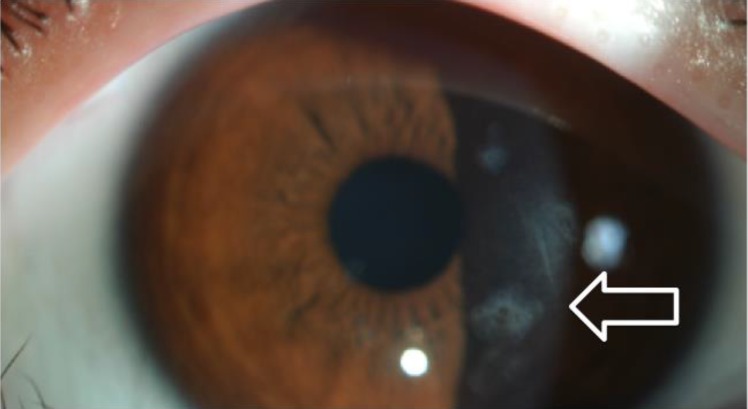

A 10-year-old brother of case 1 was referred for sarcoidosis work up. He had small erythematous papules of 1–2 mm in size in both arms (Fig. 3A). The skin lesion started to develop at the age of 6 months. He had subcutaneous nodules in the wrists and ankles. He complained of pain in multiple lower limb joints, especially while sitting down or squatting, indicating arthritic changes. He suffered from uveitis since very young age, which was treated by topical corticosteroids. His eye exam revealed multiple mild subepithelial opacities on both eyes (Fig. 4) along with focal posterior synechia. His blood pressure was normal and 1/6 systolic murmur was audible on auscultation, but echocardiogram was normal. CBC, ESR, CRP, and thyroid function tests were all normal. CT of chest and abdomen were normal. A skin biopsy of his lower limbs showed noncaseating granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 3B). Case 2 was also was not treated with systemic immunosuppressive medications due to mild symptoms.

Their father (38 years) was also affected by uveitis but with minimal skin rashes. The paternal aunt (39 years) and her daughter (13 years) were diagnosed as sarcoidosis. They suffered from systemic erythematous skin rashes as well (Fig. 5).

Due to the siblings' early onset of symptoms and extensive family history of sarcoidosis like features, presence of BS was suspected.

Under the suspicion of familial granulomatous disease, genetic analysis for BS was performed. The Institutional Review Boards of Seoul National University Hospital approved this study and written consent was obtained from the participants. Sequencing of the NOD2 gene revealed a novel heterozygous mutation, c.1439 A>G (p.His480Arg) in exon 4, in both patients. Unfortunately, DNA samples of other family members were unavailable. This single nucleotide variant (SNV) was not found in the in-house database containing the exomes of 250 Korean individuals7).

BS is a granulomatous autoinflammatory disease caused by mutation in the region encoding for the NOD2 gene with subsequent dysregulation of the inflammatory response and formation of non-caseating granulomas. Skin rash is the first symptom to appear in most cases, usually in the first year of life. In our case report, both siblings exhibited skin rash from 6months of age, which is consistent with BS. Polyarthritis is frequently observed between ages of 2–4 years, and uveitis develops in 60%–80% of the patients around the age of 48 months8). However in contrast to skin rashes, arthritis and uveitis sometimes can go undetected if symptoms are mild. Which is also true in our report, as case 1 presented with uveitis at the age of 8, and case 2 did not have evaluation regarding his joint discomfort until the age of 10 years.

NOD2 protein is a member of the NOD-like receptor family, primarily expressed in antigen-presenting cells, such as monocytes and macrophages. NOD2 has a tripartite structure with 2 N-terminal caspase recruitment domains, 1 centrally located NTPase triphosphatase domain (NACHT domain) and a C-terminal domain comprising multiple leucine rich repeat motifs, which bind muramyl dipeptide (MDP), a degradation product of the bacterial peptidoglycan. The MDP activates NOD2, which in turn activates nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), leading to inflammation and apoptosis2).

Here we report for the first time in Korea, a familial case of novel mutation of NOD2 causing BS. Genetic analysis of NOD2 from the 2 siblings revealed a novel SNV of an H480R mutation in the NACHT region. To date, 30 different mutations in NOD2 have been identified in patients with BS (n=14), early-onset sarcoidosis (n=7), pediatric granulomatous arthritis (n=5), granulomatous synovitis with uveitis (n=3) or Blau arteritis (n=1), mostly in the NACHT region4,5,9). Two of the mutations (R334Q and R334W) in the nucleotide-binding domain of the NOD2 gene are responsible for more than 50% of BS cases3,9), including a Korean case6). Because the activation of NOD2 involves oligomerization initiated by the NACHT-domain, mutations in this domain may decrease the threshold for spontaneous oligomerization of NOD210), and this gain-of-function mutation leads to the hyper-activation of NF-κB2).

Atypical cases of BS may display various additional features such as interstitial nephritis and cerebral infarction11,12). Case 1 in our report exhibited vascular involvements, which is not a very common feature of BS. Previous reported cardiovascular manifestations of BS include Valsalva aneurysm as a form of auto-immune aortitis13), myocardial hypertrophy with the C495Y mutation14) and recurrent episodes of congestive heart failure with G481D mutation15). Both the C495Y mutation and the G481D mutation, causing cardiovascular changes showed a high level of MDP-independent NF-κB activation. It would be of interest to see if the novel mutation in H480R also leads to NF-κB activation.

Interestingly, case 1 showed vascular involvement, whereas case 2 prominently displayed joint involvement with early onset of uveitis. Family members sharing the same mutation often showed diverse clinical presentations in previous reported cases as well14). This may indicate that a specific monogenic genetic mutation is not enough to completely control phenotype, and other factors such as epigenetics are at work.

The family pedigree in our case strongly indicates that the BS mutation is inherited through the paternal side of the family. The father, paternal aunt and her daughter showing sarcoidosis like features are very likely to have mutation consistent with BS, although we were not able to confirm this with genetic analysis. As BS is inherited in autosomal dominant fashion, one can expect that one of the paternal grandparents to have been effected by BS but neither of the paternal grandparents showed significant symptoms. BS with very mild symptoms can go unnoticed, or one of the grandparents could have had germline mosaicism. The variability in clinical features in different family members adds difficulty in making early diagnosis of BS, as illustrated in our case. Although our sibling cases first demonstrated skin lesions at the age of 6 months, their diagnosis was delayed until the age of 8 and 10, respectively. Fortunately the siblings did not show significant visual disturbances or limitation of joint movements, but early detection of uveitis and arthritis is vital to prevent possible irreversible complications.

In conclusion, our report identifies a novel mutation in NOD2 gene that lead to a familiar case of BS. We emphasize that BS should always be considered in young patients presenting with systemic skin lesions and granulomatous inflammation, suggestive of early onset sarcoidosis or juvenile inflammatory arthritis. Early diagnosis through skin biopsy and genetic analysis can improve the quality of life and life expectancy of the patients. The clinical phenotype is highly variable even if same mutation is shared, and thorough multisystem work-up is warranted.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by a grant (HI12C0014) from the Korean Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea.

Notes

Conflict of interest:

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

2. Kanazawa N, Okafuji I, Kambe N, Nishikomori R, Nakata-Hizume M, Nagai S, et al. Early-onset sarcoidosis and CARD15 mutations with constitutive nuclear factor-kappaB activation: common genetic etiology with Blau syndrome. Blood 2005;105:1195–1197.

3. Miceli-Richard C, Lesage S, Rybojad M, Prieur AM, Manouvrier-Hanu S, Hafner R, et al. CARD15 mutations in Blau syndrome. Nat Genet 2001;29:19–20.

4. Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Shaw K, Phillips A, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: building a comprehensive mutation repository for clinical and molecular genetics, diagnostic testing and personalized genomic medicine. Hum Genet 2014;133:1–9.

5. BIOBASE Biological Databases. Human gene mutation database (HGMD professional) [Internet]. Waltham (MA): BIOBASE Biological Databases, c2016;cited 2015 Sep 25. Available from: http://www.biobase-international.com/hgmd.

6. Son S, Lee J, Woo CW, Kim I, Kye Y, Lee K, et al. Altered cytokine profiles of mononuclear cells after stimulation in a patient with Blau syndrome. Rheumatol Int 2010;30:1121–1124.

7. Lee Y, Lee JJ, Kim S, Lee SC, Han J, Heu W, et al. Dissecting the critical factors for thermodynamic stability of modular proteins using molecular modeling approach. PLoS One 2014;9:e98243

8. Rose CD, Wouters CH, Meiorin S, Doyle TM, Davey MP, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Pediatric granulomatous arthritis: an international registry. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3337–3344.

9. Caso F, Costa L, Rigante D, Vitale A, Cimaz R, Lucherini OM, et al. Caveats and truths in genetic, clinical, autoimmune and autoinflammatory issues in Blau syndrome and early onset sarcoidosis. Autoimmun Rev 2014;13:1220–1229.

10. Chamaillard M, Philpott D, Girardin SE, Zouali H, Lesage S, Chareyre F, et al. Gene-environment interaction modulated by allelic heterogeneity in inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:3455–3460.

11. Ting SS, Ziegler J, Fischer E. Familial granulomatous arthritis (Blau syndrome) with granulomatous renal lesions. J Pediatr 1998;133:450–452.

12. Emaminia A, Nabavi M, Mousavi Nasab M, Kashef S. Central nervous system involvement in Blau syndrome: a new feature of the syndrome? J Rheumatol 2007;34:2504–2505.

14. Arostegui JI, Arnal C, Merino R, Modesto C, Antonia Carballo M, Moreno P, et al. NOD2 gene-associated pediatric granulomatous arthritis: clinical diversity, novel and recurrent mutations, and evidence of clinical improvement with interleukin-1 blockade in a Spanish cohort. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3805–3813.

Fig. 1

(A) Erythematous papular skin lesions observed in the lower extremities of case 1. (B) Histopathology of skin biopsy (H&E, ×200) from case 1 showing noncaseating granulomatous inflammation (arrow).

Fig. 2

3-Dimensional cardiac computed tomography image of case 1. Image shows stenosis at aortic isthmus (arrow).

Fig. 3

(A) Erythematous papular skin lesions observed in the lower extremities of case 2. (B) Histopathology of skin biopsy (H&E, ×200) from case 2 showing noncaseating granulomatous inflammation (arrow).

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation