Article Contents

| Clin Exp Pediatr > Volume 65(3); 2022 |

|

Abstract

Background

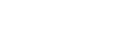

Individuals with Down syndrome present with several impairments such as hypotonia, ligament laxity, decreased muscle strength, insufficient muscular cocontraction, inadequate postural control, and disturbed proprioception. These factors are responsible for the developmental challenges faced by children with Down syndrome. These individuals also present with balance dysfunctions.

Purpose

This systematic review aims to describe the motor dysfunction and balance impairments in children and adolescents with Down syndrome.

Methods

We searched the Scopus, ScienceDirect, MEDLINE, Wiley, and EBSCO databases for observational studies evaluating the motor abilities and balance performance in individuals with Down syndrome. The review was registered on PROSPERO.

Results

A total of 1,096 articles were retrieved; after careful screening and scrutinizing against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 10 articles were included in the review. Overall, the children and adolescents with Down syndrome showed delays and dysfunction in performing various activities such as sitting, pulling to stand, standing, and walking. They also presented with compensatory mechanisms to maintain their equilibrium in static and dynamic activities.

Conclusion

The motor development of children with Down syndrome is significantly delayed due to structural differences in the brain. These individuals have inefficient compensatory strategies like increasing step width, increasing frequency of mediolateral center of pressure displacement, decreasing anteroposterior displacement, increasing trunk stiffness, and increasing posterior trunk displacement to maintain equilibrium. Down syndrome presents with interindividual variations; therefore, a thorough evaluation is required before a structured intervention is developed to improve motor and balance dysfunction.

Graphical abstract. Gross motor dysfunction and balance impairment in children with Down syndrome

Down syndrome, the most common genetic disorder, leads to pathological disturbances, characterized by physical and mental alterations [1]. The common impairments include hypotonia, ligament laxity, decreased muscle strength, insufficient cocontraction of muscles, inadequate postural control, disturbed proprioception, short stature, and cognitive impairment [2,3]. These factors characterize the significant challenges faced by children and adolescents with Down syndrome [2].

Motor development, being a dynamic process, consists of neither a beginning nor an end, nor does it occur at a specific age [4]. A few studies claim that children with Down syndrome attain their motor milestones 2 times later than typically developing children [2,5]. A study by Riquelme Agulló et al. [4] concludes that children with Down syndrome showed a delay in achieving gross motor milestones such as reaching, sitting, crawling, and walking compared to typically developing children who acquire these skills during their first year of life. These motor dysfunctions lead to limited physical activity causing a developmental delay in various domains [6].

The ability to maintain equilibrium in sitting and standing serves as an essential predictor of the individual's safety, independence, and quality of life [6]. Static and dynamic balance is crucial to maintain a stable posture and perform different activities of daily living [6]. Jung et al. [6] concluded that balance is the most severely affected domain in children and adolescents with Down syndrome out of all the functional impairments studied. According to another study, there is a direct correlation between sitting balance and quality of upper limb activities in the population with Down syndrome [7-9].

In the last decade, there has been a significant paradigm shift in the field of rehabilitation, from addressing only the impairments to focusing on maximizing an individual’s independence. This shift has mainly occurred due to the in-depth understanding of the syndrome and development of new treatment approaches along with the availability of modern technology required to cater to the needs of children with Down syndrome. A detailed understanding of the development, the mechanism of impairments, and their effect on functions will help us achieve this paradigm shift. Owing to the above considerations, it is of paramount importance to clearly and intricately understand the knowledge regarding the development and compensatory strategies used by children with Down syndrome for performing motor functions and maintaining balance to help in sculpting and formulating an appropriately structured intervention strategy. There is existing knowledge to highlight the above points but there is also paucity in the amplitude of research as well as inconsistent and variable results. Hence, the purpose of the present systematic review is to assimilate the data available and describe the gross motor dysfunction, the static and dynamic balance impairments along with the compensatory mechanisms secondary to poor balance amongst the children and adolescents with Down syndrome.

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO).

Two reviewers conducted a systematic search in 5 electronic databases (Scopus, PubMed, ScienceDirect, Wiley, EBSCO) till May 2020 for original articles using the following keywords: Motor activity, Gross motor function, Motor performance, Motor function, Motor skill, Balance, Postural balance, Down syndrome. These keywords were searched alone or in combination in title-abstract-keywords of the articles published by the journals indexed in the above-mentioned databases. The search strategy used in PubMed is given in Table 1. The same search strategy was used in all the other databases. References of the identified studies were also hand-searched to eliminate the possibility of any missed articles.

After the preliminary search, the duplicates were removed and the 2 reviewers independently screened the articles based on the title's appropriateness and adherence to the inclusion criteria.

Studies in the present review met the following inclusion criteria: (1) participants diagnosed with Down syndrome, (2) articles assessing either one or both the outcomes (motor function, balance), (3) articles published in the English language in peer-reviewed journals, (4) observational study, (5) full-text availability, and (6) articles evaluating children and adolescents with Down syndrome. Data of participants aged 5 to 18 years were included in this review. Any disagreement in the screening process was resolved by discussion and consensus between the reviewers.

Data about the authors, study design, sample characteristics, results, and limitations were extracted by the 2 reviewers from the articles which fit the eligibility criteria. Microsoft Excel was used to extract the required data. Any discrepancies were tackled by discussing them with the other reviewers.

This systematic review used a PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcomes) framework to describe the search strategy efficiently. The population included here were children and adolescents with Down syndrome. The criteria used as outcomes were evaluation of motor function or balance or both in observational studies published in English in the last 10 years.

Two blinded assessors performed National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NIH) quality assessment tool for observational, cohort, and cross-sectional studies. Any disagreement between the judgments was resolved by discussion and coming to a consensus. As the tool failed to provide a cut off range to grade the articles, the cutoffs set for this review were set as follows: (1) articles scoring > 70% - good, (2) articles scoring between 50%–70% - fair, and (3) articles scoring < 50% - poor.

Any disagreements between the reviewers were discussed and a consensus decision was reached.

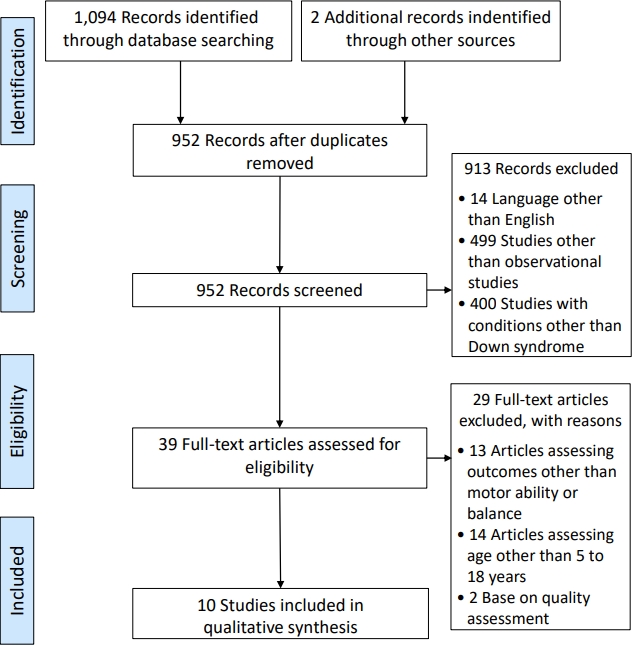

During the initial search, 1,094 articles were retrieved along with 2 articles from miscellaneous sources, of which 144 were eliminated for being duplicated in different databases. After screening the titles and abstracts of 952 articles, 913 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. 499 articles were nonobservational studies, 400 articles assessed children with disorders or syndromes other than Down syndrome and 14 articles were in languages other than English. Assessment of 39 full-text articles was carried out, and 29 articles were excluded because of the following reasons; they did not include the outcome measures of interest, the age of subjects included was less than 5 or more than 18 years, and the articles presented with poor methodological quality.

A total of 10 articles met the inclusion criteria and underwent the data extraction process. (Fig. 1 represents PRISMA flowchart for study selection).

All the 10 studies included in this systematic review are cross-sectional studies, published in the last 10 years in English. All of them represent level IV evidence. The characteristics of the included studies are expressed in Table 2.

Of the 10 studies, 6 studied motor function, 2 studied balance function, and 2 studied motor as well as balance function in children and adolescents with Down syndrome as the primary outcome. Motor function was assessed using Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM), Bruininks-Oseretsky Test of Motor Proficiency (BOTMP), Test of Gross Motor Development 2nd edition (TGMD-2), Movement Assessment Battery for Children – Checklist (MABC-C), and McCarthy Scales of Children’s Ability (MSCA). Among the 4 studies assessing balance function, 1 study evaluated only static balance whereas 2 studies evaluated static as well as dynamic balance function, and 1 study assessed functional balance. Balance function was assessed using a force platform and Pediatric Balance Scale (PBS).

A total of 680 children and adolescents with Down syndrome and 124 typically developing individuals between the age of 5 to 18 years were included in these studies. Based on the age range and mean age, 4 studies included children (age, 5–9 years), 2 studies included adolescents (age, 10–18 years), and 4 studies consisted of children as well as adolescents. Of these 680 children and adolescents with Down syndrome, motor function was assessed in 400 children and 234 adolescents, static balance in 14 children and 55 adolescents, dynamic balance in 14 children and 23 adolescents, and functional balance in 79 children. All the participants were recruited from either school for special children, rehabilitation centers, or foundations.

All individuals diagnosed with Down syndrome by a pediatrician, with an understanding of simple instructions for measurement procedure, and without any musculoskeletal, visual, hearing, or perceptual problems that restricted assessment was included in all the 10 studies. Only 2 studies that assessed motor function included intelligence quotient in their inclusion criteria which were set as 50–70. The inclusion criteria for 2 articles assessing balance function and 2 articles assessing both i.e., balance and motor function consisted of individuals with independent standing and walking abilities.

A variety of assessment tools were used to measure the outcome of interest. Motor function was studied using GMFM in 2 studies, TGMD-2 in 1 study, MABC-C in 1 study, TGMD-2 and MABC-C in 2 studies, GMFM and BOTMP in 1 study, and MSCA in 1 study. Three studies that used GMFM to measure motor function used 2 dimensions, i.e., standing and walking/running/jumping out of 5 dimensions.

The second outcome, balance, was assessed using force platform in 3 studies and PBS in 1 study. Data regarding the static and dynamic balance function using the force platform was presented by the center of pressure excursions. Center of pressure excursion evaluates the sway of the body in terms of amplitude and velocity, measuring in 3 dimensional (x, y, z) forces and the pressure sensors on the force plate measures the change in the pressure over the plantar surface of the foot during stance [10]. Additionally, reaction time and execution time were also measured to estimate the delay in performing a movement following the command while maintaining standing balance and the total time taken to complete the entire task at hand, respectively [11]. For static balance, the measurements were taken in an upright standing position, barefoot with arms by the side and feet positioned 30o relative to each other and heels 5 cm apart for 30 seconds. One study assessed dynamic balance function by recording center of pressure measurements while the participants stand in natural stance on the force platform and throw a ball. In the second study that assessed dynamic balance, the force plate recorded the center of pressure while performing reach at 3 distances, i.e., 80%, 100%, and 120% of arm distance. While performing this, 3-dimensional kinematics of the reaching arm with retroreflective markers placed on the arm was also recorded using a 6-camera motion capture system. One study used PBS, a valid measure to assess the functional balance.

The methodological assessment was performed using the NIH assessment tool for observational, cohort, and cross-sectional studies (Table 3). A score of more than 50% was essential for inclusion in this review. Based on this, 2 articles were excluded. All the articles in this systematic review had a cross-sectional study design and were graded as either fair or good using NIH assessment tool. Five studies were graded as fair and 5 as good. Four out of 8 studies which assess motor function were graded as good while 4 studies were graded as fair. One study that assessed only static balance using force platform was graded as fair. Among the 2 studies which assessed static as well as dynamic balance using force platform, 1 was graded as fair and the other as good. Article studying functional balance using PBS was graded as fair.

There is an extensive delay in the developmental skills in children with Down syndrome compared to typically developing children [12]. The delay is due to structural differences in the brain, like reduction in the volume of grey and white matter of the cerebellum, frontal lobes, parietal lobes, corpus callosum, and hippocampus, along with a delay in central and peripheral neural myelination [13-15]. Because of these structural changes, various neuromuscular and musculoskeletal deviations occur in children and adolescents with Down syndrome [14]. Defects in the cerebrum, corpus callosum, cerebellum, and brainstem among the children with Down syndrome could be a reason for the significant developmental delay [14]. Hypoplasia of the cerebellum and corpus callosum is one of the major factor responsible for muscle hypotonia, decreased fluency of movement and axial control, incoordination, atypical laterality, and balance abilities.2,14) Hypotonia is a cause of tendon laxity affecting the stability of the joint [14,16]. Along with this, muscle weakness, dysfunction in sensory integration processes, hypoplasia of cartilage, and impaired bone density leads to improper cocontraction of muscles [14]. According to the literature, chronologically 8-year-old children with Down syndrome present with a developmental age of 4 years, and none of the children below 6 years of age develop 100% of the motor functions on GMFM [12,14]. Rolling is the only activity that children with Down syndrome perform within 6 months of age [16]. However, sitting is delayed and it may take as long as 18 months to sit independently [14]. The probability of independent standing at 2 years in children with Down syndrome is less than 50% and, the majority of them learn to stand between 3 and 4 years of age [12,14]. Scott et al. [16] noticed a significant delay in GMFM Dimension D in children with Down syndrome including, motor abilities like running, hopping, jumping horizontally, catching, kicking, and overhead throwing. The probability of achieving running, climbing stairs, and jumping forward by 4 years of age is only 18%–25%, and by 6 years of age, the probability ranges between 65%–85% [12]. Along with the quantitative delay, children with Down syndrome display qualitative differences, such as slowness and clumsiness compared to typically developing children [7,17]. A critical component of the development is locomotion, and walking being the chief mode for children and adolescents to perform activities of daily living independently, displays a significant delay and disruption [13,14].

During quiet standing, children with Down syndrome show wider step width, but not large medial-lateral sway, unlike adolescents who present with greater center of pressure displacements in both the anteriorposterior and in medial-lateral directions along with a greater sway path [18,19]. Children with Down syndrome are incapable of adjusting their center of pressure from side to side without losing balance and hence, they use wider step width to gain more stability to maintain static balance whereas, adolescents with Down syndrome try to correct and recorrect their center of pressure at a faster rate by increasing oscillations in medial-lateral direction to compensate for their poor balance [18,19]. In general, the Down syndrome group present with an inefficient postural strategy compared to the typically developing group [18]. These strategies are not only seen while maintaining static balance but also while performing dynamic activities to maintain equilibrium [20].

Malak et al. [14] explained that standing and walking were the most difficult tasks for children with Down syndrome to attain due to the inadequate cocontraction of flexor and extensor muscle groups required to maintain the equilibrium. Consequently, children with Down syndrome start walking at 3 years of age with greater instability and increasing energy cost [14]. This leads to early fatigue and a reduced level of fitness, interfering with the development of muscle strength and endurance needed to perform movements during play and recreation [13]. Moreover, the dynamic play activities that the children and adolescents are engaged in require greater stability and hence, are significantly affected in children and adolescents with Down syndrome [16,21]. Additionally, there is a known influence of motor function on balance ability because limited movement leads to difficulty in maintaining equilibrium [14].

Children and adolescents with Down syndrome present with an increased reaction time to maintain equilibrium while performing dynamic balance activities due to delayed myelination when compared to the typically developing group [14,20]. Wang et al. found that they also exhibited a greater postural sway in the medial-lateral direction to sustain their dynamic balance, a strategy similar to control their static balance [18,19,22]. Along with this, smaller anteriorposterior sway was also noticed to compensate for the poor balance [22]. Similarly, another author noticed that when children with Down syndrome performed reaching, the medial-lateral center of pressure displacement significantly increased, whereas anteriorposterior center of pressure displacement decreased, especially while reaching beyond arm’s length [21]. Along with these strategies, there are other postural strategies that children and adolescents with Down syndrome used to compensate for their poor postural control like increasing posterior displacement and trunk stiffening [21,23].

While maintaining dynamic balance, an increase in posterior displacement is noticed to gain momentum towards the reaching target [20]. Trunk stiffening strategy is adopted to localize the progression of their forward movement and control the higher degrees of freedom necessary to simplify the intersegmental coordination required to complete a task [20,22]. These strategies adopted may be due to the insufficient coordination of their body momentum with the anticipated sway movements while performing the task, which is dependent on the extent of motor ability [22]. Often, these motor strategies adapted by children and adolescents with Down syndrome appear to influence balance negatively, that is, it increases the risk of fall which restricts their participation in community affecting their quality of life [12,20,23].

The present systematic review reveals that children and adolescents with Down syndrome experience noticeable dysfunction in their motor function and postural balance as compared to their typically developing peers due to structural, neuromuscular, and musculoskeletal changes owing to the chromosomal abnormality, which in turn limits an individual’s participation in the community and predisposes to falls. They start walking after 3 years of age, with greater instability and energy expenditure. Along with this, due to their altered ability to maintain equilibrium, they develop compensatory strategies like increased step width, increased medial-lateral center of pressure displacement frequency, and decreased anteriorposterior center of pressure displacement. These inefficient strategies seem to increase with the increasing dynamicity of the movement, including an increase in posterior displacement and trunk stiffening while performing a dynamic task. Hence, the present systematic review concludes that motor function and balance can be crucial parameters to be used as outcomes to design an effectively structured rehabilitation program for children and adolescents with Down syndrome to improve their quality of life.

The findings regarding the balance function should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size of the individual studies that met the inclusion criteria. Consequently, the studies used a variety of standardized assessment tools to measure the outcome of interest due to which a meta-analysis was not possible. The majority of studies used typically developing children and adolescents as the control group and failed to compare children and adolescents with Down syndrome to the intellectually matched group. Given this review's limitation, additional studies are required to assess the quality of motor and balance functions in this population.

Fig. 1.

The study selection process shown in a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flowchart.

Table 1.

Search strategy used in the PubMed database

Table 2.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Study design | Sample diagnosis (n) | Age range (yr) | Outcome measure | Assessment tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. [22] (2012) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=23), TD (n=23) | 8.4–19 | Motor function | Force plate (while throwing a ball) |

| Static and Dynamic Balance function | Gross Motor Function Measure (GMFM) | ||||

| Bruininks-Oseretsky Test for Motor | |||||

| Proficiency 2nd edition (BOTMP-2) | |||||

| Schott et al. [16] (2014) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=18), TD (n=18) | 7–11 | Motor function | Test of Gross Motor Development 2nd edition (TGMD-2) |

| Movement Assessment Battery – Checklist | |||||

| Malak et al. [14] (2015) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=79) | 6.3±4.6 | Motor function | GMFM |

| Functional Balance | Pediatric Balance Scale | ||||

| Schott and Holfelder [15] (2015) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=18), TD (n=18) | 7–11 | Motor function | TGMD-2 |

| Movement Assessment Battery for Children 2nd edition (MABC-2) | |||||

| Trail making test for young children (Trails-P) | |||||

| Alesi et al. [13] (2018) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=18), BIF (n=18), TD (n=18) | Group 1: 8.22±2.82 | Motor function | Test of Gross Motor Development (TGMD-Test) |

| Group 2: 9.32±0.61 | |||||

| Group 3: 9.28±0.81 | |||||

| El-Hady et al. [23] (2018) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=70) | 8–12 | Motor function | GMFM |

| Marchal et al. [21] (2016) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=123) | 10.7 | Motor function | Bayley Scale of Infant and Toddler Development-III |

| MABC-2 | |||||

| Villarroya et al. [19] (2012) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=32), TD (n=33) | 10–19 | Static balance | Force plate |

| Chen et al. [20] (2015) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=14), CG (n=14) | 8.26±0.82 | Static and dynamic balance | Force plate |

| Motion capture system | |||||

| van Gameren-Oosterom et al. [12] (2011) | Cross-sectional study | DS (n=285) | 7.8–9.1 | Motor function | McCarthy Scales of Children’s Ability |

Table 3.

National Institutes of Health assessment tool used to examine the included observational, cohort, and cross-sectional studies

| Criteria | Wang et al. [22] (2012) | Schott et al. [16] (2014) | Malak et al. [14] (2015) | Schott and Holfelder [15] (2015) | Alesi et al. [13] (2018) | El-Hady et al. [23] (2018) | Marchala et al. [21] (2016) | Villarroya et al. [19] (2012) | Chen et al. [20] (2015) | van Gameren-Oosterom et al. [12] (2011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%? | CD | CD | CD | CD | CD | CD | CD | CD | CD | CD |

| 4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants? | ||||||||||

| 5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided? | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)? | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time? | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants? | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| 13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Total | 6/10 | 7/10 | 6/10 | 7/10 | 6/10 | 6/10 | 7/10 | 6/10 | 7/10 | 7/10 |

| Percentage (%) | 60 | 70 | 60 | 70 | 60 | 60 | 70 | 60 | 70 | 70 |

| Interpretation | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Fair | Good | Fair | Good | Good |

References

1. Tudella E, Pereira K, Basso RP, Savelsbergh GJP. Description of the motor development of 3–12 month old infants with Down syndrome: the influence of the postural body position. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32:1514–20.

2. Beqaj S, Jusaj N, Živković V. Attainment of gross motor milestones in children with Down syndrome in Kosovo - developmental perspective. Med Glas (Zenica) 2017;14:189–98.

3. Winders P, Wolter-Warmerdam K, Hickey F. A schedule of gross motor development for children with Down syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 2019;63:346–56.

4. Riquelme Agulló I, Manzanal González B. Factors influencing motor development in children with Down syndrome. Int Med Rev Down Syndr 2006;10:18–24.

5. Frank K, Esbensen AJ. Fine motor and self-care milestones for individuals with Down syndrome using a retrospective chart review. J Intellect Disabil Res 2015;59:719–29.

6. Jung HK, Chung E, Lee BH. A comparison of the balance and gait function between children with Down syndrome and typically developing children. J Phys Ther Sci 2017;29:123–7.

7. de Campos AC, Rocha NA, Savelsbergh GJ. Development of reaching and grasping skills in infants with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil 2010;31:70–80.

8. Adair B, Said CM, Rodda J, Morris ME. Psychometric properties of functional mobility tools in hereditary spastic paraplegia and other childhood neurological conditions. Dev Med Child Neurol 2012;54:596–605.

9. Russell D, Palisano R, Walter S, Rosenbaum P, Gemus M, Gowland C, et al. Evaluating motor function in children with Down syndrome: validity of the GMFM. Dev Med Child Neurol 1998;40:693–701.

10. Goetschius J, Feger MA, Hertel J, Hart JM. Validating center-of-pressure balance measurements using the MatScan® pressure mat. J Sport Rehabil 2018;Jan 1 2(1): https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2017-0152. [Epub].

11. Palomo-Carrión R, Bravo-Esteban E, Ando-La Fuente S, López-Muñoz P, Martínez-Galán I, Romay-Barrero H. Efficacy of the use of unaffected hand containment in unimanual intensive therapy to increase visuomotor coordination in children with hemiplegia: a randomized controlled pilot study. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2021;12:20406223211001280.

12. van Gameren-Oosterom HB, Fekkes M, Buitendijk SE, Mohangoo AD, Bruil J, Van Wouwe JP. Development, problem behavior, and quality of life in a population based sample of eight-year-old children with Down syndrome. PLoS One 2011;6:e21879.

13. Alesi M, Battaglia G, Pepi A, Bianco A, Palma A. Gross motor proficiency and intellectual functioning: a comparison among children with Down syndrome, children with borderline intellectual functioning, and typically developing children. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e12737.

14. Malak R, Kostiukow A, Krawczyk-Wasielewska A, Mojs E, Samborski W. Delays in Motor Development in Children with Down Syndrome. Med Sci Monit 2015;21:1904–10.

15. Schott N, Holfelder B. Relationship between motor skill competency and executive function in children with Down’s syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 2015;59:860–72.

16. Schott N, Holfelder B, Mousouli O. Motor skill assessment in children with Down Syndrome: relationship between performance-based and teacher-report measures. Res Dev Disabil 2014;35:3299–312.

17. Vimercati SL, Galli M, Stella G, Caiazzo G, Ancillao A, Albertini G. Clumsiness in fine motor tasks: evidence from the quantitative drawing evaluation of children with Down Syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 2015;59:248–56.

18. Rigoldi C, Galli M, Mainardi L, Crivellini M, Albertini G. Postural control in children, teenagers and adults with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32:170–5.

19. Villarroya MA, González-Agüero A, Moros-García T, de la Flor Marín M, Moreno LA, Casajús JA. Static standing balance in adolescents with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil 2012;33:1294–300.

20. Chen HL, Yeh CF, Howe TH. Postural control during standing reach in children with Down syndrome. Res Dev Disabil 2015;38:345–51.

21. Marchal JP, Maurice-Stam H, Houtzager BA, Rutgers van Rozenburg-Marres SL, Oostrom KJ, Grootenhuis MA, et al. Growing up with Down syndrome: development from 6 months to 10.7 years. Res Dev Disabil 2016;59:437–50.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation