Article Contents

| Korean J Pediatr > Volume 57(3); 2014 |

|

Abstract

Purpose

Administration of antiretroviral drugs to mothers and infants significantly decreases mother-to-child human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission; cesarean sections and discouraging breastfeeding further decreases this risk. The present study confirmed the HIV status of babies born to mothers infected with HIV and describes the characteristics of babies and mothers who received preventive treatment.

Methods

This study retrospectively analyzed medical records of nine infants and their mothers positive for HIV who gave birth at Korea University Ansan Hospital, between June 1, 2003, and May 31, 2013. Maternal parameters, including HIV diagnosis date, CD4+ count, and HIV ribonucleic acid (RNA) copy number, were analyzed. Infant growth and development, HIV RNA copy number, and HIV antigen/antibody test results were analyzed.

Results

Eight HIV-positive mothers delivered nine babies; all the infants received antiretroviral therapy. Three (37.5%) and five mothers (62.5%) were administered single- and multidrug therapy, respectively. Intravenous zidovudine was administered to four infants (50%) at birth. Breastfeeding was discouraged for all the infants. All the infants were negative for HIV, although two were lost to follow-up. Third trimester maternal viral copy numbers were less than 1,000 copies/mL with a median CD4+ count of 325/µL (92-729/µL). Among the nine infants, two were preterm (22.2%) and three had low birth weights (33.3%).

Conclusion

This study concludes that prophylactic antiretroviral therapy, scheduled cesarean section, and prohibition of breastfeeding considerably decrease mother-to-child HIV transmission. Because the number of infants infected via mother-to-child transmission may be increasing, studies in additional regions using more variables are necessary.

It is estimated that more than 1,800 babies worldwide contract human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from their mothers every day. Many of these cases occur in Africa1,2). The probability of infection from mothers who do not receive treatment is higher in Africa (25%-52%) than the United States (US) or Europe (12%-30%)3). HIV progresses more rapidly in babies, with approximately one-quarter of newborns dying within 1 year and two-thirds within 2 years after birth. In addition, since babies present with many initial symptoms as well as nonspecific symptoms, HIV infection is quite different in babies compared to adults4). Accordingly, since there are many cases in which there is no prevention for mother-to-child transmission, HIV in newborn babies is diagnosed late; the rapid progress of the disease can lead to death. Therefore, prompt diagnosis and preventive measures are critical. The pediatric acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) clinical trial group 076 was established in the US in 1994 and uses a 3-step preventive chemotherapy: zidovudine administration to mothers starting from the 14th week of pregnancy, zidovudine intravenous injection during delivery, and administration of zidovudine syrup to the newborn for 6 weeks after birth. The level of mother-to-child HIV transmission in the administration group was 8.3% vs. 25.5% in the control group (a 68% difference)5). In addition, by reducing the time the baby is exposed to mother's body fluids owing to Caesarian section and by prohibiting breastfeeding, which is another a route of mother-to-child HIV transmission, the infection rate decreased to less than 1%6). However, although the 3-step prevention significantly lowers the probability of mother-to-child HIV transmission, pregnancies of mothers with HIV are still considered high risk; this is not only because of HIV itself, but also because the risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and infant mortality due to the administration of antiretroviral drugs have not yet been eliminated7).

This study aimed to investigate the mother-to-child HIV transmission with zidovudine prevention therapy, Caesarian section, and prohibiting breastfeeding. In addition, this study also described the characteristics of mothers who were diagnosed with HIV and received preventive treatment and their babies' characteristics.

The study subjects included 9 pediatric patients born from HIV-positive mothers at Korea University Ansan Hospital, between March 1, 2003 and May 31, 2013. Mothers were diagnosed with HIV on the basis of positive test results for HIV antibodies and Western blot during prenatal or preoperative tests in other hospitals and were referred to the Department of Infectious Diseases for treatment and counseling. No mothers had a history of smoking, drinking alcohol, or using medication during pregnancy. The method included a retrospective analysis of medical records of the mother-newborn dyads, including the mother's age; HIV diagnosis date; CD4+ count; HIV RNA copy numbers at the time of the first hospital visit, and first and third trimesters of pregnancy; presence of syphilis, hepatitis, or other associated diseases; history of antiretroviral therapy; type of medicine used in antiretroviral therapy and administration period; blood test results during delivery and obstetrical history; and anthropometry and blood test results of the child at birth, growth, and development as well as administered drugs. The number of HIV RNA copy and HIV antigen/antibody test results for children were analyzed within 48 hours after birth, 1-2 months, 3-6 months, and after 7 months.

The number of weeks of pregnancy was determined on the basis of the menstrual calendar and uterine fundal height through ultrasound examinations at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology. A birth earlier than 37 weeks was considered preterm, and birth weight lower than 2,500 g was considered low birth weight. The study was performed 4 hours before and after amniorrhexis. Height below the 5th percentile was considered a follow-up growth delay. Babies with a body weight below the 10th percentile for their age were considered small for gestational age. If HIV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results were negative 3 consecutive times within 6 months, the newborn was considered HIV negative.

Before July 2009, the plasma HIV RNA of newborns was tested through the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Thereafter, the tests were performed directly by the hospital. The copy number of HIV RNA in mothers and newborns were estimated using a quantitative PCR assay (AmplicorHIV-1 Monitor Test, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA).

The absolute CD4+ counts at the time of the mothers' hospital visit, and first and third trimesters of pregnancy were determined by a flowcytometer (Cytomics FC 500, Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) that uses monoclonal antibodies to calculate the total number of leukocytes and numbers of each type of lymphocyte.

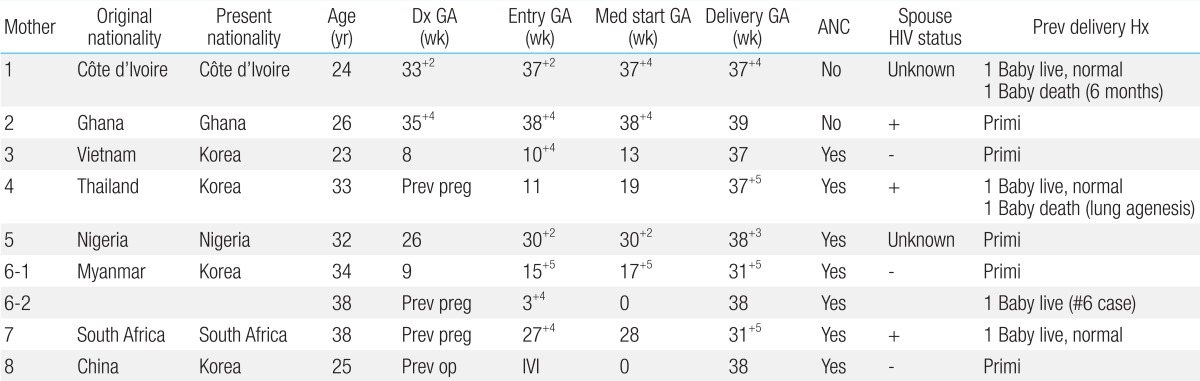

During the study period, 8 HIV-positive mothers gave birth to a total of 9 children. For 2 out of 9 children, follow-up was discontinued after release from the hospital. All 8 mothers were foreigners originally from other countries including Vietnam, Thailand, Myanmar, South Africa, Nigeria, Ghana, and Côte d'Ivoire. At the time of childbirth, 4 out of 8 mothers (50%) were aged under 30 years, while 4 (50%) were aged over 30 years; the average was 32 years, ranging from 23-38 years. Two out of 8 mothers did not receive prenatal care, while 6 received prenatal care at our hospital-2 of them after 27 weeks of pregnancy (i.e., 27 weeks 4 days and 30 weeks 4 days, respectively) (Table 1).

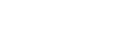

Six mothers (75%) were diagnosed with HIV on the basis of their prenatal test results. One of the remaining 2 mothers was diagnosed on the basis of a test performed before surgery for cyst removal from the skin of the buttocks and received HIV treatment at out hospital prior to pregnancy. Another mother was already aware of the diagnosis in her home country but received irregular antiretroviral treatment and did not receive treatment after entering the Republic of Korea. All 8 mothers were administered antiretroviral drugs immediately after visiting our hospital. The period of administration ranged from 1 day before delivery to starting before pregnancy, with an average of 14 weeks. One of the mothers (12.5%) was administered antiretroviral treatment before pregnancy, and 3 were administered the drugs from the second trimester (37.5%). Meanwhile, 4 mothers (50%) started treatment after 27 weeks of pregnancy (defined as late diagnosis hereafter). Three mothers (37.5%) received only zidovudine and lamivudine, which are nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs); one of them was receiving nelfinavir, a protease inhibitor (PI), but her hemoglobin according to the blood count dropped from 11.2 to 8.4 g/dL, indicating anemia. Therefore, at 25 weeks, nelfinavir was discontinued and she received only NRTI medication. The other 5 mothers (62.5%) were administered highly active antiretroviral therapy that included zidovudine, lamivudine, and PI. Two of the 8 mothers had coinfection caused by syphilis and hepatitis C virus (Table 2).

The average CD4+ count and HIV viral load of the mothers at the time of their hospital visits were 325/µL (92-729/µL) and at 2,320 HIV RNA (undetectable up to 115,280 copies/mL), respectively. For 5 mothers, viral load was confirmed before delivery and remained below 1,000 copies/mL (undetectable up to 187 copies/mL). Two mothers who did not receive prenatal care had low viral loads directly before delivery (220 and 390 copies/mL, respectively). The viral load of the remaining mother 1 month before delivery was high (2,320 copies/mL) (Table 3).

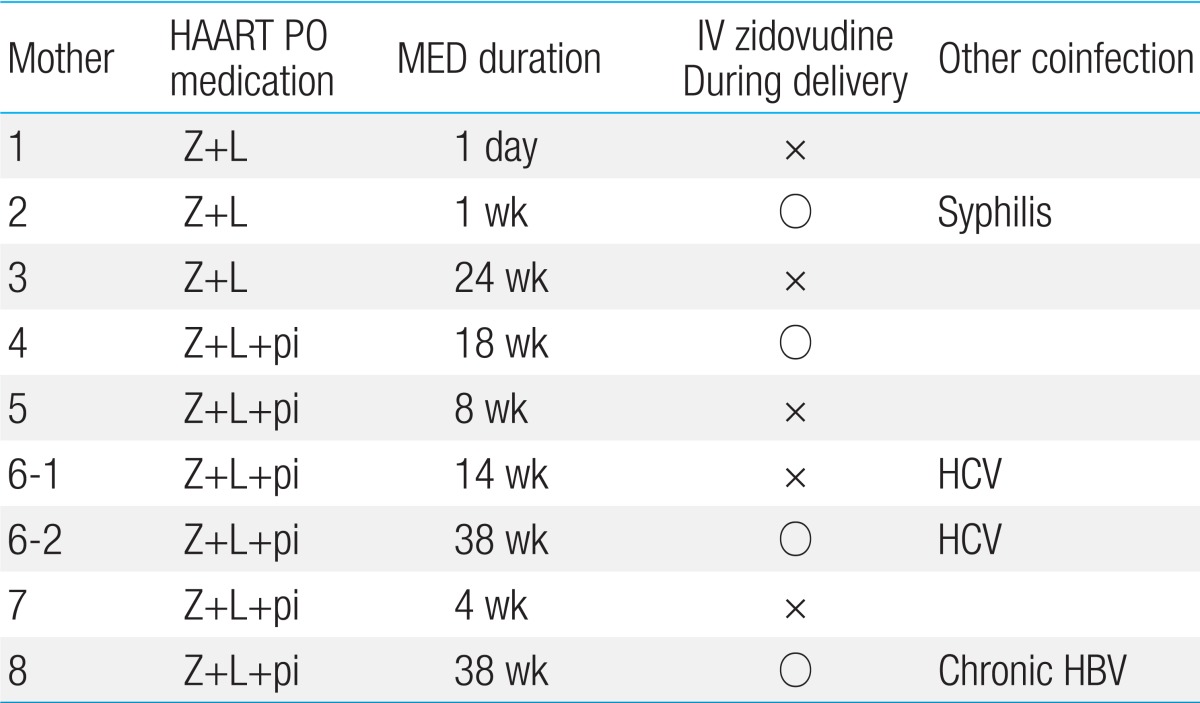

All 8 mothers received antiretroviral therapy including zidovudine prior to delivery. All 9 newborns were delivered via Caesarian section. Two newborns (22.2%) experienced early rupture of membranes; in one, this lasted over 50 hours, and another emergency Caesarian section was performed within 3 hours after membrane rupture in the other. Seven newborns were delivered via scheduled Caesarian section. Four out of 9 newborns (44.4%) received intravenous zidovudine during delivery. The remaining newborns did not receive zidovudine during delivery because it was not available in Korea until 2007. All newborns were administered zidovudine syrup at 2 mg/kg every 6 hours for 6 weeks after birth and were not breastfed by their mothers.

Two babies were preterm at 31 weeks 5 days (22.2%), and 7 babies (77.7%) were full-term born after 37 weeks of pregnancy. The average number of weeks was 37 weeks 5 days (31 weeks 5 days to 39 weeks). Three out of 9 babies (33.3%) had low birth weight; 2 of them (22.2%) were born preterm, and 1 (11.1%) was small for gestational age. The average birth weight of all babies was 2,800 g (1,728-3,400 g). All babies but one had average Apgar scores of 8±0.5 and 9.5±0.5 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The remaining baby had Apgar scores of 4 and 7 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively; it exhibited respiratory distress syndrome and required mechanical ventilation. Since congenital syphilis was suspected in the newborn whose mother was diagnosed with syphilis during prenatal care, the newborn was administered penicillin intravenously for 10 days. Pediatric patients were further monitored through the outpatient department of our hospital; except for one, none had special growth or development problems. One baby had congenital ptosis, ventricular septal defect, and growth failure and was monitored through the outpatient department (Table 4).

The HIV antigen, HIV reverse transcription-PCR, and HIV antibody tests were performed for all babies within 24 hours after birth as well as from 1-2, 3-6, and 7-12 months. Besides 2 babies (22.2%), who either returned to their home countries or for whom follow-up documents could not be retrieved from other hospitals, all babies (7, 77.7%) tested negative for HIV.

This study demonstrated that it is possible to substantially prevent HIV transmission from HIV-positive mothers to their babies by preventing intrauterine transmission through administering antiretroviral drugs to the mother, decreasing the risk of transmission during birth by performing elective Caesarian section, and encouraging giving up breastfeeding to decrease the spread of HIV through breast milk. The follow-up observation based on babies' development and blood test results show that most newborns exhibited no specific deviations in blood test results or developmental impairments. Encouraging antiretroviral therapy and preventing early membrane rupture through scheduled Caesarian section considerably decreased the HIV transmission level to children from mothers, who at the time of their first hospital visit had different HIV viral loads and CD4+ lymphocyte counts and in some cases had other accompanying diseases.

According to American statistics, between 1985 and 1998, the percentage of HIV infection in women among all cases increased from 7% to 23%, which in turn led to more infected pregnant women. Between 1993 and 1997, up to 15,000 babies born to HIV-infected mothers were themselves infected8). According to the reports of the Korea National Institute of Health, in April 2003 and 2005, 2 and 5 babies were infected via mother-to-child transmission, respectively; a total of 7cases of mother-to-child HIV transmission in Korea were reported between 1985 and 20119). In addition, 58% of women with infection were in their 20s to 40s. The continuing development of drug treatments will increase lifespan and improve quality of life. Therefore, the number of infected pregnant women is expected to increase, which in turn will result in the gradual increase of the number of newborns infected with HIV via mother-to-child transmission.

In the US, HIV infection in children occurs via mother-to-child transmission, transfusion, and the transfusion of clotting factor in 81%, 11%, and 5% of cases, respectively. Meanwhile, according to Korean data, 81% of children with HIV were infected via mother-to-child transmission and more than 80% of children with AIDS are under 5 years of age9,10,11). Accordingly, the mother-to-child route of transmission is the most common route of HIV transmission in small children and the main reason why pediatric patients worldwide contract AIDS. Mother-to-child HIV transmission can occur inside the uterus, during delivery, or through breast milk. In 30%-50% of cases, transmission occurs at the end of pregnancy, immediately before labor starts and immediately before the separation of the placenta. In approximately 30% of cases, transmission occurs after the desquamation of the placenta, when the baby is passing through the birth canal12). There is a 40% risk of infection when consuming contaminated breast milk13). Preventive measures according to the Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) protocol 076 test are reported to reduce the risk of infection by 70%, lowering the risk of mother-to-child transmission to 2%5).

Thus, it is possible to prevent more than two-thirds of mother-to-child transmission with appropriate preventive measures. The most important factor is early discovery through screening. Another study shows that antiretroviral treatment during pregnancy, labor, and delivery as well as administration of drugs to the newborn and scheduled Caesarian delivery, it is possible to decrease perinatal HIV transmission to less than 2% for mothers with high viral load (i.e., >1,000 copies/mL). It is reported that even if antiretroviral treatment is started only during labor and delivery, it is possible to decrease the risk of transmission to 10%14,15). Recent reports indicate that, unrelated to antiretroviral therapy, Caesarian section performed before labor starts and membrane rupture reduces the risk of transmission by 50% compared to natural delivery and emergency Caesarian section16,17).

Among the various theories about how antiretroviral therapy decreases perinatal transmission, the most important theory is that if the drugs are administered during pregnancy, they decrease the viral load in mother's blood and vaginal discharge, which decreases transmission to the newborn18). However, perinatal transmission has been reported even in cases with a very low or undetectable HIV viral load; this suggests there are other factors besides HIV RNA2,19). Accordingly, the US Centers for Disease Control recommends antiretroviral therapy for all HIV-positive pregnant women regardless of HIV viral load20). In this study, all mothers except one had low HIV RNA viral loads (i.e., <1,000 copies/mL) close to delivery. Besides 2 babies for whom follow-up was not possible, all babies tested negative for HIV. The transmission rate could have been low because of the decrease in viral load due to treatment in cases in which the viral load was initially high during the first hospital visit or initially low when visiting the hospital close to delivery. Only one mother had a high viral load (2,320 copies/mL) and began antiretroviral therapy after 28 weeks. In this case, emergency Caesarian section was performed because of membrane rupture; therefore, antiretroviral treatment lasted only 1 month, viral load was not measured immediately before delivery, and intravenous zidovudine was not administered. However, the newborn tested negative for HIV. This lowering of transmission risk can be attributed to the performance of emergency Caesarian section within 3 hours of membrane rupture, administration of zidovudine syrup to the newborn for 6 weeks, and absence of breastfeeding. Therefore, even if the mother tested positive for HIV, and the viral load is unregulated, other preventive methods can prevent mother-to-child transmission.

Another theory about why antiretroviral therapy in mothers decreases the risk of infection in newborns is that antiretroviral drugs administered to the mother pass through the placenta to the fetus, which is exposed to HIV, providing the fetus a certain amount of the drugs (i.e., pre-exposure prophylaxis). Many studies report that zidovudine in particular passes through the placenta and prevents the virus from proliferating in the fetal blood, thereby decreasing mother-to-child transmission21,22). Accordingly, NRTIs that cross the placental barrier are mandatory. According to the American guidelines, starting antiretroviral is more beneficial therapy when the CD4+ count is <350 cells/µL or 350-500 cells/µL than not starting it at all. If the count is >500 cells/µL, it is difficult to observe the clinical benefits of antiretroviral therapy and the adverse effects due to the toxicity of the drugs are more concerning; therefore, the treatment of pregnant women is not recommended.

However, recent studies report that administering combined antiretroviral drugs in pregnant women can lead to unfavorable outcomes in pregnancy. The European Collaborative Study and the Swiss Mother + Child HIV Cohort Study compared the rate of preterm labor between women who received antiretroviral drugs and those who did not, and corrected for CD4+ lymphocyte count and the use of illegal drugs; the results show that newborns subjected to combined antiretroviral drugs were twice as likely to be preterm23). Preterm delivery was twice as likely to occur in women who received combined antiretroviral drugs before pregnancy than women administered drugs in the third trimester of pregnancy. Single medication (mainly zidovudine) is reported to have no impact on preterm labor24). In a European collaborative study of 2,279 mothers and their newborn children, 767 mothers received combined antiretroviral drugs during their pregnancy; the risk of preterm birth before 34 weeks was 2.5 times higher in the group that received treatment during pregnancy than the group that did not and 4.4 higher in the group of women who received antiretroviral drugs both before and during pregnancy24). In contrast, the results of a study about transmission from mothers to infants show that receiving multiple antiretroviral drugs does not affect preterm labor, low birth weight, low Apgar score, or mortality ratio compared to receiving a single drug or not receiving any treatment25). Another study shows that receiving combined therapy including PI significantly increases the risk of preterm labor compared to receiving treatment that does not include PI. However, receiving treatment from the first trimester of pregnancy may be linked to disease severity, making it difficult to completely exclude this possibility26).

Two out of the 9 newborns in this study were preterm. The mother of the baby who received oxygen treatment because of respiratory distress syndrome was diagnosed late and only received the drugs for 1 month. In one case, a mother received drugs from the 19 weeks of pregnancy and had preterm labor with her first child, and subsequently received drugs from before the pregnancy and her second baby was born full-term. No follow-up was possible for the children of 2 mothers who received single-drug treatments, and their infection status was not confirmed. The mother who switched from combined drug treatment to single-drug treatment at 25 weeks had a baby who was small for gestational age and had growth impairment.

Taken together, these findings indicate the increased risk of preterm labor when administering multiple drugs needs to be acknowledged. However, if there is a high risk of mother-to-child transmission, there is no need to stop medication because of the possibility of preterm labor. On the contrary, the mother's immunity, as well as higher mortality and morbidity caused by infection in newborns, need to be considered. It is rather difficult to diagnose babies born from mothers who have HIV on the basis of the presence of immunoglobulin G antibody against HIV, which crosses the placental barrier. Although most babies born from infected mothers have HIV antibodies when they are born, only 15%-30% becomes infected. In babies who do not become infected, these antibodies disappear by 9 months; in some rare cases, they remain until 18 months. Accordingly, it is impossible to determine whether a baby is infected on the basis of HIV antibody tests until the baby is 18 months of age. The most accurate method is to test not for antibodies, but for the virus itself4).

PCR and virus culture tests are accurate, and it is possible to diagnose 30%-50% of infected children at birth and 100% by 3-6 months27). In order to determine whether a child born from an HIV-positive mother is infected, PCR and virus culture tests need to be performed at birth, 4-6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. If the result of the test performed at approximately 1 month is negative, the repeat test is performed from 3-6 months20). However, if the baby exhibits AIDS symptoms, HIV infection can be diagnosed even if the test results are negative. If the virus test performed at 6 months is negative, HIV antibodies tests are negative after 6 months, and there are no symptoms of HIV infection, it can be concluded that the baby did not contract HIV. Besides 2 patients for whom follow-up was not possible, all HIV PCR tests before 6 months and HIV antigen tests were negative; consequently, all 7 children were not diagnosed with HIV.

Infants infected via mother-to-child transmission initially present with nonspecific symptoms28). Accordingly, children must be observed continuously until HIV infection is proven negative through examination and virus tests during follow-up. In this study, antiretroviral drugs were administered before birth, during delivery, and to children after birth as suggested by the PACTG protocol 076 (1994). The 30%-50% HIV transmission rate during delivery was reduced by performing Caesarian section. Finally, the 40% rate of transmission via the breast milk was established by discouraging breastfeeding. The possibility of transmission via all possible routes was decreased. Consequently, it was possible to decrease the transmission rate of HIV from mother to child. In addition, the influences of the mother's infection status, accompanying diseases, type of antiretroviral drug, and drug administration period on the decrease in transmission rate as well as on the newborn were analyzed. No mothers in the present study were Korean, 7 were diagnosed with HIV before delivery, and 2 were already aware of their HIV infection status but were not managing the disease properly. Meanwhile, 5 mothers had foreign citizenship and were temporarily residing in Korea; they did not receive prenatal care and were diagnosed with HIV when they underwent prenatal tests in the third trimester of pregnancy for the first time. Accordingly, the biggest problem of perinatal infection is that many mothers do not know their HIV status and/or the exact degree of infection. If fertile women are tested in their first trimester, prompt treatment is possible; this not only benefits the health of the mother, but also decreases the risk of infection to their baby. In addition, the recent increases in the number of foreign workers and international marriages in Korea have increased the number of foreign residents to over 300,000; more than 50 HIV new cases are confirmed annually9,29).

The number of infected foreigners is continuing to increase, with 64 and 71 new cases in 2010 and 2011, respectively; a total of 958 people were infected with HIV by the end of 2011. Among all patients, 29.1% are women and 70.9% are men. Meanwhile, among Korean patients, 8% are women and 92% are men. Therefore, foreign women have an exceptionally higher infection rate than Korean women29). This may increase the probability of giving birth to a child infected with HIV via mother-to-child transmission. Furthermore, if counseling and screening for HIV infection prior to delivery and prevention using appropriate antiretroviral drugs are not performed, the number of children infected with HIV is expected to increase gradually.

The present study used the data of HIV-positive mothers who were foreign workers or foreign women married to Korean men and their children to confirm that antiretroviral preventive therapy, scheduled Caesarian section, and avoiding breastfeeding considerably lower the risk of their children contracting HIV via mother-to-child transmission. A limitation of this study is that it did not include a substantial amount of data on infected mothers, because there are not many people who suffer from the disease in Korea. Furthermore, the study did not confirm significant associations between many variables. However, considering the number of babies infected with HIV via mother-to-child transmission may gradually increase, similar studies in more varied regions using more varied variables should be conducted continuously.

References

1. The Working Group on Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV. Rates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Africa, America, and Europe: results from 13 perinatal studies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1995;8:506–510.

2. Sperling RS, Shapiro DE, Coombs RW, Todd JA, Herman SA, McSherry GD, et al. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. Maternal viral load, zidovudine treatment, and the risk of transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from mother to infant. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1621–1629.

3. Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme JW, Schor NF, Behrman RE. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2011.

4. Lee HJ. Pediatric HIV infection. Korean J Infect Dis 1995;27:425–437.

5. Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O'Sullivan MJ, et al. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. N Engl J Med 1994;331:1173–1180.

6. Zhou Z, Meyers K, Li X, Chen Q, Qian H, Lao Y, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 using highly active antiretroviral therapy in rural Yunnan, China. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53(Suppl 1): S15–S22.

7. Kim HY, Kasonde P, Mwiya M, Thea DM, Kankasa C, Sinkala M, et al. Pregnancy loss and role of infant HIV status on perinatal mortality among HIV-infected women. BMC Pediatr 2012;12:138

8. Lindegren ML, Byers RH Jr, Thomas P, Davis SF, Caldwell B, Rogers M, et al. Trends in perinatal transmission of HIV/AIDS in the United States. JAMA 1999;282:531–538.

9. Choe KW. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS: Current Status, Trend and Prospect. J Korean Med Assoc 2007;50:296–302.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011;:1–11.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Center for Infectious Diseases, Division of HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS surveillance. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of HIV/AIDS, 1993.

12. Kourtis AP, Lee FK, Abrams EJ, Jamieson DJ, Bulterys M. Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1: timing and implications for prevention. Lancet Infect Dis 2006;6:726–732.

13. Coovadia H. Current issues in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2009;4:319–324.

14. Mofenson LM. Committee on Pediatric Aids. Technical report: perinatal human immunodeficiency virus testing and prevention of transmission. Pediatrics 2000;106:E88

15. Read JS, Newell MK. Efficacy and safety of cesarean delivery for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4): CD005479

16. European Mode of Delivery Collaboration. Elective caesarean-section versus vaginal delivery in prevention of vertical HIV-1 transmission: a randomised clinical trial. Lancet 1999;353:1035–1039.

17. Landesman SH, Kalish LA, Burns DN, Minkoff H, Fox HE, Zorrilla C, et al. The Women and Infants Transmission Study. Obstetrical factors and the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from mother to child. N Engl J Med 1996;334:1617–1623.

18. Garcia PM, Kalish LA, Pitt J, Minkoff H, Quinn TC, Burchett SK, et al. Women and Infants Transmission Study Group. Maternal levels of plasma human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and the risk of perinatal transmission. N Engl J Med 1999;341:394–402.

19. Cooper ER, Charurat M, Mofenson L, Hanson IC, Pitt J, Diaz C, et al. Combination antiretroviral strategies for the treatment of pregnant HIV-1-infected women and prevention of perinatal HIV-1 transmission. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2002;29:484–494.

20. Perinatal HIV Guidelines Working Group. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Pregnant HIV-1 Infected Women for Maternal Health and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmis sion in the United States. April 29, 2009:1-90 [Internet]. Rocville (MD): AIDS Info, c2014;cited 2013 Jun 30. Available from: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/PerinatalGL.pdf.

21. Jackson JB, Musoke P, Fleming T, Guay LA, Bagenda D, Allen M, et al. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: 18-month follow-up of the HIVNET 012 randomised trial. Lancet 2003;362:859–868.

22. Moodley D, Moodley J, Coovadia H, Gray G, McIntyre J, Hofmyer J, et al. A multicenter randomized controlled trial of nevirapine versus a combination of zidovudine and lamivudine to reduce intrapartum and early postpartum mother-to-child transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis 2003;187:725–735.

23. European Collaborative Study. Swiss Mother and Child HIV Cohort Study. Combination antiretroviral therapy and duration of pregnancy. AIDS 2000;14:2913–2920.

24. Thorne C, Patel D, Newell ML. Increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in HIV-infected women treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy in Europe. AIDS 2004;18:2337–2339.

25. Tuomala RE, Watts DH, Li D, Vajaranant M, Pitt J, Hammill H, et al. Improved obstetric outcomes and few maternal toxicities are associated with antiretroviral therapy, including highly active antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;38:449–473.

26. Rudin C, Spaenhauer A, Keiser O, Rickenbach M, Kind C, Aebi-Popp K, et al. Antiretroviral therapy during pregnancy and premature birth: analysis of Swiss data. HIV Med 2011;12:228–235.

27. Barret B, Tardieu M, Rustin P, Lacroix C, Chabrol B, Desguerre I, et al. Persistent mitochondrial dysfunction in HIV-1-exposed but uninfected infants: clinical screening in a large prospective cohort. AIDS 2003;17:1769–1785.

28. Soh YM. HIV Infection in Children. J Korean Pediatr Soc 1995;38:1023–1035.

29. Chung YH, Cho SS. Analysis of HIV/AIDS notifications in Korea, 2011. Public Health Wkly Rep 2012;5:813–818.

Table 1

Characteristics of the mothers infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Dx GA, gestational age at the time of diagnosis; GA, gestational age; Entry GA, gestational age at the time of entry in hospital; Med start GA, gestational age at the time of starting antiretroviral medication; Delivery GA, gestational age at the time of delivery; ANC, antenatal care; Prev delivery Hx, previous delivery history; Primi, primigravida; Prev preg, previous pregnancy before present pregnancy; Prev op, previous operation before present pregnancy; IVI, intravaginal insemination.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation