Article Contents

| Clin Exp Pediatr > Volume 66(6); 2023 |

|

Abstract

Background

In clinical practice, the importance of interactive engagement behaviors is overlooked in children with developmental problems other than autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Parenting stress affects children’s development but lacks attention from clinicians.

Purpose

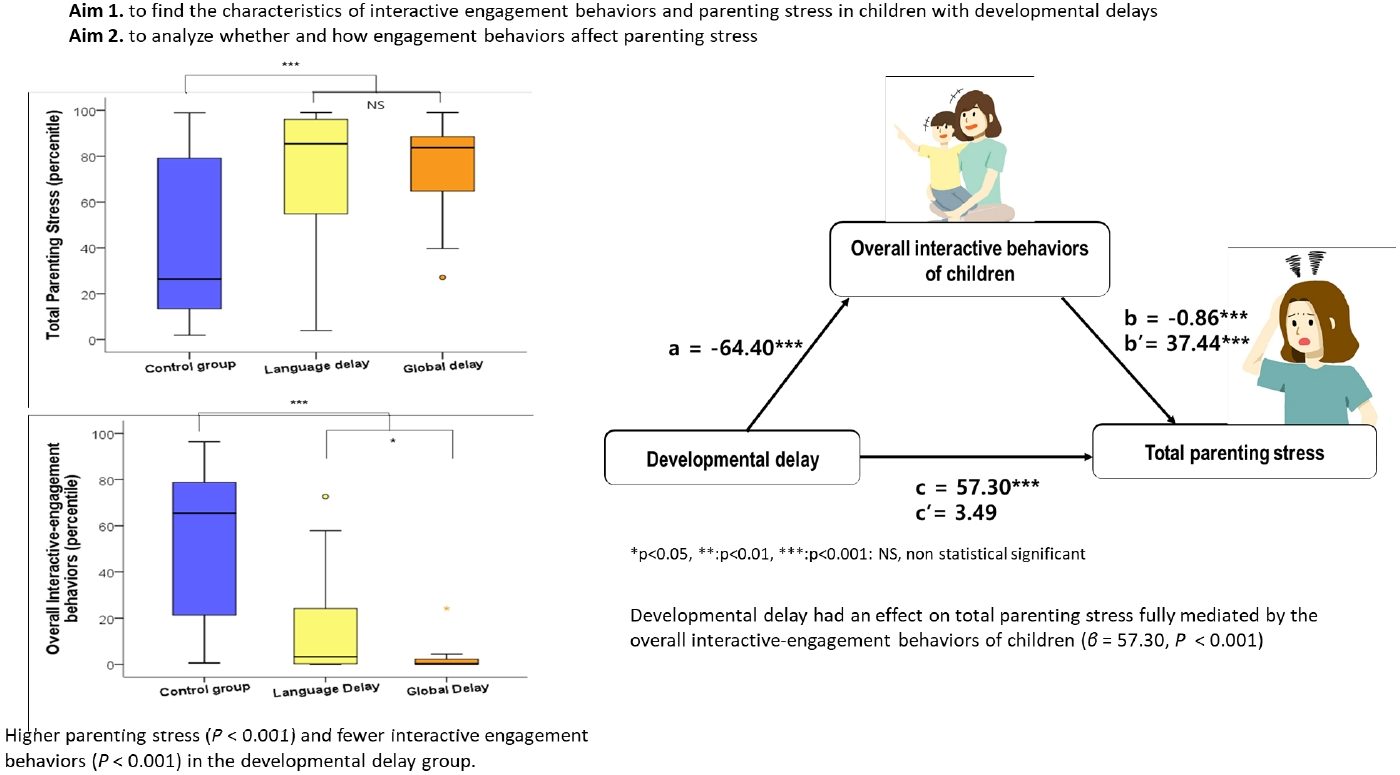

This study aimed to identify the characteristics of interactive engagement behaviors and parenting stress among non-ASD children with developmental delays (DDs). We also analyzed whether engagement behaviors affect parenting stress.

Methods

At Gyeongsang National University Hospital, between May 2021 and October 2021, we retrospectively enrolled 51 consecutive patients diagnosed with DDs in language or cognition (but not ASD) in the delayed group and 24 typically developing children in the control group. The Korean version of the Parenting Stress Index-4 and Child Interactive Behavior Test were used to assess the participants.

Results

The median age of the delayed group was 31.0 months (interquartile range, 25.0–35.5 months); this group included 42 boys (82.4%). There were no intergroup differences in child age, child sex, parental age, parental educational background, mother’s employment status, or marital status. Higher parenting stress (P<0.001) and fewer interactive engagement behaviors (P<0.001) were observed in the delayed group. Low parental acceptance and competence had the largest effects on total parenting stress in the delayed group. A mediation analysis revealed that DDs did not directly affect total parenting stress (β=3.49, P=0.440). Instead, DDs contributed to total parenting stress, which was mediated by children’s overall interactive engagement behaviors (β=57.30, P<0.001).

Graphical abstract.

Parenting stress can be defined as the parental perception of a discrepancy between the demands of parenting and available resources [1]. Parents of children with developmental disabilities experience higher parenting stress than those of children without these comorbidities [2]. A significant association between parenting stress and behavioral problems has been reported regardless of the presence or absence of developmental disabilities [3,4]. Children with developmental disabilities exhibit more challenging behaviors than those without such conditions [4]. Thus, parents of children with developmental disabilities experience a high parenting burden due to their child’s developmental deficit and the accompanying challenging behaviors [5]. Some researchers have reported that the extent of behavioral issues is a much stronger contributor to parenting stress than the child’s cognitive delay [4]. It is not possible for parents to avoid experiencing some degree of parenting stress. However, when parents perceive a high level of parenting stress, they may become less responsive to their child’s needs, resulting in punitive or negligent parenting behavior [6,7]. These negative parenting behaviors, in turn, have an adverse impact on a child’s development [8]. Thus, it is necessary to understand the parenting stress faced by parents of children with developmental delays (DDs) and to formulate interventions to promote the child’s development.

Many studies have defined the challenging behaviors of young nfants and children as problem behaviors based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-oriented scales such as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [4,7,9]. However, it may not be suitable to label the challenging behaviors observed in young infants and children whose brains are still maturing as problem behaviors. The various challenging behaviors observed in children with DDs may be byproducts of delayed acquisition of social, emotional, and communication skills. Young infants and children learn and develop by participating in engagement activities with others, particularly parents [10]. From the beginning of life, children build relationships with their parents as partners in turn-taking interactions [11,12]. Engagement behaviors, such as preference of human-related stimuli and eye contact/tracking, are prerequisites for reciprocal interactions with others [10]. Mahoney et al. [10] reported that the frequency with which children exhibited engagement behaviors (i.e., attention, initiation, persistence, interest, cooperation, joint attention, and affect) was significantly associated with the children’s social, communication, and cognitive development.

Deficits in these behaviors, commonly observed in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), act as major barriers to cognitive, language, and social development or learning [13]. In children with various developmental problems, the lower the interactive engagement behaviors, the lower the child’s developmental status [10]. Researchers comparing young children aged 3–5 years with and without DDs showed that socially withdrawn behavioral patterns were 4 times more likely in children with DDs [14]. However, clinicians appear less interested in interactive engagement behaviors in children with developmental problems other than ASD. A meta-analysis showed that parents of children with ASD perceived greater parenting stress than those with other disabilities [15]. These findings suggest that the core symptoms of ASD, which include difficulties in social interaction and social communicative engagement may have a great impact on parenting stress [16]. However, there are limited data on the effects of interactive engagement behaviors of non-ASD children with developmental problems on parenting stress.

The primary aim of this study was to compare the characteristics of interactive engagement behaviors and parenting stress in non-ASD children with DDs with those in children with typical development. We then analyzed whether and how interactive engagement behaviors affected parenting stress.

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of consecutive patients who visited the outpatient pediatric clinic of a tertiary medical center in Korea to undergo assessments for DDs from May 2021 to December 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged between 12 and 43 months; (2) diagnosed with a delay in language and/or cognition; and (3) completed a questionnaire on parenting stress and interactive engagement behaviors. A DD was defined as a composite score of <85 in the cognition or language domains of the Bayley Scales of Infants and Toddlers Development-III (Bayley-III). Children with DDs were categorized into the delayed group. The delayed group was further divided into a language delay group and a global delay group (delay in both language and cognition) for enabling analysis based on the type of DD. All patients referred to the clinic due to DDs were evaluated using the Korean Childhood Autism Rating Scale, and those with a total score of ≥28 were excluded from the study.

Children aged 12–43 months who visited the hospital during the same period for acute illness such as febrile seizures with normal development were enrolled as the control group. Development in the control group was screened using the Korean Developmental Screening Test for Infants and Children (K-DST).

Demographic data included the child’s age, sex, parents’ age, parents’ education, mothers’ employment, and marital status.

The Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition (PSI-4) was used to assess parenting stress [1]. The PSI-4 is a 120-item inventory that is widely used to measure parenting stress and functioning with reference to children aged between 1 month and 12 years. This questionnaire focuses on 3 major domains of stress: child domain, parent domain, and life stress domain [1]. The child domain measures the characteristics of the child that make parenting difficult and includes distractibility/hyperactivity, adaptability, reinforces parent, demandingness, mood, and acceptability. The parent domain measures the characteristics of the parent and family, which can result in stress and parental dysfunction. Competence, isolation, attachment, health, role restriction, and spouse relationship are included in this domain. The life stress domain includes 19 dichotomous items to assess the personal experiences of the parent within the past 12 months such as divorce, moving, starting a new job, and so on. The raw scores for each subscale are calculated and added together depending on the domain to which the subscales belong (i.e., child or parent) [1,17]. The total stress score combines those of the child and parent domains. The result of the PSI-4 provides the raw scores, percentile rank, and T-scores for each subscale within the child and parent domains, along with the total stress score. A T-score above the 90th percentile indicated “clinically significant” parenting stress. In this study, the percentile rank was used. The Korean version of the PSI-4 has been reported to have high internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficient, 0.94–0.97), test-retest reliability (0.95–0.97), and construct validity (0.96–0.97) [18]. The Total stress score was interchangeably termed as the total parenting stress in the current study. The questionnaire was conducted once at the first outpatient visit.

The Child Interactive Behavior Test (CIBT) was used to assess interactive engagement behaviors [19]. The CIBT is a 32-item inventory, which uses a 4-point Likert-type scale; it is used to measure interactive engagement behaviors in early childhood (between 1 and 6 years of age). This questionnaire was developed based on the pivotal behavior profile suggested by Mahoney and Wheeden [20]. The CIBT categorizes children’s interactive engagement behaviors into 4 factors: social interaction, initiative interaction, intentional interaction, and emotional interaction [19]. The social interaction factor consists of items that evaluate the degree of participation in interactive engagement with others to assess joint attention, joint activity, and social play among the pivotal behaviors [19]. The initiative interaction factor consists of items related to the degree of initiation, exploration, and feeling of confidence among the pivotal behaviors [19]. The intentional interaction factor consists of items that evaluate not only the communication of one’s needs or intentions but also the degree of listening to others and expressing one’s intention [19]. The intentional interaction factor consists of items related to the degree of vocalization, intentional communication, conversation among the pivotal behaviors [19]. The emotional interaction factor evaluates the understanding of others’ feelings and the formation of an attachment with parents [19]. The emotional interaction factor consists of items related to the degree of trust and empathy among the pivotal behaviors [19]. Studies have demonstrated that the CIBT has high internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficient, 0.89) and test-retest reliability (0.58) [19]. The comparative fit index and Tucker-Lewis index were 0.97 and 0.96, respectively, and the root mean square error of approximation was 0.06, suggesting good construct validity [19]. The CIBT results provide the raw scores, percentile rank, and T-scores for each subscale and the total score. The total CIBT score combines the 4 abovementioned behavior factors and has been used as a measure of overall interactive behaviors in this study. The questionnaire was conducted once at the first outpatient visit.

Data analysis was conducted using R ver. 4.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data are presented as numbers and percentages for qualitative variables and medians and interquartile ranges for quantitative variables. The Fisher exact test and Mann-Whitney U test were used to compare group differences. The eta-squared was calculated to evaluate the standardized effect sizes for differences between groups of subitems pertaining to the total PSI-4 and CIBT scores. An eta-squared value of ≥0.25 was defined as a large effect, as per Cohen [21]. Nonparametric regression analysis, specifically quantile regression analysis, was performed to identify the variables influencing the total score pertaining to parenting stress and interactive behavior of children. A causal mediation analysis was performed to analyze the mediating effect of the variables related to total parenting stress derived from the quantile regression analysis. The proposed causal mediation effect, as introduced by Imai et al. [22], aimed to identify the mediating influence of outcomes arising from covariates. They [22] newly defined the causal mediation effect by applying the counterfactual framework to the existing causal mediation model. The R package “mediation” was used to obtain the effect size [22]. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

During the study period, 71 children aged 12–43 months visited the outpatient clinic due to DDs. Among them, 22 children were excluded: 8 were diagnosed with ASD, and 11 did not undergo the recommended developmental assessment, including the Bayley-III. One child who had no DD as assessed using the Bayley-III was recruited to the normal control group. Thus, 51 patients were enrolled in this study in the delayed group. Among them, 34 were in the language delay group and 17 were in the global delay group. Twenty-four children with typical development were included in the control group.

The demographic characteristics of the children and their parents are shown in Table 1. The median age of the children in the delayed group was 31.0 months (25.0–35.5 months), and there were 42 boys in this group (82.4%). Except for one child, all questionnaires were completed by the children’s mothers. There were no differences in the children’s age, sex, age of parents, parental educational background, mother’s employment status, and marital status between the control and delayed groups. No difference was found in the demographics between the delay, language delay, and global delay groups. However, the BayleyIII composite score of the language and cognition domains was significantly lower in the global delay group than in the language delay group.

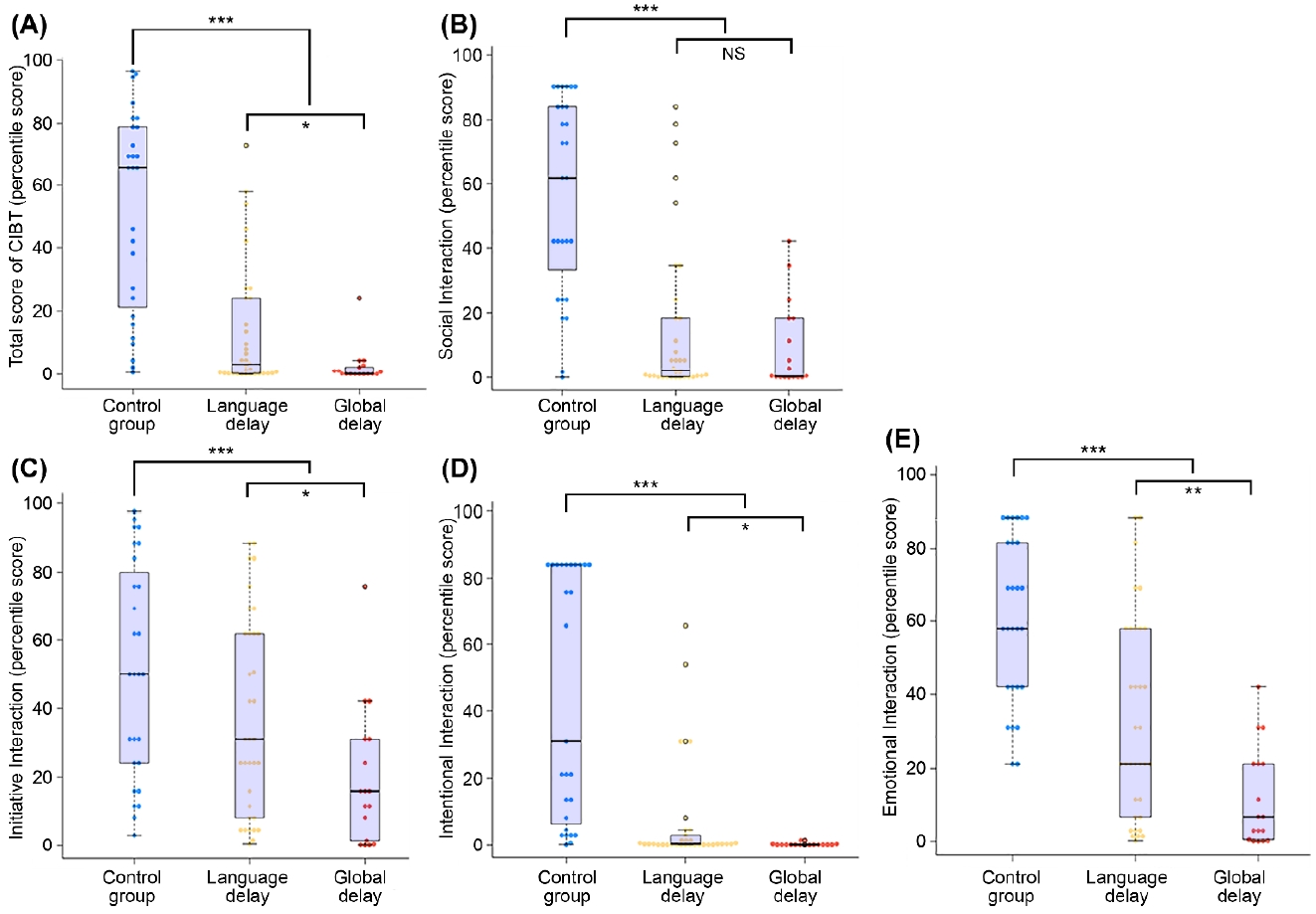

Parenting stress in the delayed group was higher than that in the control group on the PSI-4 total, child, and parent stress scales (P<0.01); however, the parenting stress was comparable between the groups for the PSI-4 life stress scale (P=0.29) (Fig. 1). No differences were found in the PSI-4 (total, child, parent, and life stress scale) scores between the language delay and global delay groups.

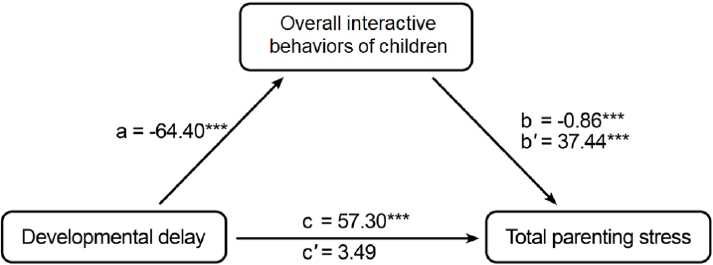

On the other hand, all scores related to interactive behaviors (those for the 4 subitems and the total score) were significantly lower in the delayed group than in the control group (P<0.01) (Fig. 2). Within the delayed group, the total score and those for all of the subitems, except for social interaction, were significantly lower in the global delay group than in the language delay group.

To evaluate the standardized effect size of each subitem of the questionnaires, eta-squared analysis was performed between the delay and control groups. All subitems of the child domain were significantly lower in the delayed group (Table 2). In the parent domain, competence, attachment, health, and depression were significantly lower in the delayed group. However, social isolation and role restriction were not different between the groups. The eta-squared value of acceptability (0.38) and competence (0.22) showed the largest effect size in the child and parent domains of the PSI-4, respectively. In the CIBT, social interaction (0.41) showed the largest effect size on the total score (Table 3).

The PSI-4 total stress scale and total CIBT score were considered as measures of total parenting stress and overall interactive engagement behaviors, respectively, and were used for analysis. In univariate analysis, the presence of delay, children’s age, mother’s education level, and overall interactive engagement behaviors were associated with total parenting stress. In multivariate analysis, the total CIBT score (adjusted coefficient -0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI], -1.17 to 0.67) and children’s age (adjusted coefficient, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.29–1.68) remained significant with respect to total parenting stress (Table 4).

In univariate analysis to identify factors affecting the overall interactive engagement behaviors, presence of delay, father’s education level, and the PSI-4 life stress scale were associated with the total CIBT score. In the multivariate analysis, the presence of delay was strongly related to the overall interactive engagement behaviors of the children (adjusted coefficient, -65.49; 95% CI, -70.48 to 44.45). Father’s education level was weakly related to the overall interactive engagement behaviors (adjusted coefficient, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.02–1.49) (Table 4).

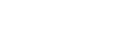

Fig. 3 shows that the total effect of “developmental delay” (independent variable) on total parenting stress (dependent variable) was significant (β=57.3, P<0.001). The regression coefficient between “developmental delay” and total parenting stress (β=-64.40, P<0.001) and that between the overall interactive engagement behaviors of children (mediator) and total parenting stress (β=-0.86, P<0.001) were also significant. The mediator significantly affected total parenting stress while controlling for “developmental delay” (average causal mediation effect, 37.44; P<0.001). On the other hand, the direct effect of “developmental delay” on total parenting stress (average direct effect, 3.49; P=0.44) was not significant when controlling for overall interactive engagement behaviors, which was the mediator. These results indicate that the effect of “developmental delay” on total parenting stress was fully mediated by the overall interactive engagement behaviors of the children.

Our results showed that total parenting stress and the overall interactive engagement behaviors of children were significantly lower in children with DDs (delayed group) than in those with typical development (control group). Total parenting stress was independently associated with the children’s overall interactive engagement behaviors and age but not with the presence of the DD. On the other hand, the presence of a DD had a strong negative effect on the overall interactive engagement behaviors of children. In the mediation analysis, the variable “developmental delay” did not directly affect total parenting stress. Instead, the overall interactive engagement behaviors functioned as a mediator between “developmental delay” and total parenting stress. Thus, DDs may exert a negative effect on the overall interactive engagement behaviors of children, which in turn contribute to an increase in total parenting stress. Our results showed that the children’s interactive engagement behaviors are critical factors in understanding and intervening in parenting stress associated with children with DDs.

The main finding of this study is in line with well-known results from previous studies, which showed that total parenting stress was higher with reference to children with DDs than with reference to those without DDs [4,23]. However, there are mixed results on whether parenting stress depends on the type or degree of developmental disability. Our data showed that parenting stresses were not different between the types of delay (language only vs. global delay); despite significantly lower language and cognitive abilities in the global delay group compared to the language delay group. Our results are similar with those of Vermeij et al. [24], who reported that parenting stress in children with language disorders did not differ by the type of language disorder (expressive vs. receptive and expressive problems). They found that language scores did not correlate with parenting stress [24]. On the other hand, Baker et al. [4] examined 3-year-old children (excluding those with ASD) and showed that parenting stress was related to the child’s cognitive functioning. However, Baker et al. also found that the problem behaviors of children with DDs had a stronger effect on parenting stress than their cognitive function [4,24]. All these findings suggest that high levels of parenting stress in children with DDs may not be explained by cognitive or linguistic abilities alone.

Current data suggest that the characteristics of interactive engagement behaviors of children with DDs have a significant impact their parents’ parenting stress. All of the interactive engagement behaviors evaluated by the CIBT were significantly lower in children with DDs than in those without DDs. In addition, mediation analysis clearly showed that elevated parenting stress in children with DDs was mediated by the lower interactive engagement behaviors of these children. The present results, as measured by the CIBT, are consistent with data from a previous study obtained through videotaped observations of interactive engagement behaviors during play situations [25,26]. Young children with developmental disabilities exhibited lower levels of interactive engagement than typically developing children [25,26]. However, there is very little information in the literature on the relationship between interactive engagement behaviors of children with DDs and parenting stress. The meta-analysis of studies comparing parenting stress in parents of children with and without ASD supports the main findings of this study [15]. The above mentioned meta-analysis suggests that parents of children with ASD experience more parenting stress than those of children with other disabilities or with typical development [15]. Lack of interactive engagement behaviors is a core symptom that distinguishes ASD from other disabilities.

The main strength of this study is that the behavioral characteristics related to parenting stress were interpreted as a decrease in the ability of interactive engagement rather than as problems. Most previous studies have labeled the behavioral characteristics of children with developmental disabilities that influence parenting stress as problematic behaviors using CBCL [4,7,9]. Among the 7 subscales of the CBCL, withdrawn and/or emotionally reactive have been suggested as explanatory variables for parenting stress in children with variable developmental disabilities, including ASD [27]. The withdrawn scale of the CBCL consists of items such as “Shows little affection towards people” and “Seems unresponsive to affection.” The emotionally reactive scale consists of “Sulks a lot” and “Upset by new people or situations.” These items are similar to the symptoms of ASD as well as the items in the CIBT, thus supporting this study. Among the 4 subscales of the CIBT, social interaction exerted the strongest effect on the difference in total CIBT scores between the 2 groups. The social interaction subscale includes questions related to the degree of participation in interactive play with others [19]. For example, “child is not paying attention to what others are saying,” “child plays alone while playing with toys,” and “child makes no effort or attempt to get other people’s attention” are included in this subitem of the CIBT. The social interaction items are designed to measure pivotal behaviors, including joint attention, joint activity, and social play [19]. Thus, the items in social interaction are consistent with the main characteristics of ASD. Our study showed that the social interaction scores were significantly lower in children with DDs, with a median percentile score of 1.1, which indicates a very low level of engagement behavior [19]. The present data underscore that children with DDs other than ASD also had poor interactive engagement behaviors. Our findings are in line with conventional wisdom, which states that social deficiencies lie at the core of overall developmental disabilities [28].

We investigated parenting stress using the PSI-4, which can be subdivided into the child, parent, and lifestyle domains. All subitems of the child domain were significantly higher in children with DDs than in those without delays. Among these child-related stresses, acceptability exerted the largest effect size. This means that the characteristics of children with DDs did not match their mothers’ expectations and accounted for a large part of their parenting stress. In terms of subscales of the parent domain, lower competence had the largest effect on total parenting stress. Interestingly, mothers in both the groups reported similar feelings with respect to social isolation and role restriction in our study. Our results are consistent with a standardization study of the Korean version of the PSI-4 [18]. Chung et al. [18] showed that all subscales of the child domain were higher in children with mental or developmental disorders than in typically developing children, with the greatest difference between the 2 groups being observed with reference to acceptability. They also reported that the scores pertaining to isolation and role restriction were similar between the 2 groups [18]. Among the subitems of the parent domain, depression had the largest effect on parenting stress [18]. In a South Korean standardization study of the initial version of the PSI conducted in 2008, the scores of all subscales of the parent and child domains were higher among parents of children with developmental disabilities than among those in the normal group [29]. The largest difference between the 2 groups was observed for demanding and acceptability in the child domain, and role restriction in the parent domain [29]. All these findings suggest that the stress of the child not matching the parents’ expectations, appears to consistently influence the parenting stress associated with children with developmental problems in Korea. Accepting a child’s developmental state and the specific characteristics has been considered as an important coping strategy for parenting stress associated with children with developmental problems [30]. Meanwhile, the parental characteristics related to parenting stress may change over time and with research subjects. An increase in social support for developmental disabilities such as childcare or activity assistance services in South Korea might gradually decrease the influence of social isolation and role restriction on total parenting stress. However, our data underscored that emotional and educational support to improve depression and competence related to parenting stress is still lacking.

Our study has some limitations. First, a single-center study with the small sample size reduces the power of the study. Second, the delayed group was evaluated using the Bayley-III as the diagnostic tool, while the control group was screened using the K-DST. Third, children aged 12–43 months were included because the study was designed as an age capable of Bayley-III and CIBT. This selection of age may have influenced the study results. Previous studies has shown that parenting stress may decrease with age as problem behaviors decrease [7,31]. Fourth, children with febrile seizures with typical development were selected as a control group because their development has been routinely evaluated using K-DST in practice. It is possible that the accompanying acute illness may have influenced the completion of the questionnaires. Sixth, our study was cross-sectional, and thus, a causal relationship between children’s interactive engagement behaviors and their parents’ parenting stress could not be deduced. Also, the PSI-4 life stress scale scores (including job loss, moving, and marital conflict) did not differ between the study and control groups. However, information on socioeconomic status and the presence or absence of siblings, which are known to influence parenting stress, were not included in the analysis.

In conclusion, the interactive engagement behaviors were reduced in non-ASD children with DDs, showing which had a significant effect on parenting stress. Our study highlights that social engagement abilities should be carefully evaluated in all children with DDs, not just in those with ASD. This study also shows that accepting a child’s developmental characteristics and increasing parental competence could be critical factors in reducing parenting stress. Clinicians responsible for assessing or treating children with DDs need to recognize these issues and may have a role as an intervener through parental education or counseling.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Jeongmee Kim, Korean Responsive Teaching Center, for her technical assistance for this study.

Fig. 1.

Parent Stress index (PSI)-4 results by study group. (A) Total parenting stress. (B) Parent domain stress. (C) Child domain stress. (D) Life stress domain. **P<0.01. ***P<0.001.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Child Interactive Behavior Test (CIBT) results among the study groups. (A) Total score of CIBT. (B) Social interaction. (C) Initiative interaction. (D) Intentional interaction. (E) Emotional interaction. NS, not significant. *P<0.05. **P<0.01. ***P<0.001.

Fig. 3.

Mediation effect of children’s overall interactive abilities on total parenting stress. Overall, the children’s interactive abilities fully mediated the relationship between developmental delay and total parenting stress. Path a, independent variable (developmental delay) to mediator (overall children’s interactive abilities); path b, mediator to dependent variable (total parenting stress); path b’, indirect effect of developmental delay on total parenting stress that goes through the mediator (average causal mediation effects); path c, total effect of developmental delay on total parenting stress; path c’, direct effect of developmental delay on total parenting stress with control for the mediator (average direct effects). *P<0.05. **P<0.01. ***P<0.001.

Table 1.

Basic patient demographic characteristics by study group

| Characteristic |

Delayed group (N=51) |

Control group (N=27) |

P valuea) |

P valueb) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=51) | Language delay (N=34) | Global delay (N=17) | |||||

| Age (mo) | 31.0 (25.0–35.5) | 31.0 (27.0–35.0) | 31.0 (24.0–38.0) | 31.0 (21.5–39.5) | 0.717 | 0.841 | |

| Male sex | 42 (82.4) | 29 (85.3) | 13 (76.5) | 16 (59.3) | 0.051 | 0.697 | |

| Mother’s age (yr) | 36.0 (33.0–39.0) | 35.5 (33.0–38.0) | 37.0 (32.0–41.0) | 34.0 (32.0–37.0) | 0.139 | 0.343 | |

| Father’s age (yr) | 37.0 (35.0–39.0) | 38.0 (36.0–42.0) | 38.0 (36.0–40.5) | 41.0 (35.0–43.0) | 0.122 | 0.248 | |

| Mother’s education level | 0.257 | 0.476 | |||||

| <College | 10 (19.6) | 5 (14.7) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (7.4) | |||

| ≥College | 38 (74.5) | 26 (76.4) | 12 (70.6) | 24 (88.8) | |||

| Missing data | 3 (5.8) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | |||

| Father’s education level | 0.284 | 1.000 | |||||

| <College | 12 (19.6) | 8 (23.5) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (11.1) | |||

| ≥College | 36 (70.5) | 24 (70.5) | 12 (70.5) | 23 (85.1) | |||

| Missing data | 3 (5.8) | 3 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | |||

| Maternal employment status | 0.294 | 0.970 | |||||

| Yes | 21 (43.8) | 13 (41.9) | 8 (47.1) | 16 (59.3) | |||

| Marital status | 0.556 | 0.697 | |||||

| Divorced/single parent | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | 2 (7.7) | |||

| Composite scores of Bayely-III | |||||||

| Language | 65.0 (59.0–74.0) | 71.0 (65.0–77.0) | 56.0 (50.0–62.0) | N/A | <0.001 | ||

| Cognition | 85.0 (80.0–90.0) | 90.0 (85.0–95.0) | 70.0 (60.0–80.0) | N/A | <0.001 | ||

Table 2.

Standardized effect sizes of intergroup differences in Parenting Stress Index, Fourth Edition subgroup values

Table 3.

Standardized effect sizes of intergroup differences in CIBT subitems

Table 4.

Quantile regression analysis of variables influencing overall interactive engagement behaviors and total parenting stress

| Variable |

Overall interactive engagement behaviors |

Total parenting stress |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| Group | |||||

| Control | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | ||

| Delay | -64.40 (-71.79 to -39.80) | -65.49 (-70.48 to -44.45)*** | 57.30 (38.00 to 63.80) | 1.96 (-18.9 to 21.72) | |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |||

| Female | 19.70 (-4.19 to 62.05) | -13.20 (-38.11 to 20.08) | |||

| Children’s age | 0.09 (-0.69 to 0.94) | 0.94 (0.41 to 2.19) | 0.73 (0.29 to 1.68)* | ||

| Mother’s age | -0.54 (-1.45 to 0.62) | -1.10 (-1.31 to 1.08) | |||

| Father’s age | -0.85 (-2.49 to 0.19) | -1.31 (-2.45 to 1.05) | |||

| Mather’s education levels | |||||

| <College | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |||

| ≥College | 6.10 (-1.41 to 14.59) | -20.40 (-32.87 to -8.56) | -4.93 (-8.45 to 14.17) | ||

| Father’s education levels | |||||

| <College | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |||

| ≥College | 13.60 (4.11 to 26.95) | 0.40 (0.02 to 1.49)* | -17.10 (-31.65 to 10.64) | ||

| Maternal employment | |||||

| No | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 2.20 (-1.80 to 21.98) | 5.70 (-20.17 to 25.75) | |||

| Single parent | |||||

| No | 0 (reference) | 0 (reference) | |||

| Yes | 68.10 (-6.41 to 89.03) | -58.90 (-60.82 to 9.20) | |||

| Living stress | -0.21 (-0.33 to -0.01) | -0.04 (-0.09 to 0.00)* | 0.41 (-0.30 to 0.78) | ||

| Total score of CIBT | -0.86 (-1.01 to -0.69) | -0.85 (-1.17 to -0.67)*** | |||

References

1. Abidin R. Parenting stress index-fourth edition (PSI-4). Lutz (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources, 2012.

2. Barroso NE, Mendez L, Graziano PA, Bagner DM. Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: a systematic review & meta-analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2018;46:449–61.

3. Dietz KR, Lavigne JV, Arend R, Rosenbaum D. Relation between intelligence and psychopathology among preschoolers. J Clin Child Psychol 1997;26:99–107.

4. Baker BL, Blacher J, Crnic KA, Edelbrock C. Behavior problems and parenting stress in families of three-year-old children with and without developmental delays. Am J Ment Retard 2002;107:433–44.

5. Spratt EG, Saylor CF, Macias MM. Assessing parenting stress in multiple samples of children with special needs (CSN). Fam Syst Health 2007;25:435–49.

6. Belsky J, Woodworth S, Crnic K. Trouble in the second year: three questions about family interaction. Child Dev 1996;67:556–78.

7. Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: a transactional relationship across time. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil 2012;117:48–66.

8. Rothbaum F, Weisz JR. Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 1994;116:55–74.

9. Baker ASL. Preschool children with and without developmental delay: behaviour problems, parents optimism and well-being. J Intellect Disabil Res 2005;49(Pt 8): 575–90.

10. Mahoney G, Kim JM, Lin C. Pivotal behavior model of developmental learning. Infants Young Child 2007;20:311–25.

11. Feldman R. Bio-behavioral synchrony: a model for integrating biological and microsocial behavioral processes in the study of parenting. Parent Sci Pract 2012;12:154–64.

12. Farroni T, Johnson MH, Menon E, Zulian L, Faraguna D, Csibra G. Newborns' preference for face-relevant stimuli: effects of contrast polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:17245–50.

13. Koegel LK, Koegel RL, Carter CM. Pivotal responses and the natural language teaching paradigm. Semin Speech Lang 1998;19:355. –71. quiz 372; 424.

14. Merrell KW, Hollan ML. Social-emotional behavior of preschool-age children with and without developmental delays. Res Dev Disabil 1997;18:393–405.

15. Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43:629–42.

16. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

17. Johnson AO. Test review: parenting stress index, fourth edition (PSI-4). J Psychoeduc Asses 2015;33:698–702.

18. Chung K, Lee Si, Lee C. Standardization study for the korean version of parenting stress index fourth edition (K-PSI-4). Kor J Psychol Gen 2019;38:247–73.

19. Kim JM. The study on the development and validation of child interactive behavior test (CIBT) for early childhood pivotal behaviors. Korean J Early Child Educ 2019;19:245–64.

20. Mahoney G, Wheeden CA. The effect of teacher style on interactive engagement of preschool-aged children with special learning needs. Early Child Res Q 1999;14:51–68.

22. Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 2010;15:309–34.

23. Baker BL, McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Crnic K, Edelbrock C, Low C. Preschool children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. J Intellect Disabil Res 2003;47:217–30.

24. Vermeij BAM, Wiefferink CH, Knoors H, Scholte R. Association of language, behavior, and parental stress in young children with a language disorder. Res Dev Disabil 2019;85:143–53.

25. Kim JM, Mahoney G. The effects of mother's style of interaction on children's engagement. Topics Early Child Spec Educ 2004;24:31–8.

26. Colla S, Van Leeuwen K, Vlaskamp C, Ceulemans E, Hoppenbrouwers K, Desoete A, et al. Exploring parental behavior and child interactive engagement: a study on children with a significant cognitive and motor developmental delay. Res Dev Disabil 2017;64:131–42.

27. Tervo RC. Developmental and behavior problems predict parenting stress in young children with global delay. J Child Neurol 2012;27:291–6.

28. Kopp CB, Baker BL, Brown KW. Social skills and their correlates: preschoolers with developmental delays. Am J Ment Retard 1992;96:357–66.

29. Chung KM, Lee KS, Park JA, Kim HJ. Standardization study for the korean version of parenting stress index (K-PSI). Kor J Clin Psychol 2008;27:689–707.

30. Kowalkowski JD. The impact of a group-based acceptance and commitment therapy intervention on parents of children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder [dissertation] Ypsilanti (MI), Eastern Michigan University. 2012.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link PubMed

PubMed Download Citation

Download Citation