Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 59(Suppl 1); 2016 |

|

Abstract

Esophageal granular cell tumor (GCT) is a rare neoplasm originating from the Schwann cells of the submucosal neuronal plexus. Histology is the gold standard for its diagnosis. Endoscopic resection or surgical excision should be considered, depending on the potential for malignancy. Here, we report a case of an esophageal GCT in an adolescent. A 12-year-old boy presented with a 1-year history of dysphagia and vomiting. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination and esophagography showed narrowing of the midesophagus, and computed tomography angiography of the thoracic aorta revealed an esophageal or periesophageal mass posterior to the paratracheal segment of the esophagus. The tumor was surgically excised, and based on the pathological findings, esophageal GCT was diagnosed.

The granular cell tumor (GCT) was first described by Abrikossoff in 1926. This first report was of a GCT of the tongue. He also reported the first case of GCT of the esophagus in 19311). GCT is a submucosal or subcutaneous tumor that is most commonly found in the skin, tongue, and breast. Tumors involving the gastrointestinal (GI) tract account for 8% of all GCT cases, while only 2% of these occur in the esophagus. Esophageal GCT is more common in women and those of African descent, and most cases occur in the fourth, fifth, and sixth decades of life. A few cases of GCT of the esophagus have recently been reported in pediatric patients2,3). Here we report a case of esophageal GCT in a pediatric patient who was admitted for the evaluation of persistent vomiting.

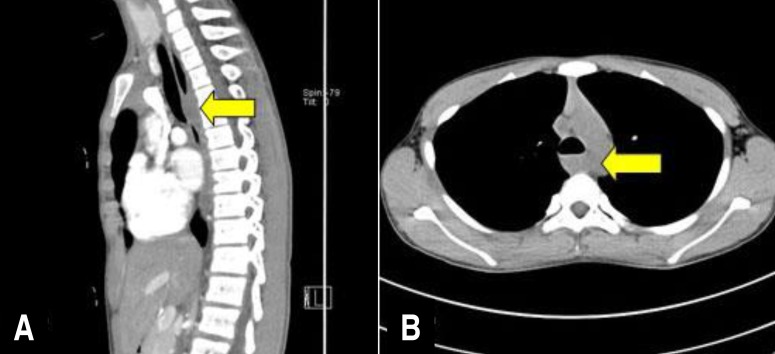

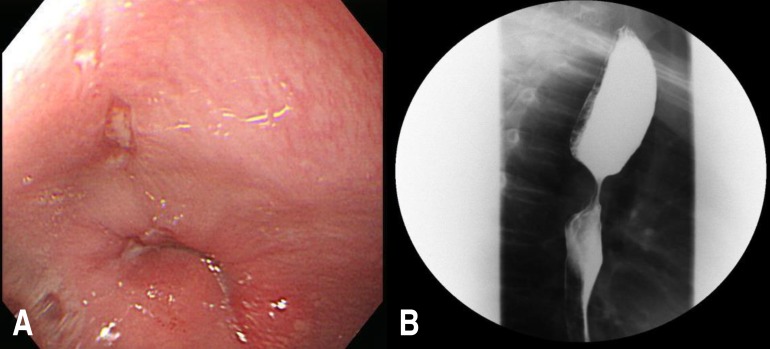

A 12-year-old boy presented with a 1-year history of progressively worsening intermittent dysphagia and vomiting. One year previously, he visited a local clinic for the evaluation of vomiting and dysphagia. He was diagnosed with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) by barium esophagography and was prescribed GERD medication. However, his symptoms worsened a few months previously, so he visited our hospital for evaluation. No abnormalities were observed on physical examination and routine blood tests. An upper GI endoscopic examination revealed narrowing of the middle portion of the esophagus with a small area of erosion (Fig. 1A). When the air supply by scope, narrowing of the esophagus was sustained, and the endoscope could not pass. Esophagography showed esophageal narrowing at the carina (1.6 cm in length) with a mild passage disturbance (Fig. 1B). Computed tomography angiography of the thoracic aorta was performed to evaluate the vascular ring and check for structural abnormalities. On computed tomography angiography of the thoracic aorta, an esophageal or periesophageal mass about 25 mm in size posterior to the paratracheal segment of the esophagus (Fig. 2) was detected.

We performed esophageal tumor extirpation. The tumor, which measured approximately 3 cm×4 cm, had invaded the submucosa in the midthoracic esophagus. Its gross appearance was irregular and hard. A histological examination revealed epithelioid cells with abundant clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm and small nuclei. The tumor cells showed diffuse periodic acid-Schiff positivity and S100 immunoreactivity (Fig. 3). These findings confirmed the diagnosis of GCT. Postoperative esophagography revealed no anastomotic leak or passage disturbances. Two months later, the patient's dysphagia had resolved and endoscopy showed no evidence of a residual tumor or stricture (Fig. 4).

Neoplasms are a relatively rare cause of vomiting and dysphagia in children, and esophageal cancers such as squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma are also rare in children4). Furthermore, GCT is relatively uncommon in adults and very rare in childhood2,3). There are 2 reported cases of esophageal GCT in children (Table 1)2,3). In adults, GCT is found in many parts of body, especially in the oral mucosa, tongue, subcutaneous tissue, skin, breast, thyroid gland, respiratory system, nervous system, and all segments of the GI tract1). It is found most commonly in the skin and rare in other sites in children. Multiple tumors or tumors in more than one family member have been reported in children2).

The esophagus is the most common site of GCT within the digestive tract. GCTs and about one third of all cases of GI-tract GCT occur in the esophagus5). Esophageal GCT is found in the distal (50%–65%), proximal (15%–40%), and midesophagus (20 %). Most cases are solitary, but multiple lesions in the esophagus occur in 10% of cases2,6). Cases of esophageal GCT are usually asymptomatic and found incidentally during endoscopy or a GI contrast study. When the tumor is >2 cm, the most common chief complaint is dysphagia, while dyspepsia, chest pain, cough, nausea, and hoarseness occur less frequently7,8).

The endoscopic appearance of GCT is a yellowish-white, smooth surfaced, sessile, and firm submucosal lesion covered with intact overlying mucosa. In the diagnosis and treatment of esophageal GCT, the use of endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is important since it helps determine the appropriate treatment from among endoscopic resection and surgical excision by assessing tumor size, location, and invading layer. EUS and endoscopy findings are useful for the differential diagnosis of GCT, esophageal cyst, inflammatory polyp, and lipoma. However, these studies cannot differentiate among neoplasm types such as leiomyoma and GCT. Therefore, histology and immunohistochemical (IHC) (immunoperoxidase) staining are essential in making the correct diagnosis8,9).

GCT was originally considered to be of myogenic origin. However, a recent electron microscopic (EM) and IHC study suggested that GCT has a Schwann cell origin. This tumor has polygonal and fusiform cells with small dark nuclei and fine, abundant, and granular cytoplasm. The cytoplasm is eosinophilic, periodic acid-Schiff positive, and diastase resistant10). IHC staining for S100 protein demonstrates that the tumor has a Schwann cell origin, while the EM examination shows a prominent basement membrane and a cytoplasm packed with lysosomes2).

Even if the natural history of the tumor is unknown, most cases of esophageal GCT are benign. However, 1.5%–2.7% of reported cases are considered malignant. Malignant esophageal GCT are usually larger (>40 mm), grow rapidly, tend to frequently recur after resection, and have subtle histological features. Fanburg-Smith used 6 histologic criteria to classify GCTs, including nuclear pleomorphism, high nuclear/cytoplasm ratio, increased mitotic rate (>2/10 high power fields), vesicular nuclei, large nucleoli, and tumor cell necrosis and spindling10,11,12). Neoplasms were classified as histologically malignant, atypical, or benign according to number of fulfilled criteria. However, multifocality does not indicate an increased risk of malignant behavior.

Most cases of GCT were benign on long-term follow-up, and no recurrence was seen in patients treated with surgery or endoscopic excision. The follow-up period ranged from 6 months to 5 years1) and the standard treatment remains controversial. The treatment is conservative management with regular endoscopic follow-up for tumors <10 mm in diameter without malignant features. Surgical or endoscopic excision is warranted for tumors >20 mm in diameter, patients who complain of symptoms, or cases of suspected malignancy10). However, other studies recommend endoscopic excision for small and asymptomatic lesions because benign and malignant lesions may be indistinguishable based on clinical symptoms2,11).

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was an effective treatment in a recently reported case, and EUS is the most useful method for determining whether the tumor is a candidate for endoscopic removal, with parameters including small size (<20 mm) and no muscle layer invasion10). EMR is less invasive and has fewer complications than esophagectomy10). In the current reports, endoscopic resection or surgical excision is recommended for patients with esophageal GCT due to the potential of malignancy6,11). In GCTs that are 10–20 mm in diameter, endoscopic resection (EMR or endoscopy submucosal dissection [ESD]) may be preferable. For large esophageal GCTs (>20 mm), esophagectomy was performed until quite recently10) and submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection (STER) is considered for lesions 20–30 mm in diameter within the submucosa8). However, since the use of EMR, STER, and ESD for esophageal tumor resection in children has not been reported, the treatment choice must be made carefully in this population.

In conclusion, esophageal GCT is a rare and mostly benign neoplasm in children. Here, we report a case of esophageal GCT in a pediatric patient with persistent vomiting and dysphagia for 1 year. In GCT, endoscopic and EUS evaluation defines the tumor location and extent. EMR, STER, and ESD are safe and useful procedures, whereas surgical excision may be necessary if malignancy is suspected, symptomatic relief is required, or the tumor is larger (>20 mm). We report the successful surgical removal of an esophageal GCT in a pediatric patient. Although neoplasms are rare causes of persistent vomiting and dysphagia in children, they should be considered in the assessment of young patients with these symptoms.

Notes

Conflict of interest:

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

1. Percinel S, Savas B, Yilmaz G, Erinanc H, Kupana Ayva S, Bektas M, et al. Granular cell tumor of the esophagus: three case reports and review of the literature. Turk J Gastroenterol 2008;19:184–188.

2. Buratti S, Savides TJ, Newbury RO, Dohil R. Granular cell tumor of the esophagus: report of a pediatric case and literature review. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;38:97–101.

3. Mohammad S, Naiditch JA, Jaffar R, Rothstein D, Bass LM. Granular cell tumor of the esophagus in an adolescent girl. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2012;54:715

4. Issaivanan M, Redner A, Weinstein T, Soffer S, Glassman L, Edelman M, et al. Esophageal carcinoma in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:63–67.

5. Ha J, Lee OJ, Cho HS, Jung TS, Yoon JH, Lee EJ, et al. Endoscopically removed granular cell tumor of the esophagus: a case report and review of Korean literature. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc 2003;26:84–89.

6. Xu GQ, Chen HT, Xu CF, Teng XD. Esophageal granular cell tumors: report of 9 cases and a literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:7118–7121.

7. Simsek H, Ozaslan E, Sokmensuer C, Tatar G. Multifocal granular cell tumor of the esophagus: a case report. Turk J Cancer 2002;32:116–122.

8. Chen WS, Zheng XL, Jin L, Pan XJ, Ye MF. Novel diagnosis and treatment of esophageal granular cell tumor: report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;97:296–302.

9. Squillace SJ, Deutsch JC. Granular cell tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. Visible Human J Endosc 2010;9(2.

10. Nakajima M, Kato H, Muroi H, Sugawara A, Tsumuraya M, Otsuka K, et al. Esophageal granular cell tumor successfully resected by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Esophagus 2011;8:203–207.

Fig. 2

(A, B) Computed tomography showing a esophageal or periesophageal mass (~25 mm) posterior to the paratracheal segment (arrows).

Fig. 3

Histological appearance of the granular cell tumor. (A) Epithelioid cells with abundant clear to eosinophilic cytoplasm and small nuclei (H&E, ×200). (B) The tumor cells show diffuse immunoreactivity for S100 (S100, ×200).

Fig. 4

Postoperative esophagography (A) and upper endoscopy (B) showing no evidence of residual tumor or stricture.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation